Use of the Sequential Intercept Model as an Approach to Decriminalization of People With Serious Mental Illness

Over the past several years, Summit County (greater Akron), Ohio has been working to address the problem of overrepresentation, or "criminalization," of people with mental illness in the local criminal justice system ( 1 , 2 ). As part of that effort, the Summit County Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services Board obtained technical assistance consultation from the National GAINS Center for People with Co-occurring Disorders in the Justice System. From that collaboration, a conceptual model based on public health principles has emerged to address the interface between the criminal justice and mental health systems. We believe that this model—Sequential Intercept Model—can help other localities systematically develop initiatives to reduce the criminalization of people with mental illness in their community.

The Sequential Intercept Model: ideals and description

We start with the ideal that people with mental disorders should not "penetrate" the criminal justice system at a greater frequency than people in the same community without mental disorders (personal communication, Steadman H, Feb 23, 2001). Although the nature of mental illness makes it likely that people with symptomatic illness will have contact with law enforcement and the courts, the presence of mental illness should not result in unnecessary arrest or incarceration. People with mental illness who commit crimes with criminal intent that are unrelated to symptomatic mental illness should be held accountable for their actions, as anyone else would be. However, people with mental illness should not be arrested or incarcerated simply because of their mental disorder or lack of access to appropriate treatment—nor should such people be detained in jails or prisons longer than others simply because of their illness.

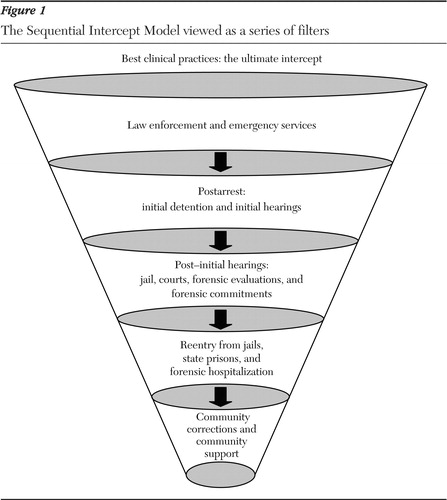

With both this ideal and current realities in mind, we envision a series of "points of interception" or opportunities for an intervention to prevent individuals with mental illness from entering or penetrating deeper into the criminal justice system. Ideally, most people will be intercepted at early points. Each point of interception can be considered a filter ( Figure 1 ). In communities with poorly developed mental health systems and no active collaboration between the mental health and criminal justice systems, the filters will be porous. Few will be intercepted early, and more people with mental illness will move through all levels of the criminal justice system. As systems and collaboration develop, the filter will become more finely meshed, and fewer individuals will move past each intercept point.

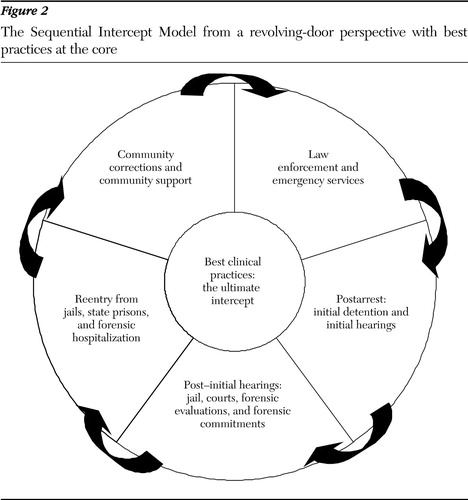

The Sequential Intercept Model complements the work of Landsberg and colleagues ( 3 ) who developed an action blueprint for addressing system change for people with mental illness who are involved in the New York City criminal justice system. The Sequential Intercept Model expands that work by addressing Steadman's ( 4 ) observation that people with mental illness often cycle repeatedly between the criminal justice system and community services. The model addresses his key question of how we can prevent such recycling by showing the ways in which people typically move through the criminal justice system and prompting considerations about how to intercept those with mental illness, who often have co-occurring substance use disorders.

Interception has several objectives ( 4 , 5 ): preventing initial involvement in the criminal justice system, decreasing admissions to jail, engaging individuals in treatment as soon as possible, minimizing time spent moving through the criminal justice system, linking individuals to community treatment upon release from incarceration, and decreasing the rate of return to the criminal justice system.

In contrast to the six critical intervention points identified in Landsberg's conceptual roadmap ( 3 ), we have specified the following five intercept points to more closely reflect the flow of individuals through the criminal justice system and the interactive nature of mental health and criminal justice systems ( Figure 2 ):

• Law enforcement and emergency services

• Initial detention and initial hearings

• Jail, courts, forensic evaluations, and forensic commitments

• Reentry from jails, state prisons, and forensic hospitalization

• Community corrections and community support services

In the next sections we describe the points of interception and illustrate them with examples of relevant interventions from the research and practice literature.

An accessible mental health system: the ultimate intercept

An accessible, comprehensive, effective mental health treatment system focused on the needs of individuals with serious and persistent mental disorders is undoubtedly the most effective means of preventing the criminalization of people with mental illness. The system should have an effective base of services that includes competent, supportive clinicians; community support services, such as case management; medications; vocational and other role supports; safe and affordable housing; and crisis services. These services must be available and easily accessible to people in need. Unfortunately, few communities in the United States have this level of services ( 6 ).

In addition to accessible and comprehensive services, it is increasingly clear that clinicians and treatment systems need to use treatment interventions for which there is evidence of efficacy and effectiveness ( 7 , 8 ). In many systems, evidence-based treatments are not delivered consistently ( 9 ). Examples of such interventions include access to and use of second-generation antipsychotic medications, including clozapine ( 10 ); family psychoeducation programs ( 11 ); assertive community treatment teams ( 12 ); and integrated substance abuse and mental health treatment ( 13 ). Integrated treatment is especially critical, given the fact that approximately three-quarters of incarcerated persons with serious mental illness have a comorbid substance use disorder ( 14 , 15 ).

Intercept 1: law enforcement and emergency services

Prearrest diversion programs are the first point of interception. Even in the best of mental health systems, some people with serious mental disorders will come to the attention of the police. Lamb and associates' ( 16 ) review of the police and mental health systems noted that since deinstitutionalization "law enforcement agencies have played an increasingly important role in the management of persons who are experiencing psychiatric crises." The police are often the first called to deal with persons with mental health emergencies. Law enforcement experts estimate that as many as 7 to 10 percent of patrol officer encounters involve persons with mental disorders ( 17 , 18 ). Accordingly, law enforcement is a crucial point of interception to divert people with mental illness from the criminal justice system.

Historically, mental health systems and law enforcement agencies have not worked closely together. There has been little joint planning, cross training, or planned collaboration in the field. Police officers have considerable discretion in resolving interactions with people who have mental disorders ( 19 ). Arrest is often the option of last resort, but when officers lack knowledge of alternatives and cannot gain access to them, they may see arrest as the only available disposition for people who clearly cannot be left on the street.

Lamb and colleagues ( 16 ) described several strategies used by police departments, with or without the participation of local mental health systems, to more effectively deal with persons with mental illness who are in crisis in the community: mobile crisis teams of mental health professionals, mental health workers employed by the police to provide on-site and telephone consultation to officers in the field, teaming of specially trained police officers with mental health workers from the public mental health system to address crises in the field, and creation of a team of police officers who have received specialized mental health training and who then respond to calls thought to involve people with mental disorders. The prototype of the specialized police officer approach is the Memphis Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) ( 20 , 21 ), which is based on collaboration between law enforcement, the local community mental health system, and other key stakeholders. A comparison of three police-based diversion models ( 22 ) found the Memphis CIT program to have the lowest arrest rate, high utilization by patrol officers, rapid response time, and frequent referrals to treatment.

Intercept 2: initial hearings and initial detention

Postarrest diversion programs are the next point of interception. Even when optimal mental health service systems and effective prearrest diversion programs are in place, some individuals with serious mental disorders will nevertheless be arrested. On the basis of the nature of the crime, such individuals may be appropriate for diversion to treatment, either as an alternative to prosecution or as an alternative to incarceration. In communities with poorly developed treatment systems that lack prearrest diversion programs, the prototypical candidate for postarrest diversion may have committed a nonviolent, low-level misdemeanor as a result of symptomatic mental illness.

If there is no prearrest or police-level diversion, people who commit less serious crimes will be candidates for postarrest diversion at intercept 2. In communities with strong intercept 1 programs, postarrest diversion candidates are likely to be charged with more serious acts. In such cases, although diversion at the initial hearing stage is an option and treatment in lieu of adjudication may be a viable alternative, some courts and prosecutors may look only at postconviction (intercept 3) interventions.

Postarrest diversion procedures may include having the court employ mental health workers to assess individuals after arrest in the jail or the courthouse and advise the court about the possible presence of mental illness and options for assessment and treatment, which could include diversion alternatives or treatment as a condition of probation. Alternatively, courts may develop collaborative relationships with the public mental health system, which would provide staff to conduct assessments and facilitate links to community services.

Examples of programs that intercept at the initial detention or initial hearing stage include the statewide diversion program found in Connecticut ( 23 ) and the local diversion programs found in Phoenix ( 24 ) and Miami ( 25 ). Although Connecticut detains initially at the local courthouse for initial hearings and the Phoenix and Miami systems detain initially at local jails, all three programs target diversion intervention at the point of the initial court hearing. A survey of pretrial release and deferred prosecution programs throughout the country identified only 12 jurisdictions out of 203 that attempt to offer the same opportunities for pretrial release and deferred prosecution for defendants with mental illness as any other defendant ( 26 ).

Intercept 3: jails and courts

Ideally, a majority of offenders with mental illness who meet criteria for diversion will have been filtered out of the criminal justice system in intercepts 1 and 2 and will avoid incarceration. In reality, however, it is clear that both local jails and state prisons house substantial numbers of individuals with mental illnesses. In addition, studies in local jurisdictions have found that jail inmates with severe mental illness are likely to spend significantly more time in jail than other inmates who have the same charges but who do not have severe mental illness ( 27 , 28 ). As a result, prompt access to high-quality treatment in local correctional settings is critical to stabilization and successful eventual transition to the community

An intercept 3 intervention that is currently receiving considerable attention is the establishment of a separate docket or court program specifically to address the needs of individuals with mental illness who come before the criminal court, so-called mental health courts ( 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ). These special-jurisdiction courts limit punishment and instead focus on problem-solving strategies and linkage to community treatment to avoid further involvement in the criminal justice system of the defendants who come before them. The National GAINS Center estimates that there are now 114 mental health courts for adults in the United States ( 33 ).

Intercept 4: reentry from jails, prisons, and hospitals

There is little continuity of care between corrections and community mental health systems for individuals with mental illness who leave correctional settings ( 34 ). Typically, communication between the two systems is limited, and the public mental health system may be unaware when clients are incarcerated. Mental health systems rarely systematically follow their clients once they have been incarcerated. In a recent survey of jails in New Jersey, only three jails reported providing release plans for a majority of their inmates with mental illness, and only two reported routinely providing transitional psychotropic medications upon release to the community ( 35 ).

Nationally, the issue of facilitating continuity of care and reentry from correctional settings is receiving increasing attention. In part these efforts are fueled by class action litigation against local corrections and mental health systems for failing to provide aftercare linkages, such as the successful Brad H case against the New York City jail system ( 36 ). In addition, pressure is increasing on corrections and mental health systems to stop the cycle of recidivism frequently associated with people with severe mental illness who become involved in the criminal justice system ( 37 , 38 , 39 ). The APIC model for transitional planning from local jails that has been proposed by Osher and colleagues ( 40 ) breaks new ground with its focus on assessing, planning, identifying, and coordinating transitional care. Massachusetts has implemented a forensic transitional program for offenders with mental illness who are reentering the community from correctional settings ( 41 ). The program provides "in-reach" into correctional settings three months before release and follows individuals for three months after release to provide assistance in making a successful transition back to the community.

Intercept 5: community corrections and community support services

Individuals under continuing supervision in the community by the criminal justice system—probation or parole—are another important large group to consider. At the end of 2003, an estimated 4.8 million adults were under federal, state, or local probation or parole jurisdiction ( 42 ). Compliance with mental health treatment is a frequent condition of probation or parole. Failure to attend treatment appointments often results in revocation of probation and return to incarceration. Promising recent research by Skeem and colleagues ( 43 ) has begun to closely examine how probation officers implement requirements to participate in mandated psychiatric treatment and what approaches appear to be most effective.

Other research by Solomon and associates ( 44 ) has examined probationers' involvement in various types of mental health services and their relationship to technical violations of probation and incarceration. Similar to mental health courts, a variety of jurisdictions use designated probation or parole officers who have specialized caseloads of probationers with mental illness. The probation and parole committee of the Ohio Supreme Court advisory committee on mentally ill in the courts ( 45 , 46 ) has developed a mental health training curriculum for parole and probation officers.

Discussion

Some people may argue that the basic building blocks of an effective mental health system are lacking in many communities, and therefore efforts to reduce the overrepresentation of people with mental illness in the criminal justice system are futile. This argument is not persuasive. Even the most underfunded mental health systems can work to improve services to individuals with the greatest need, including the group of people with serious and persistent mental disorders who have frequent interaction with the criminal justice system. Such efforts require close collaboration between the mental health and criminal justice systems.

The Sequential Intercept Model provides a framework for communities to consider as they address concerns about criminalization of people with mental illness in their jurisdiction. It can help communities understand the big picture of interactions between the criminal justice and mental health systems, identify where to intercept individuals with mental illness as they move through the criminal justice system, suggest which populations might be targeted at each point of interception, highlight the likely decision makers who can authorize movement from the criminal justice system, and identify who needs to be at the table to develop interventions at each point of interception. By addressing the problem at the level of each sequential intercept, a community can develop targeted strategies to enhance effectiveness that can evolve over time. Different communities can choose to begin at different intercept levels, although the model suggests more "bang for the buck" with interventions that are earlier in the sequence.

Five southeastern counties in Pennsylvania (Bucks, Chester, Delaware, Montgomery, and Philadelphia) used the Sequential Intercept Model as a tool to organize their work in a forensic task force charged with planning coordinated regional initiatives ( 47 ). As a result of that year-long effort, Bucks County staff organized a countywide effort to improve the local continuum of interactions and services of the mental health and criminal justice systems ( 48 ), and Philadelphia County started a forensic task force that uses the model as an organizing and planning framework. The model is also being used in a cross-training curriculum for community change to improve services for people with co-occurring disorders in the justice system ( 49 ).

Conclusions

Although many communities are interested in addressing the overrepresentation of people with mental illness in local courts and jails, the task can seem daunting and the various program options confusing. The Sequential Intercept Model provides a workable framework for collaboration between criminal justice and treatment systems to systematically address and reduce the criminalization of people with mental illness in their community.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of Henry J. Steadman, Ph.D., and the support of the National GAINS Center, the Summit County Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services Board, and the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health.

1. Munetz M, Grande TP, Chambers MR: The incarceration of individuals with severe mental disorders. Community Mental Health Journal 37:361-372, 2001Google Scholar

2. Summit County (Ohio) Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services Board: a systematic approach to decriminalization of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:1537-1538, 2003Google Scholar

3. Landsberg G: Planning for system care change for the mentally ill involved with the criminal justice system in New York City: a blueprint for action but obstacles to implementation. Community Mental Health Report, July/Aug 2004Google Scholar

4. Steadman HJ: Prioritizing and designing options for jail diversion in your community. Presented at the Technical Assistance and Policy Analysis tele-video conference, Delmar, NY, Oct 17, 2003Google Scholar

5. Promising Practices Committee: Pennsylvania's Southeast Region Inter-Agency Forensic Task Final Report: Subcommittee Report. Harrisburg, Pa, Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, July 12, 2002Google Scholar

6. New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Final Report. DHHS pub SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003Google Scholar

7. Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:179-182, 2001Google Scholar

8. Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:45-50, 2001Google Scholar

9. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, Co-investigators of the PORT Project: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patients Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11-20, 1998Google Scholar

10. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen, EB: Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications in reducing violent behavior among persons with schizophrenia in community-based treatment. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:3-20, 2004Google Scholar

11. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903-910, 2001Google Scholar

12. Phillips SD, Burns BJ, Edgar ER, et al: Moving assertive community treatment into standard practice. Psychiatric Services 52:771-779, 2001Google Scholar

13. Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, et al: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders: A Guide to Effective Practice. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

14. Abram KM, Teplin LA: Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees. American Psychologist 46:1036-1045, 1991Google Scholar

15. The Prevalence of Co-occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders in Jail. National GAINS Center Fact Sheet Series. Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center for People With Co-occurring Disorders in the Justice System, 2002Google Scholar

16. Lamb RL, Weinburger L, DeCuir WJ: The police and mental health. Psychiatric Services 53:1266-1271, 2002Google Scholar

17. Deane MW, Steadman HJ, Borum R, et al: Emerging partnerships between mental health and law enforcement. Psychiatric Services 50:90-101, 1999Google Scholar

18. Janik J: Dealing with mentally ill offenders. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin 61:22-26, 1992Google Scholar

19. Dupont R, Cochran S: Police response to mental health emergencies: barriers to change. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 28:338-344, 2000Google Scholar

20. Memphis Police Crisis Intervention Team. Memphis, Tenn, Memphis Police Department, 1999Google Scholar

21. Vickers B: Memphis, Tennessee, Police Department's Crisis Intervention Team: Bulletin from the Field: Practitioner Perspectives. NCJ 182501. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2000Google Scholar

22. Steadman HJ, Deane MW, Borum R, et al: Comparing outcomes of major models for police responses to mental health emergencies. American Journal of Public Health, 51:645-649, 2000Google Scholar

23. Frisman L, Sturges G, Baranoski M, et al: Connecticut's criminal justice diversion program: a comprehensive community mental health model. Community Mental Health Report 3:19-20, 25-26, 2001Google Scholar

24. Using Management Information Systems to Locate People With Serious Mental Illnesses and Co-occurring Substance Use Disorders in the Criminal Justice System for Diversion. National GAINS Center Fact Sheet Series. Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center for People With Co-occurring Disorders in the Justice System, 1999Google Scholar

25. Perez A, Leifman S, Estrada, A: Reversing the criminalization of mental illness. Crime and Delinquency 49:62-78, 2003Google Scholar

26. Clark J: Non-Specialty First Appearance Court Models for Diverting Persons With Mental Illness: Alternatives to Mental Health Courts. Delmar, NY, Technical Assistance and Policy Analysis Center for Jail Diversion, 2004Google Scholar

27. Axelson GL: Psychotic vs Non-Psychotic Misdemeanants in a Large County Jail: An Analysis of Pre-Trial Treatment by the Legal System. Doctoral dissertation. Fairfax, Va, George Mason University, Department of Psychology, 1987Google Scholar

28. McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC: Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 56:840-846, 2005Google Scholar

29. Goldkamp JS, Irons-Guynn C: Emerging judicial strategies for the mentally ill in the criminal caseload: mental health courts in Fort Lauderdale, Seattle, San Bernardino, and Anchorage. NCJ 182504. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2000Google Scholar

30. Griffin P, Steadman H, Petrila J: The use of criminal charges and sanctions in mental health courts. Psychiatric Services 53:1205-1289, 2002Google Scholar

31. Petrila J: The Effectiveness of the Broward Mental Health Court: An Evaluation. Policy Brief 16. Tampa, Fla, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Nov 2002. Available at www.fmhi.usf.edu/institute/pubs/newsletters/policybriefs/issue016.pdfGoogle Scholar

32. Steadman HJ, Davidson S, Brown C: Mental health courts: their promise and unanswered questions. Psychiatric Services 52:457-458, 2001Google Scholar

33. National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, TAPA Center for Jail Diversion, National GAINS Center for People With Co-occurring Disorders in the Justice System, et al: Survey of Mental Health Courts, Feb 2006. Available at www.mentalhealthcourtsurvey.com.Google Scholar

34. Griffin P: The Back Door of the Jail: Linking mentally ill offenders to community mental health services, in Jail Diversion for the Mentally Ill: Breaking Through the Barriers. Edited by Steadman HJ. Longmont, Colo, National Institute of Corrections, 1990Google Scholar

35. Wolff N, Plemmons D, Veysey B, et al: Release planning for inmates with mental illness compared with those who have other chronic illnesses. Psychiatric Services 53:1469-1471, 2002Google Scholar

36. Barr H: Transinstitutionalization in the courts: Brad H v City of New York, and the fight for discharge planning for people with psychiatric disabilities leaving Rikers Island. Crime and Delinquency 49:97-123, 2003Google Scholar

37. McKean L, Ransford C: Current Strategies for Reducing Recidivism. Chicago, Center for Impact Research, 2004. Available at www.impactresearch.org/documents/recidivismfullreport.pdfGoogle Scholar

38. New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, Subcommittee on Criminal Justice: Background Paper. DHHS pub no SMA-04-3880. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, June 2004Google Scholar

39. Re-Entry Policy Council: Charting the Safe and Successful Return of Prisoners to the Community. New York, Council of State Governments, 2005Google Scholar

40. Osher F, Steadman HJ, Barr H: A Best Practice Approach to Community Re-Entry From Jails for Inmates With Co-occurring Disorders: The APIC model. Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center, 2002Google Scholar

41. Hartwell S, Orr K: The Massachusetts forensic transition team program for mentally ill offenders re-entering the community. Psychiatric Services 40:1220-1222, 1999Google Scholar

42. Glaze LE, Palla S: Probation and parole in the United States, 2003. NCJ 205336. US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, 2004Google Scholar

43. Skeem J, Louden J: Toward evidence-based practice for probationers and parolees mandated to mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services 57:333-342, 2006Google Scholar

44. Solomon P, Draine J, Marcus SC: Predicting incarceration of clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Psychiatric Services 53:50-56, 2002Google Scholar

45. Hawk K: The Supreme Court of Ohio Advisory Committee on Mentally Ill in the Courts: A Catalyst for Change. Columbus, Supreme Court of Ohio, 2004. Available at www.sconet.state.oh.us/ACMIC/resources/catalyst.pdfGoogle Scholar

46. Stratton EL: Solutions for the Mentally Ill on the Criminal Justice System. Columbus, Supreme Court of Ohio, 2001. Available at www.sconet.state.oh.us/ACMIC/resources/solutions.pdfGoogle Scholar

47. Pennsylvania's Southeast Region Inter-Agency Forensic Task Force: Final Report. Harrisburg, Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services, July 12, 2002Google Scholar

48. Kelsey R: The Bucks County Forensic Mental Health Project: An Update. Presented at the GAINS Conference From Science to Services: Emerging Best Practices for People in Contact With the Justice System. Las Vegas, May 12-14, 2004Google Scholar

49. NIMH SBIR Adult Cross-Training Curriculum Project: Action Steps to Community Change: A Cross-Training for Criminal Justice/Mental Health/Substance Abuse System. Delmar, NY, Policy Research Associates, 2005Google Scholar