Newspaper Stories as Measures of Structural Stigma

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Structural stigma and discrimination occur when an institution like a newspaper, rather than an individual, promulgates stigmatizing messages about mental illness. This study examined current trends in the news media on reporting topics of mental illness. METHODS: All relevant stories (N=3,353) in large U.S. newspapers were identified and coded during six weeklong periods in 2002. Stories were coded by themes that fit into four categories: dangerousness, blame, treatment and recovery, and advocacy action (that is, calls for public policy and action that increase the quality of care or opportunities for those with mental illness). RESULTS: Thirty-nine percent of all stories focused on dangerousness and violence; these stories most often ended up in the front section. Few stories promulgated the idea that either the person or the family was responsible for mental illness (2 percent). Instead, stories about genetic or biological or environmental causation (for example, stress and trauma) were more common (15 percent). There were equal numbers of stories about biological and psychosocial treatments (13 and 14 percent, respectively). Four percent of all treatment-related stories addressed recovery. Twenty percent of stories contained themes that fell into the broad category of advocacy action. These stories addressed the shortage of resources in the public mental health arena, the need for better care, the absence of good-quality housing, and the goal of insurance parity. CONCLUSIONS: Data on how mental illness is represented in newspapers yield a useful perspective on structural stigma and the policies and standards that are applied by the news media. These findings have implications for influencing the press.

Research has distinguished structural stigma from personal stigma (1,2,3). When we think about stigma, the type of stigma that perhaps most commonly comes to mind is personal stigma—namely, an individual psychological process that includes prejudicial attitudes and discriminatory behaviors. Sociologists have described an alternative form of prejudice and discrimination, which has been called structural stigma (4,5,6,7). This type of stigma is formed by sociopolitical forces and represents policies of private and government institutions that restrict the opportunities of the groups that are stigmatized. One of the more obvious examples is Jim Crow laws, enacted by southern states from the end of the 19th to the middle of the 20th century to limit rights of African Americans (6). In an earlier paper, we examined recent state statutes in all 50 states to describe the structural stigma of mental illness (2). In this study, we examined themes of newspaper stories as a measure of structural stigma.

Mass communication sources, including the news media, provide fundamental frameworks through which most Americans and people from developed nations come to perceive and understand the contemporary world (8). Unfortunately, when the news media frames a group in a negative light, it propagates prejudice and discrimination. Hence, whether it is intentional or not, newspapers become social structures for perpetuating stigma. Survey studies in several English-speaking countries have shown that newspapers frequently frame mental illness in a stigmatizing way (9,10,11,12,13,14). Recurring findings show that most articles discuss people with mental illness in terms of dangerousness or violent crime: as many as 75 percent of stories that deal with mental illness focus on violence (12).

Although more recent research suggests that the prevalence of these kinds of stories is diminishing, at least 30 percent of the stories continue to focus on dangerousness (14). A vast majority of the remaining stories on mental illness focus on other negative characteristics related to people with this disorder (for example, unpredictability and unsociability) or on medical treatments. Notably absent are positive stories that highlight the recovery of many persons with mental illness (14). Although the reduction in the proportion of negative stories is a positive trend, the overrepresentation of stories that perpetuate stereotypes is an example of structural stigma. These stories reflect informal industry norms applied by news editors and reporters who choose to promote sensationalistic portrayals of mental illness.

Methods used in these previous studies have limitations. First, although these studies made some effort to sample a variety of news sources, no systematic sampling plans were evident to ensure a representative collection of news stories. Our study used a sampling strategy to yield a comprehensive database that represented the population of American news stories for a specific period. Second, the coding schemes that previous studies used to identify themes in newspaper stories were generally not theory based. The coding scheme that was used in our study was based on previous concept-based work that examined common stereotypes of people with mental illness (15,16). In this way, we used findings about personal stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs that are likely to influence reporter's and editor's storylines to develop the coding scheme for structural stigma in published articles. Because this is the first national survey of its kind, we chose to anchor our measures in previous empirical work that represented our theoretical base.

Our research on stereotypes has focused on two theories. The first theory represents the impact of dangerousness. Viewing people with mental illness as possibly violent leads to fear, which, in turn, precipitates social avoidance (17,18,19,20). The second theory relates to attributions of personal blame (21). People who are viewed as responsible for their mental illness are likely to evoke anger and punishment; those who are not blamed for their illness are pitied and offered help (22,23,24,25,26).

A recent review by Wahl and colleagues (14) suggests two other theoretically important content areas for coding stories. The first area determines how stories discuss treatment. How do stories compare in their focus on biological versus psychosocial treatment? Do these discussions include recovery as a reasonable outcome? The second area has been identified by sociologists as the antithesis of structural stigma, broadly construed as affirmative or advocacy action (27). Advocacy action is defined as promoting public policy and actions that increase the opportunities for persons with mental illness. Do news stories address advocacy agendas that promote opportunities for people with mental illness? For example, do they discuss issues such as the shortage of services and the poor provision of treatments when they are provided as well as issues that have become important recently, such as housing and insurance parity. The overall coding system developed for our study will include these four main categories: dangerousness, blame, recovery, and advocacy action.

Methods

Our goal was to collect a probability sample of newspaper stories from large newspapers across America. All U.S. newspapers with daily circulation greater than 250,000 were selected for our study. Because we wanted a geographically dispersed sample of newspapers, we also selected the largest newspaper in any state where existing dailies did not have a circulation exceeding 250,000. For example, the Omaha World Herald was selected for Nebraska even though it had a daily circulation of only 196,000, because it was that state's largest newspaper. Seventy newspapers meeting these criteria were identified from circulation averages for 2002 that were listed on the Audit Bureau of Circulations Web site, an online research tool that lists all U.S. daily newspapers (28). These newspapers list their stories in toto on one of four online databases: LexisNexis (32 newspapers, or 46 percent), NewsBank (34 newspapers, or 49 percent), Dow Jones Interactive Factiva (three newspapers, or 4 percent), or Proquest (one newspaper, or 1 percent).

We searched these databases for all stories in the 70 newspapers that contained any of the following three terms: "mental," "psych," or "schizo." We excluded articles if they were about drug or alcohol abuse unless they also clearly included a mental illness issue, if they mentioned psychiatric evaluations or psychotherapy without a manifest link to mental illness, and if they had "Psycho" as part of a movie or book title. We searched for stories that fell within six-week periods that were randomly selected from every two months throughout 2002: February 24 to March 2, April 28 to May 4, July 14 to July 20, August 18 to August 24, October 13 to October 19, and December 15 to December 21. Story themes did not change notably across these six periods, so data were collapsed across the six weeks.

Coding schema

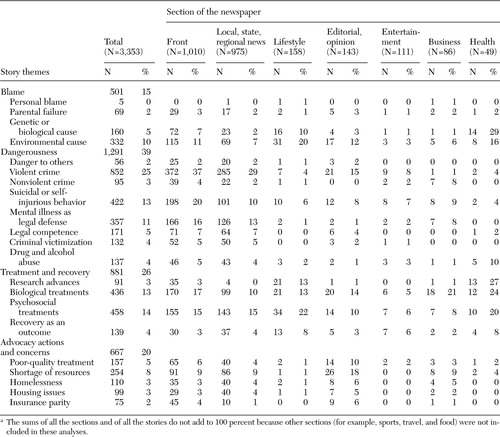

We developed a coding schema that was consistent with our theoretical framework: stigmatizing themes related to dangerousness, blame, treatment and recovery, and advocacy actions. Candidates for our coding schema were drawn from two sources. First, we used themes developed by Wahl and colleagues (14) relevant to these four categories. Second, we conducted a focus group to further develop codes for this study. The focus group included six members of mental health advocacy groups and two members from the press. The group was asked to provide examples of current and past news stories that might be construed as intentionally or unintentionally prejudicial or discriminatory toward people with mental illness. Subsequent analyses of transcripts of the focus group yielded several themes that were not found in the study by Wahl and colleagues (14). These additional themes were sorted into the four main categories that guided our study. Specific themes for each of the four categories are listed in Table 1. Several themes were not included in the analysis, which should not affect sums because the categories were not mutually exclusive. Each theme also included a paragraph-long definition to facilitate coding.

Raters coded all stories for themes. Interrater reliability was determined for 10 percent of the stories (346 stories) coded by two independent judges. Mean percent agreement for the codes was 98.2 percent.

Results

The mean±SD daily circulation of the 70 newspapers from the 50 states was 451,481±352,578, ranging from 16,755 to 2,195,805. By using the search terms outlined in the Methods section, 3,353 separate stories were identified. On average, individual papers ran 48.3±33.9 stories related to mental illness during the period studied. The number of stories ranged from five to 186. As shown in Table 1, stories were categorized by theme and newspaper section. In some instances, the number of stories in a category was less than the sum of stories for the category's themes. For example, 501 stories fell under the category of blame, although 566 stories were listed under this category's themes. This result occurred when a single story was sorted into more than one theme.

As a whole, themes related to dangerousness accounted for the most stories (39 percent). Several different themes made up the dangerousness category. When we searched for themes related to danger to others, few articles emerged (2 percent). However, 25 percent of all stories had text related to violent crime, the single most prevalent theme found in our analysis. The crime theme was further expanded if the 11 percent of stories that dealt with mental illness as a legal defense are taken into account. Also, 13 percent of the stories were related to suicidal or self-injurious behavior. Far fewer stories (4 percent) dealt with mental illness as a variable related to being victimized by crime.

Stories on crime and violence were most prevalent in the front section of the newspaper, thereby augmenting the possible impact of these stories. Fifteen percent of editorials and other opinion pieces dealt with violent crimes, suggesting that columnists who write about mental health issues frequently broached concerns about violence. One might have expected that the entertainment section would have a relatively high number of stories that focused on dangerousness because of the prominent association between violence and mental illness in movies and on television (13). However, stories in the entertainment section did not focus on dangerousness more often than any of the other categories.

Fortunately, our findings showed that few stories attributed mental illness to parental misbehavior (2 percent). Even fewer stories blamed mentally ill persons for their illness (less than 1 percent). Five percent of the stories discussed genetic or biological causes. The most stories in this category dealt with environmental causes (10 percent), including trauma and job stress. Stories about genetic causes were most frequently found in the health section (14 of 160 stories, or 9 percent). Stories about environmental causes were frequently seen in the lifestyle section (31 of 332 stories, or 9 percent) and the health section (eight of 332 stories, or 2 percent).

Twenty-six percent of stories were related to treatment and recovery. Most were about biological treatments (13 percent) and psychosocial treatments (14 percent). Four percent of stories focused on recovery as an outcome; however, this theme accounted for only 16 percent of the stories in the category of treatment and recovery. The news media may not be adequately informing the public about the role of recovery in treatment. In terms of frequency, most stories about research and treatment were found in the health section of newspapers. Biological treatments were also prominently discussed in the front section and, interestingly, in the business section. The latter finding in part represents discussion by pharmaceutical companies of the impact of new products on psychiatric disorders. Psychosocial treatments were also prominent in the front and lifestyle sections.

Twenty percent of all articles dealt with advocacy actions. The single largest theme in this category was shortage of resources; these themes were most prevalent in editorials and opinion pieces. Five percent of stories were related to poor quality of treatment. Themes on housing and homelessness were present in 6 percent of stories. Even though insurance parity is a prominent issue on the agenda for mental health advocacy, only 2 percent of articles dealt with this theme.

Discussion

This study used a probability sample to represent the population of stories published in large newspapers across the United States in 2002. Such a comprehensive data set allowed us to provide a snapshot of negative attitudes that represent the stigma of mental illness as well as positive messages that may counter it. Good and bad news were found in terms of the dangerousness category. In all, only 39 percent of the stories were related to dangerousness, smaller than the 50 to 75 percent of stories reported in earlier research (9,12) but consistent with the approximately 30 percent of stories found by Wahl and colleagues (14). However, more stories fell into the dangerousness category than any other category. Hence, the public is still being influenced with messages about mental illness and dangerousness. Findings suggest the complexity of these results. A majority of stories are about violent crime against others or legal defenses related to mental illness. However, stories in this group also included themes of suicidal or self-injurious behaviors and nonviolent crimes. Stories related to dangerousness often ended up in the front sections of newspaper, making them more visible to readers.

An important question to consider, which was not addressed by these data, is whether the news media is influencing public opinion by focusing on the dangerousness of people with mental illness or whether reporters are merely reflecting an important crime statistic. Research has shown that people with mental illness are two to six times as likely as matched control groups to commit violence (29,30,31,32,33,34). Hence, some advocates would assert that the news media is reflecting only the level of dangerousness that exists among people with mental illness (35,36). However, when these numbers are considered in terms of base rates, one finds mental illness to be a poorer predictor of violence than demographic variables, such as age, gender, and race or ethnicity. For example, data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study have shown that males are 300 percent as likely as people with mental illness to commit a violent act (16). Yet the public is more likely to view people with mental illness as dangerous (13). We would argue that the focus of the news on violent crime is one social factor that might account for this disparity.

Findings from our study suggest that stigmatizing themes related to blame were relatively rare. Only five stories out of 3,353 included a theme consistent with personal blame. This finding is good news because previous findings have suggested that adults were likely to view people with mental illness as more responsible for their condition than those with other health disorders (37,25). Reporters also rarely used parental misbehavior as a theme. Although family members view themselves as being victims of public stigma (38,39,40), our findings show this is not the case. Instead, our findings are consistent with those of a public survey of an American probability sample, which found that only a small proportion of the public blamed parents for their child's mental illness (unpublished manuscript, Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Miller FE, 2004). Instead of focusing on personal or parental blame, stories seemed to focus on biological or environmental causes. Surprisingly, despite the proclamation by President George H. W. Bush to designate the 1990s as the Decade of the Brain, which, in part, sought to frame mental illness as a brain disorder, more than twice as many stories addressed environmental rather than biological causes.

Far more newspaper stories included themes related to treatment and recovery (26 percent) than themes related to blame (15 percent). Many of these stories reviewed biological and psychosocial treatments, and 3 percent of the stories included information about research advances. These stories frequently appeared in the health or lifestyle sections of the newspaper. Unfortunately, only a small portion of these stories included statements about recovery as an outcome. Because recovery is a relatively new principle guiding mental health services, which may counter much of the stigma of mental illness (41,42), reporters might use stories about treatment as an opportunity to spread information about this positive outcome.

Twenty percent of the stories addressed issues relevant to advocacy action. Most prominent among these were stories about the shortage of resources and the poor quality of care. Six percent of the articles reviewed housing and homelessness issues. Many of these were presented as editorials or opinion pieces, which suggests that better mental health care is a priority of newspaper management. A question that is difficult to answer here is how many articles about a specific advocacy action is enough. From the vantage point of an advocate, only 75 articles on insurance parity among 3,353 stories seem too few. It is up to advocates to partner with reporters to increase their newspapers' focus on these advocacy issues.

Several limitations of this study need to be considered in future research. First, and perhaps the greatest problem, resides in our coding schema. We reduced the complexity of several-hundred-word stories into judgments about whether a specific stigmatizing or advocacy theme was present. These findings need to be augmented by more qualitative methods.

Second, the sample of stories that was the basis of this analysis was also limited by the search terms that we used. Although our focus group agreed that "mental," "psych," and "schizo" were appropriately broad search terms, some stories related to mental illness stigma were not identified with these search terms. A separate, smaller study needs to compare output when different search terms are used.

Third, despite our efforts to achieve a probability sample, the sample that we ultimately collected is still biased. Coding stories from large newspapers excludes the kind of information that small and local newspaper presses might provide. Hence, future research needs to examine themes of stories from small presses, too.

Fourth, the reader needs to keep in mind that newspapers are only a part of the information media. Radio and television news are equally if not more prominent as information sources in America. Research needs to not only systematically survey the quality of stories in these media, but they must also examine how the form of the information (printed word and picture compared with sound bite compared with video) has an impact on the message.

Conclusions

We began this paper by arguing that patterns of newspaper articles represent the structural stigma of mental illness. We end by considering how the data collected for this paper—information about newspaper themes —yield a useful perspective on structural stigma and its effect on the social sphere.

Summaries of newspaper stories are important for advocacy groups that seek to change the information the public is given about mental illness. These summaries provide direction for advocacy efforts. From this survey, we discovered that stories about danger and crime are waning, although they are still the single largest focus among stories about mental illness. Advocates need to continue to educate reporters about this problem. The media seem to be replacing stories about personal and parental blame with stories about genetic causes and environmental stressors. This finding suggests that public attitudes are changing in terms of causality ideas. Recovery is beginning to be discussed in the literature, but advocates need to encourage reporters to do more. The need for articles about advocacy actions should be reinforced among reporters.

This paper also suggests that cross-sectional analyses of the American news media should be continued on a regular basis to determine how the news media are addressing mental health concerns in America. In some ways, our findings, compared with those of previous studies that were conducted at least ten years ago, suggest that newspapers are reporting fewer stories about persons with mental illness as being dangerous and more stories that have advocacy themes (9,12). This kind of analysis needs to be repeated every couple of years to determine whether such positive trends continue.

Dr. Corrigan, Dr. Watson, Ms. Gracia, and Ms. Slopen are affiliated with the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, 1033 University Place, Evanston, Illinois 60201 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Rasinski is with the National Opinion Research Center in Chicago. Dr. Hall is with the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill in Alexandria, Virginia.

|

Table 1. Themes of stories on mental illness from 70 major newspapers across the United States, by section of the newspaper in which the stories appeared a

a The sums of all the sections and of all the stories do not add to 100 percent because other sections (for example, sports, travel, and food) were not included in these analyses.

1. Corrigan P, Markowitz FE, Watson A: Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:481–492, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Heyrman ML, et al: Structural stigma in state legislation. Psychiatric Services 56:557–563, 2005Link, Google Scholar

3. Link BG, Phelan JC: Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27:363–385, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Hill RB: Structural discrimination: The unintended consequences of institutional processes, in Surveying Social Life: Papers in Honor of Herbert H. Hyman. Edited by O'Gorman HJ. Middletown, Conn, Wesleyan University Press, 1988Google Scholar

5. Merton RK: The bearing of empirical research upon the development of social theory. American Sociological Review 13:505–515, 1948Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Pincus FL: From Individual to Structural Discrimination in Race and Ethnic Conflict: Contending Views on Prejudice, Discrimination, and Ethnoviolence. Edited by Pincus FL, Ehrlich HJ. Boulder, CO, Westview Press, 1999Google Scholar

7. Wilson WJ: The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990Google Scholar

8. Anderson A: Media, Culture, and the Environment. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1997Google Scholar

9. Day DM, Page S: Portrayal of mental illness in Canadian newspapers. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 31:813–817, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Matas M, El-Guebaly N, Harper D, et al: Mental illness and the media: II. Content analysis of press coverage of mental health topics. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 31:431–433, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Philo G, Secker J, Platt S, et al: The impact of the mass media on public images of mental illness: media content and audience belief. Health Education Journal 53:271–281, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Shain R, Phillips J: The stigma of mental illness: labeling and stereotyping in the news, in Risky Business: Communicating Issues of Science, Risk, and Public Policy. Edited by Wilkins L, Patterson P. New York, Greenwood Press, 1991Google Scholar

13. Wahl OF: Media Madness: Public Images of Mental Illness. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1995Google Scholar

14. Wahl OF, Wood A, Richards R: Newspaper coverage of mental illness: is it changing? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 6:9–31, 2002Google Scholar

15. Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC, et al: An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:162–179, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Corrigan PW, Rowan D, Green A, et al: Challenging two mental illness stigmas: personal responsibility and dangerousness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 28:293–310, 2002Google Scholar

17. Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H: The effect of violent attacks by schizophrenic persons on the attitude of the public towards the mentally ill. Social Science and Medicine 43:1721–1728, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Levey S, Howells K: Dangerousness, unpredictability, and the fear of people with schizophrenia. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry 6:19–39, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Link BG, Cullen FT: Contact with the mentally ill and perceptions of how dangerous they are. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 27:289–302, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Wolff G, Pathare S, Craig T, et al: Community attitudes to mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:183–190, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Weiner B: Judgments of Responsibility: A Foundation for a Theory of Social Conduct. New York, NY, Guilford Press, 1995Google Scholar

22. Graham S, Weiner B, Zucker GS: An attributional analysis of punishment goals and public reactions to OJ Simpson. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23:331–346, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Menec VH, Perry RP: Reactions to stigmas among Canadian students: testing attribution-affect-help judgment model. Journal of Social Psychology 138:443–453, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Steins G, Weiner B: The influence of perceived responsibility and personality characteristics on the emotional and behavioral reactions to people with AIDS. Journal of Social Psychology 139:487–495, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Weiner B, Perry RP, Magnusson J: An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55:738–748, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Zucker GS, Weiner B: Conservatism and perceptions of poverty: an attributional analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 23:925–943, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Pincus FL: The Case for Affirmative Action in Race and Ethnic Conflicts: Contending Views on Prejudice, Discrimination, and Ethnoviolence. Edited by Pincus FL, Ehrlich HJ. Boulder, Westview Press, 1999Google Scholar

28. Marketing Intelligence for Intelligent Marketers. Audit Bureau of Circulations. Available at www.accessabc.comGoogle Scholar

29. Corrigan PW, Watson AC: What factors explain how policy makers distribute resources to mental health services? Psychiatric Services 54:501–507, 2003Google Scholar

30. Link B, Andrews H, Cullen F: The violent and illegal behavior of mental patients reconsidered. American Sociological Review 57:275–292, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Stueve A, Link BG: Violence and psychiatric disorders: results from an epidemiological study of young adults in Israel. Psychiatric Quarterly 68:327–342, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, et al: Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:761–770, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

34. Wessely S: The epidemiology of crime, violence, and schizophrenia. British Journal of Social Psychiatry 170:8–11, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Satel S, Jaffe DJ: Violent fantasies. National Review 20:33–37, 1998Google Scholar

36. Torrey EF: Violent behavior by individuals with serious mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:653–662, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

37. Corrigan PW, River L, Lundin RK, et al: Stigmatizing attributions about mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology 28:91–102, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Angermeyer MC, Schulze B, Dietrich S: Courtesy stigma: a focus group of relatives of schizophrenia patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:593–602, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Phelan JC, Bromet EJ, Link BG: Psychiatric illness and family stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:115–126, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Wahl OF, Harman CR: Family views of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:131–139, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990's. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:11–23, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Ralph RO, Corrigan PW: Recovery in Mental Illness: Broadening Our Understanding of Wellness. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association Press, 2004Google Scholar