High-Cost Use of Second-Generation Antipsychotics Under California's Medicaid Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The high costs associated with second-generation antipsychotic medications raise concerns that prior-authorization restrictions may be implemented to restrict use. This study assessed patterns of antipsychotic use to identify uses that are associated with high economic cost but for which there is no documented efficacy. METHODS: California Medicaid fee-for-service pharmacy claims were analyzed from May 1999 through August 2000 for patients who received risperidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine. RESULTS: Of the 116,114 patients who received at least one of these agents, 4.1 percent received a combination regimen. Polypharmacy was the most expensive form of second-generation antipsychotic use, costing up to three times more per patient than monotherapy. CONCLUSION: Restricting polypharmacy may reduce costs and prevent the need for prior-authorization restrictions.

Prescription rates for first-line second-generation antipsychotics (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole) have increased enormously over the past several years, whereas those for first-generation agents have steadily declined, according to 2002 data from IMS Health. The absence of extrapyramidal side effects with these agents, combined with their potential efficacy for negative and cognitive symptoms, has made them valuable resources in the treatment of psychosis (1).

However, second-generation antipsychotics are among the most expensive drugs available to treat psychiatric illness. In 2002, olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine were the first, second, and fifth most costly of all 1,900 covered drugs in the fee-for-service sector of Medi-Cal, California's Medicaid program. Furthermore, the total pharmacy costs in 2002 for olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone were greater than the costs of the bottom 1,736 drugs combined.

The increasingly high costs of second-generation antipsychotics within Medi-Cal have created a threat that formulary restrictions will be implemented, most likely through denial of access to certain agents solely on the basis of economic factors. Such restrictions are already being seen in other states, as well as in other departments of the California state government. For example, the Kentucky and West Virginia programs have removed olanzapine from their preferred-drug lists. The California Departments of Corrections, Developmental Disabilities, Mental Health, and Youth Authorities have assembled a committee that is creating a cost-based tier system for selecting second-generation antipsychotics, such that the less expensive tier 1 drugs must be tried and found ineffective or intolerable before the more expensive tier 2 drugs can be used.

The threat of formulary restrictions prompted Medi-Cal's drug use review board to conduct a retrospective analysis of utilization patterns for first-line second-generation antipsychotics to identify uses for which there is no evidence of effectiveness but that are associated with particularly high costs. Recent reviews of available data demonstrated that neither the effectiveness nor the safety of combinations of antipsychotics (polypharmacy) has been established (2,3). Two recent double-blind studies of clozapine-risperidone poly-pharmacy had contradictory results (4,5). Despite the lack of controlled data, antipsychotic polypharmacy occurs commonly in clinical practice, in both inpatient (6) and outpatient (7) settings. If such practices are frequent within Medi-Cal, then reducing them and replacing them with practices for which there is more evidence and that are less costly could lead to cost savings that would make it possible to maintain an open formulary, allowing clinicians to choose the optimal therapy for each individual patient.

The purpose of this study was to assess patterns of antipsychotic use to identify uses associated with high economic cost but for which there is no documented efficacy.

Methods

Medi-Cal pharmacy claims from May 1, 1999, through August 31, 2000, were analyzed to identify outpatients who had received at least one of the three second-generation antipsychotics—risperidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine—for at least 60 days out of any 75-day period. (At that time neither ziprasidone nor aripiprazole was on the formulary.) The primary study population was then broken down into three groups: patients who had received only one second-generation antipsychotic during the 16-month period (group 1), patients who had received more than one second-generation antipsychotic for no more than 59 out of 75 days concomitantly (group 2), and patients who had received more than one of the three drugs simultaneously for at least 60 days out of any 75-day period (group 3).

The population that received any antipsychotic (first- or second-generation) during the 16-month period was also evaluated for polypharmacy. The criteria for concomitant use were the same as for group 3—that is, at least two agents had to have been used for at least 60 days out of any 75-day period.

The cost analysis was based on the amount paid per prescription within Medi-Cal.

Results

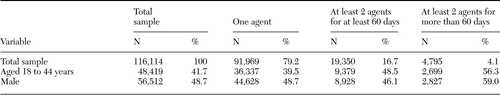

The breakdown of the total population into groups 1, 2, and 3 is shown in Table 1, along with the gender and age compositions of the groups. A total of 116,114 patients received at least one of the three second-generation antipsychotics for at least 60 out of 75 days between May 1, 1999, and August 31, 2000. A total of 91,969 of those patients (79.2 percent) received only one agent during the study period; 19,350 (16.7 percent) received at least two agents with no period of concomitant use greater than 59 out of 75 days, and 4,795 (4.1 percent) received at least two agents simultaneously for at least 60 out of 75 days.

The total amount paid (pharmacy costs) through Medi-Cal for patients who received a second-generation antipsychotic was $309,644,640. Group 1 accounted for $219,123,216 (70.8 percent) of the total pharmacy costs, group 2 accounted for $54,380,659 (17.6 percent), and group 3 accounted for $36,134,508 (11.7 percent). The mean amount paid per patient for group 1 was $2,382, for group 2 was $2,810, and for group 3 was $7,536.

Secondary analysis showed that 218,731 patients received either a first-generation or a second-generation antipsychotic for at least 60 days out of any 75-day period during the 16 months. Of these, 21,332 (9.8 percent) received at least two agents concomitantly for at least 60 out of 75 days.

Discussion

Second-generation antipsychotics are the most expensive drug class in Medi-Cal, and the costs of polypharmacy can be twice as much as the costs of monotherapy at therapeutic dosages. In this analysis of prescription data from Medi-Cal, the mean cost per patient for the polypharmacy group was more than three times that for the monotherapy group. If antipsychotic polypharmacy were more effective than monotherapy, this practice may actually reduce total costs despite the higher pharmacy costs. However, there are currently no data available to support the effectiveness of antipsychotic poly-pharmacy (2,3). Thus there is currently no reason to believe that antipsychotic polypharmacy would reduce total costs.

Despite the high economic costs, there are some patients for whom antipsychotic polypharmacy may be appropriate, and thus this option should remain open to clinicians. However, it may be prudent to reserve antipsychotic polypharmacy for patients who have not responded to adequate trials of monotherapy with first-line second-generation antipsychotics and who either do not respond to or are unable to tolerate clozapine (4,8). The drug use review board of the Medi-Cal division of the California Department of Health Services recommends that at least two—if not all five—first-line second-generation antipsychotic monotherapies be attempted before other treatment options (9). Monotherapy with first-generation antipsychotics, clozapine monotherapy, or augmentation with divalproex are also recommended before antipsychotic polypharmacy. This proposal is consistent with the revised recommendations of the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP)—that is, at least two trials of first-line second-generation antipsychotic monotherapy as well as a trial of clozapine before combination treatment is used (10).

Conclusions

The increasingly high costs of second-generation antipsychotics have raised the threat that use of these valuable resources will be restricted, most likely by removing certain agents from the formulary solely on the basis of economic factors. Offsetting the high costs of second-generation antipsychotics by reducing particularly costly yet poorly researched uses, such as polypharmacy, may be one means of eliminating the threat of imposed formulary restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer Incorporated.

The authors are affiliated with the Neuroscience Education Institute, 5857 Owens Avenue, Suite 102, Carlsbad, California 92008 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and use of second-generation antipsychotics in a sample of California Medicaid enrollees

1. Kapur S, Remington G: Atypical antipsychotics: new directions and new challenges in the treatment of schizophrenia. Annual Review of Medicine 52:503–517,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Stahl SM, Grady MM: A critical review of atypical antipsychotic utilization: comparing monotherapy with polypharmacy and augmentation. Current Medicinal Chemistry 11:313–327,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Freudenreich O, Goff DC: Antipsychotic combination therapy in schizophrenia: a review of efficacy and risks of current combinations. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 106:323–330,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Josiassen RC, Joseph A, Kohegyi E, et al: Clozapine augmented with risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:130–136,2005Link, Google Scholar

5. Anil Yagcioglu AE, Kivircik Akdede BB, Turgut TI, et al: A double-blind controlled study of adjunctive treatment with risperidone in schizophrenic patients partially responsive to clozapine: efficacy and safety. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:63–72,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Jaffe AB, Levine J: Antipsychotic medication coprescribing in a large state hospital system. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 12:41–48,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Tapp A, Wood AE, Secrest L, et al: Combination antipsychotic therapy in clinical practice. Psychiatric Services 54:55–59,2003Link, Google Scholar

8. Munro J, Matthiasson P, Osborne S, et al: Amisulpride augmentation of clozapine: an open non-randomised study in patients with schizophrenia partially responsive to clozapine. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 110:292–298,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Stahl SM, Simon-Leack J, Walker V: Developing an education program to reduce costs of atypical antipsychotics in the California Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) without imposing formulary restrictions. Presented at the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Montreal, Canada, June 23-27, 2002Google Scholar

10. Miller AL, Hall CS, Buchanan RW, et al: The Texas medication algorithm project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia:2003 update. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:500-508,2004Google Scholar