Racial Differences in Stigmatizing Attitudes Toward People With Mental Illness

The Surgeon General's ( 1 ) report on mental illness highlighted stigma as a major impediment to utilizing and receiving adequate mental health services, especially among racial and ethnic minority groups. Recent research supports the Surgeon General's views ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). For example, Sirey and colleagues ( 8 , 9 ) found that lower perceived stigma was associated with greater medication adherence among adult patients with major depressive disorder and that heightened stigma predicted treatment discontinuation. Researchers have hypothesized that stigmatizing attitudes may deter individuals from seeking care because, as Corrigan ( 10 ) concluded, "social-cognitive processes motivate people to avoid the label of mental illness that results when people are associated with mental health care." Researchers also hypothesize that members of racial minority groups may be more reluctant to seek needed services because they hold even stronger negative attitudes than Caucasians.

Racial and ethnic differences in stigmatizing attitudes have received remarkably little empirical attention. Some studies have found that African Americans and persons from other ethnic minority groups hold more negative attitudes than Caucasians do ( 11 , 12 ); however, the generalizability of these studies is limited by nonrepresentative samples. One recent qualitative study that used focus groups found that African Americans held stigmatizing attitudes about people with mental illness and that these attitudes negatively influenced attitudes toward seeking treatment for mental illness ( 13 ). According to the authors, "the only debate among participants was whether African Americans stigmatized mental illness more than other groups." We addressed this question in our study by using a Caucasian comparison group, and we used a nationally representative sample to improve on the lack of generalizability of previous studies.

One of the key components of stigmatizing responses to persons with mental illness involves perceptions of dangerousness ( 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ). Whaley ( 18 ) conducted the only nationally representative study that we know of that examined racial and ethnic differences in perceptions of dangerousness. He found that Asian-Pacific Islander, African-American, and Hispanic respondents perceived individuals with mental illness as more dangerous than did Caucasian respondents. He also found that African Americans associated mental illness with a heightened risk of violence, regardless of their level of contact with persons who had mental illness.

This study had two purposes. First, we examined whether Whaley's ( 18 ) important findings among African Americans of heightened perceived danger of persons with mental illness could be replicated with a different method—one that used vignette descriptions of people with specific mental illnesses rather than survey items about people with mental illness in general. Second, we broadened our focus and extended the literature by examining not only perceptions of danger but related attitudes that may also be important in shaping public responses to people with mental illness. We might expect that if African Americans tend to view people with mental illness as more prone to violence than Caucasians do, then African Americans might also assign more blame and responsibility for any violent acts perpetrated by people with mental illness, thereby increasing rejecting attitudes and punishing behaviors ( 10 ). We therefore asked whether heightened perceived dangerousness among African Americans translates into a heightened tendency to blame and endorse punishment of people with mental illness if they are violent.

Methods

Sample

Data for our analyses were obtained from a study designed to examine whether and to what extent information gleaned from the Human Genome Project might affect the stigma of mental illness. The target population comprised persons aged 18 and older living in the continental United States in households with telephones. The sampling frame was derived from a list-assisted, random-digit-dialed telephone frame. Telephone interviews were conducted with a multiethnic sample of 1,241 adults between June 2002 and March 2003. The response rate was 62 percent. All results were weighted to take into account poststratification adjustment to national counts by race and ethnicity and different probabilities of selection associated with the sampling plan. Survey commands in the STATA software program for complex survey designs were used to estimate standard errors and conduct statistical tests. Institutional review board approval was obtained for the study.

We focused our analyses on the 118 African American and 913 Caucasian survey respondents. To evaluate sample selection bias, we compared the sample by race with 2000 census data for gender, educational attainment, household income, and age. Correspondence of our sample with the census was quite close for both African Americans and Caucasians with respect to age and income (details are available on request from DMA). Our sample overrepresented women in both groups (64 percent of the African-American analysis sample compared with 53 percent of the census; 65 percent of the Caucasian analysis sample compared with 51 percent of the census) and also included more highly educated African Americans (33 percent of the analysis sample aged 25 years and older were college graduates compared with 20 percent of the black census population). As a check for sample selection bias, we examined whether the effects of race on the dependent variables of interest (reported below) varied significantly by gender, level of educational attainment, or age and found that they did not (results available on request).

The African American and Caucasian subsamples were similar in terms of gender proportion and educational attainment. African Americans were significantly younger and reported lower incomes than Caucasians (F=22.15, df=1, 669, p<.001, and F=8.17, df=1, 669, p<.01, respectively). These demographic variables were controlled for in the multivariate analyses.

Vignettes

Respondents were randomly assigned to hear one vignette describing a hypothetical person with major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, or one of a number of physical illnesses. After the vignettes, respondents were queried about their attitudes, opinions, and beliefs about the described person. Because we wanted to know about the stigma associated with mental illnesses, we focused our analyses on the 81 African-American and 590 Caucasian respondents who were randomly assigned to hear either a major depressive disorder or schizophrenia vignette. In the vignette descriptions, the vignette subject's gender, socioeconomic status (three levels), and cause of the illness (strongly genetic, partly genetic, or not genetic) were randomly varied. Also, the vignette subject's race and ethnicity were matched to those of the respondent. Below is one version of the vignette; bracketed text indicates characteristics that are varied.

"Imagine a person named John. He is a single, 25-year-old [white man. Since graduating from high school, John has been steadily employed and makes a decent living]. Usually, John gets along well with his family and coworkers. He enjoys reading and going out with friends. About a year ago, [John started thinking that people around him were spying on him and trying to hurt him. He became convinced that people could hear what he was thinking. He also heard voices when no one else was around. Sometimes he even thought people on TV were sending messages especially to him. After living this way for about six months, John was admitted to a psychiatric hospital and was told that he had an illness called "schizophrenia." He was treated in the hospital for two weeks and was then released.] He has been out of the hospital for six months now and is doing OK. Now, let me tell you something about what caused John's problem. When he was in the hospital, an expert in genetics said that John's problem was [due to genetic factors. In other words, his problem had a very strong genetic or hereditary component.]"

Measures

Dependent variables. Three single-item measures were used as dependent variables. The first, violence, was measured with the following item: "In your opinion, how likely is it that John would do something violent toward other people? Possible responses were "very likely," "somewhat likely," "not very likely," and "not likely at all." The second, blame, was measured with "If John did something violent as a result of the problems I described, do you think it would …" "definitely be his fault," "probably be his fault," "probably not be his fault," "definitely not be his fault." The third, punishment, was measured with "If John did something violent because of his problem, he should be dealt with by the police and courts just like any other person would be." Possible responses were "strongly agree," "somewhat agree," "somewhat disagree," and "strongly disagree."

Independent variable. Race was measured by the self-identification of the respondent as "black or African American," scored 1, or "white," scored 0. Other racial and ethnic groups were not included in the analyses.

Covariates. We controlled for sociodemographic variables that were potential correlates of race and could account for racial differences in attitudes toward people with mental illnesses. These were assessed before the vignette was presented. Demographic variables included age, in years; education (less than high school, 1; high school or technical school, 2; some college, 3; and college graduate or higher education, 4); household income (less than $20,000, 1; $20,000 to $40,000, 2; $40,000 to 60,000, 3; $60,000 to $80,000, 4; and $80,000 or more, 5); political conservatism (very liberal, 1; somewhat liberal, 2; moderate, 3; somewhat conservative, 4; and very conservative, 5); and dummy variables for religion with Protestant as the reference category (choices were Catholic, other religion, and no or unknown religion).

Analysis

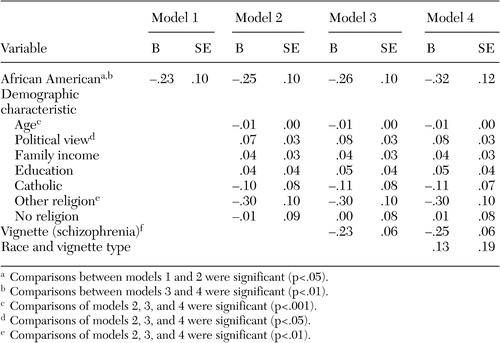

We conducted four multiple regressions for each of the three dependent variables to examine differences between African Americans and Caucasians in perceived dangerousness, blame, and punishment. The same predictors were used for each dependent variable. In the first model, race alone was entered. The second model added age, income, education, political view, and religion. The third model added a variable indicating whether the respondent was randomly assigned a vignette describing schizophrenia or major depressive disorder. To determine whether the effect of race was different for people assigned the schizophrenia as opposed to the major depression vignette, the fourth model added an interaction term for race and disorder type. Regression coefficients and standard errors are presented in Tables 1 through 3 . Missing values for predictor variables were replaced by using conditional mean imputation ( 19 ).

|

a The N differed slightly for each dependent variable because of missing data for some respondents.

|

Results

Perceptions of dangerousness

The first model ( Table 1 ) showed that African Americans were more likely than Caucasians to perceive that individuals with mental illness—schizophrenia and major depression in this study—were dangerous (B=.22, t=2.14, df=629, p<.05). The second model showed that the effect of race remained significant even with sociodemographic controls (B=.25, t=2.26, df=621, p<.05) and that none of these controls were significantly associated with perceived dangerousness. The third model indicated that respondents believed that the person described in the schizophrenia vignette was more likely to do something violent to others than the person described in the major depression vignette (B=.52, t=8.37, df=620, p<.001). The fourth model showed that the interaction between race and type of disorder was not significant ( Table 1 ).

Blame

As shown in Table 2 , the first model showed that African Americans were less likely than Caucasians to blame individuals with mental illness for violent acts (B=-.23, t=-2.33, df=632, p<.05). The second model showed that the effect of race remained significant even with sociodemographic controls (B=-.25, t=-2.51, df=624, p<.05). Respondents who were younger (B=-.01, t=-5.34, df=624, p<.001), more conservative (B=.07, t=2.47, df=624, p<.05), and Protestant (B=-.30, t=-3.11, df=624, p<.01) were more likely to blame individuals with mental illness for violent acts. The third model indicated that respondents were less likely to believe that the person with schizophrenia instead of the person with major depression should be blamed for violent behavior (B=-.23, t=-3.82, df=623, p<.001). The fourth model showed that the interaction between race and vignette type was not significant ( Table 2 ).

|

Punishment

As indicated in Table 3 , the first model showed that African Americans were less likely than Caucasians to believe that individuals with mental illness should be punished for violent acts (B=-.52, t=-3.91, df=652, p<.001). The second model showed that the effect of race remained significant even with sociodemographic controls (B=-.53, t=-3.79, df=644, p<.001). Respondents who were younger (B=-.01, t=-5.10, df=644, p<.001) and more conservative (B=.18, t=4.44, df=644, p<.001) and who had higher incomes (B=.10, t=2.75, df=644, p<.01) were more likely to believe in punishment. The third model indicated that respondents were less likely to believe that the person with schizophrenia should be punished for violent behavior compared with the person with major depression (B=-.26, t=-3.25, df=643, p<.01). The fourth model showed that the interaction between race and vignette type was not significant ( Table 3 ).

Discussion

We examined differences between African Americans and Caucasians in stigmatizing attitudes toward individuals with mental illness. Consistent with previous research conducted by Whaley ( 18 ), our results showed that African Americans were more likely to believe that people with mental illness would do something violent to others. This robust finding could not be explained by sociodemographic differences between the two groups. At the same time, the results also revealed a more complex picture with regard to stigma. Our findings indicated that even though African Americans were more likely than Caucasians to believe individuals with mental illness would be violent, they were less likely to believe that these individuals should be blamed and punished if they were violent. African Americans were more lenient and less punishing in their views on how people with mental illness should be treated, thus attributing less stigma with respect to these more behaviorally oriented outcomes that better capture what the general public would actually do if an individual with mental illness were violent.

We also found that younger and more conservative respondents were more likely to believe that individuals with mental illness should be blamed and punished for violent behavior. In addition, Protestants were more likely than people of other religions to blame mentally ill individuals for becoming violent, and respondents with higher incomes were more likely to believe that individuals with mental illness who committed violent acts should be punished. However, these sociodemographic and attitudinal effects did not explain the difference in blame and punishment between African Americans and Caucasians. We also found that, in general, respondents believed that individuals with schizophrenia were more likely to be violent than individuals with major depressive disorder. However, respondents were less likely to believe individuals with schizophrenia should be blamed and punished if they committed a violent act.

This study has strengths that add to the literature, but it is not without limitations. First, two inherent limitations of the vignette experiment should be noted. The vignettes describe specific scenarios, necessarily limiting our ability to generalize to all cases of mental illness. In addition, respondents were confronted with a hypothetical situation, and only behavioral intentions, not actual behaviors, were measured. It is possible that real-life reactions to real people would differ from those that were observed in the vignette experiment. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to suppose that people's stated feelings about perceptions of danger and attitudes about blame and punishment would have some bearing on their actual behavior.

Second, it is possible that matching the vignette subject's race with the respondent's race may have confounded the main result. African Americans have been negatively stereotyped in the media as people to be feared and as more violent than people of other racial and ethnic groups ( 20 , 21 ). Thus African-American respondents may have been more likely to expect violence because the person described was African American. This possibility was empirically tested by examining whether African Americans also perceived more violence among the subjects described in physical illness vignettes. We conducted a one-way analysis of variance and found no significant differences between African Americans and Caucasians in perceptions that a person with a physical illness would be violent. Therefore, the increased perceptions of violence found among African Americans toward people with mental illness cannot be attributed to a general tendency to view African Americans as more violent. Thus, although we recognize the ethnic matching of vignette and respondent as a possible limitation, the foregoing considerations led us to strongly doubt that this methodological feature had an important impact on our results.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate the importance of addressing racial differences when investigating stigma and mental illness. Not only did we find robust differences between African Americans and Caucasians on specific stigmatizing attitudes, we also found that these racial differences in stigma are not homogeneously negative among either group. Thus the hypothesis that African Americans are more hesitant to seek mental health care because they universally hold more negative stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness needs to be reexamined and refined. The African Americans in our sample were more likely than Caucasians to endorse perceptions of dangerousness but were less likely to endorse harsher critical attitudes regarding blame and punishment.

Increased stigma among African Americans and other racial minority groups has commonly been cited in the literature as an explanation for lower rates of seeking treatment for mental illness among these groups. To some extent, our findings challenge this argument. We found less blame and punishing attitudes toward people with mental illness among African Americans. Thus these types of stigmatizing attitudes could not explain lower rates of seeking treatment among African Americans. There may be something specific about the fear of being labeled as violent that motivates African Americans to avoid the label of mental illness associated with receiving mental health care as opposed to the fear of being blamed or punished for their behavior.

Another possible explanation for this interesting pattern of findings is related to attribution theory. Attribution theory suggests that negative behaviors, such as violence, may lead to more sympathetic responses toward people with mental illness if the violence is viewed as out of the individual's control ( 22 , 23 ). It is possible that among African Americans, a mental illness label elicits a more sympathetic response even though the label is associated with more violence. In fact it could be that an increased perception of violence is part of a more general perception that absolves a mentally ill person of responsibility for his or her illness-related behavior. Another possible explanation for this pattern of findings is that African Americans might be less likely to blame and punish people with mental illnesses who may have been violent because they can more readily sympathize with the experience of being stereotyped as violent. Future research should empirically examine these possible explanations. For example, studies should include questions about whether behaviors are in the control of an individual with mental illness.

Even though African Americans were more likely to endorse stereotypes about individuals with mental illness, they appeared to be more sympathetic and understanding in their views about how these people should be treated. One might wonder whether these racial differences depend on the type of mental illness being considered. We found no evidence for this. The increased leniency was evident for both schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. It is possible that this increased leniency among African Americans toward people with mental illness reflects a cultural variation that should be considered a strength that can be expanded upon in stigma-reducing interventions targeted to the African-American community.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01-HG01859 from the National Human Genome Research Institute, grant K02-MH065330 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. Parts of this article were presented at the annual meeting of the Winter Roundtable on Cultural Psychology and Education, held February 18-20, 2005, in New York City and at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, held August 17-21, 2005, in Washington, D.C.

1. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. Rockville, Md, Office of the Surgeon General, 2001Google Scholar

2. Cooper A, Corrigan PW, Watson AC: Mental illness stigma and care seeking. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:339-341, 2003Google Scholar

3. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77-84, 2002Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, et al: The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness. Health Services Research 36:987-1007, 2001Google Scholar

6. Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, et al: Adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatric Services 52:1627-1632, 2001Google Scholar

7. Snowden LR: African American service use for mental health problems. Journal of Community Psychology 27:303-313, 1999Google Scholar

8. Sirey HA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services 52:1615-1620, 2001Google Scholar

9. Sirey HA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al: Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:479-481, 2001Google Scholar

10. Corrigan P: How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist 59:614-625, 2004Google Scholar

11. Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, et al: Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 12:431-438, 1997Google Scholar

12. Silva de Crane R, Spielberger CD: Attitudes of Hispanics, Blacks, and Caucasian university students toward mental illness. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 3:241-255, 1981Google Scholar

13. Sanders Thompson VL, Bazile A, Akbar M: African Americans' perceptions of psychotherapy and psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 35:19-26, 2004Google Scholar

14. Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, et al: The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. American Journal of Sociology 92:1461-1500, 1987Google Scholar

15. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al: Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health 89:1328-1333, 1999Google Scholar

16. Phelan JC, Link BG, Stueve A, et al: Public conceptions of mental health in 1950 and 1996: what is mental illness and is it to be feared? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:188-207, 2000Google Scholar

17. Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, et al: The public's view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems. American Journal of Public Health 89:1339-1345, 1999Google Scholar

18. Whaley A: Ethnic and racial differences in perceptions of dangerousness of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:1328-1330, 1997Google Scholar

19. Allison PD: Missing Data. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage Publications, 2002Google Scholar

20. Entman RM, Rojecki A: The Black Image in the White Mind: Media and Race in America. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2001Google Scholar

21. Stark E: The myth of Black violence. Social Work 38:485-490, 1993Google Scholar

22. Weiner B: On sin versus sickness, a theory of perceived responsibility and social motivation. American Psychologist 48:957-965, 1993Google Scholar

23. Weiner B: Judgments of Responsibility: A Foundation for a Theory of Social Conduct. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar