Managing Medicaid Behavioral Health Care: Findings of a National Survey in the Year 2000

According to the most recent estimates for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. spending on mental health care in 2001 was $85.4 billion ( 1 ). Medicaid represents an estimated 44 percent of all public mental health expenditures ($53.6 billion) and is the largest federal grant-in-aid program for states ( 1 ). As the single largest source of funding for mental health services in the United States, Medicaid has been influential in shaping today's public mental health and substance abuse systems of care.

Originally authorized in 1965, Medicaid is a joint program of the federal and state governments and is characterized by joint federal-state financing, state administration of the program under federal standards, and eligibility that is tied to the receipt of cash welfare or disability benefits ( 2 ). Federal matching payments are determined by a formula based on state per-capita income, with the federal share ranging from a low of 50 percent to a high of 80 percent of expenditures ( 3 ).

To receive federal matching payments, states must offer a standard package of Medicaid benefits that includes physician and hospital services; laboratory and X-ray services; nursing home and home health services for adults; family planning and prenatal care; and early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment for children. States may also cover a range of optional services, including treatment for mental and substance use disorders ( 4 ).

Traditionally, Medicaid services were provided under fee-for-service arrangements. However, fiscal pressures became the impetus for states to design new financing and delivery arrangements to decrease the pressure on Medicaid resources while continuing to expand access to care for the poor and uninsured. In the early 1980s, the federal government gave permission, under a series of waivers of Social Security Act requirements, for states to experiment with mandatory enrollment in managed care programs. Later, under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, most states were allowed to mandate enrollment for certain beneficiaries without a waiver. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, between 1991 and 2000, the number of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in managed care increased from 2.7 to 18.8 million, and as of June 2000, 43 states had more than 25 percent of their Medicaid population enrolled in managed care ( 5 ).

Historically, states have varied in their use of types of managed care arrangements. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) describes managed care arrangements as managed care organizations, prepaid health plans, and primary care case management programs. Managed care organizations are health maintenance organizations (HMOs) that provide a comprehensive health benefits package, including both health and behavioral health services, and are financed under a capitation arrangement. The HMO is provided a set amount of financing regardless of actual utilization. Prepaid health plans—such as specialty mental health carve-outs—are also funded through capitation contracts but provide something less than comprehensive health benefits. States have also used managed fee-for-service arrangements, such as primary care case management programs in which physicians are paid for primary care and are also paid a monthly fee to provide gate keeping to specialty care for their enrolled patients.

At the time of this study (the year 2000), little detailed information on managed behavioral health care was available from CMS. The publicly available CMS database flagged which prepaid health plans were mental health carve-outs but did not provide information on the mental health benefits provided by managed care organizations, such as HMOs, or primary care case management programs. This study was designed to address that important gap.

When we began our survey, contemporaneous efforts were under way to provide information on the extent and characteristics of Medicaid managed care programs. Four of those initiatives informed our study. First, SAMHSA provided an annual profile on public-sector managed behavioral health care that was based on data collected annually with a standard form developed by the Lewin Group ( 6 ). The SAMHSA report differs from our study in that it includes non-Medicaid managed care programs and provides enrollment and expenditure data at the program level.

SAMHSA also funded the Healthcare Reform Tracking Project ( 7 ). The tracking project provided an annual update based on a survey and also attempted to analyze the impact of managed care reforms on children and adolescents with serious behavioral health problems. Like the Lewin survey, this survey of children's mental health directors focused on public-sector initiatives (both Medicaid and non-Medicaid), included both mental health and substance abuse treatment, and did not rely solely on Medicaid authority respondents. The investigators also posed a series of closed-ended questions to gather subjective opinions on adequacy, capacity, and coordination of care.

The other two initiatives that deserve mention were not tracking studies but were attempts to characterize the important issues in the development of Medicaid managed care programs in the states. Both the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law and the Center for Health Policy Research at George Washington University developed written technical assistance documents in the mid-to-late 1990s that outlined key factors in the implementation of Medicaid managed care ( 8 , 9 ). Investigators at George Washington University based their report on a nationwide study of Medicaid managed care contracts. Unfortunately, this study was limited to 54 contracts nationally, only 12 of which were behavioral health contracts ( 9 ). However, by identifying some of the key factors, these reports influenced the domains that would be covered in future survey work.

Unfortunately, none of these studies were published in peer-reviewed literature. Although they were useful in setting a context, we found them lacking for our purposes—in content (specific data elements included), comprehensiveness (some had information from only selected states, none had every managed care plan in the United States), and reliability (verifying the accuracy of Medicaid program information when surveying non-Medicaid agency respondents). Our study was designed to avoid some of the limitations of the prior studies and to address a gap in the literature.

Methods

The study described in this article was part of a larger research effort, Healthcare for Communities, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ( 10 ). Healthcare for Communities is a national study designed to understand access, costs, and quality of care for people with behavioral health problems treated in the public and private sectors. The research questions that guided the study included the following: To what extent were states using managed care arrangements to manage behavioral health benefits in the year 2000? What was included in the behavioral health benefit packages under managed care? Which enrollees were typically covered? Were comprehensive health plans or specialty prepaid health plans (carve-outs) managing benefits? Were more states using for-profit or nonprofit vendors, and were these vendors at risk? Was there any relationship between benefit coverage, type of program, and reimbursement arrangement?

An initial set of survey questions was developed on the basis of prior case study work that documented the characteristics of Medicaid managed care arrangements ( 11 ). We were especially concerned about the potentially negative relationship between respondent burden and response rate, and therefore we designed the survey to collect only a minimum data set to be merged with existing data from CMS.

Some states had more than one managed care program operating under either federal waivers or state amendments to the Medicaid plan. To minimize respondent burden, individual plans were sorted into the waiver programs on the basis of key characteristics reported in the CMS Enrollment Report 2000 ( 12 ). These characteristics included type of waiver, Section 1115 or 1915(b) of the Social Security Act; managed care arrangement, meaning managed care organization, prepaid health plan, or primary care case management; and type of financing, such as full capitation, partial capitation, or fee for service. Respondents verified the sorting of individual health plans into waiver programs and then reported, by waiver program, on a limited number of other characteristics, such as enrollee type, mental health benefits, substance abuse benefits, and risk sharing. Individual surveys were customized for each state Medicaid agency.

A cover letter, consent form, and survey were mailed to the 51 state Medicaid administrators in March 2000. The materials asked respondents to report on their Medicaid waiver programs for fiscal year 2000. Follow-up continued until a 100 percent response rate was achieved, which extended the field period into early 2002. All survey data were entered, cleaned, and merged with data elements from the CMS enrollment report, which were verified by survey respondents. Medicaid managed care plans providing transportation only, and no health-related services, were excluded from the survey and the analysis.

Whenever possible, analyses were conducted at the state, waiver program, and plan level. Many states had more than one waiver program as well as voluntary enrollment programs. A state was included in a count for the state analyses if the respondent indicated that the particular answer applied to any of their waiver programs. There were also two questions in the survey for which Medicaid agency respondents were asked to "check all that apply" for a particular waiver program so that not all data elements were available at the plan level. In those instances, we report findings at the waiver program level.

Results

Use of managed care arrangements

Thirty-one states (61 percent) reported that they used managed care programs to manage both mental health and substance abuse benefits for at least some of their beneficiaries in fiscal year 2000. An additional five states used managed care arrangements to manage mental health benefits only. Only two states reported having no Medicaid managed care programs at all, and an additional 13 states had managed care programs but did not manage mental health or substance abuse benefits.

Behavioral health benefit packages

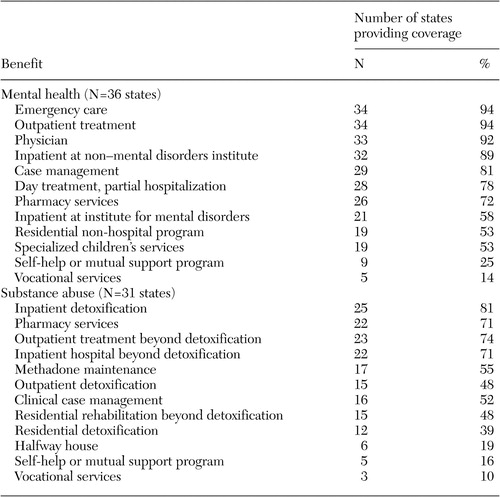

First, for state-level analysis of mental health benefits, Table 1 shows that most states provided an array of emergency, inpatient, and outpatient services for at least some of their Medicaid beneficiaries. States were included in this count if the respondent indicated the management of either mental health or both mental health and substance abuse benefits for any of the state's waiver programs. This result is not surprising given that inpatient and physician services are federally mandated Medicaid services and are therefore likely to be included in the benefit design for waiver programs. It is noteworthy, however, that most states were also providing optional services under managed care programs. For example, most of the Medicaid agencies reported the inclusion of case management as a covered service, and over three-quarters also reported coverage of day treatment or partial hospitalization. Most states also covered psychotropic medications. Surprisingly, a small number of states reported that even self-help or mutual support groups and specialized vocational services were part of the behavioral health benefit package for at least some of their waiver programs. Although neither of these services would have met the traditional definition of medical services, they are often advocated as important psychosocial adjuncts to treatment for people with serious mental illnesses.

|

Of the 31 states providing substance abuse benefits under Medicaid managed care arrangements, the majority provided inpatient detoxification, inpatient treatment, pharmacy services, and outpatient treatment for at least some of their beneficiaries. Again, the coverage of inpatient care is among the federally mandated Medicaid benefits. However, we found it interesting that states reported covering a wide array of other substance abuse benefits, including pharmacy benefits for substance use disorders, outpatient treatment, and methadone maintenance. Residential rehabilitation for substance use disorders was covered for at least some beneficiaries in almost half of the states reporting coverage of substance abuse treatment. These findings seem to belie the conventional wisdom that coverage of substance use disorders is generally poor under Medicaid and might be especially poor with the delegation of management to private health plans under managed care programs.

Covered enrollees

Not surprisingly, all state Medicaid agencies using managed care arrangements reported that these waiver programs covered beneficiaries of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. Most states also reported coverage of populations receiving Supplemental Security Income (27 states), pregnant women (23 states), and children enrolled in State Children's Health Insurance Programs (26 states). Although eligibility status is not a perfect proxy for mental disability status, the broader inclusion of Supplemental Security Income recipients means that more people with serious mental illnesses were in the managed care population in 2000.

Comprehensive health plans and carve-outs

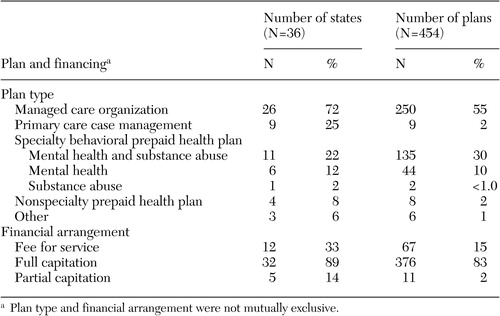

States used several types of managed care arrangements. Table 2 presents data on type of state financial arrangement and type of individual health plans offered among states. At the state level, most states that were using managed care arrangements reported using managed care organization arrangements. One-quarter of the states reported using primary care case management arrangements, which are fee-for-service programs that employ primary care provider gatekeepers to manage access to specialty care. More than one-third of the states reported the use of specialty carve-out arrangements (prepaid health plans) either to manage both mental health and substance abuse or just mental health services.

|

When these data were analyzed on a plan level, however, the relative prominence of different types of arrangements began to emerge. Primary care case management programs represented only a small fraction of health plans. By contrast, managed care organization arrangements accounted for most of the health plans. The behavioral health carve-out plans accounted for 40 percent of plans nationwide.

Vendors and risk

States also reported on their use of vendors across their waiver programs. Two-thirds of the states reported using for-profit vendors to manage behavioral health benefits. Half of the states also reported using nonprofit vendors, and 41 percent of the states reported using governmental or quasi-governmental vendors, such as county government or county-level mental health boards, to manage behavioral health benefits for at least some of their beneficiaries.

The CMS Enrollment Report 2000 also provided information on the financial arrangements of all of the Medicaid managed care plans (see Table 2 ). To supplement these data, we collected information on the risk arrangements between the states and their vendors. One-third of the states reported using fee-for-service arrangements to reimburse health plans (no risk). However, capitation contracts predominated, with the vast majority of state Medicaid agencies reporting that they used full capitation contracts with vendors. At the individual health plan level, state Medicaid agencies reported that almost 83 percent of their vendors had full capitation contracts, with only relatively few vendors paid on a fee-for-service basis.

Because capitation contracts typically put the vendor at full risk of cost overruns and adequate risk-adjustment schemes continue to be elusive, some states have moved to create contract mechanisms—such as risk corridors—that allow the state to share some of the risk with vendors. This development arose in recognition that even a relatively small number of unpredictably expensive enrollees could undermine the financial position of a small health plan. A quarter of the state Medicaid agencies reported that some of their managed care vendors assumed all of the risk, although as a matter of federal law it is not clear that a state can ever fully shift its risk to a private entity regardless of how the contract is worded. Twelve states explicitly shared risk with their vendors through such mechanisms as risk corridors and stop-loss arrangements.

Relationships among variables

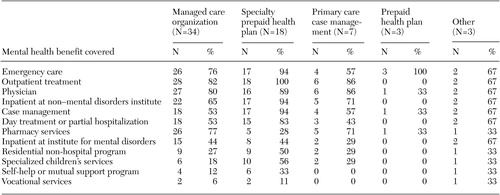

As reported in Table 3 , state waiver programs that used specialty carveout plans—the prepaid health plans—tended to be more comprehensive in terms of the types of mental health services covered than the waiver programs using either managed care organizations or primary care case management arrangements. For example, almost all such programs included case management in the benefit design, compared with only half of managed care organization and primary care case management programs. By contrast, waiver programs that used specialty carve-out vendors generally did not manage pharmacy benefits, whereas three-quarters of waiver programs with managed care organizations managed the pharmacy benefit for psychotropic medications. Waiver programs with specialty carve-outs were also much more likely to include residential services, specialty children's services, vocational services, and self-help or mutual support programs, perhaps because specialty carve-out organizations have expertise in developing provider networks—including traditional safety net providers—that can offer these kinds of specialty programs. There were only small differences in the pattern of covered mental health benefits between programs that used full capitation financing and waiver programs that provided reimbursement under fee-for-service arrangements (not shown).

|

Discussion

As mentioned earlier, the strength of this study is its completeness. We achieved a 100 percent response rate and were able to include every existing Medicaid managed care plan in the United States in our analysis. However, in order to achieve that response rate, the number of data elements collected was very limited. In addition, because our respondents were state Medicaid agency administrators and we were merging our survey items with CMS data elements, we had to use CMS terminology to define type of managed care arrangement and type of financing arrangement and to specify services. These decisions were clearly trade-offs that limited the usefulness of the data. In addition, the field period had to be elongated to achieve a 100 percent response rate, which means that our findings are a point-in-time snapshot rather than a current picture of managed care. Because data collection extended into 2002, recall may also have been a problem for the respondents in the 15 states that did not provide complete data within the initial field period. Finally, the information on benefits is for Medicaid managed care only. Medicaid services provided under traditional fee-for-service arrangements, as well as non-Medicaid services, may be available to Medicaid beneficiaries.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this cross-sectional survey of state Medicaid agencies provides a national overview of managed behavioral health care in the Medicaid program in the year 2000. Most states were using managed care, with most contracting for the broad range of their Medicaid beneficiaries, including people with serious mental illness. The array of mental health and substance abuse services included in the benefit design varied across states, but, especially on the substance abuse side, benefit design was more comprehensive on the outpatient side than conventional wisdom might have suggested. However, although our study can document the nominal benefits that were available in the year 2000, it cannot address the extent to which access to care may be constrained by utilization management or low reimbursement rates offered to specialty providers.

The kinds of managed care arrangements used by states varied considerably, but clearly a large number of public-sector patients were being served in HMO-type arrangements that may not have had specialty expertise in the management of behavioral health care. We were not able to collect information on the extent to which managed care organizations were carving out their behavioral health benefits and whether they might be putting their own vendors at risk. On the other hand, a surprisingly high number of states reported managing care with governmental or quasi-governmental entities as vendors, perhaps suggesting that state policy makers saw an important role for public-sector entities in the delivery of care to vulnerable populations.

Beyond noting that there were differences across the states, what might these differences predict in terms of impact on access, quality, cost, and outcomes? And what are the implications for national and state Medicaid policy? For example, the fact that large numbers of vulnerable individuals are receiving their behavioral health services through capitated, at-risk plans could pose a problem for people with serious mental illnesses if health plans respond to capitation incentives by denying access or needed treatment. Studies published since our survey in 2000 do not suggest that the use of managed care within Medicaid has decreased access to ambulatory care or the quality of that care compared with fee-for-service arrangements ( 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ), but there may be risk-related differences between carve-outs and integrated arrangements in access to specific services ( 18 ).

It is arguable that the needs of people with serious mental illness might be better served by specialty carve-out plans given that our survey suggests that those plans tend to have a more comprehensive package of specialty ambulatory services. On the other hand, it could be argued that selective enrollment of people with serious mental illness into carve-out plans could endanger the financial stability of those plans if states do not provide risk adjustment on the basis of disability status (which most do not). In addition, Medicaid beneficiaries in carve-out plans may be disadvantaged by the lack of integration between their health and behavioral health care (assuming, again, that managed care organizations are actually providing integrated care and not carving out). Cross-sectional surveys can raise these questions but cannot adequately address them. For example, other investigators have raised questions about the extent to which Medicaid agencies have prepared themselves to become value-based purchasers, such as whether they are requiring that health plans report on quality indicators and including performance penalties in their contracts with health plans ( 19 ). Others have examined the profit status of health plans to discover whether organizational characteristics are related to service use and quality ( 20 ).

One pressing policy question is whether public-sector mental health authorities have sufficient influence on the development of Medicaid policy ( 21 ). Because Medicaid agencies lie outside of the mental health and substance abuse arena, if state authorities are to have an influence on the delivery of behavioral health benefits within Medicaid, they must aggressively seek opportunities to influence the development of policy at all levels of government, both federal and state. New Balanced Budget Act requirements (for "actuarial soundness") may mean that the flexibility of managed care will be substantially reduced and will undoubtedly have an effect on state policy making. In addition, a few states (such as Tennessee) have had such long-standing problems with their Medicaid managed care systems that policy makers are seriously contemplating a return to fee-for-service systems. The potential impact of such radical changes on the public mental health sector is unknown.

Conclusions

President Bush's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health argued for seamless systems of care at the local level, regardless of source of financing ( 22 ). In far too few states, the Medicaid and public-sector systems are managed as one. In other states, these systems continue to operate in parallel. Whichever arrangements states choose—and whether or not they put managed care plans at risk—the commission argued forcefully that the agenda of policy makers, providers, and consumers in the second half of the decade should be focused on increasing the delivery of evidence-based practices and thereby the quality of care and responsiveness to consumers. Although these issues are high on the agenda of mental health advocates, it remains to be seen whether these issues can compete with the need to reduce Medicaid budgets at the federal and state levels.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the contribution of Jennifer Magnabosco in assisting with data collection, data management, and analysis.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: National Expenditures for Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse Treatment 1991-2001. DHHS pub SMA 05-3999, 2005. Available at www.samhsa.gov/spendingestimates/toc.aspxGoogle Scholar

2. Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC, Physician Payment Review Commission, 1997Google Scholar

3. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured: Medicaid Facts. Washington, DC, Kaiser Family Foundation, June 1998Google Scholar

4. Iglehart JK: The American health care system. New England Journal of Medicine 328:896-900, 1993Google Scholar

5. Kaiser Family Foundation: The Medicaid Resource Book, July 2002. Available at www.kff.org/medicaid/2236-index.cfmGoogle Scholar

6. Lewin Group: SAMHSA Tracking System: 2000, State Profile on Public Sector Managed Behavioral Health Care. Falls Church, Va, Lewin Group, Feb 9, 2001Google Scholar

7. Stroul BA, Pires SA, Armstrong MI: Health Care Reform Tracking Project: Tracking State Managed Care Systems as They Affect Children and Adolescents With Behavioral Health Disorders and Their Families—2000 State Survey. Tampa, Fla, University of South Florida, 2000Google Scholar

8. Managing Managed Care for Publicly Financed Mental Health Services. Washington, DC, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, Nov 1995Google Scholar

9. Rosenbaum S, Silver K, Wehr, E: An Evaluation of Contracts Between State Medicaid Agencies and Managed Care Organizations for the Prevention and Treatment of Mental Illness and Substance Abuse Disorders. SAMHSA Managed Care Technical Assistance Series, vol 2. Washington, DC, George Washington University, Center for Health Policy Research, Aug 1997Google Scholar

10. Sturm R, Gresenz C, Sherbourne C, et al: The design of Healthcare for Communities: a study of health care delivery for alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health conditions. Inquiry 36:221-233, 1999Google Scholar

11. Ridgely MS, Giard J, Shern D, et al: Managed behavioral health care: an instrument to characterize critical elements of public sector programs. Health Services Research 37:1105-1123, 2002Google Scholar

12. CMS Enrollment Report. Baltimore, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2000Google Scholar

13. Cook JA, Heflinger CA, Hoven CW, et al: A multi-site study of Medicaid funded managed care versus fee-for-service plans' effects on mental health service utilization of children with severe emotional disturbance. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 31:384-402, 2004Google Scholar

14. Bigelow DA, McFarland BH, McCamant, LE et al: Effect of managed care on access to mental health services among Medicaid enrollees receiving substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services 55:775-779, 2004Google Scholar

15. Rothbard AB, Kuno E, Hadley TR, et al: Psychiatric service utilization and cost for persona with schizophrenia in a Medicaid managed care program. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 31:1-12, 2004Google Scholar

16. Bouchery E, Harwood H: The Nebraska Medicaid managed behavioral health care initiative: impacts on utilization, expenditures and quality of care for mental health. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:93-108, 2003Google Scholar

17. Ettner SL, Denmead G, Dilonardo J, et al: The impact of managed care on the substance abuse treatment patterns and outcomes of Medicaid beneficiaries: Maryland's HealthChoice program. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:41-62, 2003Google Scholar

18. Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AF: The effect of managed behavioral health carve out on quality of care for Medicaid patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:442-448, 2004Google Scholar

19. Landon BE, Schneider EC, Tobias C, et al: The evolution of quality management in Medicaid managed care. Health Affairs 23(4):245-254, 2004Google Scholar

20. Landon BE, Epstein AM: For-profit and not-for-profit health plans participating in Medicaid. Health Affairs 20(3):162-171, 2001Google Scholar

21. Frank RG, Goldman HH, Hogan M: Medicaid and mental health: be careful what you ask for. Health Affairs 22(1):101-113, 2003Google Scholar

22. President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, Subcommittee on Medicaid: Policy Options, Jan 31, 2003. Available at http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov/subcommittee/medicaid013103.doc. Accessed Feb 5, 2003Google Scholar