Outcomes of Enhanced Counseling Services Provided to Adults Through Project Liberty

Disasters, such as the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, have detrimental mental health consequences, including acute stress reactions, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ( 1 , 2 ), major depressive disorder ( 3 ), and complicated grief ( 4 , 5 ). The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funds disaster relief programs, including crisis counseling that targets mental health problems. FEMA stipulates that all services are free, and service recipients remain anonymous. Using FEMA funding, the New York State Office of Mental Health (NYOMH) implemented Project Liberty to provide crisis counseling and public education services for residents of New York City and surrounding counties. Individual crisis counseling services were provided to 687,848 people by a large network of trained mental health professionals and paraprofessionals, with another approximately 550,000 receiving public education ( 6 ). Initial implementation of Project Liberty was driven by pressing service needs of individuals in a highly stressed environment. Project Liberty's primary goal was to facilitate return to predisaster functioning among as many people as possible.

More than a year after the attacks, reports from Project Liberty providers indicated clearly that additional services were needed for some individuals still struggling with serious disaster-related problems. This judgment was consistent with results of community surveys undertaken to characterize mental health reactions over time ( 7 , 8 ). In August 2003 FEMA approved a first-time expansion to include longer-term "enhanced services" counseling for individuals whose disaster-related mental health needs went beyond what could be met through brief crisis counseling. Separate screening tools and interventions were developed for children and adults.

NYOMH contracted with the National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the University of Pittsburgh Bereavement and Grief Program to plan the enhanced services program for adults, including developing a screening tool, training crisis counselors to make referrals, and developing manuals for cognitive-behavioral and grief interventions to target an array of disaster-related problems. The Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview ( 9 ) was modified, with permission of the authors, into an 11-item questionnaire that rated core symptoms of PTSD (intrusion, avoidance, numbing, and arousal), stress vulnerability, and functional impairment using 5-point scales (from 1, not at all, to 5, very much). Counselors were directed to complete this assessment during the second or third counseling session. Recipients who had begun receiving crisis counseling before the implementation of enhanced services in June 2003 were also assessed even if they had participated in more than three counseling sessions. Respondents who answered "quite a bit" or "very much" to at least three items were offered a referral to enhanced services ( 10 ).

The cognitive-behavioral intervention included techniques for recognizing postdisaster distress; developing skills to cope with anxiety, depression, and other symptoms; and teaching cognitive reframing. The Bereavement and Grief Program developed a Grief Intervention Guidebook that included information about natural grieving processes and traumatic grief symptoms. A two-track approach to working with traumatic grief, based on the Stroebe and Schut coping model ( 11 ), included strategies for dealing with loss and for reengaging in satisfying life activities without loved ones who died. Techniques for working with problem emotions (guilt and anger) were included. Both interventions were supported by manuals, included homework materials, and were designed to be ten to 12 sessions in length. NYOMH sponsored training programs for enhanced services clinicians on both interventions. (Manuals developed by these groups are available on request.)

Project Liberty administrators considered program evaluation a priority. As a requirement for reimbursement, all providers completed service encounter logs that provided data related to where, how, and to whom services were provided and on further need for services. These logs were analyzed to provide information regarding the scope and outcome of Project Liberty services ( 12 , 13 ). In addition, Project Liberty contracted with the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Division of Health Services Research to undertake more detailed evaluations. Anonymous, brief self-report questionnaires and confidential structured telephone interviews were used to expand upon log data. Telephone interviews were conducted with crisis counseling recipients about 18 months after the attacks and with enhanced services recipients about 24 months after the attacks.

Screening of crisis counseling recipients began at the end of June 2003, with enrollment in enhanced services beginning shortly thereafter. New enrollees continued to be added until mid-December 2003, when the program stopped taking new clients. By the beginning of October 2003, a total of 128 adults had enrolled in enhanced services. Distribution of permission-to-contact forms, the first step in obtaining permission to interview a service recipient for this evaluation, began in October 2003 and continued until mid-December. From October to December 2003 an additional 96 adults began receiving enhanced services.

An enhanced services program for the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) began in the fall of 2003 and continued to operate throughout 2004, a full year after the community-based enhanced services program ended. The screening tool and enhanced services encounter log used by the community-based programs were implemented with the FDNY in January 2004, with evaluation commencing in February 2004.

This report examines interview data to assess the relative impairment of individuals who received enhanced services compared with those who received only crisis counseling and to determine whether the provision of additional services resulted in better outcomes for enhanced services recipients.

Methods

Study site selection and staff training

For enhanced services, NYOMH identified 17 agencies that documented their capacity to provide brief, evidence-based, trauma-focused interventions using licensed mental health professionals with experience in treating PTSD and depression. Eight sites submitting a high volume of service encounter logs for individual crisis counseling, which were by design different from one another geographically, culturally, and ethnically, participated in the crisis counseling evaluation. Evaluators conducted staff training at each site and monitored study progress. For both evaluations, counselors distributed forms in English or Spanish requesting permission for independent evaluators to conduct telephone interviews with service recipients, for which respondents would receive $20.

For crisis counseling, distribution of forms occurred at the eight sites during the winter of 2003, with telephone interviews conducted from February to June 2003 (the median completion date for crisis counseling interviews was in March 2003). Of the 214 crisis counseling service recipients who agreed to be contacted, 153 (71 percent) completed the telephone interview, and the remaining 61 (29 percent) did not participate for various reasons ( 14 ). Initial telephone interviews of recipients of enhanced services were conducted between October 2003 and May 2004 (the median completion date was in December 2003). Of the 119 enhanced services recipients who agreed to be interviewed, interviewers contacted 102 (86 percent). Of the 102 contacted, 93 (91 percent) completed the first telephone interview and 76 (75 percent) completed a second interview that occurred a mean±SD of 48±19 days after the first (median=40.5 days).

Study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the NYOMH institutional review boards.

Telephone interview

Structured interviews queried participants about their experiences during the attacks, reasons for contacting Project Liberty, background demographic characteristics, extent of symptomatic and functional impairment, and interventions received. Questions were structured to reflect content that had been used in prior surveys ( 15 , 16 ) and were worded at a sixth-grade reading level.

Depression and PTSD symptoms. Respondents reported whether they had experienced for two weeks or longer during the previous month symptoms consistent with depression or PTSD. Our primary measure was the number of reported symptoms, scored as present (1) or absent (0). These symptom lists were drawn from existing measures and subsequently mapped onto DSM-IV-TR criteria for current major depressive disorder (ten symptoms) and PTSD (17 symptoms) according to algorithms developed by Galea and colleagues ( 15 , 16 ).

Meeting criteria suggestive of a full major depressive disorder diagnosis was defined as the presence of at least one of two cardinal depression symptoms (feeling depressed or losing interest in pleasurable activities) and at least four of eight additional depressive symptoms (feeling worthless or guilty, for example). Subthreshold major depressive disorder was defined as one cardinal symptom and at least one other depressive symptom.

Meeting criteria suggestive of a full PTSD diagnosis was defined as the presence of at least one of four persistent reexperiencing symptoms (such as flashbacks), at least three of seven avoidance symptoms (such as feeling numb), and at least two of five arousal items (such as trouble concentrating). Subthreshold criteria for PTSD were defined as at least one persistent reexperiencing item and either three avoidance or two arousal items.

Complicated grief. Interviewers asked respondents whether they personally knew anyone who had died as a result of the attacks. If respondents indicated that they had lost someone, interviewers asked them to respond to five questions to assess presence and extent of complicated grief: How much are you having trouble accepting the death of [deceased]? How much does your grief still interfere with your life? How often are you having images or thoughts of your [insert relationship of deceased]? Are there things you used to do when [deceased] was alive that you don't feel comfortable doing anymore, that you avoid? and How much are you feeling cut off or distant from other people since [deceased] died? Each item was rated on a 3-point scale of 0, not at all; 1, somewhat; and 2, a lot, which yielded a 0-10 range. Examination of this questionnaire indicated it had good internal consistency (Cronbach's α =.82). A score of 8 or more indicated probable complicated grief, and a score between 5 and less than 8 indicated probable subthreshold complicated grief ( 14 ).

Daily functioning. Respondents rated their current functioning using 4-point Likert scales (1, poor; 2, fair; 3, good; and 4, excellent) in five domains: job or school, maintaining relationships with family and friends, handling daily household activities, ability to take care of physical health, and staying involved in community activities.

Statistical analyses

Reported symptoms did not follow normal distributions, which necessitated using Mann-Whitney U tests to examine differences between the groups who received enhanced services compared with crisis counseling. We then evaluated changes in the enhanced services sample from the first to the second interview, in terms of symptoms, probable diagnostic category, and daily functioning, by applying Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests, McNemar tests, and Friedman's tests ( 17 ), respectively. Finally, we computed hierarchical regressions to determine predictors of change in the number of PTSD and depression symptoms, with blocks of variables entered stepwise as demographic features (age, gender, and race or ethnicity), risk factors (for example, being injured in the attacks), number of enhanced services sessions received, and persistent difficulty with accepting the death of a loved one.

Results

Comparisons between counseling groups

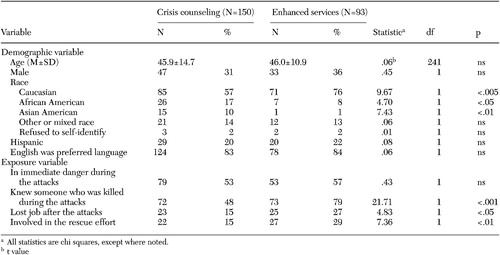

The crisis counseling and enhanced services samples did not differ in age or in gender composition. Enhanced services recipients were significantly more likely to be Caucasian and less likely to be African American or Asian American ( Table 1 ). There was no significant difference in respondents' assessment of being in immediate danger during the World Trade Center attacks, but significantly greater proportions of enhanced services recipients reported knowing someone who died as a result of the attacks, having been involved in rescue efforts, or having lost their job because of the attacks.

|

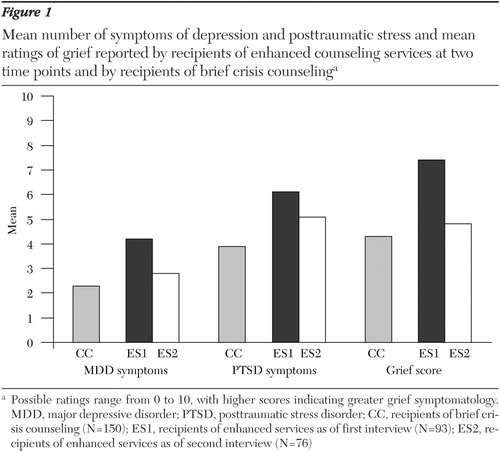

Figure 1 shows the mean number of depression and PTSD symptoms and mean complicated grief score of crisis counseling recipients during their only interview and enhanced services recipients at their first and second interviews. Compared with the crisis counseling sample, the enhanced services recipients at the time of the first interview reported significantly more symptoms of depression (enhanced services, mean±SD=4.2±3.2; crisis counseling, 2.3±2.9; z=-4.81, p<.001) and PTSD (enhanced services, 6.1±5.0; crisis counseling, 3.9±4.3; z=-3.28, p<.005) and more intense grief (enhanced services, 7.4±2.1; crisis counseling, 4.3±3.1; z=-4.10, p<.001).

a Possible ratings range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater grief symptomatology. MDD, major depressive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; CC, recipients of brief crisis counseling (N=150); ES1, recipients of enhanced services as of first interview (N=93); ES2, recipients of enhanced services as of second interview (N=76)

The enhanced services recipients were significantly more likely to meet criteria listed previously as suggestive of diagnoses of major depressive disorder ( χ2 =17.79, df=1, p<.001) and PTSD ( χ2 =7.41, df=1, p<.01). For the enhanced services sample, 39 (42 percent) and an additional 15 (16 percent) recipients met full and subthreshold criteria, respectively, suggestive of major depressive disorder; 36 (39 percent) and eight (9 percent) recipients met full and subthreshold criteria, respectively, suggestive of PTSD. Of the 73 enhanced services respondents who reported knowing personally someone who had been killed, 19 (26 percent) met criteria for probable complicated grief and an additional nine (12 percent) met criteria for probable subthreshold complicated grief when interviewed 24 to 30 months after the attacks.

Enhanced services recipients at the first interview also were significantly more impaired than crisis counseling respondents in their daily functioning ( Figure 2 ; job and school: crisis counseling, 34 percent; enhanced services first interview, 53 percent; z=-2.21, p<.05; personal relationships: crisis counseling, 25 percent; enhanced services first interview, 44 percent; z=-3.10, p<.005; household activities: crisis counseling, 35 percent; enhanced services first interview, 52 percent; z=-2.14, p<.05; maintaining physical health: crisis counseling, 35 percent; enhanced services first interview, 55 percent; z=-2.62, p<.01; community involvement: crisis counseling, 35 percent; enhanced services first interview, 59 percent; z=-3.42, p<.005).

a CC, recipients of brief crisis counseling (N=150); ES1, recipients of enhanced services as of first interview (N=93); ES2, recipients of enhanced services as of second interview (N=76)

Changes over time from first to follow-up interviews

Enhanced services recipients reported a significant reduction in number of depressive symptoms from the first to the second interview (second interview, mean=2.8±2.8; first interview, mean=4.2±3.2; z=-2.82, p<.01), significantly reduced intensity of grief (second interview, mean=4.8±3.9; first interview, mean=7.4±2.1; z=-3.06, p<.005), and significantly improved daily functioning in three of five life domains (job and school, χ2 =8.76, df=1, p=.003; personal relationships, χ2 =6.08, df=1, p=.014; and household activities, χ2 =15.16, df=1, p=.001).

Respondents were less likely to meet criteria suggestive of major depressive disorder at follow-up (51 percent at baseline compared with 37 percent at follow-up; McNemar test, p=.06). The number of PTSD symptoms was also notably reduced (second interview, mean=5.1±4.7; first interview, mean=6.1±5.0; z=-1.82, p=.07), and the reported ability to manage physical health was improved ( χ2 =3.43, df=1, p=.06). These changes for enhanced services recipients made their profiles at follow-up similar to the level of functioning reported by crisis counseling recipients about one year earlier.

Predictors of improvement in major depression and PTSD

The final hierarchical regression model for predicting improvement in depression symptoms yielded an adjusted R 2 of .158 (F=1.50, df=1 and 25, p=.12). The final model for predictors of improvement in PTSD symptoms yielded an adjusted R 2 of .180 (F=1.51, df=1 and 25, p=.09). Given that neither model was statistically significant and the coefficient of determination was relatively small, we concluded that symptom reduction could not be predicted from demographic, risk, or service use variables.

Discussion

This investigation has several limitations, and findings should be considered preliminary. Participating crisis counseling sites were not selected at random. They were, however, selected on the basis of high-encounter log volume and to reflect accurately the geographic, cultural, and ethnic heterogeneity of the populations that Project Liberty served. The two enhanced services interviews do not represent a true temporal comparison because there was variation in the timing of initial interviews and between-interview intervals for different enhanced services participants. Nevertheless, given that this study was the first systematic effort to evaluate the effectiveness of disaster mental health services, we found a number of provocative results.

Despite the resilience in returning to normal that was shown by a vast majority of New York City residents after the attacks on the World Trade Center ( 7 , 16 ), and documented assistance in regaining functioning by roughly two-thirds ( 18 ) of individuals who received Project Liberty crisis services, there was still a substantial minority who reported experiencing serious symptomatology for six ( 8 ) to 12 months ( 7 ) afterward ( 13 ).

Our findings suggest that the screening tool used by Project Liberty crisis counselors was accurate in identifying individuals who needed additional treatment. Enhanced services recipients were more likely than crisis counseling recipients to have exposure risk factors reported in earlier surveys and found to be associated with prolonged depression and PTSD after the attacks on the World Trade Center ( 7 , 14 ). Independent telephone assessments also indicated that, compared with crisis counseling recipients, those who also received enhanced services reported experiencing significantly more symptoms of depression, PTSD, and grief and significantly greater daily impairment. Demographic and exposure characteristics of enhanced services recipients corresponded to those of individuals less likely to regain preattack functioning after crisis counseling ( 18 ).

Of note, the enhanced services recipients who were interviewed a second time reported reductions in symptoms related to depression and grief and significant improvement in school, work, and household functioning, and maintaining relationships. Provision of enhanced services appears to have made a difference for individuals who still manifested substantial impairment more than a year after the attacks on the World Trade Center. However, interviews regarding enhanced services were conducted approximately nine months after interviews about crisis counseling. At the time, the crisis counseling recipients may have had fewer or less severe symptoms than earlier crisis counseling recipients. Also, improvements shown by enhanced services recipients may have been a product of regression to the mean or time artifacts. However, the fact that we found little difference in rates of severe symptoms in late compared with early crisis counseling recipients ( 13 ) makes this possibility less likely.

Conclusions

More than two years after the attacks on the World Trade Center, Project Liberty counselors could identify crisis counseling recipients who needed more intensive counseling and transition them to an enhanced program where they were offered ten to 12 additional counseling sessions by licensed clinicians with specialized training. Compared with crisis counseling recipients, users of enhanced services were more likely to have been involved directly in World Trade Center rescue efforts, to have personally known someone who died, or to have lost their jobs as a result of the attacks. Receiving a brief manual-based intervention from a trained mental health professional was associated with improvements in depression, complicated grief, and daily functioning at work, school, and home reported at follow-up interviews conducted approximately seven weeks after the intervention. The self-reported improvements among recipients of enhanced services suggest that meaningful improvements in functioning and symptoms may be associated with the receipt of enhanced services.

Acknowledgments

This evaluation was funded by grant FEMA-1391-DR-NY (titled "Project Liberty: Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program") to New York State from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. The Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration administered the grant. Additional funding was provided by grants MH-60783, MH-30915, and MH-52247 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the University of Pittsburgh. The authors express their appreciation to George Allen, Ph.D., and Nancy H. Covell, Ph.D., and to Schulman, Ronca, and Bucuvalas, Inc.

1. Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, et al: Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71:692-700, 2003Google Scholar

2. O'Donnell ML, Creamer M, Bryant RA, et al: Posttraumatic disorders following injury: an empirical and methodological review. Clinical Psychology Review 23:587-604, 2003Google Scholar

3. Brown, ES, Fulton MK, Wilkeson A, et al: The psychiatric sequelae of civilian trauma. Comprehensive Psychiatry 4:19-23, 2000Google Scholar

4. Lichtenthal WG, Cruess DG, Prigerson HG: A case for establishing complicated grief as a distinct mental disorder in DSM-V. Clinical Psychology Review 24:637-662, 2004Google Scholar

5. Pfefferbaum B, Call JA, Lensgraf SJ, et al: Traumatic grief in a convenience sample of victims seeking support services after a terrorist incident. Annals of Clinical psychiatry 13:19-24, 2001Google Scholar

6. Felton C: Project Liberty: a public health response to New Yorkers' mental health needs arising from the World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 79:429-433, 2002Google Scholar

7. Boscarino JA, Adams RE, Figley CR: Mental health service use 1-year after the World Trade Center disaster: implications for mental health care. General Hospital Psychiatry 26:346-358, 2004Google Scholar

8. DeLisi LE, Maurizio A, Yost M, et al: A survey of New Yorkers after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:780-783, 2003Google Scholar

9. Connor K, Davidson J: SPRINT: a brief global assessment of post-traumatic stress disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 16:279-284, 2001Google Scholar

10. Norris FH, Donahue SA, Felton CJ, et al: A psychometric analysis of Project Liberty's Adult Enhanced Services Referral Tool. Psychiatric Services 57:1328-1334, 2006Google Scholar

11. Stroebe M, Schut H: The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Studies 23:197-224, 1999Google Scholar

12. Donahue SA, Covell NH, Foster MJ, et al: Demographic characteristics of individuals who received Project Liberty crisis counseling services. Psychiatric Services 57:1261-1267, 2006Google Scholar

13. Jackson CT, Allen G, Essock SM, et al: Clusters of event reactions among recipients of Project Liberty mental health counseling. Psychiatric Services 57:1271-1276, 2006Google Scholar

14. Shear KM, Jackson CT, Essock SM, et al: Screening for complicated grief among Project Liberty service recipients 18 months after September 11, 2001. Psychiatric Services 57:1291-1297, 2006Google Scholar

15. Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 346:982-987, 2002Google Scholar

16. Galea S, Vlahov D, Resnick H, et al: Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology 158:514-524, 2003Google Scholar

17. Pett MA: Nonparametric Statistics in Health Care Research: Statistics for Small Samples and Unusual Distributions. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1997Google Scholar

18. Jackson CT, Covell NH, Shear KM, et al: The road back: predictors of regaining preattack functioning among Project Liberty clients. Psychiatric Services 57:1283-1290, 2006Google Scholar