Impact of Consumer-Operated Services on Empowerment and Recovery of People With Psychiatric Disabilities

Consumer-operated services are programs largely developed by people with psychiatric disabilities for people with psychiatric disabilities ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). Peer support is a prototype service of this kind. Essential to these programs are actions that foster the "helper principle." Namely, people feel better about themselves not only when they receive support and resources from peers but also when they are able to give and be of assistance to others. This kind of help can boost the self-esteem of participants, which in turn can suppress self-stigma that might worsen a person's experiences of mental illness ( 4 , 5 ). People who believe they are personally empowered about most facets of their life are less likely to experience the self-stigma of mental illness ( 4 ).

Empowerment is a complex phenomenon. It has been defined as personal control over decisions about all domains of life—not just mental health care but also vocation, residence, and relationships ( 6 , 7 ). Rogers and colleagues ( 8 ) more fully developed the processes related to personal control in a survey of 271 people with serious mental illness. Five factors emerged from this work that have been validated on subsequent research samples ( 9 ). These are self-esteem and self-efficacy, power and powerlessness, community activism and autonomy, optimism about and control over the future, and righteous anger. We would expect that participation in peer support would enhance all elements of empowerment.

Related to empowerment is the idea of recovery. Recovery has been defined as living a satisfying life while continually addressing the impact of one's mental illness ( 10 , 11 , 12 ). It has been compared with the experiences of persons with physical disabilities who are able to overcome deficits that result from physical illness and trauma and accomplish most life goals when provided suitable assistance and reasonable accommodations. Like empowerment, recovery is a multifaceted phenomenon; a complete definition comprises several factors. Research on the Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) ( 9 , 13 ) has uncovered five factors: personal confidence and hope, willingness to ask for help, being goal and success oriented, reliance on others, and not being dominated by symptoms. RAS subfactors have been validated against measures of psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, hope, and empowerment. Like empowerment, we would expect the RAS factor to be positively associated with participation in peer support programs.

Despite ample discussion about peer support, empowerment, and recovery, few studies have examined correlates to participation in consumer-operated services. Recent articles on consumer-operated services emphasize description, process assessment, and case studies rather than examination of impact and outcomes ( 3 ). For example, one study examined five consumer-run mental health services and included descriptor variables such as consumer satisfaction, the nature of services, and the day-to-day interactions of consumers in these programs ( 14 , 15 ). These kinds of descriptive studies did not find a link between actual participation in peer support programs and commensurate experiences related to empowerment and recovery. This article takes a first step in this direction by examining how empowerment and recovery vary across groups who have and have not recently participated in peer support.

Methods

Data from this study were obtained between January 2000 and October 2001 during a baseline assessment of participants in the consumer-operated services project. This multisite study, funded by community mental health services, examined the impact of consumer-run services on people with psychiatric disabilities. Criteria for the definition of consumers included a DSM-IV axis I diagnosis consistent with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression, and a significant functional disability that resulted from the mental illness. People with primary diagnoses of substance abuse and V codes were excluded. Proxies that represented significant functional disability included receipt of Social Security Disability Insurance, two or more stays in a state hospital, or self-reported interference with housing, employment, or social support.

Research participants were administered several interview-based measures before entering the consumer-operated services project. As part of the baseline assessment, participants were asked questions about program activity. One item was relevant to the goals of this study. Participants responded yes or no to the question, "Have you received peer or mutual support in the past four months?" We limited our analyses to baseline data because after the baseline was completed, half the sample was randomly assigned to peer support and half was randomly assigned to no peer support. The baseline provided an assessment of uninfluenced rates of peer support in a large sample of people with serious mental illness. Another question of interest in these analyses was whether peer support represents a general effect that is evident across various kinds of support or is an experience specific to consumers of mental health services. To examine this question, participation in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) was also assessed. A general effect would show that positive correlations for participation in peer support diminish to nonsignificant levels when AA is added to the equation.

Two additional measures were collected at baseline and assessed recovery and empowerment. Participants completed the RAS ( 9 ), a 41-item scale on which respondents described themselves by using a 5-point agreement scale (5, strongly agree). Sample items include "I have a desire to succeed" and "I can handle it if I get sick again." Results of a confirmatory factor analysis mirrored the five recovery factors discussed above in the introduction to this report ( 13 ). Additional analyses supported the reliability and validity of the factors.

Research participants also completed the Empowerment Scale ( 8 ) The scale comprises 28 statements about personal empowerment, which respondents answer on a 4-point agreement scale (4, strongly disagree). Items were reverse-scored where appropriate so that a high total score on the Empowerment Scale represented high endorsement of that factor. Results of an exploratory factor analysis yielded the five empowerment factors reviewed above in the introduction. Additional analyses showed the Empowerment Scale to have satisfactory reliability and validity ( 9 ).

Results

A total of 1,824 individuals completed baseline analyses and provided usable data. Missing values for some items included in this analysis may have lowered the number of specific analyses to 1,750. The sample included 1,094 women (60 percent) and had a mean±SD age of 41.8±10.4 years (range 18-78). A total of 599 participants (33 percent) had not received a high school diploma, 460 participants (25 percent) had graduated from high school or received a GED, 508 (28 percent) had had some college or vocational training, 102 (6 percent) had received an associate's degree, 95 (5 percent) had obtained a bachelor's degree, and 55 (3 percent) had had some graduate school. In terms of ethnicity, 433 participants (24 percent) described themselves as African American, 1,356 (74 percent) as European American, 62 (3 percent) as Latino or Hispanic, 329 (18 percent) as Native American, and 25 (1 percent) as Asian or Pacific Islander. Note that the cumulative frequency of ethnic affiliations is greater than 100 percent because some participants identified themselves with more than one ethnic group. In terms of the sample's marital status, 850 (47 percent) were single or never married, 229 (13 percent) were married, 652 (36 percent) were separated or divorced, and 76 (4 percent) were widowed.

In terms of peer support in the previous four months, 819 participants (45 percent) said they had received such support. To compare specific and general effects, we asked research participants to report participation in AA; 564 (31 percent) indicated that they had attended at least one AA meeting during the four months that preceded the baseline.

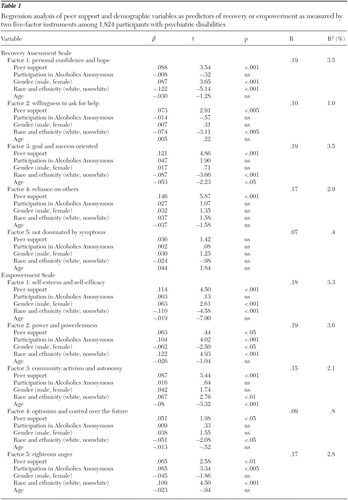

Multiple regression analysis was completed with the five factors from either the RAS or from the Empowerment Scale as dependent variables. Summaries of indices from these equations are provided in Table 1 . Independent variables included demographic variables—gender, age, and race and ethnicity (white or nonwhite)—to simulate effects that may influence the equations. Participation in peer support and AA was coded as a binary variable (1=yes and 0=no).

|

Demographic variables were significantly associated with the first three RAS factors. An interesting finding across these RAS factors was the significant positive association between nonwhite ethnicity and recovery. Support from AA was related only to factor 3, being goal and success oriented, but the association did not reach significance (p=.06). Peer support was found to be significantly associated with four of the five RAS factors: personal confidence and hope, willingness to ask for help, being goal and success oriented, and reliance on others. None of the independent variables was associated with factor 5, not dominated by symptoms.

As in the previous set of regressions, demographic variables were significantly associated with several of the five Empowerment Scale factors. Ethnicity was found to be associated with all of the Empowerment Scale factors, although interpretation of these correlations is a bit more complex. Similar to findings from the RAS, for the Empowerment Scale nonwhites were more likely than whites to report a greater sense of empowerment in two of the five empowerment factors: factor 1, self-esteem and self-efficacy, and factor 4, optimism and control over the future. Ethnicity was inversely related to the remaining three factors. Participation in AA was significantly associated with two of the five factors. Those with AA experiences in the previous four months reported a greater sense of power and more righteous anger. Peer support among consumers was associated with all five factors. Individuals with more peer support during the four-month window reported greater empowerment.

One finding in this study of particular concern is addressed more fully in the Discussion section. Namely, the R 2 value was quite low for each of the ten equations, ranging from .4 to 3.5 percent. This result suggests that the independent variables in the ten equations accounted for very little variance in the dependent variable.

Discussion

Despite the professional literature's reflecting a large interest in consumer-operated services, empirical data indicating the effect of these services on people with psychiatric disabilities need to develop. The goal of our cross-sectional analyses was to test assertions about consumer-operated services, recovery, and empowerment. Namely, we would expect to find a significant association among these variables. This expectation was supported in our study. Consumer-operated services in the form of peer support in this study were found to be positively associated with nine of the ten indices of recovery and empowerment. This association remained significant despite demographic variables that were also significantly (p<.05) correlated with recovery or empowerment factors. Even more compelling, associations between recovery or empowerment and peer support remained significant in cases where participation in AA also led to significant correlations.

Given that this was a cross-sectional study, the results cannot help in determining whether consumer-operated services caused better recovery and empowerment. However, these findings seem to support hypotheses of this kind. Completion of the multisite study from which the baseline data were collected will help us address the causality issues. Also missing from the analyses was an assessment of how recovery and empowerment changed the more the person participated in consumer-operated services.

Equations generated by these regression analyses yielded small R 2 values, indicating that findings from the study accounted for a miniscule percentage of the variance in RAS and Empowerment Scale factors. This finding may be a limitation of the kinds of analyses done in this overpowered design. Nevertheless, the findings remain interesting for two reasons. First, peer support was found to be associated with nine of the ten recovery and empowerment factors assessed in this article. Second, in instances where AA participation also accounted for a significant association, the peer support variable was significantly correlated with the recovery or empowerment factor sharing the specificity of effects. Third, low correlations of recovery and empowerment with peer support are similar to the effect size of results in the earlier construct validity of the RAS ( 12 ). Despite these assets, the findings remain puzzling. The low effect size may have resulted from the binary variable used to represent participation in peer support. Perhaps a continuous variable representing peer support would yield higher shared variance. Additional analyses are needed to determine the precision of findings from the RAS. Similar research will continue to enhance our knowledge about consumer-operated services.

1. Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, et al: Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 6:165-187, 1999Google Scholar

2. Mowbray CT, Robinson, EA, Holter MC: Consumer drop-in centers: operations, services, and consumer involvement. Health and Social Work 27:248-262, 2002Google Scholar

3. Solomon P, Draine J: The state of knowledge on the effectiveness of consumer provided services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25:20-28, 2001Google Scholar

4. Corrigan PW, Watson AC: Paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 9:35-53, 2002Google Scholar

5. Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Larson JE, et al: The influences and the effects of the self-stigma of mental illness. Social Work Research, in pressGoogle Scholar

6. Rapport J: Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology 15:121-148, 1987Google Scholar

7. Segal SP, Silverman C, Tempkin T: On empowerment and self help. Community Mental Health Journal 31:215-227, 1995Google Scholar

8. Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, et al: Consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services 48:1042-1047, 1997Google Scholar

9. Corrigan PW, Giffort D, Rashid F, et al: Recovery as a psychological construct. Community Mental Health Journal 35:231-240, 1999Google Scholar

10. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:11-23, 1993Google Scholar

11. Deegan PE: Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:91-97, 1996Google Scholar

12. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A: Recovery from schizophrenia: a criterion-based definition. In Recovery in Mental Illness: Broadening Our Understanding of Wellness. Edited by Ralph RO, Corrigan PW. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2004Google Scholar

13. Corrigan PW, Salzer M, Ralph RO, et al: Examining the factor structure of the Recovery Assessment Scale. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:1035-1042, 2004Google Scholar

14. Mowbray CT, Chamberlain P, Jennings M, et al: Consumer-run mental health services: results from five demonstration projects. Community Mental Health Journal 24:151-156, 1988Google Scholar

15. Mowbray CT, Wellwood R, Chamberlain P: Project Stay: a consumer-run support service. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 12:33-42, 1988Google Scholar