Assessment of the Burden of Disease Among Inpatients in Specialized Units That Provide Psychotherapy

Abstract

The burden of disease of 1,651 inpatients in the Netherlands who had complex personality problems and personality disorders and who were treated in specialized units that provide psychotherapy was compared with the burden of disease of patients with other mental and physical conditions. Patients completed the EuroQol EQ-5D, a generic quality-of-life questionnaire. The mean EQ-5D index score was .54 (possible scores range from -.59 to 1.00, with higher scores indicating fewer problems). This score reflects a burden of disease comparable with the burden in severe illnesses, such as Parkinson's disease (.58) or rheumatic disease (.53). (Psychiatric Services 56:1153-1155, 2005)

The relation between burden of disease, necessity of treatment, and reimbursement is not unique to psychotherapy. A high burden of disease among patients is in general associated with a greater need for treatment and more willingness to allocate financial resources (1). For this reason, unambiguous evidence about the burden of disease of patients who are receiving psychotherapy is necessary to convince health policy makers that a substantial investment in psychotherapy is worthwhile. This kind of evidence about the burden of disease is obtained with generic quality-of-life questionnaires. These instruments can measure the burden of disease regardless of patients' diagnoses and can therefore compare the burden of disease for patients receiving inpatient psychotherapy with, for example, patients who have severe somatic illnesses or who require surgery.

In this study we used a generic quality-of-life questionnaire, the EuroQol EQ-5D, to determine the burden of disease among inpatients who were receiving psychotherapy in specialized inpatient units.

Methods

The sample consisted of patients who were consecutively admitted to the inpatient psychotherapeutic treatment programs of 19 mental health care institutes throughout the Netherlands on or after January 1, 2001, and who were discharged before March 10, 2005. The institutes have specialized units that offer inpatient psychotherapy as the primary treatment approach. The units are located at regional psychiatric hospitals and centers for mental health care and at national centers of inpatient psychotherapy for patients with personality disorders.

In general, patients are referred because of complex personality problems and personality disorders that appear to be refractory to outpatient treatments. The specialized treatments are provided in a reconstructive psychotherapeutic milieu and consist of group psychotherapy; nonverbal therapies, such as creative therapy and movement therapy; and sociotherapy—that is, group discussions on living conditions in the hospital and at home. The length of inpatient stay is from three to 12 months. In most cases, aftercare is provided, but the frequency and intensity of aftercare programs vary widely. Treatments provided on the inpatient units are fully covered by the national health insurance system.

Patients were asked to complete a battery of self-report questionnaires as part of the Standard Evaluation Project (STEP), which is a system of quality monitoring initiated by the Dutch Foundation of Clinical Psychotherapy. The STEP questionnaires are routinely distributed to all patients at the start of psychotherapy. Informed consent from all patients and institutional review board approval were obtained. Patients with at least two inpatient days of treatment were considered to be inpatients.

The burden of disease was measured by using the EuroQol EQ-5D (2). The descriptive system of the EQ-5D records quality of life in five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities (such as work, study, housework, and family or leisure activities), pain or discomfort, and anxiety-depression. Each dimension is divided into three response levels: no problems, some or moderate problems, and extreme problems or inability to perform the activity. The responses on the five dimensions are weighted to arrive at a single index score between -.59 (worst imaginable health state) and 1.00 (best imaginable health state).

The patients' mean score on the nongeneric Symptom Checklist 90 Revised (SCL-90-R) is also presented so that the generic EQ-5D index score can be related to the more familiar indicator used in the mental health field. The SCL-90-R is a 90-item questionnaire that measures the degree of psychopathology. The outcomes of the SCL-90-R can be summarized in a single global distress index, the Global Severity Index (GSI). Possible GSI scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating a higher level of psychological and emotional distress.

The mean EQ-5D index score of inpatients receiving psychotherapy was compared with the mean EQ-5D index scores of patients with a variety of somatic illnesses. Well-known illnesses were chosen to serve as benchmarks. To examine the sensitivity of the EQ-5D to the burden of disease of these inpatients, we determined the correlation between the EQ-5D index score and the GSI score.

Results

The sample consisted of 1,651 patients who were consecutively admitted to the specialized inpatient psychotherapy units. A total of 541 patients (33 percent) were male, and the mean age was 31.9±9.2 years (range, 18 to 61 years).

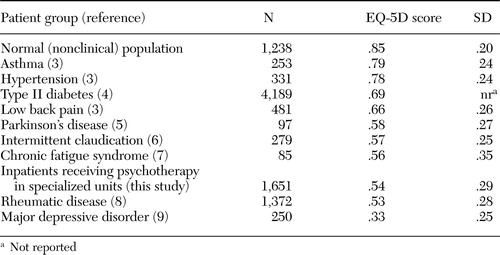

Table 1 lists the mean EQ-5D index scores for patients with a variety of conditions (3,4,5,6,7,8,9). The scores indicate that the burden of disease for patients on the inpatient psychotherapy units (.54) was comparable to the burden for patients with rheumatic disease (.53) or Parkinson's disease (.58). The burden of disease for the psychotherapy patients exceeded the burden for patients with diabetes and asthma.

The high burden of disease was mainly the result of problems reported in three of the EQ-5D's five dimensions. For usual activities, 1,118 patients (68 percent) reported some problems, and 195 (12 percent) reported extreme problems. For anxiety-depression, 961 (58 percent) reported some problems and 509 (31 percent) reported extreme problems. For pain-discomfort, 960 (58 percent) reported some problems, and 130 (8 percent) reported extreme problems.

The GSI score from the SCL-90-R supported the finding of a low mean EQ-5D index score. The mean GSI score for persons in the general population (that is, a nonclinical sample) is 1.3±.4 (10); patients on the inpatient psychotherapy units scored "very high" on the SCL-90-R (2.4±.6). The correlation between the GSI score and the EQ-SD index score was -.49 (Pearson's r).

Discussion

This study is the first to formally investigate the burden of disease in a large population of inpatients receiving psychotherapy in specialized units. Results show that these patients experienced a high burden of disease, which was comparable to the burden of disease of patients with severe somatic illnesses such as Parkinson's disease or rheumatic disease. The sensitivity of the EQ-5D in measuring the burden of disease in this population was good; the EQ-5D was correlated at a satisfactory level with the score on the nongeneric symptom checklist SCL-90-R.

Until more is known about the effectiveness of psychotherapy for this group of inpatients, it will continue to be difficult to advocate for policies that support reimbursement for psychotherapy for them. However, the study showed that these patients are highly impaired and in need of intensive treatments.

The burden of disease measured in this study is that of inpatients on specialized units that focus on establishing structural change among patients with severe personality problems and disorders that appear to be refractory to outpatient treatments. It is important to note that we cannot generalize our results beyond this select group of patients. Objections to funding psychotherapy for outpatients or for other groups of inpatients may still be raised.

The data in the STEP investigation is routinely collected, which makes it possible to collect a large amount of data but difficult to control for specific sample characteristics. For instance, some of the 19 participating centers experienced difficulty recruiting patients for the study in a routine way, which caused uncontrolled dropout. Furthermore, patients who explicitly refused to participate in the study were not identified, and they could not be compared with participants. However, we do not believe that these flaws in data collection had a significant influence on the main conclusions of this investigation. It is our impression that the number of explicit refusals was low, around 5 to 10 percent. Furthermore, the centers that had difficulty recruiting patients in a routine way were also the centers that did not contribute many patients to the sample, which limits their influence on the results. Nevertheless, future research with a strict inclusion protocol could provide additional support for our conclusions.

Our research also shows the importance of introducing generic quality-of-life instruments into the field of psychotherapy research. Use of outcome measures that have a meaning outside the professional field of psychotherapy will help convince the outside world that psychotherapy is worth the money. Simply showing that psychotherapy is effective in producing certain psychodynamic outcomes is not enough. Convincing arguments can be developed only if valid instruments are introduced that measure cost and effects in terms that are relevant and comprehensible for society, as in health economic evaluations and outcome research.

Acknowledgment

The research was partly funded by the Dutch Foundation of Clinical Psychotherapy.

Ms. Soeteman, Dr. Verheul, and Dr. Busschbach are affiliated with the Viersprong Institute for Studies on Personality Disorders, P.O. Box 7, 4660 AA Halsteren, Netherlands (e-mail, [email protected]). All the authors except for Dr. Verheul are with the department of medical psychology and psychotherapy of Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam. Dr. Trijsburg and Dr. Verheul are with the department of clinical psychology at the University of Amsterdam.

|

Table 1. EuroQol EQ-5D index scores of patients who were receiving psychotherapy in specialized inpatient units and of patients with other serious mental and physical conditions

1. Stolk EA, Brouwer WBF, Busschbach JJV: Rationalizing rationing: economic and other considerations in the debate about funding of Viagra. Health Policy 59:53–63,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Brooks R, Rabin R, de Charro F (eds): The Measurement and Valuation of Health Status Using EQ-5D: A European Perspective. London, Kluwer Academic, 2003Google Scholar

3. Burström K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F: Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Quality of Life Research 10:621–635,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Koopmanschap M: Coping with type II diabetes: the patient's perspective. Diabetologia 45:S18-S22, 2002Google Scholar

5. Siderowf A, Ravina B, Glick HA: Preference-based quality-of-life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurology 59:103–108,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bosch JL, Myriam Hunink MG: Comparison of the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3) and the EuroQol EQ-5D in patients treated for intermittent claudication. Quality of Life Research 9:591–601,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Myers C, Wilks D: Comparison of EuroQol EQ-5D and SF-36 in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Quality of Life Research 8:9–16,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wolfe F, Hawley DJ: Measurement of the quality of life in rheumatic disorders using the EuroQol. British Journal of Rheumatology 36:786–793,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Sapin C, Fantino B, Nowicki ML, et al: Usefulness of EQ-5D in assessing health status in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2:20–28,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Arrindell WA, Ettema JHM: Symptom Checklist: Handleiding bij een Multidimensionele Psychopathologie-Indicator [Symptom Checklist: Manual for a Multidimensional Indicator of Psychopathology]. Lisse, Netherlands, Swets and Zeitlinger, 2003Google Scholar