Incentive Payments for Attendance at Appointments for Depression Among Low-Income African Americans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of nominal incentive payments on attendance at therapy appointments among 50 low-income African Americans with depression. METHODS: Attendance at therapy appointments for depression without incentive was tracked for 12 weeks, followed by tracking of 12 weeks during which $10 payments were given at regular appointments and a third 12-week period of appointments without payments. RESULTS: After adjustment for rescheduling, 54 percent of patients had better adherence when payments were attached to appointments, and an additional 14 percent continued with perfect attendance throughout this second period. In the third period, when payments were no longer made, 66 percent had a decline in adherence. Less rescheduling was also observed during the incentive period. CONCLUSION: Incentive payments have the potential to improve appointment adherence among low-income African Americans with depression.

The provision of optimal depression treatment raises many challenges and barriers, such as access and adherence to therapy for vulnerable populations. For example, African Americans tend to be underrepresented in outpatient treatment populations but overrepresented in emergency and inpatient settings (1). As a result, low-income African Americans and patients with Medicaid insurance are less likely than their white, privately insured counterparts to receive continuous therapy for mental health conditions (2). This dynamic of episodic care in emergency and inpatient settings is believed to be rooted more in poverty, attitudes about seeking help, and a lack of community support than in clinician bias in diagnosis and treatment (3).

Mutable barriers to outpatient mental health treatment among African Americans could be most proximally related to financial and logistic problems in keeping appointments, beyond that of the direct cost of clinical services. Previous studies of persons with non-mental health conditions have shown dramatic differences in adherence rates when patients were offered nominal payments for adherence (4,5,6). When drug users were administered tuberculosis tests, 33 percent (33 of 100) returned for skin test readings when no payments or other interventions were offered, 34 percent (34 of 99) returned when they were provided with motivational education, and 93 percent (186 of 200) returned when they were offered $10 to do so (6). In a similar study, 84 percent of patients (69 of 82) with tuberculosis attended follow-up appointments when offered $5, compared with 53 percent (42 of 79) of those who were not offered payments (4). When pregnant teenage mothers were asked to attend weekly peer-support groups, 58 percent of 107 mothers who were offered $7 to attend each session participated at least once, compared with only 9 percent of 24 mothers who were not offered payments (5).

We found no previous studies of similar incentives in adult mental health treatment. Using an interrupted time-series trial, we evaluated the effect of nominal payments to offset incidental expenses of attending scheduled therapy appointments for low-income African Americans with depressive disorders and assessed self-perceived barriers to attendance.

Methods

We enrolled patients who had billing diagnoses of major depression or depression not otherwise specified at a clinic affiliated with a university mental health center. The three master's-level therapists at the clinic provide eclectic psychotherapy to a predominately low-income African-American population in concert with psychiatrist-supervised pharmacotherapy. Sixty patients who were in active treatment (with a median treatment duration of two years) were referred to the study by therapists. Of these, 58 were eligible, and 54 enrolled after providing informed consent. Approval was obtained from the university's institutional review board. Data collection began in March 2003 and ended in August 2004.

The study followed an interrupted time-series design. Adherence without incentive was tracked during an initial 12-week period, followed by a second 12 weeks of $10 payments at the conclusion of each regularly scheduled appointment (usually weekly, but solely at the therapist's discretion), and a third 12 weeks of assessment of adherence without payments. The 36-week follow-up began at enrollment for each individual.

A research assistant informed the study participants of the dates for the incentive period at enrollment and administered a baseline survey on attitudes and barriers to care, associated out-of-pocket costs, and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Possible PHQ-9 scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The research assistant logged the expected date of each scheduled appointment, and therapists validated attendance. Four participants discontinued care at the clinic before incentives began. At the end of follow-up, 44 participants completed an exit survey that assessed changes in barriers to adherence and attitudes toward care, and administration of the PHQ-9 was repeated. Participants received $10 on completion of each survey.

Appointment adherence was calculated on both an individual and an aggregate basis. Adherence was calculated as the proportion of scheduled appointments kept. The expected date of the next appointment was recorded, and documentation of rescheduling of appointments was collected. Thus we were able to calculate rates of rescheduling separate from no-shows. We used McNemar's test to examine differences in group proportions across study periods, and the Sign test to examine differences in individual adherence.

Results

The mean±SD age of the 54 participants was 46±9.6 years; 46 participants (85 percent) were female, 52 (96 percent) were African American, and 45 (83 percent) had children (although not all children still lived at home). The mean baseline PHQ-9 score was 13.6±6.1, indicating on average a significant level of depression. Forty participants (74 percent) traveled to appointments by bus and described transportation expenses that study payments would cover (the median one-way fare was $1.75, with a range of $0 to $4.50). At baseline, 37 participants (69 percent) reported having missed appointments in the past. Forty-two (78 percent) endorsed the consistent effectiveness of therapy, and 28 (52 percent) reported that they would attend a session for $10 even if the therapy was not helpful.

At baseline, only four respondents (7 percent) identified transportation as a reason for missing appointments; 15 (28 percent) cited physical or unspecified health problems; seven (13 percent) cited mental health symptoms; and 13 (24 percent) cited competing obligations, of which approximately one-third were related to child care. However, no participant reported at baseline paying for child care to attend an appointment, and none identified work-related barriers. Only one person (2 percent) reported an out-of-pocket payment ($3) for the clinic visit.

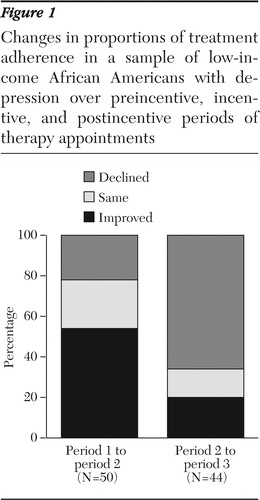

Figure 1 shows the distribution of changes in individual appointment adherence between periods, adjusted for rescheduling. As illustrated, 27 of 50 participants (54 percent) had improved adherence during the incentive period; 12 participants (24 percent) had unchanged adherence, seven of whom continued with perfect attendance; and 11 (22 percent) had reduced adherence. These results represent a significant increase in adjusted adherence for individuals during period 2 (Sign statistic [M]=8, p<.014), with a mean absolute improvement of 6±21 percent. In keeping with an aggregate decline in the postincentive period, 29 of 44 participants (66 percent) had a decline in individual adherence between periods 2 and 3 (M=-10, p<.002).

The sample as a whole kept 260 of 391 appointments (66 percent) made during period 1. After adjustment for rescheduling, aggregate adherence was 79 percent (N=260 of 328) in period 1. Payments during period 2 were associated with a significant increase in adjusted aggregate adherence to 86 percent (N=342 of 396; McNemar statistic [S]=135.1, df=1, p<.001). In addition, there was a decrease in rescheduling from 16 percent of all period 1 appointments (63 of 391) to 10 percent (42 of 438) during period 2 (S=241.6, df=1, p<.001). In period 3, adjusted adherence decreased from 86 percent to 69 percent (153 of 221), coincident with the discontinuation of payments (S=183.1, df=1, p<.001). Compared with period 2, rescheduling increased slightly but significantly in period 3 to 11 percent (27 of 248; S=121.8, df=1, p<.001).

At study exit, the mean PHQ-9 score was 11.8±6.5. Mean improvement in scores between baseline and exit was 2.3±6.5. When asked to again identify barriers to attendance, no participants identified transportation; 13 of 44 participants (30 percent) cited physical or unspecified health problems, two (5 percent) cited mental health symptoms, and 11 (25 percent) cited competing obligations, of which, again, one-third were related to child care. Three participants (7 percent) reported paying for child care, at a mean cost of $18±10 per episode. One participant (2 percent) reported an out-of-pocket payment ($120) for the visit, and one reported taking uncompensated time off from work to keep the appointment. Only 15 participants (34 percent) believed that the payments made it easier to attend therapy.

We examined survey data to identify any associations with individual adherence. Older age was significantly correlated with superior attendance in period 1 (r=.35, p<.001) and period 2 (r=.34, p<.02). A greater percentage improvement in PHQ-9 scores was also correlated with higher attendance in period 1 (r=.38, p<.012) and period 2 (r=.38, p<.011). Although participants were evenly distributed at baseline in terms of whether they would attend therapy simply for the incentive, this response was not significantly associated with adherence.

Discussion

We demonstrated that nominal payments can both improve adherence and decrease the prevalence of rescheduling among low-income African Americans with depression. Transportation and child care expenses were self-perceived barriers that payments could defray. However, the prevalence of these barriers was lower than nonfinancial barriers, such as health concerns.

Appointment adherence was documented to be a problem in this setting, with only 66 percent of all appointments kept. The figure is higher (79 percent) if one adjusts for rescheduling, but the prevalence of deferring appointments in this manner was noteworthy. Being older was associated with greater adherence, even before the incentive period, which is consistent with previous studies of appointment keeping (7).

The magnitude of the incentive effect was lower than that found in many previous studies. A key difference was our aim to motivate serial behavior rather than the keeping of a single appointment. Several studies that incorporated incentives suggest a more modest effect on adherence to a series of appointments. Morisky and colleagues (8) demonstrated net absolute improvements in adherence to tuberculosis treatment visits of 7 percent (N=89; patients with active tuberculosis) and 17 percent (N=117; patients undergoing chemoprophylaxis) over six- to 12-month follow-up using a multifactorial incentive that included $5 or $10 payments. Laken and Ager (9) found no effect of incentives on adherence to prenatal care appointments among 205 low-income women, 104 of whom were randomly assigned to receive a $5 gift certificate at each visit.

The survey data illustrate that barriers to adherence may not be solved simply by providing a nominal payment to reduce the cost of attendance. For example, very few participants paid for child care, but approximately 10 percent consistently noted in open-ended questions that child care was a significant barrier. Given the patients' modest incomes, there may be an economic barrier that a nominal payment cannot readily solve, because the problem is taken care of through bartering child care rather than by paying for services. Time may be a more proximate barrier than money given that a majority of the study participants consistently stated that the current incentive program did not enhance their ability to keep their appointments.

Our single-site pilot study had limitations. The time course of individual patients' depression varied, and survey data were obtained only at study entry and exit. A larger, randomized study in diverse settings and populations would provide stronger, more generalizable evidence of incentive payment effects. Adherence in period 1 may have been influenced by anticipation of incentives in the subsequent period. Finally, there may be barriers to instituting incentives at a policy level, including varying opinions on the acceptability of patient payments (10).

Conclusions

Reducing the net cost of attendance through nominal payments can improve adherence and decrease rescheduling of visits among low-income African Americans with depression. However, barriers to attendance are complex. Research suggests that enhancing adherence to proven treatments is central to improving care in this population. Lowering the cost of treatment can help improve outcomes, but there are challenges to instituting policies to facilitate treatment adherence. In particular, difficulties remain in constructing incentives that are appropriate in magnitude, sufficiently individualized to diverse circumstances, and acceptable and practical at a policy level. Additional studies are needed to describe and test solutions to these challenges. We look forward to building on these findings to improve adherence to evidence-based mental health care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Staunton Farm Foundation and by grant K23 MH-01879 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Post is affiliated with the department of medicine and the department of psychiatry of the University of Pittsburgh, Center for Research on Health Care, 230 McKee Place, Suite 600, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Cruz is with the department of psychiatry of the University of Pittsburgh. Dr. Harman is with the department of health services research, management, and policy of the University of Florida in Gainesville.

Figure 1. Changes in proportions of treatment adherence in a sample of low-income African Americans with depression over preincentive, incentive, and postincentive periods of therapy appointments

1. Snowden LR, Cheung FK: Use of inpatient mental health services by members of ethnic minority groups. American Psychologist 45:347–355,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Melfi C, Croghan T, Hannah M: Access to treatment for depression in a Medicaid population. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 10:201–215,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Snowden L: Inpatient mental health use by members of ethnic minority groups, in Cross Cultural Psychiatry. Edited by Herrera J, Lawson W, Smerck J. Chichester, England, Wiley, 2001Google Scholar

4. Pilote L, Tulsky JP, Zolopa AR, et al: Tuberculosis prophylaxis in the homeless: a trial to improve adherence to referral. Archives of General Internal Medicine 156:161–165,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Stevens-Simon C, Dolgan JI, Kelly L, et al: The effect of monetary incentives and peer support groups on repeat adolescent pregnancies: a randomized trial of the Dollar-a-Day program. JAMA 277:977–982,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Malotte CK, Rhodes F, Mais KE: Tuberculosis screening and compliance with return for skin test reading among active drug users. American Journal of Public Health 88:792–796,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Oppenheim GL, Bergman JJ, English EC: Failed appointments: a review. Journal of Family Practice 8:789–796,1979Medline, Google Scholar

8. Morisky DE, Malotte CK, Choi P, et al: A patient education program to improve adherence rates with antituberculosis drug regimens. Health Education Quarterly 17:253–267,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Laken MP, Ager J: Using incentives to increase participation in prenatal care. Obstetrics and Gynecology 85:326–329,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Giuffrida A, Torgerson DJ: Should we pay the patient? Review of financial incentives to enhance patient compliance. British Medical Journal 315:703–707,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar