"Difficult Patients" in Mental Health Care: A Review

The "difficult patient" is a well-known figure in everyday mental health care yet is underrepresented in research reports. The adjective difficult often refers to the lack of cooperation between patient and professional: although the patient seeks help and care, the patient does not readily accept what is offered. The frequent use of the term seems to indicate a well-known and well-distinguished group of patients. This is not the case, however: difficult patients are hard to describe and characterize as a group. Since the first attempt over 25 years ago to empirically assess characteristics of difficult patients ( 1 ), numerous nonempirical and few empirical articles have been published. This review aims to highlight important findings that may be used in daily practice.

Methods

For this literature review, we conducted a search of the MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases for articles published in English between 1979 and 2004 about patients between 18 and 65 years of age. The title words "difficult patient" or "problem patient" were combined (with Boolean "and") with keywords "mental disorders" and the following terms (with Boolean "or"): "mental health services," "psychiatric hospitals," "treatment," "psychotherapy" "therapeutic alliance," "therapeutic processes," "physician-patient relations," or "nurse-patient relations." Selection took place according to various criteria. An article was excluded when it did not have "difficult patient" as its main subject, it primarily focused on a specified non-mental health setting (for example, a surgical ward of a general hospital), it related difficulty only to one specific diagnostic category (for example, difficulties in the treatment of eating disorders), or it presented a case study without any reflection or theory building apart from the particular case.

Cross-references were used extensively to find additional publications. In doing so, four frequently cited articles published earlier than the studies within the range of the database search ( 14 , 16 , 32 , 33 , discussed below) were assessed as relevant for this literature review. In all, 94 titles were included.

Results

Characteristics

Most data came from quantitative studies published before 1991 ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) that, except for two studies ( 1 , 7 ), did not provide control groups. In these studies, most of the difficult patients were between 26 and 32 years of age, whereas control patients were either of the same age ( 1 ) or somewhat older ( 7 ). More than control patients, difficult patients were unemployed and poorly educated. In most studies, difficult patients were predominantly men (between 60 and 68 percent). Diagnoses of psychotic and personality disorders were the most common. Prevalence of the former varied (19 to 44 percent), and prevalence of the latter was consistently high (32 to 46 percent) across all studies. Mood disorders (8 to 24 percent) and other disorders (4 to 16 percent) were less frequently found. Data on comorbidity of DSM axis I and II disorders were absent across all studies.

Together, the studies refer to four dimensions of difficult behaviors: withdrawn and hard to reach, demanding and claiming, attention seeking and manipulating, and aggressive and dangerous. The first category is found mostly among patients with psychotic disorders, the second and third mostly among those with personality disorders, and the fourth appears with both diagnostic groups. Estimates of relative or absolute frequency of difficult patients were available from only one study, in which 6 percent of all 445 inpatients in a psychiatric hospital were considered difficult by at least two members of an inpatient nursing team ( 7 ).

Difficult patients appear in both inpatient ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ) and outpatient ( 1 , 9 ) settings, yet no data were found on the prevalence of difficult patients in these subgroups, except for the study previously mentioned. One study ( 9 ) found a high correlation between difficult patients, the number of hospital admissions, and inpatient days, which indicated a higher prevalence of difficult patients among inpatients. All studies considered psychiatric treatment centers at general psychiatric hospitals and outpatient clinics.

Most difficult patients are offered a pragmatic, eclectic form of psychiatric treatment. Because of their easy accessibility, both financially and physically, general mental health centers tend to attract a greater number of difficult patients, especially when emergency care is delivered ( 1 ). Neill ( 1 ) also found significant differences regarding a treatment plan and a primary caregiver. All control patients had both, whereas the difficult patients had neither. Difficult patients' files were updated less thoroughly, and communication between professionals of different treatment programs about these patients was minimal ( 1 ).

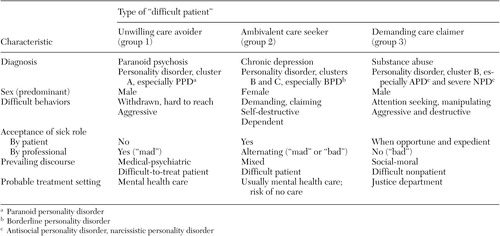

From the data reviewed, we hypothesize three subgroups of difficult patients, as presented in Table 1 . In this scheme the first group of difficult patients, care avoiders, consists of severely psychotic patients who do not consider themselves ill and who view mental health care as interference. The second group, care seekers, consists of patients who have chronic mental illness yet have difficulty maintaining a steady relationship with caregivers. The third group, care claimers, consists of patients who do not need long-term care but need some short-term benefit that mental health care offers, such as housing, medication, or a declaration of incompetence.

|

Theoretical explanations

Individual factors . Four major theoretical explanations were frequently identified in the articles reviewed: chronicity, dependency, character pathology, and lack of reflective capabilities.

The first, chronicity, considers the course of the difficult patient's psychiatric disorder, which almost always is chronic and renders the patient dependent on mental health institutions ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). Chronic patients experience problems that are difficult to resolve by the psychiatric system, which leads to labeling these patients as problematic and difficult. Although chronicity of a mental disorder is a patient's personal matter, chronicity is also considered problematic for mental health professionals: "the sufferer who frustrates a keen therapist by failing to improve is always in danger of meeting primitive behavior disguised as treatment" ( 14 ). Apart from being one explanation for patients' difficulty, chronicity induces specific responses by the psychiatric treatment system and is covered in more detail later.

Dependency on care is a second reason for perceived patient difficulty. Severe, unmet dependency needs lead the patient to project a lack of stable self and basic trust onto the caregiver ( 1 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ). The caregiver then experiences the patient as demanding and claiming, which makes the interpersonal contact difficult. Underlying the difficult behaviors of so-called hateful patients there seems to be a strong need for dependency ( 16 ). These patients, who exhibit clinging, denying, entitled, or self-destructive behaviors, all have problems in tolerating a normal dependency ( 18 ). In qualitative interviews with nurses, a clear difference was found between "good" and "difficult" dependent patients ( 19 ). Good patients were described as reasonable and thankful; difficult patients were described as unreasonable, selfish, and not able to appreciate the value of given care. Power struggles arose easily with the latter category ( 20 ). The relationship with the mental health professional becomes so important for many difficult patients that terminating it seems impossible, both for patient and professional ( 21 ).

A third, psychodynamic view is that difficult patients have character pathology. Specifically, paranoid, borderline, narcissistic, and antisocial ( 22 , 23 ) personality disorders would make for difficult patients. Psychiatrists mentioned the diagnosis borderline personality disorder up to four times more often than any other diagnosis when asked about characteristics of difficult patients. Less frequent were paranoid, antisocial, sociopathic, obsessive, and narcissistic disorders ( 24 ). According to several authors ( 10 , 18 , 25 ), almost all difficult patients have a so-called borderline personality organization, which would explain why so many difficult patients have a highly ambivalent relationship with mental health care. People with this kind of personality organization perceive reality accurately yet feel overwhelmed by it, resulting in intense feelings of suffering and a need to seek help. In combination with so-called primitive defenses, such as splitting, idealizing, and projective identification, this lack of a clear self is considered a major source of the often confusing and negative interactions with professionals ( 18 , 26 , 27 , 28 ).

The fourth explanation for patients' being difficult is related to their perceived lack of reflective capacities. Reflection lies at the core of most psychotherapies; therefore, an incapability to reflect will easily turn the patient into a not-so-suitable (difficult) patient. People who are not securely attached in their younger days especially seem to lack these reflective or "mentalizing" capacities ( 29 ). This insecure attachment may have many causes, one of which is trauma ( 30 ), and easily creates problems in interpersonal relations, including those with caregivers ( 28 , 31 ).

Interpersonal factors. Some authors emphasized that it is not the patient but the therapeutic relationship that is difficult, thus taking the blame off the patient and situating problems in an interpersonal context. Traditional concepts of transference and countertransference are often used in this context, yet in a broader sense than in classic psychoanalytic theory. Countertransference in this context refers to the emotional struggles that emerge while working with difficult patients ( 6 ). Transference is defined as the unconscious feelings the patient has toward the therapist, based on earlier experiences in the patient's life (with therapists in general or with this particular therapist). Countertransference is, likewise, defined as the unconscious feelings the therapist has toward the patient, either based on the patient's present behavior or on the therapist's earlier professional and personal experiences. Examples of professionals' countertransference feelings toward difficult patients are anger, guilt, helplessness, powerlessness, dislike, and disappointment ( 3 , 4 , 14 , 16 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ).

Transference and countertransference issues between professionals and difficult patients are sometimes described in vivid detail ( 14 , 16 , 32 , 33 ). Although the concept of transference and countertransference is interpersonal, some authors maintained that the patient is responsible for evoking strong countertransference reactions ( 38 ). Some critics have indicated that early psychoanalysts who were unable to maintain a transference relation used the transference concept to blame the patient for therapy failure ( 39 , 40 ). Others assumed that the difficult patient exists only because of a lack of professionalism among caregivers. In other words, if all caregivers were properly psychoanalyzed, these interpersonal problems would not occur ( 41 ). Moreover, the transference relation is not a static one-way interaction but an intersubjective undertaking. In this view, two worlds need to meet, which is possible only if the therapist is able to put his or her own subjective views into perspective ( 42 ). A strong working alliance can be reached only by mutual understanding and giving meaning to difficult behaviors displayed by the patient and to the nature of the therapeutic relationship ( 43 ).

Countertransference in a multidisciplinary treatment setting has a different character, often strongly influenced by the so-called phenomenon of splitting. The difficult patient is considered a specialist in behaving differently with various team members, resulting in mutual disagreement ( 14 , 32 ). At the same time, the literature indicates that multidisciplinary teamwork with difficult patients is highly necessary, yet complex. Such teamwork leads to less trouble and fewer mistakes, because countertransference issues can be shared ( 44 ). Feelings that emerge in countertransference may lead to distinctive reactions—extra care on the one hand, active neglect on the other—and different professionals may experience distinctive feelings of countertransference ( 2 , 4 , 8 , 34 ). For example, physicians are challenged when medication fails, when patients manipulate, or when treatment is difficult ( 8 ). Nurses experience annoyance and anger when their caring attitude and competence are questioned ( 8 , 45 ). Both doctors and nurses get irritated when patients challenge their authority ( 1 , 46 ). Distinctions also have been noted between nurses' experiences on different types of psychiatric wards. Difficult behaviors were less easily interpreted as deliberate on wards with a psychodynamic orientation than on wards with a psychopharmacological orientation ( 47 ). Perceived difficulty differed between on-floor staff and off-floor staff. The former group experienced patients' difficulty more intensely because on-floor staff has closer physical and emotional interaction with them ( 48 ).

We found no studies that solely focused on the role of the professional. Yet some authors pointed out that some personality traits may increase the risk of difficult relationships with patients: a strong wish to cure, a great need to care, trouble with accepting defeat, and a confrontational and blaming attitude ( 14 , 33 , 49 , 50 ). Research on therapist variables that may account for good and bad treatment is still in its infancy ( 50 ). Given the previously discussed concept of "blaming the patient," such variables appear to be closely linked to patients' being called difficult.

Systemic and sociological factors. We next review the social environment as the major explanation for difficult patients. In general, authors who supported this view assumed that different forms of social judgment are responsible for patients being called difficult, including prejudice, labeling, and exclusion.

Prejudice takes place largely within the individual, although it often is influenced by societal beliefs. Psychiatric literature, especially, covers the negative effects of certain diagnoses on professionals' attitudes. In this review, these negative attitudes were found among psychiatrists working with patients with personality disorders ( 51 ) and among psychiatric nurses treating patients with borderline personality disorder ( 52 ). In these studies, professionals were asked to rate the difficulty of certain behaviors, dependent on the patient's diagnosis. Patients who were diagnosed as having borderline personality disorder were judged more negatively than were patients with other diagnoses—schizophrenia, for example—although their difficult behaviors, such as expressing emotional pain or not complying with the ward routine, were equal. This difference seems to imply that certain difficult diagnoses evoke negative reactions from professionals, independent of the patient's actual behavior. However, only a few articles on this matter were identified with the search terms used.

Labeling differs from prejudice in that it implies a form of action rather than a mere attitude. In group-therapeutic practice this phenomenon is specifically documented ( 53 ). It is not the diagnosis but deviancy from the particular group culture that leads to patients' being called difficult. This scapegoating may induce counter-therapeutic reactions by therapists ( 54 ), which refer to actions and reactions that reinforce the characterization of an individual as the difficult patient in a group. Intersubjective theory, in which patients' and professionals' beliefs and actions are considered as equally subjective input into the therapy process, highlights the risk of negative labeling of particular patients. This theory contrasts with some psychoanalytic views in which individual behaviors tied to specific diagnostic terms, such as borderline and narcissistic disorders, are held responsible for patients' difficulty in groups ( 55 , 56 ).

The phenomenon of labeling is especially present in nursing literature. Behavior that deviates from what may be expected in a specific context, such as a hospital ward, risks being labeled as difficult, sometimes resulting in withdrawal of necessary care ( 57 ). The difficult-patient label is easily and rapidly communicated among nurses and may lead to care of less quantity or quality ( 58 ). Some authors claimed that difficult patients are socially constructed in a complex web of social influences, including power, status, the management of uncertainty, and negotiation ( 59 ). Also the term stigma, first introduced by sociologist Erving Goffman as a superlative form of labeling, is used in this context ( 60 ). Nurses tend to label patients as bad when they do not express gratitude for the help they receive ( 61 , 62 ), yet patients who do not improve but try hard are regarded positively ( 46 ). Feelings of incompetency and powerlessness among professionals may lead to labeling patients as difficult, consequently leading to power struggles over control and autonomy ( 45 , 46 , 63 ).

A step beyond labeling is the exclusion of patients from mental health care. Creating barriers to specific forms of treatment or care legitimizes the denial of care. Critics have gone go so far as to state that mental health providers deny the very existence of severe and disabling diseases, such as schizophrenia, by constantly being too optimistic about patients' opportunities to conduct their lives outside psychiatric hospitals ( 64 ). As a result, responsibility for difficult patients is fended off, and patients may be passed on to another institution. Patients who do not fit into the system, because their problems differ from those of the mainstream, run a high risk of being labeled as difficult. This situation also occurs with patients who have alternative, nonmedical explanations or solutions for their health problems, such as maintaining a healthy lifestyle instead of using medication ( 20 ). Chronic patients run a high risk of encountering this problem, because their complex and long-term needs often do not fit into the psychiatric care system ( 11 , 12 , 13 ). According to this view, many difficult interactions are explained by the interpersonal stances of professionals and patients and by the mental health care system's tendency to consider atypical demands as difficult.

From an organizational perspective, the ongoing replacement of inpatient care by outpatient care is considered as possibly harmful for the difficult patient ( 65 ). When the psychiatric hospital ceases to be a safe haven that offers long-term stay and therapy, the pressures on both patient and professional in outpatient care increase. This situation may have negative consequences for the working alliance and the patient's health situation, especially when busy community mental health centers can devote little time to difficult, long-term therapies ( 65 ). Recent studies have stressed that the psychiatric hospital increasingly becomes a last resort for very specialized care or treatment of more disturbed difficult patients ( 48 , 66 ).

One study ( 67 ) showed that patients whose treatment borders on different health care terrains—specialized medical care or addiction treatment—run a greater risk of being considered difficult. Iatrogenic damage may be the result of the diffusion of responsibility among different health care professionals. Comparable matching problems are likely to occur when a patient shows or threatens criminal behavior. Subsequent exclusion from the mental health system may have a detrimental effect on the patient. In general, professionals appear to be reluctant to set limits and tend to diffuse responsibility with patients who violate or do not know the "rules of the game" in the mental health system ( 1 ).

Interventions

Many interventions suggested in the literature are rather standard and could therefore be characterized as common practice. Examples include respecting the patient, careful listening, validating feelings and behaviors, and being nonjudgmental ( 68 , 69 ). Yet difficult patients, as described in previous sections, seem to be very attentive to professionals' attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, these common practices are more important with this population than with patients who are not difficult. Apart from these standard interventions, some specific interventions are listed next, as well as interventions that consider the professional instead of the patient. Unfortunately, none of these interventions have been evaluated for effectiveness in empirical studies.

First, as stated earlier, a supportive and understanding attitude is suggested. A so-called holding environment, in which the patient may feel safe to experience different feelings and experiment with different behavior, is encouraged. To maintain the safety of this holding environment, setting limits for the patient is suggested. Other structuring interventions include assigning the patient the responsibility for his or her own safety, framing a clear treatment structure and contract, and maintaining one professional as a case manager for both patient and other professionals ( 1 , 23 , 70 ). Interpretation of transference and countertransference issues as they arise is necessary and effective and may serve to ameliorate the doctor-patient relationship ( 71 ). Others have recommended that modes of treatment or attitudes be modified according to different types of difficult patients, with different strategies for dealing with denying, dependent, and demanding patients ( 17 ). Also mentioned are the need for a nonauthoritative attitude and power sharing ( 45 ), forgiveness as a counterpart of a judgmental attitude ( 72 ), and consciousness of the patient's situation and situational factors ( 73 ).

Some more specific therapeutic techniques include slowly decreasing the amount of care ( 74 ), modifying dialectical behavior therapy ( 75 , 76 ), creating a very strict and clear treatment contract in behavioral terms ( 77 ), using strategic and paradoxical interventions ( 78 ), and establishing a specialized aftercare program for former inpatients considered to be difficult ( 79 ).

Additional interventions that professionals may use consist of two major categories: individual supervision and interdisciplinary team consultation. Through supervision, the attitude of the supervised professional may improve and treatment quality may increase. On the other hand, a parallel process may occur: the supervisor may consider the supervisee as a difficult person because none of the suggested interventions seem to work ( 18 , 43 , 80 ). Other options on a personal level include collaborating and consulting instead of working alone and maintaining balance in both private and personal life ( 49 ). Multidisciplinary meetings are suggested as a way to form a collective vision. In such meetings, staff feelings are channeled into more professional modes, and development of consistent treatment plans is endorsed ( 48 , 81 ). Sessions that value the views of different professions and lack the need of forming immediate solutions offer the best insight in team troubles and processes ( 6 ). Outside consultation by a third-party professional is a useful variant that may help immersed treatment teams to gain a fresh perspective ( 82 , 83 ). Last, reading literature on patient care is suggested to help students and trainees to gain perspective on the difficult patient's vantage point ( 84 , 85 ).

In summary, the professional should maintain a validating attitude and strict boundaries within a clear treatment structure. Consciousness of the patient's background and one's own limitations helps the professional to see different perspectives, and consultation and supervision may strongly reinforce the importance of different perspectives.

Discussion

As in daily practice, there is consensus in the literature about who difficult patients are and what they do. Yet why these patients are difficult and how they might best be treated are less clear according to the results of this review. We considered over 90 articles, but most of them contained few empirical findings. Quantitative empirical studies were limited to the characteristics of difficult patients, and qualitative studies mostly considered social processes, whereas the articles on explanations and interventions were theoretical in nature. Contributions from different mental health professions vary widely. Medical-psychiatric literature almost exclusively considered symptoms, behaviors, and diagnoses. Psychological literature largely focused on explanations of difficult behavior and the relationship between patient and professional. Nursing literature mainly considered the occurrence of difficult patients in a social context, the result of specific social processes such as labeling and exclusion. All considered treatment options, yet not in much detail.

The large variation in results is probably the consequence of the conceptual problem that underlies the term "difficult patient": being difficult is not an observable disease or symptom but a judgment made by mental health professionals. Moreover, the label seldom refers to a difficult treatment but almost always to a patient who is hard to be with ( 86 , 87 , 88 ).

The adjective "difficult" suggests the existence of a model patient who lives up to certain unwritten beliefs that seem to exist in and about mental health care. Some of these characteristics are covered in more detail by sociologists in writing about the sick role ( 46 , 89 , 90 ), yet here are some of the most important: the patient is not responsible for being ill; the patient makes a great effort to get better; the disease is clearly delineated, recognizable, and treatable; the disease, after treatment, is cured, and the patient leaves the system; the therapeutic encounter is pleasant and progressively effective; and the system is not responsible if the disease is not successfully treated.

Clearly, the typical patient in this review does not behave according to this sick role. The difficult patient we have discovered through the literature is either not motivated or ambivalently motivated for treatment and has a disease that does not neatly fit into one diagnostic category, which also does not gradually improve. The difficult patient is often unpleasant to be with, and although our patient may sometimes be out of sight, he or she almost always returns to start treatment all over again and sometimes blames the mental health system for taking too little or too much care before. In many of the articles reviewed, the question of whether the patient is deliberately behaving in a difficult manner is implicitly raised but seldom explicitly answered. This important question may have some major implications. If a patient is purposely difficult, does that mean that he or she is not ill? Should other standards be applied when the patient is not ill? Or is this particular behavior proof of a very serious disease that gravely affects the free will of the patient? And if this is so, should there be new definitions of certain diseases, and should new treatments be invented? Some authors seemed to favor this view, suggesting that over time effective treatments for difficult patients will emerge. These treatments will transform difficult patients into regular patients who are treated instead of judged ( 91 ). In a recent volume on difficult-to-treat patients, this optimism was endorsed by several treatment strategies ( 92 ), although critics have contended that this approach is too narrow ( 93 , 94 ).

This dichotomy between ill and not ill does not, however, seem helpful in either this review or daily practice. In order to differentiate among different patients, we suggest a gliding scale between a medical-psychiatric and a social-moral approach. The first approach largely excuses difficult behaviors because ill people cannot be held accountable for them. The second approach holds people accountable for their actions, independent of their health status. Though these two extremes are not very useful in everyday care, they may help to clarify the two attitudes that are often competing in the minds of professionals. Balancing these two approaches is necessary to prevent ineffective either-or discussions.

To illustrate this approach, a closer look at the three subgroups may help ( Table 1 ). The unwilling care avoiders (group 1) have the most objective psychiatric symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, and therefore will be considered ill ("mad"). They will be treated in mental health care with the use of methods that take the patients' vulnerable health status into account, such as assertive community treatment. The demanding care claimers (group 3), on the other hand, exert the most difficult behaviors and experience the least severe psychiatric symptoms and therefore are easily considered as nonpatients (or "bad" patients). Often, however, they are also treated, albeit within the justice system in which a social-moral attitude plays a larger role. An example of this kind of patient is one undergoing involuntary treatment that is focused on preventing recidivism to protect society. Both groups and settings have undergone major developments in recent years, resulting in clearer treatment approaches. Yet it is the group of ambivalent care seekers (group 2) that is the most challenging. Even more than the other groups, patients in this group show psychiatric symptoms, such as depression and suicidality, as well as difficult behaviors. Therefore, they are constantly subject to different judgments about their health status by professionals and thus are most at risk of facing either-or discussions.

Conclusions

Because of its conceptual nature, the difficult patient is not a new DSM category but is a result of professionals' implicit and explicit judgments about patients. When a professional calls a patient difficult, he or she says something about the degree to which a patient complies with the role of the ideal patient. The so-called difficult patient is always at risk of not being considered a real patient, in need of and deserving of care. Illness may be denied or exaggerated, both with detrimental results.

The second subgroup that has been described, the ambivalent care seekers, is especially at risk of poor treatment because a rigid approach to treatment (either medical-psychiatric or social-moral) may be harmful. With these patients, health care providers find it hard to maintain a clear strategy, as patients' behaviors evoke concern as well as annoyance. Concern refers to a caring attitude, whereas annoyance induces harsh judgments. Although these patients are ill, they do not benefit from a medical-psychiatric approach alone because they need more limits than are usually placed on psychiatric patients. On the other hand, the strict social-moral approach is also insufficient because it does not meet this group's need for care. Balancing the two approaches will help professionals work effectively with this type of difficult patient. Although some interventions for this subgroup have been highlighted in this review, they are merely free-standing actions that lack a unifying frame of reference. Unlike the other two groups, the group of ambivalent care seekers lacks overall treatment strategies and specific treatment settings. Apart from that, the effectiveness of the proposed interventions has not been researched. Future studies of difficult patients therefore should focus on describing, implementing, and evaluating interventions for the group of ambivalent care seekers. In these future studies, both the medical-psychiatric and social-moral approach should be favored within a clear conceptual framework.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by financial support from ZonMw ("Geestkracht" program) and Altrecht Mental Health Care (the Netherlands).

1. Neill JR: The difficult patient: identification and response. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 40:209-212, 1979Google Scholar

2. Colson DB, Allen JG, Coyne L, et al: Patterns of staff perception of difficult patients in a long-term psychiatric hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:168-172, 1985Google Scholar

3. Colson DB, Allen JG, Coyne L, et al: Profiles of difficult psychiatric hospital patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:720-724, 1986Google Scholar

4. Colson DB, Allen JG, Coyne L, et al: An anatomy of countertransference: staff reactions to difficult psychiatric hospital patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:923-928, 1986Google Scholar

5. Allen JG, Colson DB, Coyne L, et al: Problems to anticipate in treating difficult patients in a long-term psychiatric hospital. Psychiatry 49:350-358, 1986Google Scholar

6. Colson DB: Difficult patients in extended psychiatric hospitalization: a research perspective on the patient, staff and team. Psychiatry 53:369-382, 1990Google Scholar

7. Modestin J, Greub E, Brenner HD: Problem patients in a psychiatric inpatient setting: an explorative study. European Archives of Psychiatric and Neurological Sciences 235:309-314, 1986Google Scholar

8. Gallop R, Wynn F: The difficult inpatient: identification and response by staff. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 32:211-215, 1987Google Scholar

9. Robbins JM, Beck PR, Mueller DP, et al: Therapists' perceptions of difficult psychiatric patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 176:490-497, 1988Google Scholar

10. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry: Interactive Fit: A Guide to Non-Psychotic Chronic Patients. New York, Brunner Mazel, 1987Google Scholar

11. Bachrach LL, Talbott JA, Meyerson AT: The chronic psychiatric patient as a "difficult" patient: a conceptual analysis. New Directions for Mental Health Services 33:35-50, 1987Google Scholar

12. Bachrach LL: Planning services for chronically mentally ill patients. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 47:163-188, 1983Google Scholar

13. Menninger WW: Dealing with staff reactions to perceived lack of progress by chronic mental patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:805-808, 1984Google Scholar

14. Main T: The ailment, in The Ailment and Other Psychoanalytic Essays. Edited by Johns J. London, Free Association Books, 1989Google Scholar

15. Powers JS: Patient-physician communication and interaction: a unifying approach to the difficult patient. Southern Medical Journal 78:445-447, 1985Google Scholar

16. Groves JE: Taking care of the hateful patient. New England Journal of Medicine 298:883-887, 1978Google Scholar

17. Groves JE, Beresin EV: Difficult patients, difficult families. New Horizons: Science and Practice of Acute Medicine 64:331-343, 1998Google Scholar

18. Fiore RJ: Toward engaging the difficult patient. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 18:87-106Google Scholar

19. Strandberg G, Jansson L: Meaning of dependency on care as narrated by nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 17:84-91, 2003Google Scholar

20. Wright AL, Morgan WJ: On the creation of "problem" patients. Social Science and Medicine 30:951-959, 1990Google Scholar

21. Kirsch P: How they cling like shadows: object relations and the difficult patient. Psychotherapy Patient 3:43-54, 1986Google Scholar

22. Wong N: Perspectives on the difficult patient. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 47:99-106, 1983Google Scholar

23. Silver D: Psychotherapy of the characterologically difficult patient. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 28:513-521, 1983Google Scholar

24. Bongar B, Markey LA, Peterson LG: Views on the difficult and dreaded patient: a preliminary investigation. Medical Psychotherapy 4:9-16, 1991Google Scholar

25. Schwartz SR, Goldfinger SM: The new chronic patient: clinical characteristics of an emerging subgroup. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:470-474, 1981Google Scholar

26. Waska RT: Bargains, treaties, and delusions. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis 27:451-469, 1999Google Scholar

27. Waska RT: Working with difficult patients. Psychoanalytic Social Work 7:75-93, 2000Google Scholar

28. Shapiro D: The difficult patient or the difficult dyad? From a characterological view. Contemporary Psychoanalysis 28:519-524, 1992Google Scholar

29. Fonagy P: An attachment theory approach to treatment of the difficult patient. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 62:147-169, 1998Google Scholar

30. Chrzanowski G: Problem patients or troublemakers? Dynamic and therapeutic considerations. American Journal of Psychotherapy 34:26-38, 1980Google Scholar

31. Freedman N, Berzofsky M: Shape of the communicated transference in difficult and not-so-difficult patients: symbolized and desymbolized transference. Psychoanalytic Psychology 12:363-374, 1995Google Scholar

32. Burnham DL: The special-problem patient: victim or agent of splitting? Psychiatry 29:105-122, 1966Google Scholar

33. Maltsberger JT, Buie DH: Countertransference hate in the treatment of suicidal patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 30:625-633, 1974Google Scholar

34. Gallop R, Lancee W, Shugar G: Residents' and nurses' perceptions of difficult-to-treat short-stay patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:352-357, 1993Google Scholar

35. Podrasky DL, Sexton DL: Nurses' reactions to difficult patients. Image—The Journal of Nursing Scholarship 20:16-21, 1988Google Scholar

36. Santamaria N: The Difficult Patient Stress Scale: a new instrument to measure interpersonal stress in nursing. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 13:22-29, 1995Google Scholar

37. Santamaria N: The relationship between nurses' personality and stress levels reported when caring for interpersonally difficult patients. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 18:20-26, 2000Google Scholar

38. Arlow JA: Discussion of transference and countertransference with the difficult patient, in Between Analyst and Patient: New Dimensions in Countertransference and Transference. Edited by Meyers HC. Hillsdale, NJ, Analytic Press, 1986Google Scholar

39. Noonan M: Understanding the "difficult" patient from a dual person perspective. Clinical Social Work Journal 26:129-141, 1998Google Scholar

40. Bromberg PM: The difficult patient or the difficult dyad? Some basic issues. Contemporary Psychoanalysis 28:495-502, 1992Google Scholar

41. Fine R: Countertransference reactions to the difficult patient. Current Issues in Psychoanalytic Practice 1:7-22, 1984Google Scholar

42. Stolorow RD, Brandchaft B, Atwood GE: Intersubjectivity in psychoanalytic treatment: with special reference to archaic states. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 47:117-128, 1983Google Scholar

43. Laskowski C: The mental health clinical nurse specialist and the "difficult" patient: evolving meaning. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 22:5-22, 2001Google Scholar

44. Menninger RW: The therapeutic environment and team approach at the Menninger Hospital. Psychiatry and Clinical Neuro-sciences 52(suppl):S173-S176, 1998Google Scholar

45. Breeze JA, Repper J: Struggling for control: the care experiences of "difficult" patients in mental health services. Journal of Advanced Nursing 28:1301-1311, 1998Google Scholar

46. May D, Kelly MP: Chancers, pests and poor wee souls: problems of legitimation in psychiatric nursing. Sociology of Health and Illness 4:279-301, 1982Google Scholar

47. Lancee WJ, Gallop R: Factors contributing to nurses' difficulty in treating patients in short-stay psychiatric settings. Psychiatric Services 46:724-726, 1995Google Scholar

48. Munich RL, Allen JG: Psychiatric and sociotherapeutic perspectives on the difficult-to-treat patient. Psychiatry 66:346-357, 2003Google Scholar

49. Smith RJ, Steindler EM: The impact of difficult patients upon treaters: consequences and remedies. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 47:107-116, 1983Google Scholar

50. Najavits LM: Helping "difficult" patients. Psychotherapy Research 11:131-152, 2001Google Scholar

51. Lewis G, Appleby L: Personality disorder: the patients psychiatrists dislike. British Journal of Psychiatry 153:44-49, 1988Google Scholar

52. Gallop R, Lancee WJ, Garfinkel P: How nursing staff respond to the label "borderline personality disorder." Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:815-819, 1989Google Scholar

53. Yalom ID: The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 4th ed. New York, Basic Books, 1995Google Scholar

54. Gans JS, Alonso A: Difficult patients: their construction in group therapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 48:311-326, 1998Google Scholar

55. Leszcz M: Group psychotherapy of the characterologically difficult patient. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 39:311-335, 1989Google Scholar

56. Roth BE, Stone WN, Kibel HD: The Difficult Patient in Group: Group Psychotherapy With Borderline and Narcissistic Disorders. Madison, Conn: International Universities Press, 1990Google Scholar

57. Trexler JC: Reformulation of deviance and labelling theory for nursing. Image—The Journal of Nursing Scholarship 28:131-135, 1996Google Scholar

58. Carveth JA: Perceived patient deviance and avoidance by nurses. Nursing Research 44:173-178, 1995Google Scholar

59. Johnson M, Webb C: Rediscovering unpopular patients: the concept of social judgement. Journal of Advanced Nursing 21:466-475, 1995Google Scholar

60. Macdonald M: Seeing the cage: stigma and its potential to inform the concept of the difficult patient. Clinical Nurse Specialist 17:305-310, 2003Google Scholar

61. Kelly MP, May D: Good and bad patients: a review of the literature and a theoretical critique. Journal of Advanced Nursing 7:147-156, 1982Google Scholar

62. Jeffery R: Normal rubbish: deviant patients in casualty departments. Sociology of Health and Illness 1:90-107, 1979Google Scholar

63. Russel S, Daly J, Hughes E, et al: Nurses and difficult patients: negotiating non-compliance. Journal of Advanced Nursing 43:281-287, 2003Google Scholar

64. Coid JW: "Difficult to place" psychiatric patients. British Medical Journal 302:603-604, 1991Google Scholar

65. Holmes J: Psychiatry without walls: some psychotherapeutic reflections. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy 6:1-12, 1992Google Scholar

66. Fisher WH, Barreira PJ, Geller JL, et al: Long-stay patients in state psychiatric hospitals at the end of the 20th century. Psychiatric Services 52:1051-1056, 2001Google Scholar

67. Maltsberger JT: Diffusion of responsibility in the care of a difficult patient. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 25:415-421, 1995Google Scholar

68. Juliana CA, Orehowsky S, Smith-Regojo P, et al: Interventions used by staff nurses to manage "difficult" patients. Holistic Nursing Practice 11:1-26, 1997Google Scholar

69. Nield-Anderson L, Minarik PA, Dilworth JM, et al: Responding to 'difficult' patients. American Journal of Nursing 99:26-34, 1999Google Scholar

70. Berman AL (ed): Clinical issues: treating the difficult patient. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 20:267-274, 1990Google Scholar

71. Weiler MA: Interpretation of negative transference in non-analytic settings. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 17:223-236, 1987Google Scholar

72. Scheurich N: Moral attitudes and mental disorders. Hastings Center Report 32:14-21, 2002Google Scholar

73. Sledge WH, Fernstein AR: A clinimetric approach to the components of the patient-physician relationship. JAMA 278:2043-2048,1997Google Scholar

74. Frayn DH: Recent shifts in psychotherapeutic strategies with the characterologically difficult patient. Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa 11:77-81, 1986Google Scholar

75. Linehan MM: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford Press, 1993Google Scholar

76. Huffman JC, Stern TA, Harley RM, et al: The use of DBT skills in the treatment of difficult patients in the general hospital. Psychosomatics 44:421-429, 2003Google Scholar

77. Taylor CB, Pfenninger JL, Candelaria T: The use of treatment contracts to reduce Medicaid costs of a difficult patient. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 11:77-82, 1980Google Scholar

78. Johnson LD: Naturalistic techniques with the "difficult" patient, in Developing Ericksonian Therapy: State of the Art. Edited by Zeig JK, Lankton SR. Philadelphia, Brunner/Mazel, 1988Google Scholar

79. Wasylenki DA, Plummer E, Littmann S: An aftercare program for problem patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:493-496, 1981Google Scholar

80. Lauro L, Bass A, Goldsmith LA, et al: Psychoanalytic supervision of the difficult patient. Psychoanalytic Quarterly 72:403-438, 2003Google Scholar

81. Santy PA, Wehmeier PK: Using "problem patient" rounds to help emergency room staff manage difficult patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:494-496, 1984Google Scholar

82. Silver D, Book HE, Hamilton JE, et al: The characterologically difficult patient: a hospital treatment model. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 28:91-96, 1983Google Scholar

83. Silver D, Cardish RJ, Glassman EJ: Intensive treatment of characterologically difficult patients: a general hospital perspective. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 10:219-245, 1987Google Scholar

84. Shapiro J, Lie D: Using literature to help physician-learners understand and manage "difficult" patients. Academic Medicine 75:765-768, 2000Google Scholar

85. Batchelor J, Freeman MS: Spectrum: the clinician and the "difficult" patient. South Dakota Journal of Medicine 54:453-456, 2001Google Scholar

86. Staley JC: Physicians and the difficult patient. Social Work 36:74-79, 1991Google Scholar

87. Daberkow D: Preventing and managing difficult patient-physician relationships. Journal of Louisiana State Medical Society 152:328-332, 2000Google Scholar

88. Allen JG, Colson DB, Coyne L, et al: Difficult patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:672-673, 1987Google Scholar

89. Hartman D: Regarding the "difficult patient." British Journal of Psychiatry 175:192, 1999Google Scholar

90. Parsons T: The Social System. Glencoe, Scotland, Free Press, 1951Google Scholar

91. Kendell RE: The distinction between personality disorder and mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:110-115, 2002Google Scholar

92. Dewan MJ, Pies RW: The Difficult-to-Treat Psychiatric Patient. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001Google Scholar

93. Hinshelwood RD: The difficult patient: the role of "scientific psychiatry" in understanding patients with chronic schizophrenia or severe personality disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:187-190, 1999Google Scholar

94. Nathan, R: Scientific attitude to "difficult" patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 175:87-88, 1999Google Scholar