Mental Health Needs of Cohabiting Partners of Vietnam Veterans With Combat-Related PTSD

Abstract

The objectives of this study were to perform an initial needs assessment of partners of Vietnam veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and to assess the partners' current rates of treatment use. A telephone survey was conducted with 89 cohabitating female partners of male combat veterans who were receiving outpatient PTSD treatment at two Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. Although large majorities of partners rated individual therapy and family therapy to help cope with PTSD in the family as highly important, only about one-quarter of the partners had received any mental health care in the previous six months. The most commonly requested service was a women-only group.

Examining the mental health needs of partners of individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is important because of the marked difficulties PTSD patients have in close relationships, the clear effects of PTSD on families, and the literature for other serious mental illnesses that documents the efficacy of family intervention in reducing relapse. Although families of persons with serious mental illness have received considerable attention, the needs of partners of patients with PTSD have been relatively ignored.

The relationships of veterans who have PTSD are often marked by considerable instability and distress (1). These difficulties are likely created and sustained by the veteran's emotional numbing, increased proclivity toward domestic violence (2), and difficulties in emotional regulation.

Living with a person who has PTSD is often stressful, and these partners often express feelings of worthlessness and hurt when they present clinically. In addition, partners of veterans with PTSD report greater fears of intimacy (1), lower satisfaction with relationships (2), and poorer psychological adjustment (3) than partners of veterans without PTSD. These unhappy family members are often reluctant to provide support, and research has found an association between a partner's increased social withdrawal and increased intensity of the patient's PTSD symptoms (4). Some partners become critical and hurtful, thereby increasing tension in the relationship. This stressful family environment can then adversely affect PTSD treatment (5).

As noted above, supporting families of patients with serious mental illness produces clear benefits. The literature on schizophrenia demonstrates the efficacy of family psychoeducation in reducing relapse and enhancing family functioning (6). Clinically it is clear that including families in the treatment of PTSD assists with assessment, treatment planning, and improving patient and family satisfaction. Although family and marital treatments are available as adjunctive treatments for PTSD, efficacy data for PTSD are less well developed than for other serious mental illnesses (7). The only randomized clinical trial to apply behavioral family therapy to PTSD did not indicate any further reduction in symptoms beyond that gained by previous exposure therapy (8). Because there is no convincing evidence that supports the efficacy of family intervention for combat-related PTSD, performing a detailed analysis of family needs is important.

Research among families of patients with serious mental illness has shown that these caregivers want information about mental illness as well as help in advocating for their patient's needs (9). When families of residents of state inpatient psychiatric units were asked how these needs could be met, 35 percent wanted an informal self-help support group, and 29 percent wanted a professionally led support group (10).

It is possible that veterans with PTSD could benefit from family interventions that are effective in treating other serious mental illnesses. However, given the unique challenges of PTSD, the needs may be different. Additional program implementation and rigorous evaluation are needed, but research has yet to determine whether family members even desire or need mental health services. In an effort to understand the preferences of veterans' partners, we used a tested method to survey 89 partners of Vietnam veterans.

Methods

The sample comprised 89 cohabiting female partners of 89 Vietnam combat veterans. Veterans were recruited through outpatient PTSD treatment programs at the New Orleans and Jackson Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Centers from July to November 2002. Inclusion criteria for veterans included a history of service in the Vietnam War, a chart diagnosis of PTSD, service-connected disability for PTSD, active participation in the PTSD program, and current cohabitation with a female partner. On the basis of these criteria, 100 eligible patient-partner dyads were identified, yielding 89 total completed interviews of patient-partner pairs (17 from Jackson and 72 from New Orleans). The project was approved by the institutional review board and research and development committees at both sites.

The mean age of the partners was 52.01±5.78 years (range, 39 to 76). Approximately half the partners were white (45 partners, or 51 percent), and the others were African American (37 partners, or 42 percent) or Hispanic or other (seven partners, or 8 percent). More than three-quarters of the partners (77, or 87 percent) had at least a high school education. Most of the couples (81, or 91 percent) were married.

All Vietnam combat veterans who were currently receiving treatment in outpatient PTSD programs at the two VA medical centers were targeted for recruitment. At both sites, a research assistant approached veterans in the PTSD clinic waiting room and provided a sign-up sheet. In New Orleans, veterans completed the sign-up sheet immediately, including contact information for their partners. A modified procedure was used in Jackson because of site-specific requirements of the institutional review board (veterans and partners jointly completed paperwork and mailed it back to the hospital).

On receipt of the paperwork, an interviewer (who has a master's degree in psychology) contacted the veterans and partners by telephone and conducted the separate individual interviews. The interviewer obtained verbal informed consent from both the veterans and the partners (both parties needed to agree to participate to be eligible). At the Jackson site, all 17 recruited dyads completed the interview (100 percent response rate). At the New Orleans site, 11 of the 83 recruited dyads failed to complete the interview, yielding 72 completed interviews (87 percent response rate). The 11 dyads that were not included in the final sample did not differ demographically from the 89 who completed the study.

A telephone survey, called Partner Experiences With PTSD, was created through extensive pretesting. The survey contains 93 items and gathers demographic and clinical information from the partner. Embedded within the survey are two standardized, psychometrically sound clinical scales: the Burden Inventory and the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18), which contains three global scales: anxiety, depression, and somatization.

Partners' treatment experiences were assessed with one item on the frequency of psychiatric treatment in the previous six months. Partners' treatment needs were examined with use of two 5-point scale items, ranging from 0, not important, to 4, extremely important, assessing the importance of being able to obtain "therapy sessions to help you cope with the stress of living with your partner" and "family therapy sessions." Patient-partner contact is the sum of seven items that assess how involved partners are in the patient's life. One 5-point scale item reflects overall emotional involvement, and six items reflect the frequency of specific behaviors—for example, giving a partner a ride—in the previous month.

Partners' appraisal of patient threat was calculated as the sum of three 5-point scale items assessing the perceived degree of threat the veteran's emotional difficulties pose to the relationship and the partner's well-being. Participants who reported feeling in danger were referred for immediate intervention.

Results

Fifty-seven partners (64 percent) reported that having access to individual therapy to help them cope more effectively is extremely or very important. Sixty-nine partners (78 percent) reported that it is extremely or very important for the veteran and the partner to be given family therapy.

Despite these stated desires, only 25 partners (28 percent) had received any mental health care in the previous six months. Furthermore, ten (40 percent) of these service recipients received minimal intervention (one or two times over the previous six months). Regarding the open-ended item soliciting the kinds of services that could help to "better support their loved ones," more than half the partners (45, or 54 percent) requested a women-only group, and 17 (20 percent) requested an educational program about PTSD. Other commonly desired services included individual treatment for the partner (16 partners, or 19 percent) and couples therapy (11 partners, or 13 percent). The three most commonly requested interventions involved only partners (not patients).

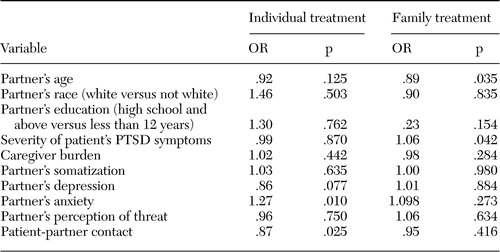

Two logistic regression models (Table 1) were used to identify variables associated with partners' rating of individual or family therapy as extremely important. Because about half the sample described both individual and family therapy as "extremely important," a median split approach was used to examine the partners in each category for both modes of treatment. The dependent variable in the first model was the partner's assessment of her need for individual treatment as extremely important (yes or no). The second model's dependent variable was the partner's appraisal of family treatment being extremely important (yes or no). The independent variables in both models were demographic and clinical variables (Table 1).

The significant predictors for desired individual treatment included partner's anxiety and patient-partner contact. The greater the partner's anxiety, the more likely it was that the partner would rate individual treatment as extremely important. Furthermore, the more contact partners had with the patients, the less likely partners were to rate their need for individual treatment as extremely important.

The significant predictors of strong desire for family treatment included the partner's age and the severity of the patient's PTSD symptoms. Older people were less likely to describe family treatment as extremely important, and partners whose patients had high levels of PTSD symptoms were more likely to strongly desire family treatment.

Discussion

Partners of veterans with PTSD expressed a strong desire for both family therapy and individual treatment. Despite this clear call for services, only 28 percent had received any mental health care in the previous six months. Other analyses based on this data set indicated that the partners' mean score on all three BSI-18 subscales surpassed the 90th percentile (unpublished data, Manguno-Mire GM, 2004). These partners were highly distressed, and most desired services. However, very few had received treatment, likely because of barriers such as scheduling, transportation, and stigma. Regression analyses showed different predictors of desiring individual rather than family treatment. Future research should investigate these differences further.

Several factors limit the generalizability of these findings. All the veterans were Vietnam combat veterans, were cohabiting with a female partner, received VA disability for PTSD, and had a telephone. Furthermore, we used convenience sampling, wherein all veterans were active in treatment. Thus the ability to extrapolate these findings to other veterans is uncertain. Future research should involve a controlled study of partners' involvement to examine the effects on the patient.

Conclusions

Partners of veterans with combat-related PTSD constitute a distressed group that is uninvolved in treatment. The telephone survey used in this study showed a large gap between the perceived needs of these partners and the services that are provided. This preliminary needs assessment can guide the development and testing of new interventions to determine whether and how family services might improve outcomes for veterans and their partners. Treatments need to be tailored to each couple's specific needs and may differ for veterans from different theaters of war.

Dr. Sherman is director of the family mental health program of the Oklahoma City Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, 921 N.E. 13th Street, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Sautter is with the family mental health program of the New Orleans VA Medical Center. Dr. Lyons is with the department of mental health at the G. V. (Sonny) Montgomery Jackson VA Medical Center. Dr. Manguno-Mire is with the department of psychiatry and neurology of Tulane University in New Orleans. Ms. Han, Ms. Perry, and Dr. Sullivan are with the department of psychiatry of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. All authors are also affiliated with the South Central Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC).

|

Table 1. Logistic regression models of the need for individual and family treatment among partners of Vietnam veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

1. Riggs DS, Byrne A, Weathers FW, et al: The quality of the intimate relationships of male Vietnam veterans: problems associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 11:87–101,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Fairbank JA, et al: Problems in families of male Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:916–926,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Calhoun PS, Beckham JC, Bosworth HB: Caregiver burden and psychological distress in partners of veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 15:205–212,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Solomon Z, Mikulincer M, Avitzuer E: Coping, locus of control, social support, and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55:270–285,1988Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Tarrier N, Sommerfield C, Pilgrim H: Relatives' expressed emotion (EE) and PTSD treatment outcome. Psychological Medicine 29:801–811,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Falloon IRH, Roncone R, Held T, et al: An international overview of family interventions: developing effective treatment strategies and measuring their benefits for patients, carers, and communities, in Family Interventions in Mental Illness: International Perspectives. Edited by Lefley HP, Johnson DL. Westport, Conn, Praeger, 2002Google Scholar

7. Riggs DS: Marital and family therapy, in Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines From the International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies. Edited by Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman, MJ. New York, Guilford, 2000Google Scholar

8. Glynn SM, Eth S, Randolph ET, et al: A test of behavioral family therapy to augment exposure for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67:243–251,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Gasque-Carter KO, Curlee MB: The educational needs of families of mentally ill adults: the South Carolina experience. Psychiatric Services 50:520–524,1999Link, Google Scholar

10. Glynn SM, Pugh R, Rose G: Predictors of relatives' attendance at a state hospital workshop on schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:67–70,1990Abstract, Google Scholar