PRISM-E: Comparison of Integrated Care and Enhanced Specialty Referral Models in Depression Outcomes

Between 5 and 10 percent of older primary care patients meet diagnostic criteria for major depression or dysthymia, and at least 5 to 16 percent experience subsyndromal symptoms of depression ( 1 , 2 ). Depression among older adults is associated with compromised functioning, suicide, poor health outcomes, and increased health care costs ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). A majority of older adults seek or receive treatment for depression in primary care settings ( 7 ). However, the many demands of primary care present substantial challenges to effective detection and treatment of mental disorders ( 7 , 8 , 9 ). Compared with younger adults, older primary care patients are at increased risk of inadequate treatment of depression ( 10 ) and are less likely to be referred to specialty mental health clinics ( 11 ).

A variety of approaches have been evaluated. Standard approaches for improving outcomes for the general population of primary care patients with depression (for example, physician education, routine depression screening, and dissemination of treatment guidelines) have had a minimal effect on depression outcomes ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). However, collaborative care models that integrate mental health services within primary care by using an on-site mental health specialist and treatment algorithms have demonstrated improved outcomes for major depression compared with usual care ( 15 , 16 , 17 ).

Two recent studies—the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial study (PROSPECT) and the Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment study (IMPACT) ( 18 , 19 )—compared the effectiveness of integrated treatment of major depression with the effectiveness of usual care for older primary care patients, reporting better outcomes for collaborative care that used on-site mental health specialists and standardized treatment algorithms for brief psychotherapy and medication management compared with usual care. The purpose of the Primary Care Research in Substance Abuse and Mental Health for the Elderly (PRISM-E) study was to develop two methods of organizing mental health care and to implement these models in diverse primary care settings, while maintaining existing standards of treatment. The research goal was to determine whether enhancements to, and standardization of, the care models improved access to treatment, outcome, and costs for patients, without mandating providers' conversion to standardized depression treatment algorithms or interventions ( 20 ). In a first report of PRISM-E study results, we found superior engagement rates for older primary care patients with depression in integrated care compared with the engagement rates for those who received enhanced referral to specialty care ( 21 ).

The study reported here compared the clinical outcomes for older primary care patients with depression who received integrated mental health services with the outcomes for those receiving enhanced referral to specialty mental health clinics by addressing two questions. First, what are the comparative outcomes for treatment of depression among older primary care patients in integrated mental health services compared with enhanced referral to specialty mental health clinics? Second, do outcomes differ between these two models of care with respect to the type of depression?

Methods

The PRISM-E Study is a multisite, randomized trial comparing service use, outcomes, and costs in integrated and enhanced referral models of mental health care for older persons with depression, anxiety, or at-risk alcohol consumption. The study was conducted from March 2000 to March 2002. The protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at each of the ten sites at which participants were treated as well as at the coordinating center. In the integrated care model, patients received mental health services, substance abuse services, or both in the primary care clinic from a mental health provider. The enhanced specialty referral model provided mental health services, substance abuse services, or both in a specialty setting that is physically separate and designated as a mental health or substance abuse clinic. See Levkoff and colleagues ( 20 ) for a detailed overview of study methods.

Sample

A total of 24,930 elderly primary care patients were screened for mental health symptoms with the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) ( 22 ). Possible scores on the GHQ range from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater levels of depression and anxiety symptoms. A total of 542 patients were excluded because of cognitive impairment, 249 were excluded because of incomplete data, and 311 women from Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) sites were excluded because, per study protocol, only men were studied at VA sites. A total of 2,608 potential participants elected not to proceed to a baseline assessment interview, and 617 were excluded because they were already in mental health or substance abuse treatment.

Compared with patients who consented to participate in the study's baseline assessment, those who refused were more likely to be male (2,899 patients, or 89.9 percent of males, compared with 2,394 patients, or 75 percent of females; χ 2 =105.8, df=1, p<.001); to be Caucasian (2,345 patients, or 72 percent of Caucasians, compared with 1,923 patients, or 60 percent of other groups; χ 2 =104.9, df=1, p<.001); to have a lower mean GHQ score (mean±SD score of 3.5±3.1 compared with 4.3±3.1; p<.001), indicating less severe distress; and to report more drinks consumed per week (mean of 6.0±11.5 drinks compared with 5.1±9.8 drinks; z=3.27, p<.001).

The 3,205 patients who provided written informed consent completed the baseline assessment for depression, anxiety, and at-risk drinking target conditions to determine eligibility for entry into the PRISM-E study. A total of 992 failed to meet criteria for a target diagnosis, 118 were ineligible for the study because of incomplete data, and 73 were ineligible because they had hypomania or psychosis. The final study sample consisted of 2,022 study participants, including 1,531 who met criteria on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) for depressive disorders of interest, with or without comorbid anxiety. At the six-month follow-up, 79 percent of the participants who had been randomly assigned to the integrated care model (599 of 758 patients) and 80 percent who had been randomly assigned to the enhanced referral model (621 of 773 patients) had completed assessments in the two types of care models. Eighty-nine percent of all patients with a six-month assessment also had a three-month assessment (1,088 of 1,220 patients).

At eight of ten sites, patients were randomly assigned in equal numbers to the integrated care or enhanced specialty referral models by a permuted-blocks design. Blocks were stratified by site, major diagnostic category, and age group. Two VA sites had already allocated patients to integrated care and enhanced specialty referral clinics on the basis of Social Security number in an unbiased manner.

Study intervention

integrated care models met the following criteria for site eligibility: mental health and substance abuse services co-located in primary care (including assessment, care planning, counseling, case management, psychotherapy, and pharmacological treatment), with no distinction in terms of signage of mental health or substance abuse services; mental health and substance abuse services provided by licensed mental health providers (that is, social workers, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, psychiatrists, and master's-level counselors); verbal or written communication about the evaluation and treatment plan between the mental health or substance abuse clinician and the primary care provider; and an appointment with the mental health or substance abuse provider was available within two to four weeks after the primary care provider visit.

The criteria for the enhanced specialty referral model included the following elements: referral of identified patients to an available appointment with the specialty mental health care clinic within two to four weeks of the primary care provider appointment, mental health or substance abuse evaluation and treatment occurred in a physically separate location by licensed mental health professionals, coordinated follow-up contacts if the patient missed the first scheduled visit, ensured transportation, and availability of urgent or emergency consults.

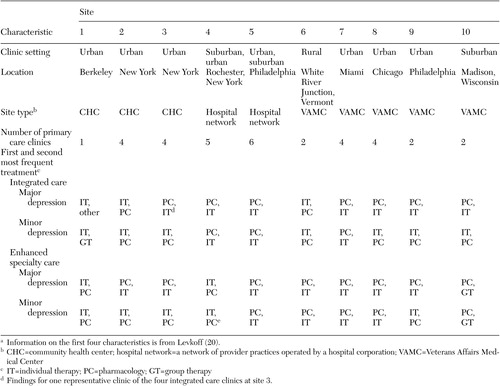

Because our real-world implementation approach allowed sites some flexibility beyond the above-delineated criteria for each model, we describe in Table 1 the clinic setting, location, and type, as well as the types of treatments most likely employed for different types of depression in each model at each site, as reported in process evaluations. Five of the ten sites were clinics in VA medical centers, three were community health clinics, and two were parts of networks operated by hospital corporations. During site visits carried out by staff of the coordinating center, it was determined that a majority of sites used pharmacotherapy for the treatment of major depression and individual therapy for the treatment of minor depression in both integrated care and enhanced specialty referral sites ( Table 1 ).

|

a Information on the first four characteristics is from Levkoff ( 20 ).

Both models were required to be functioning for at least six months before enrollment. Each site reviewed VA or Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality guidelines for depression care with all providers in each model before the start of the trial. Eight of ten integrated care sites had a psychiatrist or psychologist on site, and all enhanced specialty referral sites had psychiatrists or psychologists available. Conversely, two enhanced specialty referral sites did not have midlevel providers available. The midlevel providers included registered nurses, advanced practice nurses, counselors, and master's-level social workers. However, formal adherence to guidelines was not required. Model fidelity and satisfaction of model criteria were approved by evaluations from the coordinating center before randomization and monitored by a detailed process evaluation, which was complemented by site visits conducted by the coordinating center.

Study outcomes

Primary outcomes were severity of depressive symptoms, as measured by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) ( 23 ), and mental functioning, as measured by the mental component score (MCS) of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36) ( 24 , 25 ), at the three- and six-month follow-ups. Secondary outcomes were remission, the categorical presence or absence of depressive syndromes, as measured by the MINI ( 26 ) at the six-month follow-up, and the presence or absence of a 50 percent decrease in depressive symptoms on the CES-D.

Analyses

Unadjusted comparisons of mean six-month changes in CES-D and MCS scores between treatment groups were made with two-sample t tests. In order to incorporate the additional three-month follow-up data, control for site variation, and adjust for within-person correlation over time, repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with generalized estimating equations was used to simultaneously assess changes in CES-D and MCS scores at three and six months, while allowing for missing data. Logistic regression was used to compare frequencies of a 50 percent improvement on the CES-D scale among participants assigned to integrated care and enhanced specialty referral models; results were adjusted for site. Chi square tests of association were used for unadjusted comparisons of remission categories by treatment group; logistic regression was used to control for site. In regression models, treatment-by-site interactions were examined by using likelihood ratio tests. Because outcomes were qualitatively similar across minor depression, dysthymia, and depression not otherwise specified but were different from major depression, patients were stratified into major depression and other depression categories. Analyses were performed by using the intent-to-treat method. Data were analyzed by using SAS version 8.0 software.

The study was designed to enroll 1,200 patients with depression, so that if 70 percent of the enrollment target was met and an 80 percent follow-up rate was attained, the study would achieve 80 percent power to detect differences in depression outcome scores of 1.7 to 2.4 points or more, using a two-sided test of equality at the .05 level of significance. Recruitment and follow-up requirements were met. Because of this relatively high follow-up rate we performed an available-cases analysis. Strengths and weaknesses of this approach in clinical trials have been addressed in an article by Ware ( 27 ). No interim analyses were planned or performed.

Results

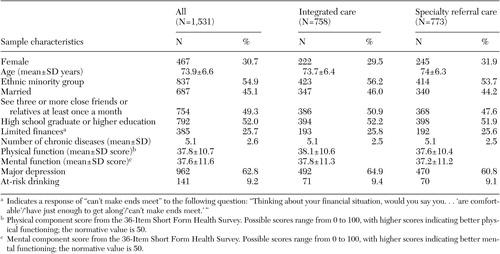

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the 1,531 participants. There were no significant differences between patients in the integrated care and enhanced specialty referral conditions. Mean age was 73.9 years. Almost three-quarters of patients were male (reflecting the significant contribution by the VA sites), 52 percent had a high school education or more, and more than half were from an ethnic minority group (55 percent). Each participant had an average of 5.1 chronic diseases. Most patients had major depression (962 participants, or 63 percent), followed by minor depression (325 participants, or 21 percent), dysthymia (109 participants, or 7 percent), and depression not otherwise specified (135 participants, or 9 percent).

|

Initial analyses assessed whether the service improvements specified in the description of the two models were achieved. Overall, 709 of 999 participants (of all qualifying diagnoses) in the integrated care group (71 percent) attended an appointment with a mental health provider. These percentages actually refer to "all qualifying diagnoses," not just depression, but they do show the different levels of engagement across models. A majority of participants in the integrated care group who attended an appointment were seen in two weeks or less from the time of diagnosis in primary care (506 of 999 participants, or 51 percent). Only 499 of 999 participants in the enhanced specialty referral group (49 percent) ever attended a mental health or substance abuse appointment; only 158 (15 percent) were seen in two weeks or less. These percentages refer to "all qualifying diagnoses," not just depression, but they do show the different levels of engagement across models.

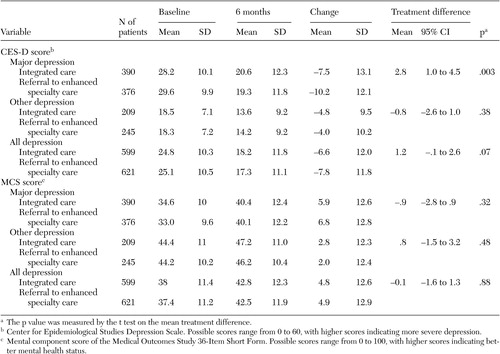

Table 3 shows the mean changes in depression severity from baseline to the six-month follow-up. Overall, depression severity declined in both models as measured by changes in CES-D scores, with a trend toward greater reduction in enhanced specialty referral (7.8 points) compared with integrated care (6.6 points). For major depression, enhanced specialty referral was associated with a significantly greater decline in depression severity compared with integrated care (change in CES-D score for enhanced specialty referral=-10.2±12.1; for integrated care =-7.5±13.1; mean difference in score=2.8, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.0 to 4.5, p=.003). About 75 percent of the decline in CES-D scores occurred in the first three months of the study, but differences didn't become statistically significant until the six-month follow-up point.

|

Mental functioning also improved by 5 points on the MCS over time, but it did not differ between the enhanced specialty referral and integrated care groups ( Table 3 ). Repeated-measures ANOVA models that controlled for site found that the outcome of change in CES-D scores showed significant time effects, with a reduction in depression severity by six months. Although mean reduction in symptoms among patients with major depression was greater during the first three months, there continued to be significant improvement over the entire follow-up period. For other depression, significant improvement was concentrated in the first three months and maintained over the next three months. For the major depression group, there was a significant time-by-treatment interaction demonstrating greater reduction in symptoms over time for enhanced specialty referral.

Secondary analyses seemed to show that the combination of talk therapy plus pharmacotherapy worked better in the enhanced-specialty referral model than in the integrated care model for patients with major depression. The repeated-measures ANOVA model for the outcome of change in CES-D scores also showed that the number of chronic illnesses at baseline was associated with poorer outcome in the subgroup with major depression (p<.001), but age, gender, education, and ethnic group didn't differ in outcomes. The MCS models also show improvement over time for both major and other depression categories, but no differential improvement was found between the enhanced specialty referral and integrated care models. No significant site-by-treatment assignment interactions were found in any of the models. There was no significant difference in remission rates between the integrated care and enhanced specialty referral models.

Discussion

This study compared two systems of interventions designed to improve treatment for depression among older primary care patients. Both the integrated care and enhanced specialty referral models found comparable clinical rates of depression remission and decreases in depression severity over six months for the overall sample. Both the integrated care and enhanced specialty referral models were associated with significant reductions in symptom severity for the aggregate group of patients with major depression, dysthymia, minor depression, or depression not otherwise specified. Compared with integrated care, enhanced specialty referral was associated with a trend toward greater reduction in depression severity. This difference was due to the subgroup with major depression, which showed a statistically significant reduction in depression severity for the enhanced specialty referral model compared with the integrated care model. This finding suggests that there may be an advantage to treatment in specialty provider clinics for more severe forms of depression. In contrast, comparable results occurred for the integrated care and enhanced specialty referral models for dysthymia, minor depression, and depression not otherwise specified.

The PRISM-E study showed that, compared with the integrated care, an enhanced specialty referral model of care resulted in significantly more symptomatic improvement, as measured by change in CES-D scores among the 63 percent of participants with major depression. However, because there was no usual-care arm in the PRISM-E study, it is not possible to ascertain whether either the enhanced specialty referral model or the integrated care model actually resulted in improved outcomes over usual care.

Comparisons with other recent studies are made difficult by clinical and demographic differences that might decrease treatment response in PRISM-E, including a high percentage of male participants (69 percent in PRISM-E, compared with 28 percent in PROSPECT and 35 percent in IMPACT), a greater percentage of persons from ethnic minority groups (55 percent in PRISM-E, compared with 33 percent in PROSPECT and 35 percent in IMPACT), and a higher mean number of medical illnesses (5.1±2.6 in PRISM-E, compared with 3.2±1.7 in IMPACT). It is important to note, however, that secondary analyses in this study showed that only the number of medical illnesses was significantly associated with poorer outcomes among PRISM-E participants.

However, all three studies shared a common type of outcome measure: whether or not patients achieved a 50 percent reduction in a measure of depression symptom severity over six months for IMPACT and PRISM-E and over four months for PROSPECT. Reduction in depression symptom severity was measured by the CES-D for PRISM-E, by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for PROSPECT, and by the Symptom Checklist-90 for IMPACT. Because PRISM-E included participants with major depression, dysthymia, and minor depression, whereas IMPACT enrolled subjects with either major depression or dysthymia and PROSPECT enrolled subjects with either major or minor depression, we were able to compare outcomes by using the appropriate subsets of PRISM-E participants.

IMPACT participants who were treated in the integrated model achieved a 50 percent reduction in severity 49 percent of the time; this reduction was seen 29 percent of the time for comparable patients in PRISM-E. Thirty-one percent of IMPACT participants in the usual-care group experienced a 50 percent improvement, whereas 37 percent of participants assigned to PRISM-E's enhanced specialty referral group improved by 50 percent. Comparison of the relevant subgroups in PROSPECT and PRISM-E shows that 43 percent of participants in integrated care in PROSPECT improved by 50 percent or more, whereas only 31 percent of those in PRISM-E integrated care had that magnitude of improvement. Twenty-nine percent of participants in PROSPECT's usual-care group improved by 50 percent, compared with 34 percent of the participants in PRISM-E's enhanced specialty referral group.

Thus the frequency of improving by 50 percent on a depression symptom severity measure in both PRISM-E systems of treatment was somewhat closer to treatment-as-usual outcomes than to the integrated care outcomes obtained in PROSPECT and IMPACT. Whether this is related to differences in how the models were implemented or in the participant populations is unknown. However, the direction of the significant difference varied across the three studies, as integrated care was more effective than the comparison group (that is, treatment as usual, which might be a form of referral care) in IMPACT and PROSPECT and it was less (or equally as) effective than the comparison group (that is, enhanced specialty referral) in PRISM-E. At minimum, the PRISM-E data show that not all models of integrated care result in better outcomes than all models of specialty referral care.

An earlier report from the PRISM-E study documented that integrated care results in greater access to mental health services (defined as engagement in first visit) ( 21 ). By design, patients in the integrated care group were more likely to be treated by mental health clinicians who were not physicians (426 participants, or 60 percent), whereas patients in the enhanced specialty referral group were more likely to be treated by psychiatrists (299 participants, or 60 percent). However, the differences in treatment intensity were attenuated among those who actually received any mental health services, with patients in the integrated care group having a mean±SE of 4.8±.16 visits and those in the enhanced specialty referral group having a mean±SE 4.2±.22 visits (t=2.31, df=820, p=.02). Other studies have used a four-visit criterion over a six- or 12- month period as a benchmark for minimally adequate care ( 28 ). Perhaps at these minimally adequate, albeit realistic, levels of utilization, the statistical difference in service intensity may not be great enough to drive larger differences in clinical outcomes. This finding also indicates that the enhanced specialty referral model is more effective on a "per visit" basis than the integrated care model. Despite lower participation in care, participants showed greater improvement in the enhanced specialty referral arm.

The PRISM-E study suggests that the type of treatment as well as the treatment arm may influence the outcomes for older patients with major depression. Patients with major depression in the enhanced specialty referral group who were given pharmacological treatment in combination with therapy (as noted on treatment tracking forms) had greater reductions in depressive symptoms than those with no treatment or psychotherapy alone. This finding is consistent with other recent studies demonstrating the benefits of combined therapies ( 29 ). Whether this interaction of treatment type with model was due to the increased use of psychiatrists in the enhanced specialty referral arm is not known. In addition, patient access to these therapies was also influenced by the treatment arm, with patients in the integrated care group more likely to have access to psychotherapy alone (379 participants, or 50 percent, compared with 301 participants, or 39 percent) and patients in the enhanced specialty referral group more likely to receive pharmacological treatment alone (116 participants, or 15 percent, compared with 45 participants, or 6 percent) or evaluation alone (108 participants, or 14 percent, compared with 38 participants, or 5 percent). Approximately similar numbers in both groups received combination therapy (that is psychotherapy and pharmacology; 288 participants, or 38 percent, in the integrated care group compared with 247 participants, or 32 percent, in the enhanced specialty referral group). The PRISM-E results indicate that there are still opportunities for improvement by increasing the application of the most efficacious therapies.

The PRISM-E study suggests that the type of treatment as well as the treatment arm may influence the outcomes for older patients with a large number of comorbid medical conditions. Our ability to assess and retain such an ethnically and clinically diverse cohort underscores the importance of systematic and culturally competent screening ( 30 ). The depression study group included major depression, minor depression, dysthymia, and depression not otherwise specified, allowing for comprehensive comparison of treatment outcomes across the depression spectrum. Most important, the study used a relatively realistic implementation strategy. To be eligible for inclusion as a study site, clinics had to demonstrate that they met very specific criteria for both the integrated and enhanced-referral models of care, but clinicians were able to follow their own practice style. Thus clinician behaviors and patient problems were closer to the typical clinical situation than in studies focused on a single, pure diagnostic group with highly structured treatment protocols. It is important to note that the cost of mental health and substance abuse treatment per patient per year did not differ significantly across models ( 28 ). Further analyses on cost of care will be presented in subsequent papers.

There are several important caveats to the interpretation of the study findings. First, we tested the comparative efficacy of two system-level models for organizing depression treatment among older primary care patients. Thus our study design did not include a usual-care group, so we are not able to make the comparison between treated and control groups. Second, our findings may not be directly generalizable to other settings, given the large number of male veterans in the study sample. Third, a significant difference in the degree of improvement of depressive symptoms was demonstrated between participants with major depression assigned to the enhanced specialty referral model and those assigned to the integrated care model. However, the clinical importance is open to some question, given the lack of a difference in the remission rate after six months. Fourth, findings such as the interaction of treatment type and model type based on the secondary analysis strategy employing repeated-measures ANOVA modeling are inherently weakened by selection biases affecting the analyzed subgroups. Finally, we must note that the study was randomized but not blinded, which could have led to biased assessment by research personnel who performed the follow-up evaluations. We know of no reason to believe that the participants would have a reason to be biased in favor of one model over the other.

Conclusions

The results of this study provide a unique perspective on the complex question of how to best organize and deliver mental health services to older adults who predominantly seek and receive psychiatric treatment in primary care settings. For older primary care patients with less severe forms of depression, PRISM-E data suggest that integrated care may be effective. It offers elderly patients with less severe depression the access and convenience of "one-stop shopping" and comparable clinical outcomes. At the same time, enhanced specialty referral (which must be clearly differentiated from the usual level of referral care available in most clinics in the United States) was associated with slightly better symptomatic outcomes (but not better remission rates or functional outcomes) for patients with major depression, perhaps because of the greater access to specialized psychiatric and medication management services. However, the patients with major depression in the integrated care model also improved over time, and this type of care may be an option for some patients, particularly those for whom stigma may be a major barrier to care. These findings lend empirical support to the recent recommendations of the Older Adults Subcommittee of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health ( 11 ) for greater access to providers with expertise in geriatric psychiatry, greater consumer choice and access to services, and greater coordination of mental health services with primary health care.

Acknowledgments

The federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and its three centers, the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS), the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, and the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, funded and participated in this initiative, with CMHS serving as the lead. The Department of Veterans Affairs, the Health Resources Services Administration, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services provided additional support and collaboration. This article was written solely from the perspective of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the federal agencies.

1. Barkin RL, Schwer WA, Barkin SJ: Recognition and management of depression in primary care: a focus on the elderly: a pharmacotherapeutic overview of the selection process among the traditional and new antidepressants. American Journal of Therapeutics 7:205-226, 2000Google Scholar

2. Lyness JK, King DA, Cox C, et al: The importance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients: prevalence and associated functional disability. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47:647-652, 1999Google Scholar

3. Alexopoulos GS, Vrontou C, Kakuma T, et al: Disability in geriatric depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:877-885, 1996Google Scholar

4. Callahan CM, Hui SL, Nienaber NA, et al: Longitudinal study of depression and health services use among elderly primary care patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 42:833-838, 1994Google Scholar

5. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED: Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biological Psychiatry 52:193-204, 2002Google Scholar

6. Luber MP, Meyers BS, Williams-Russo PG, et al: Depression and service utilization in elderly primary care patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 9:169-176, 2001Google Scholar

7. Klap R, Tschantz K, Unützer J: Caring for mental disorders in the United States: a focus on older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 11:517-524, 2003Google Scholar

8. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

9. Kaplan MS, Adamek ME, Calderon A: Managing depressed and suicidal geriatric patients: differences among primary care physicians. Gerontologist 39:41-425, 1999Google Scholar

10. Bartels SJ, Horn S, Sharkey P, et al: Treatment of depression in older primary care patients in health maintenance organizations. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 27:215-231, 1997Google Scholar

11. Bartels SJ: Improving the United States' system of care for older adults with mental illness: findings and recommendations for the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 11:486-497, 2003Google Scholar

12. Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, et al: Changing physician performance: a systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA 274:700-705, 1995Google Scholar

13. Coyne JC, Thompson R, Palmer SC, et al: Should we screen for depression? Caveats and potential pitfalls. Journal of the American Association for Applied and Preventive Psychology 9:101-121, 2000Google Scholar

14. Grimshaw JM, Russell IT: Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet 342:1317-1322, 1993Google Scholar

15. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026-1031, 1995Google Scholar

16. Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:924-932, 1996Google Scholar

17. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:1109-1115, 1999Google Scholar

18. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al: Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:2836-2845, 2002Google Scholar

19. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF III, et al: Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:1081-1091, 2004Google Scholar

20. Levkoff SE, Chen H, Coakley E, et al: Design and sample characteristics of the PRISM-E multisite randomized trial to improve behavioral health care for the elderly. Journal of Health and Aging 16:3-27, 2004Google Scholar

21. Bartels SJ, Coakley E, Zubritsky C, et al: Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement in integrated and enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1455-1462, 2004Google Scholar

22. Goldberg DP: The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. Oxford England, Oxford University Press, 1972Google Scholar

23. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385-401, 1977Google Scholar

24. Ware JE Jr, Snow KK, Kosinski M, et al: SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, Mass, New England Medical Center, Health Institute, 1997Google Scholar

25. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30:473-481, 1992Google Scholar

26. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD 10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 20):22-33 quiz 34-57, 1998Google Scholar

27. Ware JH: Interpreting incomplete data in studies of diet and weight loss. New England Journal of Medicine 348:2136-2137, 2003Google Scholar

28. Domino M, Maxwell J, Cheal K, et al: The influence of integration on the expenditures and costs of mental health and substance use care: results from the PRISM-E Study. Presented at National Institute of Mental Health Conference on Mental Health Services Research, Bethesda, Md, Jul 18-19, 2005Google Scholar

29. Arean PA, Cook BL: Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late life depression. Biological Psychiatry 52:293-303, 2002Google Scholar

30. Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al: Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research 38:613-629, 2003Google Scholar