Pharmacotherapy and Health Care Costs Among Patients With Schizophrenia and Newly Diagnosed Diabetes

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study investigated how antipsychotic pharmacotherapy and health care costs change after diabetes mellitus is newly diagnosed among patients with schizophrenia. METHODS: Administrative data from the Department of Veterans Affairs were retrospectively reviewed to examine patients with schizophrenia who did not have any history of diabetes and for whom a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy was prescribed for any three-month period between June 1999 and September 2000. Data for these patients were reviewed through September 2001. Patients who were given a new diagnosis of diabetes were identified, along with a matched comparison group of patients who were not given a diagnosis of diabetes. Medication changes and costs were compared between patients with diabetes and those without and between patients who were taking second-generation antipsychotics and those who were taking first-generation antipsychotics. RESULTS: Of the 56,849 patients who fit the criteria for the study, 4,132 (7.3 percent) were subsequently given a diagnosis of diabetes (7.4 percent were taking second-generation antipsychotics and 7.1 percent were taking first-generation antipsychotics). Differences in the proportions of patients with and without diabetes who switched or discontinued antipsychotics were small and were statistically significant only for patients who were taking risperidone before the diabetes diagnosis date. The average marginal cost of treating a patient with diabetes was $3,104 over an average follow-up of 15.7 months, or $6.59 per day. Because the attributable risks of diabetes with second-generation antipsychotics averaged .875 percent, the average additional daily cost per patient that was attributable to each second-generation medication was small, ranging from $.003 for risperidone to $.134 for clozapine. CONCLUSIONS: Surprisingly, a new diagnosis of diabetes did not result in substantial antipsychotic medication changes, even among patients who were taking clozapine or olanzapine. Even though the costs of treating patients with newly diagnosed diabetes were substantial, the increased costs attributable to second-generation antipsychotics were small.

Second-generation antipsychotics—including clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole—have been found to be as effective in the treatment of schizophrenia as first-generation antipsychotics (1,2,3,4,5,6,7), with substantially fewer extrapyramidal side effects (8). However, some evidence suggests that these medications are associated with other side effects, such as weight gain and increased risk of diabetes mellitus (9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19).

A previous study examined the incidence of newly diagnosed diabetes among patients with schizophrenia who were stably medicated with an antipsychotic; the study showed increased risk specifically associated with clozapine and olanzapine and less risk associated with risperidone and first-generation antipsychotics (20). However, little is known about how clinicians respond to new-onset diabetes among patients with schizophrenia who are treated with a second-generation antipsychotic. Discontinuing the medication may help control the diabetes but may lead to the exacerbation of schizophrenia symptoms. Hence clinicians may be reluctant to change medications and may try to manage the diabetes in other ways. These choices have implications for the cost of care and the patients' well-being.

In an effort to better understand the consequences of new-onset diabetes among patients with schizophrenia who were taking antipsychotics, this study focused on the following questions: Do patients with schizophrenia who were initially given a prescription for a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy and later develop diabetes change their pharmacotherapy regimen after the diagnosis of diabetes? Are changes in antipsychotic pharmacotherapy after a new diagnosis of diabetes different depending on whether the patient was taking first- or second-generation antipsychotics? What are the costs associated with managing diabetes in this group of patients? What are the net costs per patient treated with each drug?

To address these questions we conducted an observational study in which patients with schizophrenia for whom a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy was prescribed and who had no history of diabetes were followed retrospectively by using administrative data from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Patients with a new diagnosis of diabetes were identified, along with a matched comparison group of patients who were not given a diagnosis of diabetes, and medication changes and costs were compared, by the patient's diabetes and medication status.

Methods

Sources of data

Data for the study came from VA national administrative databases. First, all VA outpatients were identified who were given a diagnosis of schizophrenia between October 1, 1998, and September 30, 2000 (fiscal years 1999 and 2000). Patients were identified as having schizophrenia if they had at least two outpatient encounters in a specialty mental health outpatient clinic with a primary or secondary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 codes 295.xx). Next, all prescription drug records were collected for these patients from June 1, 1999, to September 30, 2001.

For the cost component of the study, outpatient and inpatient service use was calculated by using the outpatient and inpatient care files. Unit costs for inpatient and outpatient services were calculated by using the cost distribution report. The cost distribution report is an accounting system that identifies total expenditures and unit costs associated with all VA inpatient and outpatient health care services. By using accounting procedures that were standardized across the entire VA, both direct and indirect costs were identified and distributed over each major type of health care service (21).

Sample

First, we identified patients for whom a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy was prescribed during any three-month period between June 1, 1999, and September 30, 2000. Patients were identified as having received a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy if they were given a prescription for the same agent during the three-month period, although the dosage could vary. We defined five groups of antipsychotic medications: clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and any first-generation antipsychotic. Ziprasidone and aripiprazole were not included in the study because they were only recently approved for use and because very few patients received these drugs during the study period.

Outpatient administrative records were checked to determine whether the patient had existing diabetes in the six months before the three-month prescribing period. Patients with any claims for diabetes (ICD-9 codes 250.xx, 357.2x, 362.0x, and 366.41) or with fewer than two medical primary care visits during that time were excluded from the sample. We required at least two primary care visits to ensure that patients with existing diabetes would be identified. Patients for whom a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy was prescribed and who had no history of diabetes were followed through September 30, 2001 (the end of fiscal year 2001). Patients who were given a diagnosis of diabetes during the follow-up period (which ranged from nine to 25 months after the three-month prescribing period) were identified, along with the date that diabetes was first diagnosed.

A matched comparison group of patients who were not given a diagnosis of diabetes during the follow-up period was also identified. Because a previous study showed that 25 percent of patients with schizophrenia who were initially given a prescription for a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy changed their antipsychotic medication during the following year (22), a comparison group was needed to determine whether observed medication changes that were associated with newly diagnosed diabetes were more frequent than they would otherwise have been. The comparison group was also needed to determine the incremental costs of treating diabetes.

The comparison group was identified by using propensity score analysis (23,24,25,26), which is a well-established technique for reducing the confounding effects of selection bias in observational studies. To identify a sample that was matched on multiple variables by using propensity score analysis, a logistic regression model, PROC LOGISTIC in SAS (27), was first fit that predicted the likelihood of being given a diagnosis of diabetes. Independent variables in the logistic regression model included the antipsychotic agent prescribed during the three-month prescribing period, the date that the three-month prescribing period ended, age, gender, race, income, whether the patient had comorbid mental health diagnoses, use of mental health and medical or surgical services during the three-month prescribing period, and the degree of VA service-connected disability. These variables represent patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that might affect the likelihood of receiving a diagnosis of diabetes. Other potentially important patient characteristics were not available, such as body mass index, family history, and smoking status.

The predicted probability of receiving a diagnosis of diabetes (the propensity score) was calculated for each patient in the sample on the basis of the logistic regression model. For every patient who was given a diagnosis of diabetes, three patients who did not contract diabetes and had predicted probability most nearly equal to that of the patient with diabetes were selected as comparisons. For patients in the comparison group, a pseudo-diabetes diagnosis date was constructed by taking the number of days between the end of the three-month prescribing period and the diabetes diagnosis date for the corresponding matched patient with diabetes and adding it to the end of the three-month prescribing period for the patient without diabetes.

Analysis

All patients were followed retrospectively for six months after the diabetes diagnosis date, and measures of health care costs and medication changes were constructed. Costs were broken down into mental health and non-mental health costs and by period—the three months in which a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy was prescribed, the period between the consistent regimen of antipsychotics and the diabetes diagnosis date, zero to two months after the diabetes diagnosis date, two to four months after the diabetes diagnosis date, and four to six months after the diabetes diagnosis date.

Health care costs were compared among patients with diabetes and those without. The additional cost per patient as a result of diabetes treatment that was attributable to second-generation antipsychotics was calculated by multiplying the additional cost by the attributable risk associated with each second-generation medication. The attributable risk, which was derived in a previous study (20), represents the estimated proportion of patients who were taking a second-generation antipsychotic who would not have received a diagnosis of diabetes if they had been taking a first-generation antipsychotic instead of that specific second-generation drug. Medication changes were analyzed by comparing the antipsychotic that was prescribed 90 days after the diabetes diagnosis date with the antipsychotic that was prescribed immediately before the diabetes diagnosis date.

Results

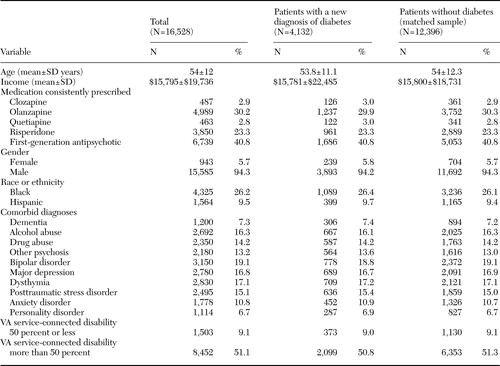

We identified 56,849 patients for whom a consistent regimen of antipsychotic monotherapy was prescribed and who had complete data for all demographic and clinical characteristics. A total of 33,040 of these patients were initially given a prescription for a second-generation antipsychotic, and 23,809 were initially given a prescription for a first-generation antipsychotic. Among these patients, 4,132 (7.3 percent) were given a diagnosis of diabetes during the follow-up period; 2,446 (7.4 percent) of these patients were initially given a prescription for a second-generation antipsychotic, and 1,686 (7.1 percent) were initially given a prescription for a first-generation antipsychotic. As shown in a previous study, the relative risk of diabetes associated with second-generation antipsychotics was significant for clozapine (hazard ratio=1.57) and olanzapine (hazard ratio=1.15) but not for risperidone (hazard ratio=1.02) or quetiapine (hazard ratio=1.20) (20). The comparison group consisted of 12,396 matched patients who did not have a diagnosis of diabetes during the follow-up period, bringing the total study sample to 16,528. Characteristics of the patients in the study sample are presented in Table 1. Differences in patient characteristics across the two groups were not statistically significant.

Medication changes

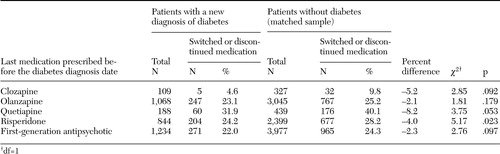

Table 2 shows the proportion of patients who switched or discontinued the antipsychotic that they were taking after the diabetes diagnosis date, by patient group. The periods examined in this analysis were the time immediately before the diabetes diagnosis date and 90 days after the diagnosis date. Differences between the patients with diabetes and those without diabetes in the proportion of patients who switched medications were small and statistically significant only for patients who were taking risperidone before the diabetes diagnosis date. The proportion of patients who switched or discontinued medication was largest for patients for whom quetiapine was prescribed (60 patients with diabetes, or 31.9 percent, compared with 176 patients without diabetes, or 40.1 percent) and smallest for patients for whom clozapine was prescribed (five patients with diabetes, or 4.6 percent, compared with 32 patients without diabetes, or 9.8 percent). Paradoxically, for each medication group the proportion of patients who switched or discontinued medication was greater among patients who were not subsequently given a diagnosis of diabetes.

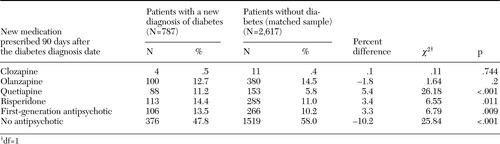

Table 3 reports the medications to which patients switched when a medication change occurred. In both the diabetes and nondiabetes groups, patients were much more likely to discontinue antipsychotic pharmacotherapy than switch to another medication. Compared with patients without diabetes, patients with diabetes were significantly less likely to discontinue antipsychotic pharmacotherapy and significantly more likely to switch to quetiapine, risperidone, or a first-generation antipsychotic. The proportion of patients who switched to clozapine or olanzapine was not significantly different between the two groups.

Costs

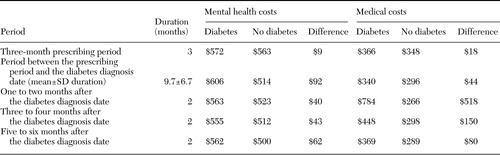

On average, after the three-month prescribing period, total VA health care costs for patients with diabetes were $3,104 more than those for patients without diabetes. Table 4 illustrates patterns of average monthly costs for mental health and non-mental health services over the entire study period, by patient group. Costs for patients with diabetes were higher both before and after the diabetes diagnosis date. Because the average follow-up time was 15.7 months (an average of 9.7 months between the end of the three-month prescribing period and the diabetes diagnosis date, and six months after the diabetes diagnosis date), this increase in cost averaged $198 per month. The bulk of this difference occurred in the expenditures for non-mental health services in the first two months after the diabetes diagnosis date. However, compared with patients without diabetes, patients with diabetes had slightly higher mental health expenditures.

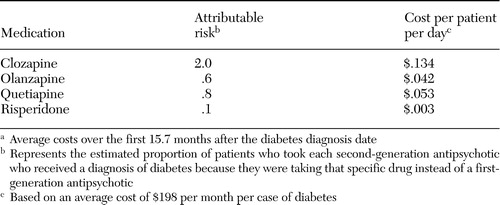

Table 5 lists the average additional daily cost per patient associated with the increased risk of diabetes that was attributable to each second-generation medication. We calculated this cost by multiplying the annual attributable risk associated with each second-generation medication (20) by the average daily additional costs ($198 divided by 30 days) among patients with diabetes. Additional costs associated with clozapine use were the highest at $.134 per treated patient per day, followed by quetiapine ($.053), olanzapine ($.042), and risperidone ($.003).

Discussion

We found very few differences in patterns of medication changes between patients with and without diabetes. The proportion of patients who switched or discontinued antipsychotic pharmacotherapy was actually smaller among patients with diabetes than among those without diabetes, although the difference was statistically significant only for patients who were taking risperidone immediately before the diabetes diagnosis date. When patients switched to another antipsychotic medication, patients with diabetes were significantly more likely to switch to quetiapine, risperidone, or a first-generation antipsychotic. Except for quetiapine, this finding is consistent with a previous study that showed that the risk of diabetes is highest for patients who receive clozapine or olanzapine and lowest for patients who receive risperidone or first-generation antipsychotics (20). Despite being statistically significant, the difference in the proportion of patients who switched to a first-generation medication after the diabetes diagnosis date was small (3.3 percent). Because of the increased risk of developing diabetes that is associated with clozapine and olanzapine, we expected that patients who developed diabetes might switch to first-generation antipsychotics, for which the risks of weight gain and diabetes are considered to be much smaller. It is possible that the limited switching was due to the fact that psychiatrists did not know that their patients had been given a diagnosis of diabetes, although the VA uses an electronic medical record that includes patients' diagnoses of medical disorders.

Compared with patients without diabetes, those who were eventually given a diagnosis of diabetes cost an average of $3,104 more per patient over the follow-up period. However, the average daily cost that was attributable to the increased risk of diabetes for a patient who was given a prescription for a second-generation antipsychotic was small, ranging from $.003 per day for risperidone to $.134 per day for clozapine (Table 4). These costs pale in comparison with the costs of the medications themselves and with other substantial health costs in this population (21). A previous study of costs of antipsychotics in the VA during fiscal year 2000 found that the average daily cost per patient was $8.26 for clozapine, $6.72 for olanzapine, $3.43 for risperidone, and $3.61 for quetiapine (28). Compared with these costs, the costs attributable to the increased risk of diabetes with some second-generation antipsychotics are small.

However, it should be noted that these attributable costs for diabetes address only the earliest phase of what may be a lifelong illness. A recent study estimated the lifetime costs associated with managing the complications of type 2 diabetes in the United States to be $47,240 per patient over 30 years (29). With attributable risks of 2.0 percent for clozapine and .6 percent for olanzapine, the lifetime diabetes costs associated with these drugs would be $959 and $298, respectively. However, it is unknown whether newly diagnosed diabetes associated with antipsychotic medications can be reversed if patients discontinue use of the medication or if they behaviorally control their weight.

Most of the increase in cost for patients with a new diagnosis of diabetes was driven by higher costs for non-mental health care. However, costs for mental health care were also higher for patients with diabetes than for those without diabetes, especially in the period before the diabetes diagnosis date. A potential explanation for the increased use and costs of mental health services is that patients with diabetes might have come to the VA more often because they were not feeling well in general but did not know why. After the diabetes diagnosis date, mental health costs declined and medical costs increased sharply.

Several limitations of the study deserve comment. First, this was an observational study, and hence causal inferences are suggestive rather than conclusive. However, because random assignment was not possible, questions about the effects of newly diagnosed diabetes on cost and pharmacotherapy can be addressed only through observational studies such as this.

There may have been cases of diabetes that were not diagnosed or that were diagnosed outside of the VA system. Because we had access only to administrative records and not to detailed clinical data, we were unable to identify these cases. Hence some of the patients in our comparison group may in fact have had diabetes.

Other limitations are associated with administrative data. Diagnoses may not be as accurate as they are in detailed clinical data, and other risk factors associated with diabetes were not available, such as body mass index, family history, and smoking status. In addition, we did not have access to laboratory data to determine whether the patient had a fasting blood glucose test or the result of the test. Information was also not available regarding the reasons for medication changes, so we could not determine whether the patient switched or discontinued medications because of weight gain and diabetes or for other reasons. Also, it is possible that patients received other medications outside the VA system.

Finally, the perspective of the study was that of the VA. Costs associated with newly diagnosed diabetes included only VA treatment costs. Any costs associated with lower quality of life or caregiver burden were not captured in this study.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the results presented here offer important insight into the consequences of newly diagnosed diabetes among patients who have schizophrenia and take antipsychotics. Diabetes does not appear to lead to substantial changes in antipsychotic pharmacotherapy, and the cost implications were negligible, although patients were followed for an average of only 15 months.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institute of Mental Health's Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Yale University in West Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Leslie is also with the Clinical Epidemiology Research Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) in West Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Rosenheck is also with the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the VA in West Haven. Send correspondence to Dr. Leslie at NEPEC 182, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). Preliminary results of this study were presented at the American Psychiatric Association's Institute on Psychiatric Services, held October 29 to November 2, 2003, in Boston.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with schizophrenia in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system, by diabetes status

|

Table 2. Patients with schizophrenia in the Department of Veterans Affairs system who switched or discontinued antipsychotic medication, by last medication prescribed before the diabetes diagnosis date

|

Table 3. New medication prescribed 90 days after the diabetes diagnosis date among patients with schizophrenia in the Department of Veterans Affairs system who switched or discontinued antipsychotic medication

|

Table 4. Average monthly mental health and medical costs in the Department of Veterans Affairs system per patient, by period

|

Table 5. Additional cost per patient for diabetes treatment attributable to second-generation antipsychoticsa

aAverage costs over the first 15.7 months after the diabetes diagnosis date

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:789–796,1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Tran PV, et al: Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders: results of an international collaborative trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:457–465,1997Link, Google Scholar

3. Small JG, Hirsch SR, Arvanitis LA, et al: Quetiapine in patients with schizophrenia: a high- and low-dose double-blind comparison with placebo: Seroquel Study Group. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:549–557,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:825–835,1994Link, Google Scholar

5. Goff DC, Posever T, Herz L, et al: An exploratory haloperidol-controlled dose-finding study of ziprasidone in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 18:296–304,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Potkin SG, Saha AR, Kujawa MJ, et al: Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with a novel mechanism of action, and risperidone vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:681–690,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Marder SR, McQuade RD, Stock E, et al: Aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia: safety and tolerability in short-term, placebo-controlled trials. Schizophrenia Research 61:123–136,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Stahl SM: Selecting an atypical antipsychotic by combining clinical experience with guidelines from clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 10):31–41,1999Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bustillo JR, Buchanan RW, Irish D, et al: Differential effect of clozapine on weight: a controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:817–819,1996Link, Google Scholar

10. Cohen S, Chiles J, MacNaughton A: Weight gain associated with clozapine. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:503–504,1990Link, Google Scholar

11. Henderson DC, Cagliero E, Gray C, et al: Clozapine, diabetes mellitus, weight gain, and lipid abnormalities: a five-year naturalistic study. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:975–981,2000Link, Google Scholar

12. Lamberti JS, Bellnier T, Schwarzkopf SB: Weight gain among schizophrenic patients treated with clozapine. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:689–690,1992Link, Google Scholar

13. Gianfrancesco FD, Grogg AL, Mahmoud RA, et al: Differential effects of risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, and conventional antipsychotics on type 2 diabetes: findings from a large health plan database. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:920–930,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, et al: Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1686–1696,1999Abstract, Google Scholar

15. Fertig MK, Brooks VG, Shelton PS, et al: Hyperglycemia associated with olanzapine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59:687–689,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Ober SK, Hudak R, Rusterholtz A: Hyperglycemia and olanzapine. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:970,1999Link, Google Scholar

17. Wirshing DA, Spellberg BJ, Erhart SM, et al: Novel antipsychotics and new onset diabetes. Biological Psychiatry 44:778–783,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Koro CE, Fedder DO, L'Italien GJ, et al: An assessment of the independent effects of olanzapine and risperidone exposure on the risk of hyperlipidemia in schizophrenic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:1021–1026,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Sobel M, Jaggers ED, Franz MA: New-onset diabetes mellitus associated with the initiation of quetiapine treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:556–557,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: Incidence of newly diagnosed diabetes attributable to atypical antipsychotic medications. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1709–1711,2004Link, Google Scholar

21. Rosenheck R, Perlick D, Bingham S, et al: Effectiveness and cost of olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia. JAMA 290:2693–2702,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Leslie DL, Rosenheck RA: From conventional to atypical antipsychotics and back: dynamic processes in the diffusion of new medications. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1534–1540,2002Link, Google Scholar

23. Rosenbaum P, Rubin D: The central role of propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70:41–55,1983Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Rosenbaum P, Rubin D: Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. American Statistician 39:33–38,1984Google Scholar

25. Rosenbaum P, Rubin D: Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Journal of the American Statistical Association 79:516–524,1985Google Scholar

26. Rubin DB: Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Annals of Internal Medicine 127:757–763,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. The logistic procedure, in SAS/STAT User's Guide: Version 8. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1999Google Scholar

28. Rosenheck R, Doyle J, Leslie D, et al: Changing environments and alternative perspectives in evaluating the cost-effectiveness of new antipsychotic drugs. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:81–93,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Caro JJ, Ward AJ, O'Brien JA: Lifetime costs of complications resulting from type 2 diabetes in the US. Diabetes Care 25:476–481,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar