Experiences of and Attitudes Toward Mental Health Services Among Older Youths in Foster Care

Concerns about the quality of mental health services have led to increased solicitation of consumer feedback, especially among adult consumers ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ). The consumer revolution has had less of an impact among children and adolescents who are recipients of mental health care, especially youths in public custody whose participation in care may not be volitional ( 6 ).

Although some studies have been conducted ( 7 , 8 ), there remains a paucity of research on youths' perceptions of the services they receive ( 9 ). A few instruments have been developed to measure youths' satisfaction with care ( 8 , 10 , 11 , 12 ), yet parents are more commonly surveyed about their satisfaction with their child's services ( 13 , 14 ). Because stakeholders' priorities usually vary ( 15 ), parents' views may not accurately reflect youths' perspectives ( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ). For youths in foster care, caregivers may be even further removed from understanding the youth's treatment experience.

Although the technical aspects of treatment are often the focus of quality appraisals, the interpersonal dynamics between a practitioner and a consumer also merit attention ( 20 , 21 ). For mental health consumers in foster care, a positive relationship with a caring adult practitioner takes on added worth. Therapists have found that "growth-fostering relationships"—connections built on mutuality, authenticity, and empathy—have helped individuals overcome obstacles and achieve psychological well-being ( 22 , 23 ). Characteristics identified in youth-adult relationship dyads include authenticity, active listening, and mutual respect ( 24 ). Whether these relationship traits remain important for relationships between youth consumers and adult practitioners is less clear. A study of adults with serious mental illness uncovered priorities that were not previously identified, including feeling valued, receiving "extra things," and finding similarities in personal traits ( 25 ). Rapport between adult clients and their counselors has also been found to improve treatment retention and clinical outcomes ( 26 ).

In this study, youths in foster care were given an opportunity to voice their experiences with mental health services and specific providers. The purpose of this study was to identify and describe the characteristics that youths value in relationships with mental health professionals and the services they receive. Understanding youths' experiences and attitudes toward treatment may help to reduce underutilization or early termination of services in this age group ( 27 ). We hypothesized that youths' experiences may influence their attitudes toward care and subsequent service use.

Methods

Data for this project were collected as part of a larger, longitudinal study assessing the experiences of older youths making a transition from the foster care system ( 28 ). Study procedures were approved by the Washington University human subjects committee. Of the 450 youths in foster care who were eligible for the study, 406 youths from eight Missouri counties were interviewed in person near their 17th birthday about their experiences with mental health professionals and their attitudes toward mental health services. Six months later, 371 youths (91 percent of the original sample) completed phone interviews about specific providers and service use changes. At the first interview, 228 youths (56 percent) were female, and 228 (56 percent) were youths of color, primarily African American (N=206) ( 28 ). Further details about the sample have been published elsewhere ( 28 ). Data were collected between December 2001 and May 2003.

Of the original 406 youths, this study identified 389 as mental health consumers on the basis of self-reported experiences with mental health professionals and items from the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA) that measure lifetime mental health service use ( 29 ). With children older than ten years, the SACA has demonstrated good to excellent test-retest reliability for lifetime service use ( 30 ). At the time of the first interview, 38 percent of the 389 youths (N=149) reported currently receiving prescribed psychotropic medications ( 28 ). During the first interview, these youths were asked to describe "particularly positive" or "particularly negative" experiences with mental health professionals. Their attitudes toward services were measured by the confidence subscale of the Attitude Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help scale (ATSPPH) ( 31 ). The confidence subscale consists of nine items (for example, "A person with an emotional problem is not likely to solve it alone") scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0, strongly disagree, to 4, strongly agree. The confidence subscale has demonstrated acceptable reliability, with an alpha coefficient of .74 ( 31 ). In this study, an item assessing participants' attitudes toward medication was substituted for one of the original items. Responses were summed to create an attitude score that could range from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes toward services.

At the interview six months later, youths who were currently receiving outpatient therapy (N=89) were asked what they liked about their therapist, and youths in congregate care settings (N=113) were asked what they liked about their favorite direct care worker and their residential therapist or case manager. Answers were transcribed by the interviewers. Changes in medication and service use were also assessed.

Comments from youths were read repeatedly by two reviewers. Each reviewer flagged sections of texts or phrases that youths frequently mentioned. Consistent with the qualitative approach, no exact number of references was required to determine what constituted a theme. These themes—empirically observable regularities in the data—were labeled by each reviewer and then compared across reviewers. Similar themes had been identified by each reviewer and were jointly named. After developing coding schemes, two reviewers reread the transcripts and coded a randomly selected sample of 30 percent of the responses to establish interrater reliability. An overall kappa score of .75 was achieved (.71 to .79 for each individual question). Discrepancies were mutually reconciled between the two reviewers with input from the principal investigator. One reviewer coded the remaining responses. Each theme's appearance was tabulated to identify commonly mentioned themes.

Results

Positive experiences

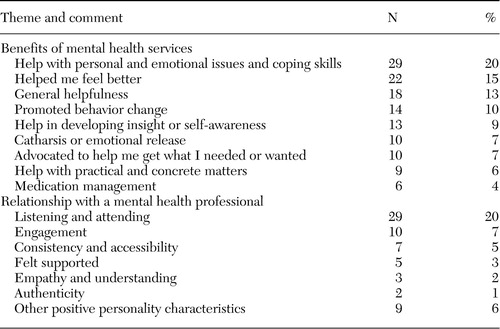

Of the 389 youths, 144 (37 percent) described a positive experience with a mental health professional. These experiences were classified into two broad categories: benefits of mental health services and relationship with a mental health professional. Each category is discussed below, with examples of youths' responses for prominent themes. Frequencies of categories mentioned by youths, which were based on the number of youths who reported a positive experience, are shown in Table 1 .

|

Benefits of mental health services. Youths named several benefits of mental health services, including receiving help with emotional issues and coping skills, experiencing positive behavior change, developing insight, and undergoing a catharsis. By choosing to articulate the benefits of care, youths may be indirectly challenging social pressures that question their participation.

Most commonly, youths mentioned receiving help with personal and emotional issues and developing coping skills. "Mr. A helped me cope with my father's and brother's deaths. Pushed me to cope even though I got mad." Other comments included "Helped me get my life on track—kept me in school, stopped me from some bad stuff," and "She helps me with my problems." As these comments show, youths in this sample encountered a variety of obstacles. Practical assistance in negotiating difficult emotional terrain was highly valued.

Youths also frequently reported changed feelings resulting from participation in mental health services. "They made me feel better about myself." "She eased my pain from my problems away." "Everything changed from dark to good." These youths vocalized an emotional outcome from a therapeutic encounter. A noticeable change demonstrates to youths that treatment is making a difference in their lives.

Some youths credited mental health professionals with promoting positive behavior changes—both simple and profound. Youths reported help with suicidal thoughts, drug use, grief, anger, and other problems. "One kept me from harming myself." "After the assault, I was not able to trust anyone. They have helped me with that." "I've changed my ways." For youths, observable changes in behavior further validate their participation in mental health care.

Relationship with a mental health professional. Youths articulated several desirable characteristics of mental health care providers. Major themes within this category included the provider's listening and attending skills, consistency, and support.

Strong communication skills were most frequently mentioned by youths. Beyond commenting on simply listening, youths also focused on the provider's ability to communicate acceptance and understanding. Examples of the comments include "[They] talk like they understand you, [and] make you feel like you can tell them anything." "Every experience with my therapist is positive. She listens and doesn't see [me] as something to diagnose." "[They are] good listeners, good to talk to."

Mental health professionals who are willing to engage youths beyond the office setting were valued by the youths we interviewed. "We would take walks and talk about problems." "My therapist took me to a conference to try to help me figure out what I want to do with my life." "Our staff takes us places."

Being available and consistent was important in therapeutic relationships. For these older youths who were "aging out" of the foster care system, establishing a relationship with a dependable adult was highly valued. "I could see him anytime I wanted." "She would always come talk to me, even if she didn't really have time." "I can count on him." These central themes suggest that youths appreciate when providers make time for them. Although youths realized that the practitioners were employed to work with them, youths perceived that providers also may take a genuine interest in them and their care.

Negative experiences

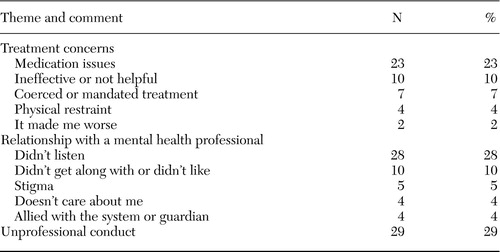

A negative experience was mentioned by 101 youths (26 percent). These experiences were classified into three categories: treatment concerns, relationship with a mental health provider, and unprofessional practice. Table 2 displays the frequencies for each category and the common themes.

|

Treatment concerns. When discussing negative experiences, several youths commented on the treatment they received. Medication management figured prominently among youths' negative experiences. One youth said, "They try to drug you up." Youths expressed frustration about receiving medication, especially when they were unsure that medication was indicated or effective. "They try to drill it in my head that I need medicine." "Psychiatrists think that they have a pill for everything." "Their doctors try to put you on meds that don't work."

Some youths complained of being overmedicated. "Doctors experiment different drugs on me." Side effects were also a concern. "Doctor put me on [medication]. It messed me up, messed my brain up." "They try to drug you up; you can't function."

Other youths felt that medication was sometimes prescribed prematurely. "Dr. B slapped meds on me the first day she met me. She didn't even take the chance to listen." "[They are] too quick to give meds instead of finding out what your problem is." These comments suggest that youths may experience the process of prescribing medication as coercive and disempowering.

When youths experienced little change as a result of their mental health care, they perceived services as ineffective. "They talk, but when I leave, everything is the same as before." "[My] therapist never talked about things that would help me and would not give me information to help me." "They don't seem to do much."

Although these youths clearly had expectations for change, they were disappointed at not having received the help they wanted or felt they needed, which led one youth to state, "My therapist just couldn't help me. She just couldn't."

Relationship with a mental health professional. The detrimental characteristics youths articulated were often the inverse of the previously mentioned sought-after traits.

Communication issues with a mental health professional were frequently cited by youths as problematic. Youths expressed feeling ignored and misunderstood. "We clashed, so therapy was no good." "They put words in your mouth." "[He] didn't hear what I said and told me that I would never change." A few youths mentioned material consequences as a result of communication difficulties. "I got into an argument with my counselor and was put back into foster care."

To improve understanding, one youth offered a practical suggestion.

"Sometimes psychologists don't get what you are trying to say. It would be good for psychologists to go back over what you are trying to say just to make sure."

Additional difficulties within the therapist-client relationship included feeling stigmatized or feeling that the provider was allied with the system or guardian.

Twenty-nine youths cited situations of unprofessional practice in which practitioners demonstrated a disregard of the professional or ethical standards of their position. These assertions varied from suspected dishonesty to demeaning acts. "One therapist told me I was a black male and that I needed to be more masculine and not gay." "I didn't like one counselor. She told the staff at the center something that was confidential and I got teased by other patients." "In order to get me to talk, my therapist would wrap me up in a blanket and my foster mom would sit on me. My therapist would make me sit on her lap like I was a little kid, and I was 13." These comments suggest that youths may encounter providers who stray from accepted practice standards and values.

Feedback for professionals

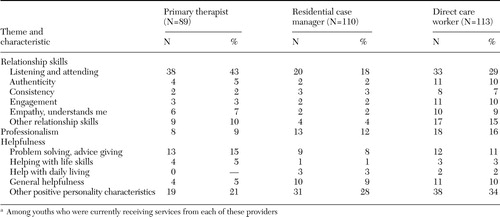

We also asked about preferences for specific professionals and characteristics attributed to the preferred professional. The results suggest that the youths appreciated similar characteristics of providers regardless of their role ( Table 3 ). Youths valued relationship skills, professionalism, and helpfulness across provider types. "She treats me like a person, not a foster kid" (describing a residential case manager). "Doesn't try to use psychology to get at you. Talks like a regular person" (primary therapist). "He knows what he is talking about" (primary therapist). "She got my meds situated. She comes up with good solutions for problems" (primary therapist). "He is helpful when it comes to man-to-man problems" (direct care worker).

|

a Among youths who were currently receiving services from each of these providers

Attitudes toward service use. The association between the types of experiences youths reported and their overall score on the ATSPPH was assessed by using SAS 9.1 for analysis of variance. The results suggested significant attitude differences (F=13.77, df=3, 384, p<.001). Post hoc Duncan testing revealed that youths who had only negative experiences had significantly less positive attitudes than youths who had only positive experiences, youths who had both types of experiences, and youths who made no comments.

Changes in service use. We hypothesized that service use may be related to youths' experiences of or attitudes toward services. Seventy youths who were receiving services from a mental health professional or counselor at baseline had discontinued services six months later. No association was found between service use changes and the experiences youths reported or their attitudes toward services. Youths who had negative service experiences were not more likely to terminate services.

Changes in medication regimens were also assessed. Although 23 youths made negative comments about medication at baseline, only one of these youths reported receiving different medications during the next six months.

Discussion

As has been found in similar studies ( 7 , 8 , 21 ), youths' reports of experiences with mental health services focused on interpersonal aspects of their relationships with providers and the perceived benefits of their care. Medication management, a theme not found in previous studies, featured notably in this sample's comments. Characteristics unique to this population ( 28 ) as well as increases in medication use since the previous studies ( 32 ) may explain this emphasis.

A few youths mentioned positive experiences with medication; however, almost one-fourth of youths who reported negative experiences mentioned medication concerns. Negative attitudes toward medication are difficult to understand without additional information about the context of the youth's care (such as symptom severity, medication type, or duration of treatment). Youths' attitudes toward pharmaceutical interventions mirrored those of adult mental health service users ( 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ).

Although previous research on relationship building accentuates authenticity and mutuality ( 22 , 23 , 24 ), these themes were less salient in this sample. These youths may have been hesitant to form close relationships with providers because of personal abuse histories ( 37 ). They may benefit from interventions that focus on building growth-fostering relationships with adults. Concerns about providers' ethical behavior underscore the importance of adult oversight and involvement in the care of youths. For foster care youths, caseworkers should continually appraise the quality of mental health care received by youths.

Within a system of care, youths interact with a number of mental health professionals. Our findings suggest that youths appreciate common attributes among providers, including good communication skills and helpfulness. Because youths in congregate care settings were asked to provide feedback on their "favorite" direct care worker, youths may have selected staff who were more professional or clinical in their interactions, resulting in fewer differences among providers.

Youths' open-ended comments about service experiences corresponded with their attitudes toward services. However, youths' experiences were unrelated to changes in services or medications. This unexpected finding may be explained by the fact that the youths in this study were in public custody. Because many such youths are mandated to receive treatment, decisions about service use are not determined solely by the youths.

This study had some limitations. The sample was restricted to 17- to 18-year-old youths in foster care from only a few counties in one state. These youths may not be representative of all youths in foster care or of adolescent consumers who are not in public custody. Older youths in foster care may be more likely to have a longer duration and greater frequency of mental health service use. Additionally, embedding open-ended questions in a long survey does not engender in-depth responses. Purely qualitative interviews might uncover more about the personal meaning of salient themes expressed by youths.

Conclusions

In an era in which evidence-based practice often reflects technical components of care, these findings highlight the importance of therapeutic relationships in the mental health service experience. Practitioners working with youths should be encouraged not to overlook the importance of basic relationship-building skills in engaging youths in treatment.

The youths in our study seemed to be calling for better communication with providers and more personalized attention. Many seemed to feel unheard by providers, especially in the area of medication. Youths' dissatisfaction with medication did not seem to translate into changes in their prescriptions.

Altering service delivery by encouraging youths to express concerns and involving youths in decision making may improve their attitudes toward services. Unfortunately, system constraints, such as brief appointment times imposed by public insurance reimbursement structures, may create sizable barriers to providing care that is satisfactory to vulnerable populations. Despite these impediments, high-quality care is no less important to individuals in these populations. Because understanding the preferences of young consumers is an important step in providing high-quality care, future work should continue to seek youths' voices.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by grant R01-MH-61404 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

1. Clark CC, Scott EA, Boydell KM et al: Effects of client interviewers on client-reported satisfaction with mental health services. Psychiatric Services 50:961-963, 1999Google Scholar

2. Friedrich RM, Hollingsworth B, Hradek E, et al: Family and client perspectives on alternative residential settings for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:509-514, 1999Google Scholar

3. Granello DH, Granello PF, Lee F: Measuring treatment outcomes and client satisfaction in a partial hospitalization program. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:50-63, 1999Google Scholar

4. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Thiele J. Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 49:929-934, 1998Google Scholar

5. Baker L, Zucker PJ, Gross MJ: Using client satisfaction surveys to evaluate and improve services in locked and unlocked adult inpatient facilities. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:51-64, 1998Google Scholar

6. Garland AF, Aarons GA, Saltzman MD, et al: Correlates of adolescents' satisfaction with mental health services. Mental Health Services Research 2:127-139, 2000Google Scholar

7. Garland AE, Besinger BA: Adolescents' perceptions of outpatient mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies 5:355-375, 1996Google Scholar

8. Shapiro JP, Welker CJ, Jacobsen BJ: The Youth Client Satisfaction Questionnaire: development, construct validation and factor structure. Journal of Child Clinical Psychology 26:87-98, 1997Google Scholar

9. Jensen PS, Hoagwood K, Petti T: Outcomes of mental health care for children and adolescents: II. literature review and application of a comprehensive model. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1064-1077, 1996Google Scholar

10. Brannan AM, Sonnichsen SE, Heflinger CA: Measuring satisfaction with children's mental health services: validity and reliability of the satisfaction scales. Evaluation and Program Planning 19:131-141, 1996Google Scholar

11. Garland AF, Saltzman MD, Aarons GA: Adolescent satisfaction with mental health services: development of a multidimensional scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 23:165-175, 2000Google Scholar

12. Stuntzner-Gibson D, Koren PE, DeChillo N: The Youth Satisfaction Questionnaire: what kids think of services. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services 76:616-624, 1995Google Scholar

13. Magura S, Moses BS: Clients as evaluators in child protective services. Child Welfare 63:99-111, 1984Google Scholar

14. Martin JS, Petr CG, Kapp SA: Consumer satisfaction with children's mental health services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 20:211-226, 2003Google Scholar

15. Fischer EP, Shumway M, Owen RR: Priorities of consumers, providers, and family members in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 53:724-729, 2002Google Scholar

16. Copeland VC, Koeske G, Greeno C: Child and mother client satisfaction questionnaire scores regarding mental health services: race, age, and gender correlates. Research on Social Work Practice 14:434-442, 2004Google Scholar

17. Godley SH, Fiedler EM, Funk RR: Consumer satisfaction of parents and their children with child/adolescent mental health services. Evaluation and Program Planning 21:31-45, 1998Google Scholar

18. Lambert WM, Salzer S, Bickman L: Clinical outcome, consumer satisfaction, and ad hoc ratings of improvement in children's mental health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:270-279, 1998Google Scholar

19. Garland AF, Lewczyk-Boxmeyer CM, Gabayan EN et al: Multiple stakeholder agreement on desired outcomes for adolescents' mental health services. Psychiatric Services 55:671-676, 2004Google Scholar

20. Donabedian A: The Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring, vol 1. Ann Arbor, Mich, Health Administration Press, 1980Google Scholar

21. Pickett SA, Lyons JS, Polonus T, et al: Factors predicting patients' satisfaction with managed mental health care. Psychiatric Services 46:722-723, 1995Google Scholar

22. Miller JB: Toward a New Psychology of Women. Boston, Beacon Press, 1986Google Scholar

23. Miller JB, Stiver IP: The healing connection: how women form relationships in therapy and in life. Boston, Beacon Press, 1997Google Scholar

24. Spencer R, Jordan JV, Sazama J: Growth-promoting relationships between youth and adults: a focus group study. Families in Society 85:354-362, 2004Google Scholar

25. Ware N, Tugenberg T, Dickey B: Practitioner relationships and quality of care for low-income persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:555-559, 2004Google Scholar

26. Joe GW, Simpson DD, Dansereau DF, et al: Relationship between counseling rapport and drug abuse treatment outcomes. Psychiatric Services 52:1223-1229, 2001Google Scholar

27. Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Kiser L, et al: Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatric Services 52:1179-1189, 2003Google Scholar

28. McMillen JC, Scott LD, Zima BT, et al: Use of mental health services among older youths in foster care. Psychiatric Services 55:811-817, 2004Google Scholar

29. Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K et al: The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): adult and child reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:1032-1039, 2000Google Scholar

30. Horwitz, SM, Hoagwood K, Stiffman AR, et al: Reliability of the Services Assessment for Children and Adolescents. Psychiatric Services 52:1088-1094, 2001Google Scholar

31. Fischer EH, Turner JL: Orientations to seeking professional help: development and research utility of an attitude scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 35:79-90, 1970Google Scholar

32. Warner LA, Pottick KJ, Mukherjee A: Use of psychotropic medications by youths with psychiatric diagnoses in the US mental health system. Psychiatric Services 55:309-311, 2004Google Scholar

33. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:196-201, 1998Google Scholar

34. Carrick R, Mitchell A, Powell RA, et al: The quest for well-being: a qualitative study of the experience of taking antipsychotic medication. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice 77:19-33, 2004Google Scholar

35. Loffler W, Kilian R, Toumi M, et al: Schizophrenic patients' subjective reasons for compliance and noncompliance with neuroleptic treatment. Pharmopsychiatry 36:105-112, 2003Google Scholar

36. Happell B, Manias E, Roper C: Wanting to be heard: mental health consumers' experiences of information about medication. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 13:242-248, 2004Google Scholar

37. Sparks E: Relational experiences of delinquent girls: a case study, in How Connections Heal: True Stories From Relational-Cultural Therapy. Edited by Walker M, Rosen WB, Miller JB. New York, Guilford, 2004Google Scholar