Economic Grand Rounds: The Economics of the New Medicare Drug Benefit: Implications for People With Mental Illnesses

The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 established a new prescription drug benefit (Medicare Part D) that will be available to elderly and disabled beneficiaries beginning in 2006. Medicare will provide a new source of prescription drug coverage for beneficiaries who are currently covered by Medicaid or private insurance and will expand coverage to the 35 percent of beneficiaries who lack prescription drug coverage. The drug benefit will be an important source of financing for psychiatric medications and may increase the number of Medicare beneficiaries treated for mental illnesses.

The Medicare Modernization Act creates a delivery system for drug benefits that promotes choice for the consumer and competition among insurers. However, the very features of the new drug benefit plan that allow for consumer choice and plan competition may also lead to adverse selection. Adverse selection in the Medicare prescription drug benefit market could have important economic implications for the Medicare program and could create access problems for consumers, particularly individuals with chronic illnesses who have high drug costs.

Economics of adverse selection in insurance markets

Adverse selection occurs when consumers know more about their health status and their propensity to use services than their health plan (1). Individuals with high health care costs tend to enroll in health plans with generous coverage, which results in financial losses to these plans. To avoid adverse selection, health plans send signals to consumers to discourage those who are a bad risk from enrolling. These signals may include higher cost-sharing for certain services (demand-side selection behavior). For instance, deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, and annual limits for mental health services are typically more restrictive than those for other medical benefits (2). These restrictions are put in place because consumer demand for mental health services is more responsive to price and because insurers seek to avoid attracting individuals with chronic mental illnesses who have high health care costs (3).

In managed care settings, health plans may discourage high-risk individuals from enrolling through underprovision, or low-quality provision, of some services (supply-side selection behavior). For example, health plans may institute a restrictive formulary for certain drug classes to discourage high-risk individuals from choosing the plan. It is relatively straightforward to regulate plan benefit design by requiring certain minimum benefits—for example, requiring parity for mental health services. Regulating supply-side selection behavior is challenging because of the difficulty in distinguishing prudent cost control and quality improvement efforts from selection behavior (4). In the context of the Medicare drug benefit, plans may use formularies not only as a means of improving efficiency of service delivery and negotiating lower drug prices but also as a tool for selection.

Selection on the basis of mental health status

The economics literature suggests that plans will manipulate the quantity of specific health services that they provide to avoid adverse selection. Services that consumers know they have a high likelihood of using and that are positively correlated with total spending, such as mental health services, are more likely to be underprovided (4,5,6). Incentives to underprovide psychiatric medications may be even stronger than those for mental health services for several reasons. Psychiatric medications are among the most expensive classes of drugs. Antidepressants and antipsychotics ranked third and fourth in total dollar sales in 2003 (7). Serious mental illnesses are chronic and persistent, and individuals are likely to take psychiatric medications for several years. In addition, individuals with serious mental illnesses are very likely to have comorbid medical conditions, making their total drug costs very high.

In the Missouri Medicaid program, 84 percent of enrollees who used psychiatric medications were in the top quartile of total drug spending in 2004 (personal communication, Comprehensive NeuroScience Drugs, 2005). Incentives for drug plans to select on the basis of mental health status are likely to be strong, because psychiatric medications are less able to be therapeutically substituted than drugs in other classes (8). Once an individual with mental illness finds a good treatment match, his or her provider may be reluctant to switch medications and the individual will likely seek out a plan that covers the drug. The response of health plans may be to limit access to psychiatric medications to avoid adverse selection.

Key features of the plan and implications for selection

Several attributes of an insurance program can either create or attenuate selection incentives. Below, the key features of the Medicare drug benefit delivery system that relate to selection incentives are briefly reviewed.

Choice of plan

Medicare beneficiaries will have a choice of plans in their area. Beneficiaries may either enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan (Medicare managed care plan, formerly called Medicare+Choice) for all Medicare covered benefits, including prescription drugs, or they may remain in the fee-for-service Medicare program and enroll in a prescription drug only plan for Part D benefits. The goal is to have at least two prescription drug only plans available in each region.

Plan payment and risk sharing

Plans will be reimbursed on a capitated basis and will share some of the financial risk for delivering the drug benefit with the Medicare program, giving plans an incentive to control costs.

Formularies and pharmacy management tools

Medicare Advantage and prescription drug only plans are given a great deal of latitude in the use of formularies. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed guidelines to aid plans in formulary development and to guide CMS in its review of formularies submitted by plan bidders (9). CMS contracted with U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) to develop a model list of therapeutic categories and classes.

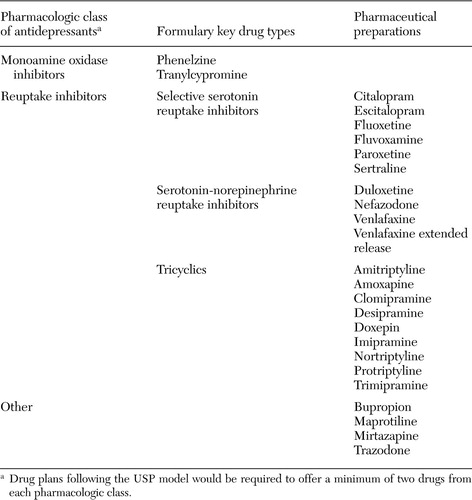

Table 1 shows the USP model for antidepressants. The Medicare Modernization Act requires plans to offer at least two drugs in each category or class. For example, a plan that chooses to follow the USP model would be required to offer a minimum of two drugs from each of three antidepressant classes: monoamine oxidase inhibitors, reuptake inhibitors, and other antidepressants. CMS guidelines further stipulate that formularies should include one drug from each "key drug type." A plan could cover generic fluoxetine but no other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or a plan could require prior authorization for brand-name antidepressants. Such formularies would achieve compliance with the statute but could substantially limit therapeutic choice, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression who require several medication trials before finding the right treatment match. Moreover, restrictive formularies could discourage individuals with depression from enrolling in these plans. Plans are also permitted to use pharmacy benefit management tools such as quantity limits, step therapy, and prior authorization to contain costs.

Benefit design

The Medicare Modernization Act establishes a standard benefit design that provides both up-front coverage and protection against high drug costs (more than $3,600 in out-of-pocket spending), with a gap in coverage for total drug costs between $2,250 and $5,100, the infamous "donut hole" (10). Plans may either offer the standard benefit design or an "actuarially equivalent" alternative. For instance, plans could create a system of tiered copayments, with lower copayments for generic drugs than for branded drugs. It is worth noting that enrollee spending on drugs that are not on a plan's formulary does not count toward an enrollee's out-of-pocket maximum cost. Individuals who are dually eligible for Medicaid and low-income beneficiaries will receive substantial subsidies to cover the premiums, deductibles, and copayments.

Discussion and conclusions

An advantage of a delivery system in which plans compete for enrollees is that Medicare beneficiaries will face a range of plan options and can choose the plan that best fits their preferences. In addition, contracting with several plans in each area encourages price competition. The flexibility given to plans to design formularies will allow plans to negotiate lower prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers. A chief disadvantage of this delivery system is that it creates strong economic incentives for plans to select enrollees on the basis of risk—that is, to discourage the enrollment of individuals who are sicker and to encourage the enrollment of individuals who are healthy. Plans may discourage the enrollment of sicker individuals through restrictive formularies or requiring prior authorization for expensive drugs. For example, a plan that lists several newer second-generation antipsychotics on its formulary would likely attract a sicker population than one that listed only two second-generation antipsychotics. As a result, meaningful coverage of prescription drugs to treat mental illnesses may erode over time.

The Medicare Modernization Act requires CMS "to review Part D formularies to ensure that beneficiaries have access to a broad range of medically appropriate drugs to treat all disease states and to ensure that the formulary design does not discriminate or substantially discourage enrollment by certain groups" (11). CMS formulary review provides a critical mechanism to ensure access to psychiatric medications in the Medicare drug benefit. Ensuring coverage of a range of medications will be particularly important for dually eligible individuals who are disabled and currently receive relatively generous drug benefits through Medicaid.

The key mechanisms through which the Medicare program may attenuate selection incentives in the drug benefit are risk adjustment of payments and risk-sharing arrangements. The effectiveness of risk adjustment in reducing selection incentives will depend on how well the risk-adjustment model predicts variation in drug spending and the weights assigned to categories of individuals with higher drug costs. Risk-adjustment models have explained only a limited portion of the variation in health spending and therefore are not likely to fully counteract selection incentives. Risk sharing between drug plans and the Medicare program for individuals with catastrophic drug costs is also likely to attenuate selection incentives.

There is an inherent tradeoff in plan reimbursement schemes between selection and efficiency (12). The more financial risk imposed on the plan the stronger the incentive to manage care efficiently and the stronger the incentive to discourage high-risk individuals from enrolling. By reducing financial risk to plans through risk sharing, Medicare may dampen incentives for plans to negotiate lower drug prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers and to manage drug use. When it comes to vulnerable populations, such as people with mental illnesses, public policy makers will need to carefully balance the goals of efficiency in service delivery and access to clinically important medications.

Dr. Donohue is affiliated with the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh, 130 DeSoto Street, Crabtree Hall A613, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15261 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., and Haiden A. Huskamp, Ph.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Sample of U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) model to aid plans in formulary development for the prescription drug benefit of the Medicare Modernization Act

1. Rothschild M, Stiglitz J: Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: an essay in the economics of imperfect information. Quarterly Journal of Economics 90:629–649,1976Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999Google Scholar

3. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Economics and mental health, in Handbook of Health Economics: Vol 1A. Edited by AJ Culyer and JP Newhouse. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 2000Google Scholar

4. Frank RG, Glazer J, McGuire TG: Measuring adverse selection in managed health care. Journal of Health Economics 19:829–854,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Pauly MV, Zeng Y: Adverse selection and the challenges to stand-alone prescription drug insurance. Frontiers in Health Policy Research 7:55–74,2004Medline, Google Scholar

6. Glazer J, McGuire TG: Optimal risk adjustment in markets with adverse selection: an application to managed care. American Economic Review 90:1055–1071,2000Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Leading 20 Therapeutic Classes by US Sales, 2003. IMS Health. Available at www.imshealth.com/ims/portal/front/articleC/0,2777,6599_42720942_44304299,00.htmlGoogle Scholar

8. Huskamp HA: Managing psychotropic drug costs: will formularies work? Health Affairs 22(5):84–96,2003Google Scholar

9. Comprehensive Listing of Drugs in the USP Model Guidelines. U.S. Pharmacopeia. Available at www.usp.org/pdf/druginformation/mmg/comprehensivedruglisting2004–12–31.pdfGoogle Scholar

10. Fact Sheet: The Medicare Prescription Drug Law. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2004. Available at www.kff.org/medicare/7044.cfmGoogle Scholar

11. Medicare Modernization Act Final Guidelines—Formularies: CMS Strategy for Affordable Access to Comprehensive Drug Coverage. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at www.cms.hhs.gov/pdps/formularyguidance.pdfGoogle Scholar

12. Newhouse JP: Reimbursing health plans and health providers: efficiency in production versus selection. Journal of Economic Literature 34:1236–1263,1996Google Scholar