Innovations: Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Measuring Outcomes of Real-World Youth Psychotherapy: Whom to Ask and What to Ask?

Service providers are increasingly required by managed care organizations and public funding agencies to monitor client progress and demonstrate treatment effectiveness. Therefore, the measurement of psychotherapy outcomes has become an important issue for all stakeholders—funders, administrators, providers, consumers, and researchers. However, despite the pressure on providers to assess client outcomes, there has been surprisingly little discussion about the methodological challenges and limitations of outcome measurement, specifically the implications of selecting outcome indicators.

Outcome measurement is particularly complex for child and adolescent services because of the well-known discrepancies between the reports of youths and their parents about symptom severity and functional impairment. It is essential for all stakeholders in youth services to appreciate the complexities and limitations of outcome measurement, tempering conclusions so as not to rush to overly simplistic and thus invalid judgments about the effectiveness—or ineffectiveness—of care.

Although research on treatment outcomes has historically defined effectiveness as a decrease in symptom severity, there have been calls for an expansion of the range of outcome indicators. For example, Hoagwood and colleagues ( 1 ) highlighted the importance of a multidimensional conceptualization of outcomes for youth mental health services, identifying five outcome domains: symptoms, functional impairment, consumer perspectives, environment, and systems. Despite the appeal of a multidimensional conceptualization of outcome measurement, which includes both multiple domains and multiple informants for each domain, such a model is methodologically complex and poses significant challenges to implementation. There may be important differences in an individual stakeholder's perception of change across outcome constructs. Thus the answer to the seemingly straightforward question, "Did the patient improve?" is a potentially unsatisfying, "It depends on who was asked and what was asked."

Most analyses of change in outcomes for youths in psychotherapy are conducted in the context of clinical interventions research. Such research usually takes place in specialized, research-oriented clinical settings with selected providers and selected patients. We know, however, that providers and patients in community-based care often differ significantly from those who participate in research-based treatment. Furthermore, the organizational contexts of community-based services may be very different from those in highly structured research settings. To gain understanding of the challenges and implications of outcome measurement for providers in the real world, it is essential to examine outcome measurement in usual care and community-based clinical settings, with patients and providers from nonresearch samples.

At our center, we have pursued a program of research that examines methodological challenges of outcome measurement in community-based treatment settings. In this column we summarize a small-scale study that illustrates the complexities in interpreting change in multidimensional outcome measures for youths receiving community-based outpatient psychotherapy.

Demonstration of measurement complexities

To demonstrate the complexities associated with outcome measurement in real-world settings, we examined change in standardized outcome indicators for youths from 112 families who entered usual-care youth psychotherapy in either of two publicly funded outpatient mental health clinics in San Diego County. The purpose of this study was to identify patients who clearly improved on the basis of individual outcome measures and to determine whether there was agreement between informants (youth and parent) and across outcome domains (symptoms, functioning, and family environment) in terms of whether the youth would be classified as having improved. The youths who participated in this study, which was conducted between 2000 and 2002, included 69 boys and 43 girls between the ages of 11 and 17 who were diagnostically and ethnically diverse and representative of the patient population receiving publicly funded treatment in the region. Forty-nine (44 percent) self-identified as Caucasian, 16 (14 percent) as Latino, 16 (14 percent) as African American, and 30 (27 percent) as multiethnic or another ethnicity.

Forty of the youths (36 percent) were diagnosed as having attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, 28 (25 percent) as having a disruptive behavior disorder, 55 (49 percent) as having a mood disorder, and 12 (11 percent) as having an anxiety disorder. (Some youths had more than one diagnosis.) A majority of the youths were from racial or ethnic minority groups, lived in single-parent households, and had a family annual income of less than $45,000. Participants were compensated minimally for their time, and the study was approved by multiple human subjects protection committees (University of California, San Diego; Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego; and the San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services).

Treatment providers represented a number of disciplines (psychiatry, psychology, marriage and family therapy, and social work) and various levels of experience. A majority of the clinicians identified their primary theoretical orientation as eclectic or family systems. No standard treatment protocol or theory of change drove the treatment, as might be found in a research-based intervention study, because the objective of the study reported here was to examine outcomes of usual care.

When the youths entered treatment, a number of commonly used standardized measures were administered to the families. These measures represent three of the outcome domains discussed by Hoagwood and colleagues ( 1 ). They included measures of symptoms (Child Behavior Checklist and Youth Self Report), functioning (Vanderbilt Functioning Index), and family environment (Family Relationship Index). These measures were readministered after six months, regardless of whether the youth remained in treatment.

To represent the youths who showed clear positive change on each outcome measure, a difference score was calculated for each measure by subtracting the six-month follow-up score from the baseline score. Participants whose difference score on an individual measure was greater than one standard deviation from the sample's mean difference score were classified as having clearly improved on that measure. The extent of agreement between youths' and parents' reports for patients who were classified as having improved on the basis of either report was examined for each domain (symptoms, functioning, and environment) to illustrate the extent of divergence and convergence in outcome measurement.

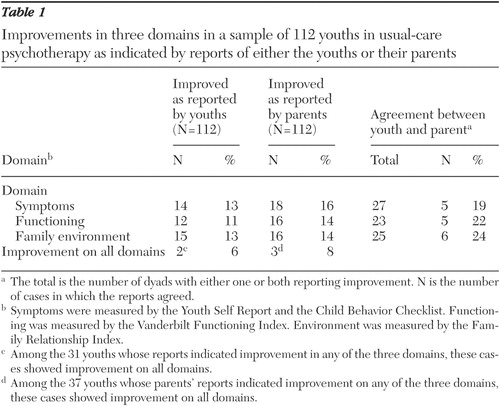

The results of this study demonstrate the complexity of assessing the effectiveness of care. On the basis of the definition of improvement given above, the proportion of youths who improved on each domain, as separately reported by parents and by youths on standard measurement tools, ranged from 11 percent to 16 percent. As Table 1 shows, 27 youths were classified as having improved in the symptom domain as indicated by either the youth's or the parent's report; however, for only five youths (19 percent) did both the youth and parent report improvement in this domain. Similarly, the agreement was 22 percent and 24 percent for the functioning and family environment domains, respectively.

|

Among the 31 youths whose reports indicated improvement in any of the three domains, only two (6 percent) improved across all domains, six (19 percent) improved in two domains (data not shown), and the remaining 23 (74 percent) improved on one domain (data not shown). For the 37 youths whose parents' reports indicated improvement on any of the three domains, only three (8 percent) improved across all domains, seven (19 percent) improved on two domains (data not shown), and the remaining 27 (73 percent) improved on one domain (data not shown). Overall, minimal agreement was found between the reports of youths and parents on each outcome domain, and agreement across the three domains was also minimal. That is, youths who clearly improved on a measure according to the report of either the youth or the parent were seldom classified as having improved on that measure by the other member of the dyad, and youths who were found to have improved in one outcome domain were seldom classified as having improved on the other domains.

Conclusions and implications

These findings support the notion that measuring one domain of outcome provides a limited perspective on the impact of care ( 1 ). Very different groups of youths would be classified as having improved depending on the outcome indicators that a program selected for purposes of program evaluation or utilization review. Thus determining the "bottom line" in terms of the impact or effectiveness of care appears very challenging. The findings further suggest that previous studies of usual-care youth psychotherapy may have underestimated the impact of treatment because the studies relied on a limited the number of outcome domains or informant perspectives, especially given the current focus on multisystemic treatments that target multiple determinants of youths' mental health problems ( 2 ).

This work contributes to the knowledge base in the area of outcome measurement by examining the extent of agreement between youths' and parents' reports of improvement and by identifying youths who improved on well-established, standardized measures, rather than looking at cross-sectional correlations between informants' reports. However, the outcome story is much more complex than the two informants and three domains of functioning highlighted in this example. To truly measure the impact of youth psychotherapy, a number of other informants (for example, teachers and peers), outcome domains (for example, peer relationships), and developmental status indicators would provide a more comprehensive, meaningful, and—paradoxically—confusing picture.

This relatively simple study highlights a fundamental dilemma, namely, determining the impact of mental health care depends on who is asked about what. The complexities in measuring and interpreting the impact of community-based youth psychotherapy, apparent in the lack of overlap between informants and across domains in this study, have important implications for policy and research methods. Managed care organizations and public funding sources must critically review what is meant by "improvement" (and lack thereof) in usual-care psychotherapy and must exercise caution when selecting and interpreting outcome indicators that may have significant fiscal or policy implications for providers.

Well-intentioned efforts to empirically examine the effectiveness of mental health services may be myopic and overly simplistic in drawing conclusions based on limited measurement of outcomes. Overly simplistic assessments of treatment effectiveness likely contribute to the disconnect between research and practice, in that practitioners may feel frustrated by narrowly defined measurement of treatment outcomes. Providers' resistance to outcome measurement may often be attributed to protective defensiveness, but valid skepticism about the limitations of current outcome measurement methods and interpretation of findings likely contributes to such resistance. Lack of forthright discussion of the limitations of outcome measurement risks a reversal of the clear gains that have been made in increasing empirically based accountability for mental health service delivery in the past decade.

Improved collaboration between researchers, practitioners, and consumers in identifying and prioritizing key outcome indicators is needed to increase the ecological validity and meaningfulness of outcome measurement. Corresponding methodological and technological work is needed to develop and refine feasible, reliable, and valid methods of multidimensional outcome measurement. Multidimensional methods of outcome measurement need to be further developed and refined to provide guidance on how to interpret discrepancies across informants and outcome domains. Work by esteemed research groups is ongoing in these areas, but in the meantime, confidence in our ability to definitively and meaningfully measure the impact of mental health care should be tempered.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants K01-MH-01544, R01-MH-66070, and R01-MH-066070-S1 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Caroline Lewczyk Boxmeyer, Ph.D., Elaine Gabayan, M.A., and Katherine Tsai, B.A., for their contributions.

1. Hoagwood K, Jensen PS, Petti T, et al: Outcomes of mental health care for children and adolescents: I. a comprehensive conceptual model. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1055-1063, 1996Google Scholar

2. Jensen PS, Hoagwood K, Petti T: Outcomes of mental health care for children and adolescents: II. literature review and application of a comprehensive model. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1064-1077, 1996Google Scholar