Assessing Gaps Between Policy and Practice in Medicaid Disenrollment of Jail Detainees With Severe Mental Illness

Medicaid plays a significant role in ensuring that people with severe mental illness receive mental health services, and it has become the single largest payer for such services, representing about 20 percent of the U.S. total spending for mental health care in 1997. Moreover, spending on mental health and substance use disorders accounted for approximately 10 percent of overall growth in Medicaid spending between 1987 and 1997 ( 1 ).

In addition to receiving treatment from the community mental health services system, in which Medicaid is the main payer, persons with severe mental illness can often be involved with local criminal justice systems. Current best estimates suggest that about 8 percent of all jail detainees (gender adjusted) have a severe mental illness ( 2 , 3 , 4 ). With annual admissions to U.S. jails now numbering about 12.5 million (Karberg J, personal communication, 2004), about one million persons with severe mental illness are admitted annually to our nation's jails. Although many are enrolled in Medicaid upon jail entry, Medicaid does not pay for services provided to individuals during incarceration.

Medicaid benefits are crucial at the point of release from jail. Detainees with severe mental illness must be able to access mental health and substance abuse services upon their release, and as we showed in another article in this issue of Psychiatric Services ( 5 ), in many cases, having Medicaid at that time is a distinct advantage in accessing services.

Nationally and locally, there is concern that persons with severe mental illness lose their Medicaid benefits during incarceration ( 6 , 7 , 8 ). Much of this concern has been precipitated by the Social Security Administration (SSA) program that rewards jails with up to $400 for reporting an incarcerated person receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) ( 6 ). According to a General Accounting Office report, 3,115 correctional facilities signed agreements to report such persons, which resulted in 39,137 SSI benefit suspensions and a cost savings of $37.6 million in inappropriate SSI payments ( 9 ).

The stated intent of the SSA program is to prevent the fraudulent receipt of monthly income benefits while an individual is incarcerated. SSA uses a full calendar month cut-off—the so-called inmate exclusion rule—whereby persons on SSA benefits who exceed this interval may be suspended from SSI and SSDI. For adult males (the largest proportion of jail detainees), Medicaid enrollment is tied to SSA disability benefits. So if income benefits are terminated on a large scale, then medical benefits would also be disrupted when vulnerable populations are detained in jail. Although individuals who are disenrolled may apply for reenrollment after release, eligibility determinations frequently take a significant amount of time, and by law the process can extend as long as 90 days ( 10 ). The loss of Medicaid could result in significant cost shifts and increased burden on jail services, local mental health programs, and state hospitals, as well as state prisons.

It is important to emphasize the distinction between jails and prisons. Jails are short-stay, locally operated facilities that serve as adjuncts of the courts to detain persons awaiting trial and to incarcerate those sentenced to a year or less on misdemeanor offenses. As such, jails are the front door to the criminal justice system; everyone who is arrested spends some time in jail waiting for processing. Prisons, on the other hand, are the back door to the system. They are federal- or state-operated, long-stay facilities (about 5.5 years on average) for those convicted of felony offenses. Because of the prolonged stays, virtually all prisoners will lose their Social Security and Medicaid benefits. Despite concerns expressed by advocacy groups ( 6 , 7 , 8 ), little empirical evidence is available to assess whether and how often Medicaid disenrollment actually occurs for jail detainees with severe mental illness.

To address this gap, we report findings from a survey of state Medicaid agency directors who identified disenrollment policies for jail detainees and from an analysis of administrative data from two large urban counties that document the extent to which jail detainees with severe mental illness were actually disenrolled.

Methods

Medicaid director survey

The Council of State Governments (CSG) in 2000 surveyed how states were implementing the inmate exclusion clause of the SSA for jail detainees with severe mental illness ( 8 ). Surveys were sent to Medicaid officials in all 50 states, five territories, and the District of Columbia, which yielded a response rate of 95 percent (Ohio, Tennessee, and the District of Columbia did not respond).

Although most of the data regarding state implementation of policies related to Medicaid enrollment and mentally ill detainees came from the CSG survey, the data from the survey were supplemented with information derived from a series of in-person and telephone interviews with jail officials, Medicaid officials, Social Security Administration staff, and other researchers in order to identify some of the administrative practices that have been implemented to carry out the policies reported by the CSG. More specifically, respondents were asked how a Medicaid agency learns about a Medicaid-enrolled detainee, whether the agency takes action, and what action the agency takes, as well as about information about other agencies that may be involved. In total, 30 people were questioned about various activities related to Medicaid eligibility and enrollment for detainees with severe mental illness. Officials and experts in the field were identified by a co-author of this paper, and then individuals who were interviewed were asked to name others who might be able to provide more information.

Administrative data

To address our study's objectives concerning Medicaid disenrollment, a prospective cohort design was implemented by using linked, administrative data from two large U.S. counties—Pinellas County (Clearwater and St. Petersburg), Florida, and King County (Seattle), Washington. The following data were accessed: Medicaid enrollment records, jail detention records, inpatient and outpatient mental health utilization records, and inpatient and outpatient substance abuse treatment records. Further details on the linkage procedures used in King and Pinellas Counties can be obtained from the lead author.

The demographic and jail profiles of the two counties are generally quite similar. The year 2000 population in King County was about twice as large as that in Pinellas County (1.74 million compared with .92 million) and had a 43 percent higher median income ($53,157 compared with $37,111). In 2000 both counties were closely ranked with regard to the size of their jail populations—33rd and 34th nationally ( 11 ). The annual incarceration rate per 100,000 was about 37 percent larger in Pinellas County (4,818 compared with 3,511).

Sample

Samples included all persons with serious mental illness enrolled in Medicaid and detained in jail within a two-year study interval—October 1998 through September 2000 in Pinellas County and October 1996 through September 1998 in King County. Medicaid enrollment was defined as having an active, open Medicaid case file, and eligibility for inclusion in the study was defined as being enrolled during any part of the study.

The logic of sample enumeration was the same for each county, but data sources varied somewhat. First, in both counties, samples of persons with severe mental illness were identified. For Pinellas County, a person with severe mental illness was defined as anyone who had at least one Medicaid claim that was associated with one of the following DSM-IV diagnosis codes: schizophrenia (295), affective disorders (296, except for 296.1, single-episode depression), unspecified psychotic disorder (298.9), and delusional disorder (297.10). For King County, because of the unavailability of Medicaid claims, any person who had a community mental health service associated with one of the diagnosis codes was identified as someone with severe mental illness. Next, samples were matched to incarceration records from their respective county jails.

This sampling strategy yielded 1,816 persons and 4,482 detentions for King County and 1,210 persons and 2,878 detentions for Pinellas County. The analyses below are based on detentions rather than persons so that each detention is treated as a separate event. Disenrollment from Medicaid can occur during any one jail stay, so we wanted to count the total possible events that occurred during the study intervals. As a check, we examined the number of persons involved in all instances in which disenrollment occurred and found the counts of detainees and persons to be nearly identical. In King County, for example, a total of 94 detainees were disenrolled during the study period; 90 of these detainees were distinct persons, and four were accounted for by two additional persons who had duplicate detentions.

The mean±SD age of the sample in King County was 35±9.1 years, and it was 35±9.3 years in Pinellas County. Males constituted a larger percentage of the King County sample (2,986 detentions in King County, or 67 percent, compared with 1,662 detentions in Pinellas County, or 58 percent); both samples were predominately white (60 to 68 percent) with King County having a greater proportion of blacks (1,610 detentions in King County, or 36 percent, compared with 650 detentions in Pinellas County, or 23 percent). The predominant diagnosis in both samples was affective disorders (52 to 59 percent), with Pinellas County having a greater percentage of persons with schizophrenia (1,281 detentions in Pinellas County, or 45 percent, compared with 1,403 detentions in King County, or 31 percent) and King County having a greater percentage of persons with unspecified psychotic disorders (398 detentions in King County, or 9 percent, compared with 91 detentions in Pinellas County, or 3 percent).

Cohorts

To examine the occurrence and impact of Medicaid disenrollment during incarceration, the samples were separated into cohorts defined by Medicaid enrollment status at jail entry and release. Four cohorts were enumerated: cohort 1, Medicaid at jail entry and at jail release; cohort 2, Medicaid at jail entry and no Medicaid at jail release; cohort 3, no Medicaid at jail entry and Medicaid at jail release; and cohort 4, no Medicaid at jail entry and none at jail release. The first two cohorts are of particular interest—detentions characterized by continuous Medicaid enrollment (cohort 1) and those disenrolled (cohort 2) while incarcerated. The rate of disenrollment was calculated by dividing the number of detentions in cohort 2 by the total number of detentions that represented persons who had Medicaid upon jail entry (cohort 2/[cohort 1+cohort 2]).

Notably, all persons in this study were enrolled in Medicaid at some time during study intervals. Detentions in cohorts 3 and 4 represented persons who either lost enrollment or had not yet been enrolled on the date of jail entry. This sampling design thereby controls for Medicaid eligibility and helps to ensure comparability among the four cohorts with respect to disability status and financial need. A total of 1,581 persons (87 percent) in the King County sample and 955 (79 percent) in the Pinellas County sample were on SSI or SSDI.

The study protocol was reviewed for human subjects' protection and approved by institutional review boards at each investigator's home institution.

Results

Medicaid director survey

According to the Medicaid director survey, more than 90 percent of states have policies requiring Medicaid termination upon an incarceration, but a closer examination of policies and administrative procedures revealed significant variability. As shown in the box on the next page, 33 of 48 states (69 percent) have policies to terminate enrollment, and another five states (10 percent) reported that enrollment was terminated "with notice." States varied with respect to notice periods.

Three states (6 percent) reported terminating Medicaid benefits for inmates "after verification." This type of verification is likely a reference to the completion of an ex parte review, in which Medicaid agencies can review an individual's ongoing eligibility status without requiring any new supporting documentation. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has indicated that enrollment of an individual who is incarcerated should be terminated only after an ex parte review ( 12 ). Only one state, South Carolina, reported implementing the administrative action that providers and advocates have been promoting—the simple suspension of federal claims pending an inmate's release.

Medicaid officials were also asked how they learned that someone was incarcerated. Only 15 of the 48 states (31 percent) reported electronic data exchanges between agencies, some of which were explicitly done with the SSA rather than the criminal justice agency. Respondents in 22 states (46 percent) indicated that they learned of an incarceration through a "contact" with another public agency but did not explicitly state that it was an electronic data exchange. In seven states (15 percent), the Medicaid agencies specifically reported that they received information from the SSA and not the criminal justice agency. Another 29 states (60 percent) reported receiving information through family or other informal mechanisms, such as returned mail or arrest notices in the newspaper. For 11 of those states (23 percent), the informal exchange was the sole source of information. In these states terminations based on incarceration are probably not implemented on a systematic basis.

Disenrollment

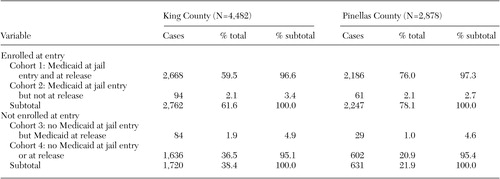

Table 1 presents the results from the disenrollment analyses for King and Pinellas Counties. Overall, 2,762 of 4,482 detentions (62 percent) in King County and 2,247 of 2,878 (78 percent) in Pinellas County were characterized as Medicaid-enrolled at jail entry. The key group of interest, cohort 2 (detentions characterized as having Medicaid at jail entry but not at release) was surprisingly small in each county—only 94 detentions (3.4 percent of those enrolled at jail entry) in King County and 61 (2.7 percent of those enrolled at jail entry) in Pinellas County. In both counties, in 97 percent of the detentions, persons who had Medicaid at entry also had it upon release. So although Medicaid officials in these two states reported that all such cases are terminated, only a few were actually disenrolled.

|

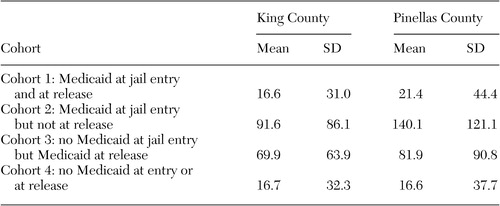

Who was disenrolled? Closer inspection of the data suggested that a change in Medicaid status, either losing it or gaining it, was more likely as length of incarceration increased ( Table 2 ). Cohorts 1 and 4, in which Medicaid status was not changed during incarceration, had relatively short stays (means of 16.6 and 16.7 days, respectively, in King County and means of 21.4 and 16.6 days, respectively, in Pinellas County). Cohorts 2 and 3, in which Medicaid status changed (in both directions), experienced much longer lengths of stay (means of 91.6 and 69.9 days, respectively, in King County and 140.1 and 81.9 days, respectively, in Pinellas County).

|

Discussion

Contrary to widespread concerns, these findings from two large metropolitan jail systems suggest that jail detention had little impact on the Medicaid status of detainees with severe mental illness; in fact, most cycled in and out of jail so rapidly that their Medicaid benefits were not disrupted. Fully 97 percent of those with Medicaid at jail entry were released with Medicaid intact after being detained, on average, approximately two weeks (16.6 days) in King County and three weeks (21.4 days) in Pinellas County. Most of the detentions in this study did not exceed one calendar month. Because the 30-day Social Security cutoff point was not exceeded in these instances, Medicaid benefits were not affected. It was the relatively small number of detainees with severe mental illness in cohort 2 who were incarcerated an average of 92 days in King County and 140 days in Pinellas County who were at the greatest risk of losing their benefits.

These findings suggest that the gap is substantial between stated Medicaid disenrollment policy and actual practice, at least in these two jail systems. Whereas survey results indicate that nearly all states disenroll jailed Medicaid beneficiaries, this actually happened for only about 3 percent of the detainees with severe mental illness who had Medicaid at jail entry. Thus concerns about rampant Medicaid disenrollment of detainees with severe mental illness may be exaggerated.

Is the policy gap real, and if so, why is there a big discrepancy between policy and practice? Several factors are likely involved. First, length of incarceration matters. As these findings make clear, on average, most detainees with severe mental illness were released from these jails within a few weeks. Only a very small minority that stayed upwards of three months were likely to lose Medicaid benefits.

Another reason for the discrepancy may be delays in administrative processing between agencies. For disenrollment to occur, notice of a beneficiary's incarceration would have to work its way through the system, and only those who were in jail for longer periods would still be in jail by the time the information about their incarceration reached the Medicaid administrators who would terminate enrollment. In addition, for those whose eligibility was related to their SSI status, their Medicaid eligibility would likely not have been called into question until after a full calendar month of incarceration, when their SSI could be legally suspended.

A third reason for this discrepancy is related to what Cohen and Cohen ( 13 ) have described as the "clinician's illusion," although in this case it's more aptly described as the "administrator's illusion." Namely, most administrators, whether in jails or Medicaid agencies, may not have an accurate sense of the true count of persons enrolled in Medicaid who are entering jail. When asked to respond about the rate of disenrollment, their perceived count was biased toward cases with longer jail stays that have a higher likelihood of disenrollment and tended to overlook a large majority of those with shorter stays who have a much lower likelihood of disenrollment. As a result, respondents typically focused on the few cases in which disenrollment occurs and mistakenly assume that their number is close to the full population. So they readily report, "Yes, we disenroll all such persons."

One strength of this study is its multiyear, longitudinal design. However, because this study was based on a sample of only two jails, the extent to which these findings generalize to other communities and jails is uncertain. Because length of stay appears to be the main determinant of Medicaid disenrollment while in jail, jurisdictions that have much longer average lengths of stay for severely mentally ill detainees than King or Pinellas Counties may have much larger Medicaid disenrollment rates.

Unfortunately, there are no national data on jail detainees with mental illness so the true national disenrollment rate is unknown. However, mega-jails in the largest U.S. cities may have significantly different experiences than those reported here. The Cook County Jail in Chicago, for example, has a daily census of about 11,000 detainees who are detained an average of six months, and severely mentally ill detainees stay even longer (Alaimo C, personal communication, 2005). In such settings, Medicaid disenrollment for persons with severe mental illness is likely to occur more regularly. Perhaps what is most generalizable from this study is the link between length of jail stay and Medicaid disenrollment. One key to understanding jail stays in any jurisdiction is how efficiently the court system operates. Regardless of population size, in communities in which the courts are greatly backlogged, jail stays will be longer and Medicaid disenrollment more pronounced.

Another potential limitation of this study is that it was based on administrative data. Underreporting in one or more information systems could lead to problems in matching individuals across county mental health, Medicaid, and county jail systems. Also, lacking an independent measure of mental health status, we had to rely on Medicaid claims (Pinellas) or the county mental health system (King) to identify persons who had a qualifying diagnosis. Thus persons with severe mental illness who entered the jail without service contacts in these data systems would not be counted and neither would those who had service contacts only from private physicians, state hospitals, or local community hospitals. The two-year study interval helped to minimize these potential biases, but they were not eliminated.

The data considered in this study are several years old now (1996 to 2000). The past few years have witnessed a general economic decline that has adversely affected state and county budgets. These revenue short-falls, in turn, have squeezed Medicaid budgets and led to sharp reductions in Medicaid eligibility and services in many states ( 14 , 15 , 16 ). To the extent that these reductions disproportionately affected persons with a severe mental illness, the results reported here may underestimate current rates of Medicaid disenrollment in jail. However, there is no evidence that these policy changes have increased jail stays for this population, so the risk of having Medicaid terminated while detained in jail would likely have remained unchanged.

Finally, one important caveat should be stressed—that is, these findings should not be generalized to state or federal prisons. As noted earlier, jails are short-stay facilities, whereas prisons are long-stay facilities. Because of the differences between the two institutions, the probabilities of losing Medicaid and other Social Security benefits are poles apart. It is likely that all prisoners will lose their benefits before release, whereas most jail detainees will not, which means that individuals with severe mental illness who end up in prison will need considerable help if they are to regain lost benefits before their return to the community. Moreover, except for the very largest jail systems, facility-based benefit restoration programs may make more sense for prisons than for jails. At the local community level, the better strategy might be to invest scarce resources into diverting persons with severe mental illness from jails into community-based treatment programs, where Medicaid benefits can be more easily accessed, retained, and restored.

Conclusions

This research also confirms several principles of public administration that most people agree with in theory but few policy makers act on. First, anecdotal evidence should not drive policy, and assumptions that practice mirrors policy can be erroneous. In fact, we found inconsistencies and significant gaps between what is anecdotally reported about policies and what actually happens with Medicaid disenrollment. Second, policy incentives often don't generalize across systems. Although benefit disenrollment might save money for SSA and state Medicaid programs, it has the potential to undermine state and local mental health policies about promoting care in the least restrictive settings that enhance the ability of people with severe mental illness to live stable and productive lives in the community.

One of the little recognized developments over the past 50 years is the shrinkage of the public mental health system ( 17 ). Today, many persons with severe mental illness who at an earlier time would be residents of state mental hospitals are found in a variety of sectors outside the public mental health system—jails, public housing, Medicaid, vocational rehabilitation, and social welfare—where they fall under policies that do not recognize their special needs. This fact underscores one of the major challenges mental health policy makers now face—how to overcome competing incentives and the lack of intersystem collaboration in the wider human services arena where persons with mental illness can now be found. One clear implication of the results is that public mental health authorities must do a better job of participating in policy making and rule making concerning Medicaid and SSI benefits for persons with severe mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The research upon which this report is based was supported by grant funding from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation's Mental Health Policy Research Network and from grant MH-63883 from the National Institute of Mental Health. For assistance in assembling the administrative data for this study the authors thank the Pinellas County Data Collaborative; the Pinellas County Mental Health and Substance Abuse Leadership Group; Armstrong Information Solutions; the King County Division of Mental Health, Chemical Abuse, and Dependency Services; the King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention; the King County Department of Public Health; the Washington State Department of Mental Health; the Divisions of Medical Assistance and Alcohol and Substance Abuse of the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services; and the Washington State Department of Health.

1. Frank R, Goldman H, Hogan M: Medicaid and mental health: be careful what you ask for. Health Affairs 22(1):101-113, 2003Google Scholar

2. Teplin L: The prevalence of severe mental disorder among male urban jail detainees: comparison with the epidemiologic catchment area program. American Journal of Public Health 80:663-669, 1990Google Scholar

3. Teplin L, Abram K, McClelland G: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women: I. Pretrial jail detainees. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:505-512, 1996Google Scholar

4. Subcommittee on Criminal Justice: Background Paper. DHHS pub no 8MA-04-3880. Rockville, Md, New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2004Google Scholar

5. Morrissey JP, Steadman HJ, Dalton KM, et al: Medicaid enrollment and mental health service use following release of jail detainees with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 57:809-815, 2006Google Scholar

6. For People With Serious Mental Illnesses: Finding the Key to Successful Transition From Jail to Community: An Explanation of Federal Medicaid and Disability Program Rules. Washington, DC, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, 2001Google Scholar

7. Maintaining Medicaid Benefits for Jail Detainees with Co-occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders. Fact Sheet Series. Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center, 2001Google Scholar

8. Access to Benefits for Offenders With Mental Illness Leaving State Prisons: State and Federal Policy Forum. New York, Council of State Governments, 2004. Available at www.reentrypolicy.org/rp/main.aspx?dbID=DBFederalBenefits432Google Scholar

9. Supplemental Security Income: Incentive Payments have Reduced Benefit Overpayments to Prisoners. Washington, DC, United States General Accounting Office, 1999Google Scholar

10. Timely Determination of Medicaid Eligibility: 42 CFR 435.911, 2002Google Scholar

11. Beck A, Karberg J: Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2000, in Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. NCJ 185989. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 2001Google Scholar

12. Thompson T: Letters From DHHS Secretary Thompson to Congressman Charles Rangel, Oct 1, 2001Google Scholar

13. Cohen P, Cohen J: The clinician's illusion. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:1178-1182, 1984Google Scholar

14. Ku L, Rothbaum E: Many States are Considering Medicaid Cutbacks in the Midst of the Economic Downturn. Washington, DC, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2001. Available at www.cbpp.org/10-24-01health.htmGoogle Scholar

15. Balit M, Burgess L, Roddy T: State Budget Cuts and Medicaid Managed Care: Case Studies of Four States. Portland, Maine, National Academy for State Health Policy, 2004. Available at www.nashp.org/files/mmc63budgetcutsinfourstates.pdfGoogle Scholar

16. The Continuing Medicaid Budget Challenge: State Medicaid Spending Growth and Cost Containment in Fiscal Years 2004 and 2005: Results of a 50 State Survey. Washington, DC, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004Google Scholar

17. Frank R, Glied S: Better But Not Well: Mental Health Policy Over the Past Fifty Years. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006Google Scholar