Mortality Among Discharged Psychiatric Patients in Florence, Italy

Studies on mortality among psychiatric patients show a higher risk than in the general population. These estimates range from a slight increase to a risk that is five times higher ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ). A recent meta-analysis that included 152 studies from 1966 to 1995 estimated the overall risk of death as twice as high as that of the general population ( 6 ). This meta-analysis indicated that all types of mental disorders involve an increased mortality risk; patients with organic mental disorders and patients who abuse drugs have the highest relative risk, especially for natural deaths, whereas unnatural deaths are particularly high for individuals with schizophrenia and those with affective disorders.

Some studies have shown a higher relative risk of mortality, particularly from unnatural causes, during the first two years after hospital discharge ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ). Evidence for excess mortality has been demonstrated in all types of settings, among hospitalized patients, including long-stay patients ( 12 , 13 , 14 ) and those acutely hospitalized either before or after discharge ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 15 , 16 ), as well as among those in outpatient treatment ( 2 , 17 , 18 , 19 ) and in community populations ( 20 , 21 ).

Since 1978, the year that the Italian Psychiatric Reform Law (Public Law 180) closing down mental hospitals was implemented, most psychiatric services have been community based. This law integrated new and old psychiatric services within the National Health System and established psychiatric units within general hospitals (with up to 15 beds for each unit). It also set stringent limitations on compulsory admissions. Therefore, hospitalization in psychiatric units is mostly reserved for patients experiencing an acute illness—both first episodes and relapses—and for compulsory admissions. Currently, the psychiatric bed ratio is about .1 bed per 1,000 residents in Italy overall and .06 per 1,000 in Tuscany ( 22 , 23 ). The ratio in Italy is the lowest in Europe, where ratios range from .5 per 1,000 in Spain to 3.5 per 1,000 in the Netherlands ( 24 ).

In Italy most studies of mortality have involved samples of long-stay patients ( 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ). A few studies, known as the Case Register studies, have been conducted with outpatients in community-based services ( 31 , 32 ). Only one study has determined mortality risk among patients admitted to a psychiatric unit of a single general hospital from 1978 to 1994 ( 33 ).

Our study was conducted in Florence, an area where the reform law was properly implemented. Comprehensive care is delivered by program staff who make intensive home visits and provide day care either in the home or in a local facility. Psychosocial programs and clinical case management have been established that seek to avoid hospitalization as much as possible ( 34 ). We included in our study all psychiatric patients admitted in 1987 to the eight psychiatric units in the province of Florence.

This study sought to determine the overall and cause-specific mortality of a cohort of psychiatric inpatients admitted in 1987 and followed up 16 years after discharge in 2002 and compared it with mortality expected in the general population. Another objective was to evaluate the association of excess mortality from natural or unnatural causes with clinical and sociodemographic variables and time elapsed from first hospital admission.

Methods

The cohort included all patients admitted in 1987 to the eight psychiatric care units of the province of Florence, which had a population of about 880,000 in the 1991 census. Both first admissions and relapses were included. Only residents of the province were considered. Clinical and sociodemographic data were collected for each patient from clinical records. Life status as of December 31, 2002, and causes of death were obtained via record linkage to the Regional Mortality Registry, which collects all death certificates of people residing in Tuscany ( 35 ).

Clinical and sociodemographic information at the time of hospitalization was recorded as follows: age (stratified by decades), marital status (unmarried, married, widowed, and separated or divorced), employment status (employed or unemployed), and hospitalization (first admission or relapse). Diagnosis at discharge was documented according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) and categorized into five groups: schizophrenia disorders, including schizophrenic psychoses ( ICD-9 code 295), paranoid states (297), and other nonorganic psychoses (298); affective psychoses (296); neurotic and personality disorders, including neurotic disorders (300), personality disorders (301), adjustment reaction disorders (309), and depressive disorders, not elsewhere classified (311); organic psychoses, including senile and presenile organic psychotic conditions (290), transient organic psychotic conditions (293), other organic psychotic conditions (chronic) (294), mild mental retardation (317), and other specified mental retardation (318); and substance use disorders (291, 292, and 303-305).

Overall and cause-specific mortality was considered. All deaths resulting from suicide ( ICD-9 E950-E959) or other violent causes (E800-E929, E960-E999) were considered unnatural deaths. Causes of death that could be related indirectly to behavior, such as alcoholic cirrhosis and AIDS, were categorized as natural.

To compare the mortality risk of the psychiatric patient cohort with that of the general population, standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) were calculated. SMRs were estimated as ratios between the observed and the expected number of deaths. The expected deaths were calculated by multiplying the cause-specific mortality rate for the whole region of Tuscany for various groups (that is, for age, sex, and period of death) by the corresponding number of person-years. SMRs for the analysis involving time since discharge were calculated only for patients whose 1987 hospitalization was a first admission. Chi square tests for linear trends were performed.

A Poisson multivariate regression of the observed-to-expected ratio on age, sex, marital status, occupation, discharge diagnosis, and hospitalization (admission or relapse) was then conducted. Separate regression models were fitted for natural and unnatural deaths. External standard rates were incorporated into the multiplicative model, with the logarithm of the expected number of natural or unnatural deaths as the offset variable ( 36 ). These analyses were performed by using STATA 8.2 ( 37 ).

The data in this observational study remained anonymous and were analyzed in the aggregate. Therefore institutional review board approval was not necessary in Italy.

Results

The initial cohort in 1987 included 930 patients older than 15 years. Sixty-five individuals were excluded because they were not residents of the province of Florence at the date of admission. Another 20 were excluded because some sociodemographic data were not available. The final sample included 845 individuals—377 men (45 percent) and 468 women (55 percent). The mean±SD age in 1987 was 48±17 years—43±16 for men and 52±17 for women. For the study period, the number of overall person-years was 9,690.

The distribution of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by sex in 1987 is reported in Table 1 . Most men were unmarried (58 percent), whereas only a third of women were unmarried (33 percent). Most patients were unemployed (64 percent of men and 78 percent of women). Approximately one-third of patients were admitted for the first time in 1987. Most patients of both sexes had schizophrenia disorders; affective psychoses and neurotic disorders and personality disorders were slightly more frequent among women; organic psychoses and substance use disorders were recorded for less than 7 percent of patients of both sexes.

|

SMRs by age and sex are shown in Table 2 . During the 16-year follow-up period, 322 patients (38 percent) died (144 men and 178 women). Mortality among psychiatric patients was significantly higher than in the general population—4.1 times higher for men and 2.5 times higher for women. Excess mortality was higher for patients younger than 45 years—for both sexes the rate was approximately 11 times as high.

|

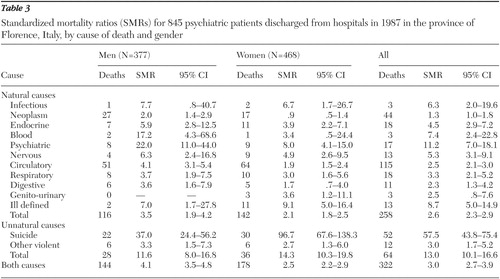

Table 3 shows SMRs by causes of death and by gender. Among psychiatric patients, mortality was significantly higher for each natural cause of death, except for infectious diseases among men and neoplasm, blood, and digestive diseases among women. Deaths resulting from circulatory diseases accounted for about 45 percent of all natural deaths for both sexes. Excess mortality from unnatural causes was much higher among psychiatric patients of both sexes. The suicide mortality rate among psychiatric patients was more than 50 times higher (SMR=57.5) than in the general population.

|

The percentage of unnatural deaths (data not shown) was larger for younger patients: among patients who were younger than 45 years in 1987, unnatural deaths accounted for 48 percent of deaths among men at follow-up and 45 percent of deaths among women. Among patients 45 years and older, the percentages were 12 and 18 percent, respectively.

Table 4 shows SMRs for natural and unnatural deaths by sex and time since date of discharge among patients who had a first admission in 1987. Overall, for natural deaths, SMRs remained almost stable during the first five years, with a decrease thereafter. For unnatural deaths, the decreasing trend began during the first years after discharge.

|

Results of a Poisson multivariate regression on SMRs are shown in Table 5 . For natural deaths, a significantly greater mortality risk was found for unemployed patients and those with organic psychoses or substance use disorders. For unnatural deaths, a significantly greater excess mortality risk was found among women and married patients. For both natural and unnatural deaths, excess mortality decreased with increasing age.

|

Discussion

Other studies

Comparisons with other studies are difficult. Most studies have not reported the distribution by age and gender of the sample; moreover, the length of the follow-up period and the case mix vary between studies.

Italy. In our cohort, individuals with mental illness had a higher mortality risk than the general population (SMR=3.0). This risk level is slightly lower than the one detected in a comparable Italian sample of 2,148 psychiatric patients (SMR=4.0) ( 33 ). Our study recruited patients admitted in 1987, and the study by Politi and colleagues ( 33 ) recruited patients admitted from 1978 to 1994. The first years after the Italian Psychiatric Reform Law became effective were a transitional period during which the quality of psychiatric patient care worsened because of delayed implementation of comprehensive outpatient services ( 38 , 39 ). Furthermore, because of the open cohort design, the recruitment period in the study by Politi and colleagues was very long; therefore, the proportion of patients in the first period after discharge, which we know to have a larger mortality risk, was larger than in our study.

On the other hand, the mortality risk in our study is higher than the risk found in another Italian study of 3,172 psychiatric patients (SMR= 1.63) ( 31 ). This Case Register study examined mortality among patients who had had at least one contact with a psychiatric service, whereas our sample consisted of patients who had had a hospital admission; thus the lower risk might be due to a lower severity of illness in that cohort, according to Goldberg and Huxley's model ( 40 ). A 1987 population study in south Verona that examined all levels of psychiatric illness found that the rate of receipt of outpatient psychiatric services was 4.0 per 1,000 persons per week, whereas the rate of receipt of inpatient care was much lower—.7 per 1,000 per week—because of the selection of more severe cases among inpatients ( 41 ).

Other countries. Studies of former psychiatric inpatients have found a risk that is one and a half to four times higher than in the general population. In the United States, Haughland and colleagues ( 15 ) found an SMR of 2.4 for men and 2.3 for women in a three-year follow-up study of 1,033 patients admitted to two public psychiatric hospitals from a single catchment area. Black and colleagues ( 8 ) calculated an SMR of 1.5 for men and 1.9 for women in a ten-year follow-up of 5,412 patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital affiliated with the University of Iowa. In a study of 289 patients four and a half years after admission to a psychiatric service of an urban general hospital, Curtis and associates ( 42 ) found an overall SMR of 2.3.

In Israel Zilber and colleagues ( 43 ) calculated an SMR of 2.3 in a five-year follow-up study of 16,147 patients who had undergone psychiatric hospitalization during the index year. In a study conducted in Norway after 1980, when the bed-to-population ratio was reduced by 50 percent, Hansen and associates ( 9 ) found an SMR of 3.2 for men and 2.4 for women in a 12-year follow up of 1,055 patients admitted to a public psychiatric hospital from a defined catchment area. In Finland Sohlman and Lehtinen ( 10 ) calculated an SMR of 4.7 for men and 3.2 for women in a follow-up study of 22,940 patients conducted four and a half years after discharge from all psychiatric hospitals in the index year. In Great Britain Prior and associates ( 44 ) found an SMR of 2.3 for males and 2.1 for females among 16,871 patients from two health districts entered in the psychiatric Case Register during a ten-year period. Patients were divided into two groups: inpatients who were hospitalized at least once during that period and outpatients.

Gender

In our study excess mortality was higher among men than among women, which is attributable to the much higher proportion of female patients older than 75 years. This observation highlights the importance of reporting age-stratified SMRs ( 45 ). Different age distributions for men and women may partly explain conflicting results of previous studies, which have found higher overall SMRs both for men ( 31 , 43 , 46 ) and for women ( 16 , 47 , 48 , 49 ).

Age

In our study excess mortality was found across all age groups but was especially high among both men and women younger than 45 years, which is a common finding ( 9 , 15 , 48 , 49 , 50 ). Hannerz and Borgå ( 51 ) suggested that among younger persons with psychiatric illness, excess mortality is mainly due to suicide and accidents, which may be related to the high level of vulnerability of the early phase of illness, when insight, treatment adherence, and coping skills may be poor. Furthermore, substance abuse is more prevalent among younger patients. Our findings confirm this thesis—unnatural deaths accounted for about 20 percent of deaths for the whole sample but about 50 percent among patients who were younger than 45 years at the beginning of the study period.

Time elapsed from discharge

Higher vulnerability in the earlier phases of psychiatric illness was also a factor in the decreasing rates of excess mortality from unnatural causes over time in our analysis of first admissions. In other studies of psychiatric patients, the highest level of excess mortality from unnatural causes has been observed within one or two years after discharge ( 48 , 52 ). Our study found that SMRs for deaths from natural causes were relatively stable during the first five years after discharge and decreased thereafter. A possible explanation is that the more susceptible patients die young and those who survive are more resistant and more similar to their peers in the general population.

Multivariate analysis of excess mortality

We used multivariate analysis to examine the independent effects of age, gender, employment status, civil status, and diagnosis on excess mortality from natural and unnatural causes. Age was significantly related to excess mortality from both natural and unnatural causes, confirming the results of the univariate analysis.

Moreover, excess mortality from natural causes was higher among unemployed patients and those with organic mental disorders. Unemployment can be considered as a proxy of socioeconomic status. Many studies have demonstrated an increased general mortality risk among low-income populations ( 53 , 54 , 55 ). Psychiatric illness and low socioeconomic status may be related to mortality because of poor health habits. Many studies have examined health behaviors and lifestyle factors in community populations as predictors of mortality, particularly for death from circulatory diseases ( 3 , 56 , 57 ). In regard to diagnosis, we found that the risk of death was at least twofold higher among patients with substance use disorders or organic psychoses than among those with schizophrenia. Studies of persons with mental disorders have consistently found that the highest mortality risk is related to organic factors or substance abuse ( 4 , 10 , 31 , 46 , 58 , 59 ).

Our study found that being a woman or being married had an independent effect on excess mortality from unnatural causes. Excess mortality from unnatural causes among women has been noted in other studies ( 8 , 15 , 19 , 43 ). These findings are probably attributable to the particularly low death rates from unnatural causes among women in the general population. Patients who were married in 1987 had a higher rate of death from unnatural causes than unmarried patients. We did not know patients' marital status at the end of the follow-up period. In the general population, mortality is known to be higher among those who have never been married ( 43 ), which has been a finding in some studies of psychiatric populations ( 19 , 47 ). However, conflicting findings in the literature ( 9 , 60 ) demonstrate how difficult it is to discriminate risks related to marital status.

Limitations

Our study did not include patients who died during hospitalization in 1987. Another limitation is our use of diagnosis at discharge. Such diagnoses are typically not made with standard methods, such as a structured diagnostic interview. The physician in charge of the patients formulated the diagnosis mainly on the basis of clinical interpretation.

A strength of our study is that it included all psychiatric patients who lived within a defined area and who were admitted to any of the eight psychiatric units that were active in the area in 1987.

Conclusions

In the context of a community-based psychiatric system with a low bed-to-population ratio, patients admitted to a psychiatric unit in a general hospital experienced higher rates of death resulting from both unnatural and natural causes than would be expected on the basis of rates in the general population. It is important to note that except for organic psychoses and substance abuse, excess mortality was not related to diagnosis but was found to be a general condition among psychiatric patients.

For deaths by unnatural causes, the highest excess mortality was among young patients within the first few years after discharge. Prevention measures may be required to avoid loss of contact with services and to promote an earlier follow-up in the community after discharge ( 61 ). The higher mortality rate from natural causes suggests a higher incidence of somatic diseases among psychiatric patients—possibly from poor health habits and side effects of psychotropic drugs and from difficulty seeking and obtaining help. Given the persistence of excess mortality by natural causes, even years after a first admission, it is important to improve prevention and treatment of somatic diseases among psychiatric patients from the onset of psychiatric illness and throughout treatment. Such improvements could be achieved by creating more responsive systems that promote continuity of care and that take into consideration the biological, psychological, and social complexity of mental illness. In particular, psychiatrists—together with general practitioners—should pay more attention to prevention, assessment, early diagnosis, and treatment of their patients' somatic diseases. Improvements in this area require better integration between different components of the health system.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Adele Seniori Costantini, M.D., for ongoing support and officials at the Tuscan Mortality Registry for technical contributions.

1. Helgason L: Psychiatric services and mental illness in Iceland: incidence study (1966-1967) with 6-7 year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 268(suppl):1-140, 1977Google Scholar

2. Martin RL, Cloninger CR, Guze SB, et al: Mortality in a follow-up of 500 psychiatric outpatients: I. total mortality. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:47-54, 1985Google Scholar

3. Engberg M: Mortality and suicide rates of involuntarily committed patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:35-40, 1994Google Scholar

4. Hewer W, Rössler W, Fätkenheuer B, et al: Mortality among patients in psychiatric hospitals in Germany. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 91:174-179, 1995Google Scholar

5. Räsänen S, Hakko H, Viila K et al: Excess mortality among long-stay psychiatric patients in Northern Finland. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:297-304, 2003Google Scholar

6. Harris EC, Barraclough B: Excess mortality of mental disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:11-53, 1998Google Scholar

7. Black DW, Warrack G, Winokur G: The Iowa Record-Linkage Study: III. excess mortality among patients with functional disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:82-88, 1985Google Scholar

8. Black DW, Warrack G, Winokur G: Excess mortality among psychiatric patients: the Iowa Record-Linkage Study. JAMA 253:58-61, 1985Google Scholar

9. Hansen V, Arnesen E, Jacobsen BK: Total mortality in people admitted to a psychiatric hospital. British Journal of Psychiatry 170:186-190, 1997Google Scholar

10. Sohlman B, Lehtinen V: Mortality among discharged psychiatric patients in Finland. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 99:102-109, 1999Google Scholar

11. Mortensen PB, Juel K: Mortality and causes of death in first admitted schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 163:183-189, 1993Google Scholar

12. Giel R, Dijk S, van Weerden-Dijkstra JR: Mortality in the long-stay population of all Dutch mental hospitals. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 57:361-368, 1978Google Scholar

13. Brook OH: Mortality in the long-stay population of Dutch mental hospitals. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 71:626-635, 1985Google Scholar

14. Licht RW, Mortensen PB, Gouliaev G, et al: Mortality in Danish psychiatric long-stay patients, 1972-1982. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 87:336-341, 1993Google Scholar

15. Haughland G, Craig TJ, Goodman AB, et al: Mortality in the era of deinstitutionalization. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:848-852, 1983Google Scholar

16. Wood JB, Evenson RC, Cho DW, et al: Mortality variations among public mental health patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 72:218-229, 1985Google Scholar

17. Koranyi EK: Fatalities in 2,070 psychiatric outpatients: preventive features. Archives of General Psychiatry 34:1137-1142, 1977Google Scholar

18. Sturt E: Mortality in a cohort of long-term users of community psychiatric services. Psychological Medicine 13:441-446, 1983Google Scholar

19. Martin RL, Cloninger CR, Guze SB, et al: Mortality in a follow-up of 500 psychiatric outpatients: II. cause specific mortality. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:58-66, 1985Google Scholar

20. Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Rozal GPM, et al: Psychiatric status and 9-year mortality data in the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:716-721, 1994Google Scholar

21. Fichter MM, Rehm J, Elton M, et al: Mortality risk and mental disorders: longitudinal results from the Upper Bavarian Study. Psychological Medicine 25:297-307, 1995Google Scholar

22. Target Project: Safeguarding of mental health, 1998-2000 [in Italian]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, Serie Generale 274:4-13, 1999Google Scholar

23. Cozza M, Laurito S, Napolitano G.M, Provenzan R: Psychiatric Care in Italy. Regulation and Services Diffusion Throughout the Territory [in Italian]. Rome, Italian Institute of Social Medicine, 1996Google Scholar

24. Cooper B: Public-health psychiatry in today's Europe: scope and limitations. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:169-176, 2001Google Scholar

25. Fioritti A, Lipparini D, Melega V: Mortality of long-term psychiatric inpatients: retrospective study on a cohort of long-term patients in the Psychiatric Hospital of Bologna, Italy [in Italian]. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 3:107-114, 1994Google Scholar

26. Ballone E, Contini G: Mortality of the psychiatric patient: retrospective study on a cohort of long-term patients in the Psychiatric Hospital of Reggio Emilia [in Italian]. Epidemiologia e Prevenzione 50:56-58, 1992Google Scholar

27. Cecere F, Arca M, Pallini S, et al: Mortality rates among psychiatric patients, during and after the "psychiatric reform," in the area of Rome (Italy) [in Italian]. Annali dell' Istituto Superiore di Sanità 28:523-526, 1992Google Scholar

28. Bacigalupi M, Cecere F, Arcà M, et al: Mortality of in-patients in public psychiatric hospitals of Lazio: first results [in Italian]. Epidemiologia e Prevenzione 35:11-16, 1988Google Scholar

29. D'Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Negri E: Mortality in long-stay patients from psychiatric hospitals in Italy: results from the Qualyop Project. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:385-389, 2003Google Scholar

30. Valenti M, Necozione S, Busellu G: Mortality in psychiatric hospital patients: a cohort analysis of prognostic factors. International Journal of Epidemiology 26:1227-1235, 1997Google Scholar

31. Amaddeo F, Bisoffi G, Bonizzato P, et al: Mortality among patients with psychiatric illness: a ten-years case register study in an area with a community-based system of care. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:783-788, 1995Google Scholar

32. Lesage AD, Trapani V, Tansella M: Excess mortality by natural causes of Italian schizophrenic patients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Neurological Science 239:361-365, 1990Google Scholar

33. Politi P, Piccinelli M, Klersy C, et al: Mortality in psychiatric patients 5 to 21 years after hospital admission in Italy. Psychological Medicine 32:227-237, 2002Google Scholar

34. Rossi Prodi P: Mental Health Florence, 2002 Report [in Italian]. Florence, Florence Public Health District, 2002Google Scholar

35. Deaths by cause in 2002 [in Italian]. Florence, Region of Tuscany, Statistics Department, 2004Google Scholar

36. Breslow NE, Day NE: Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Lyon, France, IARC Scientific Publications, 1987Google Scholar

37. STATA Statistical Software: Release 8.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2003Google Scholar

38. Williams P, De Salvia D, Tansella M: Suicide, psychiatric reform, and provision of psychiatric services in Italy. Social Psychiatry 27:89-95, 1986Google Scholar

39. Fioritti A, Lo Russo L, Melega V: Reform said or done? The case of Emilia-Romagna within the Italian psychiatric context. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:94-98, 1997Google Scholar

40. Goldberg DP, Huxley P: Mental Illness in the Community. London, Tavistock, 1980Google Scholar

41. Tansella M, Williams P: The spectrum of psychiatric morbidity in a defined geographical area. Psychological Medicine 19:765-770, 1989Google Scholar

42. Curtis JL, Millman EJ, Struening E, et al: Deaths among former psychiatric inpatients in an outreach case management program. Psychiatric Services 47:398-402, 1996Google Scholar

43. Zilber N, Schufman N, Lerner Y: Mortality among psychiatric patients: the group at risk. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 79:248-256, 1989Google Scholar

44. Prior P, Hassall C, Cross KW: Causes of death associated with psychiatric illness. Journal of Public Health Medicine 18:381-389, 1996Google Scholar

45. Rothman KJ, Greenland S: Modern Epidemiology, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1998Google Scholar

46. Lawrence D, Jablenski AV, Holman CDJ, et al: Mortality in Western Australian psychiatric patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:341-347, 2000Google Scholar

47. Casadebaig F, Quemada N: Mortality in psychiatric inpatients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 79:257-264, 1989Google Scholar

48. Black DW: Iowa Record-Linkage Study: death rates in psychiatric patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 50:277-282, 1998Google Scholar

49. Baxter DN: The mortality experience of individuals on the Salford Case Register: I. all-cause mortality. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:772-779, 1996Google Scholar

50. Corten P, Ribourdouille M, Dramaix M: Premature death among outpatients at a community mental health center. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1248-1251, 1991Google Scholar

51. Hannerz H, Borgå P: Mortality among persons with a history as psychiatric inpatients with functional psychosis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:380-387, 2000Google Scholar

52. Osby U, Correia N, Brandt L, et al: Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm County, Sweden. Schizophrenia Research 45:21-28, 2000Google Scholar

53. Haan M, Kaplan G, Camacho T: Poverty and health: prospective evidence from the Alameda County study. American Journal of Epidemiology 125:989-998, 1987Google Scholar

54. Morris JN: Social inequality undiminished. Lancet 1:87-90, 1979Google Scholar

55. Dayal N, Chiu CY, Sharvar R: Ecologic correlates of cancer mortality patterns in an industrialized urban population. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 73:565-574, 1984Google Scholar

56. Kamara SG, Peterson PD, Dennis JL: Prevalence of physical illness among psychiatric inpatients who die of natural causes. Psychiatric Services 49:788-793, 1998Google Scholar

57. Wiley J, Camacho T: Life-style and future health: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Preventive Medicine 9:1-21, 1980Google Scholar

58. Chen WJ, Huang YJ, Yeh LL, et al: Excess mortality of psychiatric inpatients in Taiwan. Psychiatric Research 62:239-250, 1996Google Scholar

59. Zubenko GS, Mulsant, Sweet RA, et al: Mortality of elderly patients with psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1360-1368, 1997Google Scholar

60. Rorsman B: Mortality among psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 50:354-75, 1974Google Scholar

61. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T et al: Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey. British Medical Journal 318:1235-1239, 1999Google Scholar