Patterns and Prevalence of Arrest in a Statewide Cohort of Mental Health Care Consumers

Minimizing criminal justice involvement among persons with severe mental illness has become a major focus of policy makers and officials from both the mental health and criminal justice systems. From the collaboration of these systems various interventions have evolved over the past ten to 15 years to help divert arrestees with mental illness to an appropriate array of mental health services ( 1 ). These mechanisms, which target primarily low-level offenders, have been introduced at several points within the criminal justice process—from the street to the courthouse. Such interventions include specialized training for police officers ( 2 , 3 ), pre- and postbooking jail diversion programs ( 4 , 5 ), mental health courts ( 6 , 7 ), and reentry programs for individuals with serious mental illness who have been released from correctional settings ( 8 ). Support for these programs has been forthcoming from local, state, and federal agencies and was the focus of the Mentally Ill Offender Treatment and Crime Reduction Act of 2004 (S.1194), which passed both houses of Congress and was signed into law by President George W. Bush.

Empirical evidence marshaled to contextualize these interventions comes from various sources and settings. Among the most frequently cited are data on the considerable prevalence of mental illness in correctional settings. These prevalence estimates have been obtained in various ways, including field epidemiologic studies ( 9 , 10 ), surveys of correctional administrators ( 11 ), and reports of mental health service use by correctional inmates ( 12 , 13 ). A second perspective on criminal justice involvement among persons with mental illness is found in an accumulating body of reports on arrest histories of persons served in various community-based settings, such as the recent overview of the criminal histories of persons served in California's community mental health centers ( 14 ).

These data have been useful for planning mental health services and treatment protocols in the respective settings. But information on persons confined in correctional settings or served in particular mental health service entities provides an incomplete picture of the scope and nature of criminal justice involvement among persons with severe mental illness. Discourse on this issue has been further narrowed by the fact that, with a few exceptions, such as New York's Nathaniel Project, which serves felons with serious mental illness ( 15 ), virtually all diversion programs, mental health courts, and reentry programs serve those involved with misdemeanor-level crimes. Indeed, motivated by a need to address the so-called criminalization problem by connecting or in some cases reconnecting such offenders with mental health services, planners of services operating at the interface of the mental health and criminal justice systems often have little knowledge of the other, sometimes more worrisome offending patterns exhibited by persons who have severe mental illness ( 16 ).

Gaining a broadened perspective on criminal justice involvement among persons with mental illness clearly is critical to developing interventions and services for the full spectrum of individuals in this population. But such a perspective needs to be informed by a broader, more population-based picture of the offending patterns displayed by persons with severe mental illness than is available. A first step in developing such a knowledge base is to examine arrest patterns exhibited by members of a broad but well-defined population over a specified period.

The aim of this study was to provide such information. Specifically, we examined arrest patterns in a statewide cohort of individuals who received public mental health services in a given year and whose arrest records were examined over a nearly ten-year follow-up period. We describe the percentage of cohort members arrested for various offenses over the period as well as their patterns of rearrest and also touch briefly on the sociodemographic correlates of arrest. In doing so, we draw on a longitudinal tradition that has guided criminologists, such as Wolfgang and colleagues ( 17 ) in their landmark study Delinquency in a Birth Cohort and Sampson and Laub ( 18 ) in Crime in the Making . The approach has been successfully used in research on offenders with mental illness. Harry and Steadman ( 19 ) examined offending in a cohort of Missouri mental health center clients, and Steadman and colleagues ( 20 , 21 , 22 ) examined criminal justice involvement among cohorts of persons discharged from a New York state hospital in 1968 and 1975. However, comparable data on contemporary arrest patterns have not been generally available to planners and policy makers concerned with this population.

Methods

Sample

The statewide cohort examined here consisted of all individuals 18 years or older who received inpatient, case management, or residential services from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (DMH) during Massachusetts fiscal year 1992 (July 1, 1991, through June 30, 1992). These inclusion criteria allowed us to capture most individuals meeting DMH's eligibility criteria for adult services in that year. Criteria included a diagnosis of a major adult axis I psychiatric disorder, such as schizophrenia or major affective disorder; significant functional impairment; and an intensive pattern of mental health service use. (DMH also provided services to some individuals with axis II diagnoses, in particular borderline personality, who met the other inclusion criteria.) Studies of DMH service recipients from this period provide additional background on this cohort. Roughly 60 percent of individuals entering a DMH hospital for treatment of mental illness in the early 1990s met criteria for substance abuse ( 23 ). In addition, approximately 40 percent of cohort members were Medicaid beneficiaries in 1992 and were receiving other forms of public assistance ( 24 ).

Data sources

The cohort was identified by merging and then eliminating duplicate DMH case management, inpatient, and residential program-use files by using an internally developed identifier. Data on criminal offending were obtained from the Massachusetts Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI). CORI records are the official criminal history records used by the Massachusetts Trial Court and include all arraignments (and therefore all arrests), dates, charges, and other information pertaining to the processing and disposition of arrests occurring in Massachusetts in the 24 hours before the request for information. We included in our analyses all arrests occurring between January 1991 and late December 2000, thus providing just under ten full years of observation.

Study approval and analyses

This study was approved by a medical school institutional review board and by the DMH Central Office Research Review Committee. The project was also reviewed and approved by the Massachusetts Criminal History Systems Board, which oversees access to CORI data.

Analyses of arrest patterns were based on the number of arraignment dates (which correspond to arrest) appearing in each individual's CORI record. Arrests and charges were examined differently because an individual can be arrested and arraigned once on several different charges—for example, assault and battery and drug possession. In examining charges, we assigned individuals to all offense categories for which they had ever been charged. Thus persons having one arrest could be included in several offense categories, depending on the charges filed against them, whereas a person arrested multiple times on the same charge would be included in that charge category only once.

The ten-year prevalence of arrest (the percentage of cohort members arrested) was calculated for all offenses. In a second set of analyses we examined temporal dimensions of arrest. We used the number of total arraignment dates per individual and the number of arraignment dates in multiple years as a measure of persistence in offending over the observation period. Finally, we compared prevalence rates across categories of gender, race, and age.

Results

Cohort characteristics

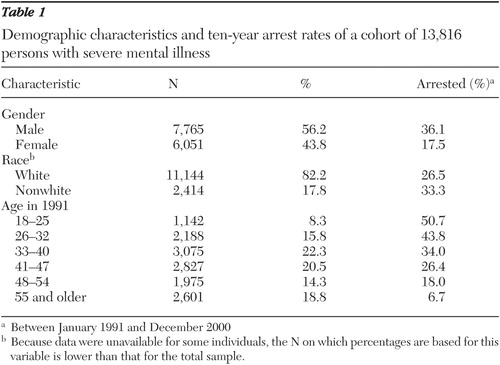

A total of 13,816 individuals met criteria for inclusion in our cohort. Their demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1 . These data describe a population that is largely white and disproportionately male. There is a roughly normal distribution of persons among age groupings, with the largest proportions in the categories 33 to 40 years and 41 to 47 years. Diagnostic categories are not included in these descriptive data because diagnostic data were inconsistent over time, thus precluding examinations of the effects of diagnosis on offending patterns. Clearly this is an important variable; however, the relatively narrow DMH diagnostic eligibility criteria assure us that our cohort included only individuals with serious mental illness. Data on race were unavailable for some individuals, as indicated by the sample for that variable (13,558) shown in Table 1 , which is lower than that for the total sample (13,616). In addition, the available race and ethnicity categories (white or nonwhite) are unfortunately extremely limited with respect to their utility in examining the effects of ethnicity on offending.

|

Criminal offense categories

Preliminary inspection of these data revealed dozens of different charges for which cohort members had been arrested over the observation period. Meaningful discussion of these offenses required that they be reduced to a workable number of categories. Existing offense taxonomies, in particular those used in the FBI's Uniform Crime Report, were considered but proved inadequate for our purposes because of the heavy emphasis on felonies and lack of specificity regarding misdemeanors. A categorization process was therefore undertaken by an interdisciplinary group, which included, among other specialties, a former criminal defense attorney and an individual with graduate training in criminal justice. This process yielded ten specific categories, which are shown in the box on the next page, along with the offenses they comprise. For two categories, crimes against persons and crimes against property, an effort was made to distinguish between serious offenses (such as felonies) and less serious misdemeanors. Assault and battery on a police officer was included as a separate category because of its significance for law enforcement personnel.

Summary and classification of charges lodged against cohort members

Serious violent crimes

Murder; nonnegligent manslaughter; forcible rape; robbery (including armed robbery); aggravated assault and battery with a dangerous weapon, against a person over age 65, against a disabled person, or to collect a debt

Less serious crimes against persons

Domestic violence (not resulting in a charge of serious violent crime), simple assault, simple assault and battery, threatening behavior or intimidation, indecent sexual assault (not rising to the legal definition of forcible rape), and violation of a restraining order

Assault and battery on a police officer

Serious property offenses

Burglary, larceny of an item worth more than $500, welfare fraud, receiving stolen property, uttering (passing bad checks), breaking and entering, arson, and motor vehicle theft

Less serious property crimes

Theft or shoplifting of an item worth less than $500; malicious destruction of property

Motor vehicle offenses

Operating a vehicle without a license or without compulsory insurance or so as to endanger, attaching license plates illegally, leaving the scene of an accident, or driving while intoxicated

Crimes against public order

Being a disorderly person, disturbing the peace, setting a false alarm, instigating a bomb hoax, trespassing, and consuming alcohol in a public place in violation of open-container law

Crimes against public decency

Offenses related to sex for hire (soliciting prostitution or being a common street walker), indecent exposure, and lewd and lascivious behavior

Drug-related offenses

Possession of a controlled substance, possession with intent to distribute and distribution or manufacture of or trafficking in a controlled substance, and conspiracy to violate the Controlled Substance Act

Firearm violations

Carrying a dangerous weapon, illegally discharging a firearm, and possessing a firearm without a license or permit

Miscellaneous

Misdemeanors with low rates of occurrence not easily classified in any of the above categories

Prevalence of arrest

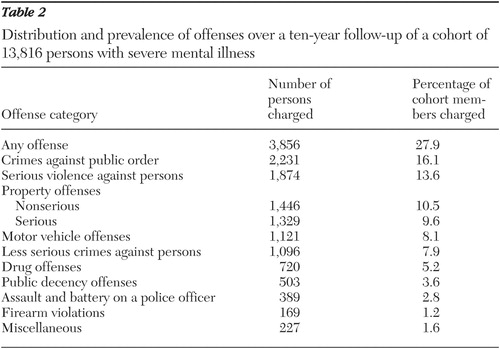

Data on total offenses and the number and percentage of cohort members charged with offenses in each category are shown in Table 2 , arranged in descending order of frequency. In all, 3,856 cohort members (27.9 percent) were arrested at least once over the roughly ten-year period. About 16 percent of the cohort was arrested for a crime against public order, but other, more serious offenses were only slightly less common; 13.6 percent of cohort members were arrested at least once for one of the serious crimes against persons.

|

Patterns of rearrest

The modal number of arrests was two and the maximum 71. Analysis of arrests across multiple years indicated that persons arrested in a given year had roughly a 40 percent chance of rearrest in the next year, a likelihood that attenuated in subsequent years. A small number of persons experienced arrests across much of the observation period; 13 persons experienced arraignments in each year.

A pattern often observed by criminologists suggests that a small proportion of offenders accounts for a large percentage of arrests ( 25 ). In our study 5 percent of arrestees accounted for roughly 17 percent of the arrests. Less than 1.5 percent of the cohort accounted for just under 20 percent of all arrests.

Distribution of offending across demographic groups

The reported 27.9 percent prevalence rate applied to the entire cohort but varied across demographic subgroups. As shown in Table 1 , the percentage of men arrested was more than double that for women (36.1 percent for men, 17.5 percent for women; continuity-corrected χ2 = 585.23, df=1, p<.001) and higher among individuals classified as nonwhite as opposed to white (26.5 percent for white, 33.3 percent for nonwhite; continuity-corrected χ2 =46.50, df=1, p<.001). Variation was also noted across age groups; as shown in Table 1 , just over half of cohort members between 18 and 25 in 1991 had at least one arrest during the period. The percentage arrested declined gradually across successively older age groupings.

Discussion

The approach used in this study enabled us to identify arrest patterns for a statewide, well-defined cohort observed over a fixed period. We point to several caveats for interpreting these findings. The population we examined consisted of individuals whose psychiatric illnesses were sufficiently serious and disabling that they had been deemed eligible for services under the relatively stringent eligibility criteria typical of state mental health agencies in the early 1990s. As we indicated, this cohort included many individuals who were poor and who also met criteria for substance abuse. As such, it was likely representative of the populations served by such agencies in many states during that period. However, because these findings were based on observations of state mental health agency service recipients, they may not be generalizable to persons served in other types of systems or to individuals not receiving services from any provider.

We should note that our estimates are based on the assumption that all cohort members were at risk for the full observation period, an assumption that is probably incorrect. This group likely experienced spells of incapacitation, that is, periods when patients were hospitalized, incarcerated, or otherwise prevented from engaging in certain types of criminal activities. We have not adjusted for this risk, nor have we adjusted for mortality. The impact of this nonadjustment is unclear. We can assume that persons found guilty of serious crimes would likely experience some type of institutional commitment. This incapacitation would not affect the observed percentage of individuals with at least one arrest but might affect recidivism patterns. (We note that one potentially incapacitating intervention—hospitalization—does not always prevent offending. Cases of inpatients charged with assault, arson, theft, and other offenses have been reported, and there is growing sentiment that patients committing such offenses should be prosecuted [ 26 ].)

In viewing these arrest data, one also should be mindful of potential period effects. The observation period for this study spanned the 1990s, an era marked by significant upheavals in public mental health systems, including the advent of managed care and intensified efforts to close state hospitals ( 27 , 28 ). Although previous analyses observed minimal criminal justice impact associated with the introduction of managed care in Massachusetts ( 29 ), the cumulative effects of these interventions may have altered the risk of criminal contact for some individuals. It was also during this period that the development of jail diversion, specialized police units, reentry programs, and other such services began. It is unclear whether such nascent diversion mechanisms or even simply the emerging policy perspective that drove their development affected the risk of arrest in this group.

Finally, arrest is a measure of criminal justice involvement and not necessarily of criminality. The arrests observed here reflect the perceptions and responses of police to observed deviant behavior, not the outcome of the full criminal justice process.

With these factors in mind, we discuss our findings' implications for policy makers and for future research. A potentially important direction for future analysis concerns the interaction of known criminological risk factors and severe mental illness. The observed arrest patterns indicate considerable criminal justice contact in this population but also reveal substantial variation across individuals and demographic subgroups. The direction of these effects—elevated risk of arrest for persons who are male, young, and not white—is consistent with that typically observed in the general population ( 30 ).

However, the strength of these effects appears, at least for one variable—gender—to be considerably weaker among members of this cohort than in the general offender population. In our sample, the percentage of men arrested was slightly more than double that of women. However, analysis of data from the Uniform Crime Report showed a larger male-to-female arrest ratio of roughly 3.8 to 1 ( 31 ). For several reasons, these two data sources cannot be directly compared, and in any case further explanation of what appears to be an interaction effect between gender and mental illness is beyond the scope of this article. Nonetheless, this trend warrants further investigation, as do other potential interactions of mental illness with age and race.

Draine and colleagues ( 32 ) have observed that many persons with serious mental illness offend not because they are mentally ill but because they are poor and share with other similarly situated persons exposure to various criminogenic risk factors. Our data reflect this perspective in the prevalence of property and motor vehicle arrests—the kind of offenses likely committed by economically disadvantaged persons who need or desire goods they cannot afford. Examining these socioenvironmental issues in a large cohort such as this one could be useful in determining how these risk factors are expressed and lead to the design of mental health services that might moderate such risk.

These data have further implications for the development of diversion mechanisms. As we noted, much attention has been focused on persons arrested for so-called nuisance crimes, offenses we categorized as crimes against public order. Indeed, the use of arrest in managing these behaviors has been a major focus of the "criminalization" discussion and of efforts to develop programs to divert such arrestees from the criminal justice system to the mental health system ( 16 ). Whether many of the "nuisance" charges reported here resulted from efforts by police to resolve situations in which mental health interventions were unavailable or deemed ineffective cannot be discerned from our data. These charges were the most common among this group, however, and, as such, these data lend support for ongoing efforts to develop better linkages between mental health and criminal justice agencies for managing such low-level offenders.

But although nuisance crimes comprised the modal offense category, other, more serious offenses were nearly as prevalent. Two categories, serious violent crimes and serious property crimes, are of particular concern because they include felonies that constitute serious threats to public safety. Persons charged with felonies have typically been ineligible for standard diversion programs. Data from the Nathaniel Project, which was mentioned above, have shown considerable success in preventing reoffending in this group ( 15 ). These programs have yet to become widely adopted, however, and many arrestees with mental illness facing felony charges who are found guilty will become the clientele of correctional mental health services and later, perhaps, of reentry programs.

Much of the discussion surrounding the criminalization of mental illness has focused on the failure of treatment systems to engage and retain persons who, as a result, become involved with the criminal justice system ( 33 ). It is important to point out that the entire cohort we observed was, at least when identified, receiving critical services such as case management and residential placement. This raises the question of whether and to what extent the arrests reported here are attributable to individuals' disengagement from those services or whether those services failed to prevent criminal activity among some recipients. Further research will examine in greater detail the relationship between receipt of services and likelihood of arrest and describe how socioenvironmental factors might mediate such effects.

Finally, as we have noted, the frequently arrested constitute a small subgroup of individuals and less than 2 percent of our cohort. These persons obviously present major clinical and economic challenges to both the mental health and criminal justice systems. Data on their behavior patterns and risk factors need to be obtained and incorporated into the planning of efforts to reduce their criminal justice involvement.

Conclusions

These data represent the first products of a program of research designed to identify risk factors for offending among persons with serious mental illness and to provide mental health service systems with an empirical base for planning programmatic interventions that can both reduce risk of arrest and better assist those who are arrested. An important first step, to which we hope these data contribute, is identifying the scope and patterns of criminal justice involvement and the prevalence of various offenses in this population.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant MH-65615 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

1. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Gross BH: Community treatment of severely mentally ill offenders under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system: a review. Psychiatric Services 50:907-913, 1999Google Scholar

2. Borum R: Improving high-risk encounters between people with mental illness and the police. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 28:332-337, 2000Google Scholar

3. Steadman HJ, Stainbrook KA, Griffin P, et al: A specialized crisis response site as a core element of police-based diversion programs. Psychiatric Services 52:219-222, 2001Google Scholar

4. Steadman HJ, Deane MW, Morrissey JP, et al: A SAMHSA research initiative assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 50:1620-1623, 1999Google Scholar

5. Steadman HJ, Naples M: Assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for persons with mental illness and co-occurring substance abuse disorders. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 23:163-170, 2005Google Scholar

6. Steadman HJ, Davidson S, Brown C: Mental health courts: their promise and unanswered questions. Psychiatric Services 52:457-458, 2001Google Scholar

7. Wolff N: Courting the court: courts as agents for treatment and justice, in Research in Community and Mental Health, vol 12. Edited by Fisher WH. Boston, Elsevier, 2003Google Scholar

8. Hartwell SW, Orr K: The Massachusetts forensic transition program for mentally ill offenders re-entering the community. Psychiatric Services 50:1220-1222, 1999Google Scholar

9. Teplin LA: The prevalence of severe mental disorder among male urban jail detainees: comparison with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. American Journal of Public Health 80:663-669, 1990Google Scholar

10. Teplin LA Abram KM, McClelland GM: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women jail detainees. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:505-512, 1996Google Scholar

11. Ditton P: Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, US Dept of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999.Google Scholar

12. Wolff N, Maschi T, Bjerklie JR: Profiling mentally disordered offenders: a case study of New Jersey prison inmates. Journal of Correctional Health Care, in pressGoogle Scholar

13. Blitz C, Wolff N, Pan K, et al: Mental illness in prison and its impact on community residence post-release: implications for recovery and community integration. American Journal of Public Health, in pressGoogle Scholar

14. Theriot MT, Segal S: Involvement with the criminal justice system among new clients at outpatient mental health agencies. Psychiatric Services 56:179-185, 2005Google Scholar

15. The Nathaniel Project: An Alternative to Incarceration Program for People With Serious Mental Illness Who Have Committed Felony Offenses. Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center, 2002Google Scholar

16. Fisher WH, Silver E, Wolff N: Beyond criminalization: toward a criminologically informed mental health policy and services research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 33:544-557, 2006Google Scholar

17. Wolfgang M, Figlio R, Sellin T: Delinquency in a Birth Cohort. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1972Google Scholar

18. Sampson RJ, Laub JH: Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points Through Life. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1993Google Scholar

19. Harry B, Steadman HJ: Arrest rates of patients treated at a community mental health center. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:862-866, 1988Google Scholar

20. Steadman HJ: Critically reassessing the accuracy of public perceptions of the dangerousness of the mentally ill. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22:310-316, 1981Google Scholar

21. Ribner SA, Steadman HJ: Recidivism among offenders and ex-mental patients. Criminology 21:411-442, 1981Google Scholar

22. Steadman HJ, Cocozza JJ, Melick ME: Explaining the increased arrest rate among mental patients: the changing clientele of state hospitals. American Journal of Psychiatry 135:816-820, 1978Google Scholar

23. Peterson L, O'Regan M, Fisher WH, et al: Patterns and prevalence of substance abuse among state hospital patients. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, Atlanta Ga, Oct 12, 1991Google Scholar

24. Fisher WH, Normand SL, Dickey B, et al: Managed mental health care's effects on arrest and forensic commitment. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 27:65-77, 2004Google Scholar

25. Shannon L: Criminal Career Continuity: Its Social Context. New York, Human Sciences Press, 1988Google Scholar

26. Appelbaum K, Appelbaum PS: Prosecution as a response to violence by psychiatric patients, in Patient Violence and the Clinician. Edited by Eichelman BS, Hartwig AC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

27. Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, et al: Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Affairs 14(3):173-184, 1995Google Scholar

28. Dickey B, Normand SLN, Norton E, et al: Managing the care of schizophrenia: lessons from a four-year Massachusetts Medicaid study. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:945-952, 1996Google Scholar

29. Upshur CC, Benson PR, Clemens E, et al: Closing state mental hospitals in Massachusetts: policy, process and impact. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 20:195-215, 1997Google Scholar

30. Steffensmeier D, Allan E: Looking for patterns: gender, age and crime, in Criminology: A Contemporary Handbook. Edited by Sheley J. Belmont, Calif, Wadsworth, 1988Google Scholar

31. Federal Bureau of Investigation: Crime in the United States 2000: Uniform Crime Reports. Washington DC, US Department of Justice, 2005Google Scholar

32. Draine J, Salzer M, Culhane D, et al: Poverty, social problems, and serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:899, 2002Google Scholar

33. Wolff N, Diamond RJ, Helminiak TW: A new look at an old issue: people with mental illness and the law enforcement system. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:152-165, 1997Google Scholar