Effect of Structured Interviews on Evaluation Time in Pediatric Community Mental Health Settings

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to determine whether a structured interview administered by a master's-level clinician and reported to physicians before an initial evaluation would reduce physicians' evaluation time without compromising diagnostic accuracy or clinical outcomes in a pediatric sample. METHODS: A sample of 225 children and adolescents who were seen in public-sector community facilities was randomly assigned either to receive a structured interview (the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children-Present and Lifetime Versions) by a trained interviewer before the initial physician visit or to receive assessment as usual. Clinical outcome data were collected prospectively, with follow-up at four months. RESULTS: Physicians' evaluation time was reduced by approximately half among physicians who were given preliminary diagnostic information. Physicians' diagnoses were strongly related to the results of the structured interview. Physicians' having access to previously obtained diagnostic information was associated with better psychosocial functioning at follow-up in terms of peer relations and spare-time activities compared with assessment as usual. CONCLUSIONS: Adding a trained diagnostic interviewer to the clinical team could reduce physicians' initial diagnostic evaluation time and improve diagnostic reliability and psychosocial outcomes.

In medicine, the need to establish an efficient, accurate diagnosis is especially important for the mental health professions (1,2,3). Diagnosis in public-sector settings and other clinical settings tends to be abbreviated and cursory, without time to explore in detail all diagnostic possibilities. It is not surprising to find large discrepancies between community practitioners' abbreviated diagnoses and those based on structured diagnostic interviews administered by highly trained staff in academic research settings (4,5,6). An efficient, accurate, and reliable diagnosis that leads to prompt, correct treatment plays a key role in keeping costs down by requiring less of physicians' time while improving effectiveness and patient satisfaction with service. The challenge is to improve diagnostic reliability and efficiency while reducing the cost of the diagnostic process in terms of physicians time (7,8).

Previous studies have identified poor reliability between the results of a standard administered structured diagnostic interview and the diagnosis obtained by clinic staff in the course of routine diagnostic assessments of children and adolescents in the public sector (9). Similar findings have been published for adults (6). A recent study conducted in an adult community mental health center showed that providing structured diagnostic information to physicians before their evaluations of adult psychiatric patients was associated with increases in the frequency of evaluation and diagnostic visits, changes in diagnoses, and changes in medications consistent with the updated diagnosis (5). In addition, the new diagnosis tended to match the structured diagnosis. The authors of the study found that attending psychiatrists were three times as likely to include additional evaluation procedures and ten times as likely to make a clinically significant change in diagnosis and a change in prescription consistent with the newer diagnosis compared with control physicians conducting routine evaluations without the independently administered structured interview.

The study reported here was conducted to determine whether the inclusion of a structured diagnostic interview with a trained master's-level rater and additional supplementary assessment data for children and adolescents treated in the public sector would improve overall diagnostic reliability compared with routine assessment and treatment as usual (10,11) and reduce physicians' evaluation time rather than add to it. We also aimed to determine whether improved diagnoses would affect physicians' prescribing practices (changes in medications or dosages) and traditional treatment outcome measures. The findings for two groups of patients who were randomly assigned to receive the extended evaluation or to be assessed and treated as usual were compared.

Methods

Study participants

The patients were 225 consecutive child and adolescent patients who were seen as outpatients at the Tarrant County Mental Health and Mental Retardation community centers in Fort Worth, Texas, from January 24, 2002, to May 1, 2003. The patients either were receiving their first medication evaluation or had not been seen for such an evaluation within the previous year. The patients consented to an additional evaluation before the visit with the psychiatrist and an additional follow-up evaluation four months later. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and Tarrant County Mental Health and Mental Retardation community centers.

Patients were excluded from the database if they did not have any DSM-IV axis I diagnosis listed in their medical record or if the diagnosis had been deferred. They were paid a nominal fee for their participation ($20 for the parent and $15 for the child).

Design

The patients were randomly assigned to receive either an extended evaluation before evaluation by the physician or routine assessment as usual (control group). The SAS statistical program was used to generate a random-number list for two groups to assign patients to a condition sequentially as they consented to participate. The extended-evaluation group received a structured diagnostic interview designed for children and adolescents (the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children—Present and Lifetime Versions [KSADS-PL]) (12) administered by trained master's-level research clinicians to the parent and separately to the child, along with the clinician-administered Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale for Children (13,14).

The research coordinator then met briefly with the psychiatrist to present the results of the assessment before the psychiatrist's initial meeting with the patient and his or her family. Treatment was determined by the physician. All physicians saw an equal number of assessment-as-usual and extended-evaluation patients over time. The physicians were two child psychiatrists, assisted by one physician assistant who was supervised by the psychiatrists. A four-month follow-up evaluation by the research clinician was scheduled at a time that typically corresponded with a scheduled physician visit with the patient. Of the 225 patients who were seen at baseline, 195 (87 percent) returned for a follow-up visit four months later.

The parent completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (15) for both assessments as usual and extended evaluations. Similarly, the Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA) (16) was used to gather general information about functioning from both groups. In addition to the clinic's routine CBCL that was administered to every patient, the assessment-as-usual group was administered the BPRS-C9 and the SAICA for clinical research outcome data. However, that information was not presented to the physician, because it was not a part of these sites' routine assessments.

Measures

The KSADS-PL. The KSADS-PL is a semistructured interview designed to ascertain present-episode and lifetime history of psychiatric illness on the basis of DSM-IV criteria. Interrater and test-retest reliability have been established, as have convergent and discriminate validity (12).

The BPRS-C9. The nine-item anchored version of the BPRS-C9 for children is a subset of the recently anchored version of the original 21-item version (13). It is a clinician-scored instrument designed to characterize individual patients in terms of symptoms of childhood psychiatric disorders and to evaluate response to treatment. This nine-item interview can usually be completed in half the 20- to 30-minute period required for the 21-item version.

The CBCL. The CBCL is a questionnaire designed for parents to provide a standardized description of a child's social competencies and problem behaviors (15). Most parents who have at least fifth-grade reading skills can complete the instrument; otherwise, the items are read to them.

The SAICA. The SAICA is a semistructured interview that was designed for administration to school-aged children and to parents in reference to their children, for use in clinical and epidemiologic studies. Four areas of role performance are covered: school, spare-time activities, peer relations, and home functioning. The instrument has good demonstrated reliability and validity and has been widely used in diverse U.S. samples (17,18).

Statistical analyses

The data were computerized and managed with use of an SPSS spreadsheet. SPSS was also used for the analyses. Independent double entry and SAS PROC COMPARE were used to ensure data integrity. Data are reported as means and standard deviations or frequencies and effect sizes where appropriate (19). For discrete variables, group differences were tested with a two-tailed Yates continuity-corrected chi square. For continuous variables, two group differences were tested with two-tailed independent t tests. Comparisons for the continuous measures between groups and their baseline and follow-up scores were based on repeated-measures analysis of variance as described below.

Results

Participation

A total of 724 individuals were scheduled for new patient evaluations. Of the 506 patients who kept their appointments (70 percent), 225 (44 percent) participated in the study and 281 (56 percent) did not. Reasons for not participating included refusal or time limitations (118 patients, or 42 percent), not having a legal guardian available (eight patients, or 3 percent), not speaking English (14 patients, or 5 percent), not being between the ages of five and 17 years (11 patients or 4 percent), not being available for previsit scheduling (39 patients, or 14 percent), participating in another study (62 patients, or 22 percent), or research staff's not being able to meet with patients because of schedule conflicts (28 patients, or 10 percent).

The ethnic representation was mixed (less than half Caucasian), and the sample was characterized by the lower socioeconomic status that is typical of public-sector community mental health settings. Of 225 patients, 107 (48 percent) were Caucasian, 44 (20 percent) were Hispanic, 60 (27 percent) were African American, and 14 (6 percent) were of a unique other race or mixed race. No differences were found between the assessment-as-usual group and the extended-evaluation group in terms of age (11.5±3.6 compared with 11.5±3.6 years), gender (38 female and 73 male compared with 46 female and 68 male), school grade (5.3±3.4 and 5.2±3.3), or socioeconomic status (20) (3.8±.7 and 3.7±.8, where 1 represents the highest status, 3 the middle, and 5 the lowest, based on both years of education and occupation) or any other demographic variables.

Physicians' and research clinicians' time

An initial question was whether having the research clinician would reduce the time required for the physician to complete an initial evaluation. The amount of time required for an initial diagnostic evaluation was cut in half when physicians were given diagnostic and history information in advance as opposed to not being given that information (31.2±9.4 compared with 60.7±20.2 minutes; F=129, df=1, 146, p<.001) (N=75 for the control group and N=73 for the extended-evaluation group), with a very large effect size (eta2=.47) (19). On average, the clinical evaluator spent 108.7±16.4 minutes (median, 110 minutes; range, 30 to 150 minutes).

Diagnostic characteristics

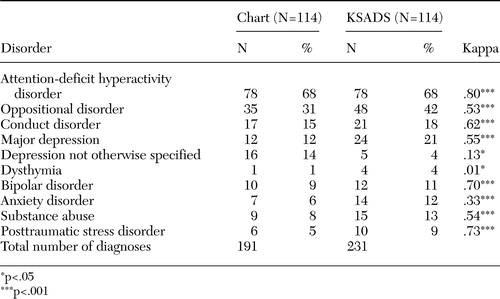

The KSADS-PL identified more diagnoses per individual than did physicians' initial chart diagnoses, even when the KSADS diagnoses were provided to physicians in advance of the evaluation (231 compared with 191) (Table 1). Physicians who were given the KSADS results in advance ended up with more initial chart diagnoses than those who were not given that information (191 compared with 165 diagnoses), which suggests that the additional diagnostic assessment information had increased the number of diagnoses included in the chart and perhaps influenced the diagnostic process as well. The only significant differences found between the KSAD diagnosis and the physician's initial diagnosis in chi square analyses was for conduct disorder. The physicians who were given the KSADS data in advance of their initial evaluation reported twice as many patients with conduct disorder, consistent with the KSADS diagnosis, as did the assessment-as-usual physicians (χ2=4.4, df=1, p<.04).

The biggest discrepancies were for the diagnosis of the depressive disorders, with twice as many diagnoses of major depression (21 percent) by the KSADS compared with physician assessment (12 percent and 7 percent, respectively). Physicians tended to use the diagnosis of depression not otherwise specified (14 percent) instead of major depression, whereas the KSADS identified only 4 percent of patients as having depression not otherwise specified. Similarly, there was little use of diagnosis of dysthymia by physicians (2 percent). Ultimately, all the depressed patients were treated for depression, but their chart diagnoses differed. Otherwise, the percentage of patients who were given any particular diagnosis was reasonably consistent between the two groups (Table 1).

Reliability measures were calculated for comparison of initial chart diagnoses for physicians who had also received the results of the KSADS in advance of their evaluation and the KSADS diagnoses (Table 2). For all comparisons, the best reliability as estimated by the kappa statistic was found for the diagnoses of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, followed by bipolar disorder and conduct disorder. Diagnoses of major depression, substance abuse, and oppositional disorders had moderate kappas. No significant reliability was found for depression not otherwise specified or dysthymia, and the kappa value was low for anxiety disorder.

The high reliability for bipolar disorder between the initial chart diagnosis of the extended-evaluation group and the assessment-as-usual group was surprising given our previous findings for this disorder (14) and the difficulty in making this particular diagnosis accurately. Only in recent years has this disorder been recognized among children and adolescents, as opposed to the other disorders. By contrast, diagnoses of depression and dysthymia continued to have poor reliability, which may reflect the diagnostic dilemma that these disorders present in terms of duration and determination of numbers of symptoms or reluctance to use the major depression diagnosis.

Clinical medication and treatment outcomes

Having the additional diagnostic information was associated with more switches to a different medication for the extended-evaluation group (96 of 144, or 84 percent) than the assessment-as-usual group (73 of 111, or 66 percent) (χ2=11.6, df=3, p=.009). The extended-evaluation group also had twice as many dosage changes compared with the assessment-as-usual group (23 of 114, or 20 percent, compared with nine of 11, or 8 percent) (χ2=4.4, df=1, p<.04). Both these findings are indirect evidence that the extended evaluation provided additional diagnostic information that may have influenced physicians' change in current status of medication treatment compared with assessment as usual, which replicates earlier work (5).

The additional diagnostic information did not appear to be significantly associated with any of the other physician-based outcomes, with no differences between the extended-evaluation group and the assessment-as-usual groups related to medications or visits—for example, side effects, augmentations of medications, discontinued medications, or number of clinic visits.

Clinical measures

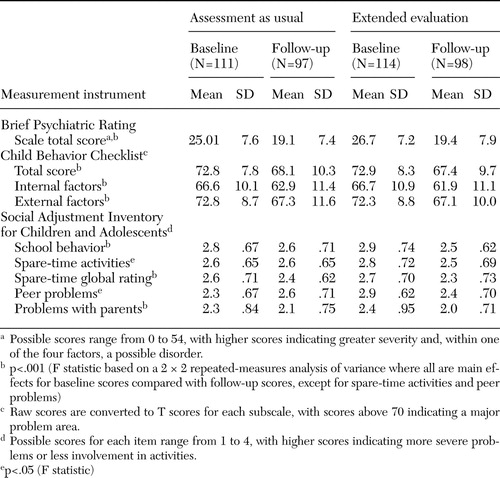

A final question addressed in this study was whether reduction in physicians' diagnostic evaluation time would have a negative impact on traditional measures of clinical outcome. The statistical analysis was a 2 × 2 repeated-measures analysis of variance that resulted in an F statistic for group, one for the repeated-measures baseline compared with the follow-up evaluation, and one for the interaction of the two. We also included a term for gender that was not significant in any of the analyses and hence restricted the report of findings to the 2 × 2 without gender. The clinician-rated BPRS-C9 total scores, a rating of overall psychiatric functioning, indicated significant improvement for both groups but without differential outcomes for extended evaluation or assessment as usual. The CBCL total score and both the internal and external subscores revealed significant improvements over time for both the extended-evaluation group and the assessment-as-usual group, without between-group differences. No significant interactions were found between baseline or follow-up measures and group for the above measures, indicating that both groups showed improvement at approximately the same rates.

In terms of overall functioning (SAICA scores), a number of different domains were assessed (Table 2). Problems related to overall spare-time activities did not change over time for the assessment-as-usual group but did show a significant improvement with treatment for the extended-evaluation group based on a main effect for group (F=6.6, df=1, 192, p<.01). Similarly, functioning related to problems with peers improved significantly for the extended-evaluation group according to the interaction (F=8.4, df=1, 191, p<.004) and may have slightly declined for the assessment-as-usual group. The functional measures of school behavior and problems with parents improved with time but did not differentiate between the assessment-as-usual group and the extended-evaluation group. No changes were noted in functioning between the groups for the other SAICA subscales, although it did show improvement over time.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that use of a master's-level trained structured diagnostic interviewer significantly reduced the time required for a physician to conduct an initial diagnostic evaluation in a public-sector setting. The amount of time required for the initial diagnostic evaluation was typically cut in half, to approximately 30 minutes. This finding has a number of implications both for cost savings and for staffing patterns for such facilities. The suggestion is that in essence the addition of a research diagnostic clinician at one-fifth to one-third of the salary of a staff physician would allow for the doubling of the number of patients seen by the physician. The result either could be a savings (half the physician time required) or, in a fee-for-service operation, could double the amount of revenue generated by doubling the number of physician evaluations conducted. Alternatively, recent concern for budgetary constraints limiting the amount of time psychiatrists can spend may compromise quality of care, which in turn may be addressed by implementing a position for a research clinician who can provide more detailed diagnostic and assessment information very economically to supplement and guide the physician—a master's-level diagnostic clinician's time is much less costly than that of a physician.

The approach used in this study was to provide the structured diagnostic interview data directly to the physician before the evaluation of the patient to determine whether, in addition to saving the physician time, this information had an effect on clinical diagnosis. In earlier studies, such an assessment was an adjunct to the standard practice following the initial diagnosis; it did not appear to influence changes in existing chart diagnoses and suggested poor reliability on many diagnoses (9). Other studies have also shown that inaccurate diagnoses are common in community clinics (21,22), and some have demonstrated that the uses of structured diagnostic interviews improve diagnostic accuracy (5,6,9). Our study demonstrated significantly improved kappas compared with a previous study (9). In addition to the improved kappas for diagnostic reliability in this study, we also found that more DSM-IV axis I diagnoses were recorded in the chart initially, as well as a greater frequency of the use of the major depression, conduct disorder, and anxiety disorder diagnoses, presumably as a result of the additional confirmatory symptom information.

Previous studies (9,23) showed poor diagnostic reliability for the specific mood disorders of major depressive disorder, depression not otherwise specified, and dysthymia. This diagnostic discrepancy was apparent for the study reported here as well, despite the fact that structured diagnostic information was provided to the physician in advance. This finding most likely reflects a very common practice of many public-sector psychiatrists to typically use depression not otherwise specified to cover most bases rather than strictly adhering to DSM-IV major depression criteria. Nonetheless, the more global overall inclusive mood disorder category (excluding the bipolar disorders) is reliable, and the selected treatment for the depressive disorder remains the same (4,23) whether this is a recent depressive episode or one that has had a longer prodromal course of more than 12 months, suggesting dysthymia or double depression. Finally, fewer symptoms are required for a diagnosis of depression not otherwise specified than for major depression, and once the determination that depression is present is made, delimiting all the symptoms may be seen as more of an academic exercise than a clinical one.

We initially raised the question of whether reducing physicians' initial diagnostic time would adversely affect treatment outcomes. It was an important finding that for all clinical outcome measures related to medications and clinical behavior and functioning measures, there were no negative effects of reducing physicians' initial assessment time. The extended-evaluation group did have more changes in dosages and medications, which may reflect the result of better diagnoses. The findings for the CBCL, a traditional measure of childhood behavior, indicated significant improvement. However, the extended-evaluation and assessment-as-usual groups did not differ from each other in the rate of improvement. Interestingly, on the measures of functioning (the SAICA), the patients who had the extended evaluation showed more improvement on problems related to spare-time activities and problems related to peers. It is possible that this finding is due to receipt of a more appropriate medication and identification of problem solving as part of the overall treatment strategy.

This demonstration of improved efficiency in the initial diagnostic process, coupled with an absence of adverse findings on treatment outcomes as a result of the reduced time, is an important result. The next logical step is to combine such a diagnostic process with the implementation of medication guidelines (4,23,24,25,26,27). Two recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of implementing such algorithms in pediatric public-sector settings (23,26). Other recent work demonstrates the benefits of concomitant psychoeducational material (28). Clearly there is a need for a study that combines use of the structured diagnosis before the evaluation along with medication guidelines and psychoeducation, all as a part of the same study to test for efficient use of physicians' time and improved clinical services outcomes that result in reduced total treatment needs and recidivism.

The study was limited by the fact that we followed patients for only four months, used only two public-sector clinics staffed by two child psychiatrists and a physician assistant, and did not use additional measures that could have helped to get better estimates of cost savings to reflect the reduced physician evaluation time that was found. Additional measures could have quantified the findings of improved patient and family satisfaction with the extended evaluations and additional attention from the follow-up visit (23). Likewise, measures that captured the study participants' higher retention rate and greater likelihood of making a follow-up visit would help to demonstrate the positive effects from the addition of master's-level clinical evaluators.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that a master's-level clinician can be trained to provide accurate structured diagnostic information to a child psychiatrist before the psychiatrist sees a patient and his or her family, which can reduce the time required for the physician to conduct the initial evaluation. The structured diagnostic information can improve reliability for the initial chart diagnosis, which, it has been argued, leads to improved treatment and outcome. The physicians who received the additional diagnostic information in this study made more changes in medications and dosages, a finding that replicates a previous study among adult patients (5). The clinical outcome measures for the extended-evaluation group showed improved psychosocial functioning with peers and spare-time activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristi Lewis, R.N. Kathi Rishel, M.D., and Shashi Motgi, M.D. The study was supported in part by Mental Health Connections, a partnership between the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation and the department of psychiatry of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The study was funded by the Texas State Legislature and by grants MH-4115 (to AJR) and MH-39188 (to GJE) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5232 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, Texas 75390 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Comparison of physicians initial chart diagnoses and present-episode diagnoses based on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children (KSADS)

|

Table 2. Comparison of baseline and follow-up functioning among children who received treatment and assessment as usual and those who received an extended evaluation

1. Jensen PS, Roper M, Fisher P, et al: Test-retest reliability of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC 2.1). Archives of General Psychiatry 52:61–71,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lahey BB, Flagg EW, Bird H: The NIMH Methods for the Epidemiology of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders (MECA) Study: background and methodology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:855–864,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Shaffer D, Schwab-Stone ME, Fisher P, et al: The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Revised Version (DISC-R): I. preparation, field testing, interrater reliability, and acceptability. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:643–650,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hughes CW, Emslie GJ, Crismon ML, et al: The Texas Children's Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1442–1454,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kashner TM, Rush AJ, Suris A, et al: Impact of structured clinical interviews on physicians' practices in community mental health settings. Psychiatric Services 54:712–718,2003Link, Google Scholar

6. Basco MR, Bostic JQ, Davies D: Methods to improve diagnostic accuracy in a community mental health setting. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1599–1605,2000Link, Google Scholar

7. Hoagwood K, Jenson PS, Petti TA: Outcomes of mental health care for children and adolescents: I. a comprehensive conceptual model. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1055–1063,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Jensen JB, Hoagwood K, Petti TA: Outcomes of Mental Health Care for Children and Adolescents: II. literature review and application of a comprehensive model. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1064–1077,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hughes CW, Rintelmann J, Mayes TL, et al: Structured interview and uniform assessment improves diagnostic reliability. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 10:119–131,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Verhulst FC, Van der Ende J, Ferdinand RF, et al: The prevalence of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a national sample of Dutch adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:329–336,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Aronen ET, Noam GG, Weinstein SR: Structured diagnostic interviews and clinicians' discharge diagnoses in hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:674–681,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, et al: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:980–988,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hughes CW, Rintelmann J, Emslie GJ, et al: A revised anchored version of the BPRS-C for childhood psychiatric disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 11:77–93,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Hughes CW, Stewart S, Emslie GJ, et al: A nine item anchored version of the BPRS-C. Presented at the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit (NCDEU) 44th Annual Meeting (abstract). Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 12:293–294,2002Google Scholar

15. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist / 4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, University of Vermont, 1991Google Scholar

16. John K, Gammon GD, Prusoff BA, et al: The Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents (SAICA): testing of a new semistructured interview. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 26:898–911,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Pawlby SJ, Mills A, Taylor A: Adolescent friendships mediating childhood adversity and adult outcome. Journal of Adolescence 20:633–644,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Sanford M, Boyle MH, Szatmari P, et al: Age-of-onset classification of conduct disorder: reliability and validity in a prospective cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:992–999,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1988Google Scholar

20. Hollingshead A: Four-factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, Conn, Yale University, 1975Google Scholar

21. Segal DL, Hersen M, Van Hasselt VB: Reliability of diagnosis in older psychiatric populations using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 15:347–356,1993Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Shear MK, Greeno C, Kang J: Diagnosis of nonpsychotic patients in community clinics. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:581–587,2000Link, Google Scholar

23. Emslie GJ, Hughes CW, Crismon ML, et al: A feasibility study of the childhood depression medication algorithm: the Texas Children's Medication Algorithm Project (CMAP). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43:1–9,2004Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Pliszka SR, Greenhill LL, Crismon ML, et al: The Texas Children's Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: I. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:908–919,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pliszka SR, Greenhill LL, Crismon ML, et al: The Texas Children's Medication Algorithm Project: report of The Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: II. tactics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:920–927,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Pliszka SR, Lopez M, Crismon ML, et al: A feasibility study of the Children's Medication Algorithm Project (CMAP) algorithm for the treatment of ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:279–287,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Rush AJ, Rago WV, Crismon ML, et al: Medication treatment for the severely and persistently mentally ill: the Texas Medication Algorithm Project. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:284–291,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Lopez MA, Toprac MG, Crismon ML, et al: A psychoeducational program for children with ADHD or depression and their families: results from the CMAP feasibility study. Community Mental Health Journal 41:51–66,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar