Consumers' Goals in Psychiatric Rehabilitation and Their Concordance With Existing Services

Abstract

The objective of this study was to describe the rehabilitation goals of 165 consumers with serious mental illness who were living in the community and to assess the level of concordance between the consumers' perceived importance of their goals and the services they received to help them meet those goals. A structured interview was used to facilitate the expression of rehabilitation goals by consumers in the psychiatric rehabilitation program of a hospital in Montreal, Canada. The most frequently mentioned rehabilitation goals pertained to improving consumers' financial situation, physical health, cognitive capacities, and symptoms. Among these goals, the level of concordance was highest for services addressing symptoms and lowest for religious or spiritual goals.

Matching services to consumers' goals is an essential component of psychiatric rehabilitation (1). Self-concordant goals increase a person's motivation, enable individuals to reap greater satisfaction from the attainment of these goals, and can improve the person's sense of empowerment (1,2,3,4).

Consumers with serious mental illness can at times need help in identifying their rehabilitation goals (5). A comprehensive structured interview such as the Client Assessment of Strengths, Interests and Goals (CASIG-SR) (6) can elicit goals pertaining to all aspects of psychiatric rehabilitation and help in the design of a collaborative treatment program. It has been recommended that the consumer-perceived value of goals be considered (7,8), as well as their perceived adequacy of the services offered in relation to their goals (8).

The objectives of the study reported here were to describe the rehabilitation goals of consumers with serious mental illness living in the community and to assess the concordance between the perceived importance of the goals and the services received.

Methods

This study was conducted within the psychiatric rehabilitation program of the Douglas Hospital in Montreal, Canada, from August 2001 to July 2002. The 165 participants who consented to this study had mostly DSM-IV diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (129 participants, or 78 percent) and affective disorder (18 participants, or 11 percent). A total of 104 participants (63 percent) were men, 137 (83 percent) were single, 127 (77 percent) had no children, and 136 (82 percent) were white. The racial composition of the remainder of the sample was 11 percent Asian, 3 percent African or Caribbean, 2 percent First Nations, and 1 percent Latino. The mean±SD age of the participants was 43±11.6 years, and their average number of years of education was 11±3. Interviews were conducted either in French (67 participants) or in English (98 participants).

Data on consumers' rehabilitation goals were collected by using the CASIG-SR (6). CASIG-SR is a comprehensive functioning assessment that addresses most psychiatric rehabilitation treatment domains—community living skills, cognitive skills, medication issues (compliance and side effects), quality of life and treatment, symptoms, consumers' rights, and unacceptable community behaviors. Each scale ends with a yes-or-no question pertaining to that domain. For the symptoms, side effects, and community behaviors subscales, the goal question is asked only if the consumer mentions having suffered from the symptom or side effect or engaging in the specific behavior during the past three months.

The assessment also elicits goals in five broad areas—residence, finances, relationships, religion or spirituality, and physical and mental health—with open-ended questions. For example, "Would you like to improve your living situation in the next year? If yes, how would you like to improve your living situation?"

Initially, all participants answered the CASIG-SR, and all clinicians were given a copy of their clients' answers so that they could use this information to adapt the treatment plans accordingly. When the participating consumers were recontacted three months later, their individual goals had been transcribed to a "concordance" questionnaire. For each goal, the participant was asked, "To what extent is working to achieve your goal important to you at this time, on a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 being not important at all and 4 being very important?" The next question was, "To what extent do you consider that the services (or treatments) that you are currently receiving help you to achieve this goal, on a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 being not at all and 4 being a lot?" If a goal had already been met by the services, a perfect concordance score was given.

It is possible to calculate a concordance score whenever the perceived importance of an item needs to be compared with the environment's delivery of that same item (9). In our study, concordance was measured with use of the following equation: 1 - (importance of goal - help from service)/importance of goal. A score of 1 indicates perfect concordance—that is, the services offered match the level of importance of the goal. A score greater than 1 means that the services offered are exceeding those needed in regard to the level of importance of the goal, and a score less than 1 means that the services are not helping achieve the goal to the level desired. The closer the score is to 0, the less likely the services offered are meeting the consumer's goal.

Results

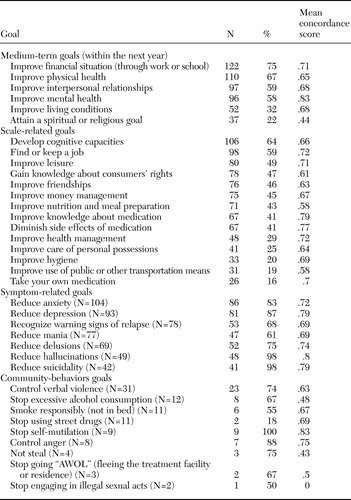

The mean±SD number of goals mentioned per consumer was 12.38±5.62. All the goals extracted from the CASIG-SR are listed in Table 1, along with the frequency of each goal in the study sample. The broader goals most frequently mentioned were to improve one's financial situation, physical health, relationships, and mental health. Examples of specific answers included reducing medication dosage, living alone, and working.

Improving one's cognitive capacities (attention, memory, or problem-solving abilities) and obtaining or keeping a job were often mentioned as goals. Consumers who had specific symptoms or problematic community behaviors frequently also mentioned improvement in these behaviors as goals.

Certain unacceptable community behaviors (self-mutilation and anger) as well as clinical goals (improving mental health, increasing knowledge about medication, decreasing side effects, and diminishing hallucinations, depressive symptoms, and suicidal thoughts) received high concordance scores. Apart from certain unacceptable community behaviors—stealing, going "AWOL" (fleeing the treatment facility or residence), and excessive drinking—which had a low frequency of occurrence, the lowest concordance scores pertained to spiritual or religious goals, nutrition or meal preparation goals, and public transportation goals. The mean concordance score for the sample was .71±.24, with a range from .25 to 1.5.

We wanted to investigate the differences between individuals with average concordance scores above, below, or close to 1. One-way analyses of variance on socioeconomic and CASIG-SR scores revealed differences on the cognitive deficits and quality-of-life subscales (F=3.46, df=2, 107, p<.05; F=3.54, df=2, 107, p<.05). Post hoc analyses showed that participants who had high concordance scores also had higher scores on the quality-of-life subscale (t= 2.04, df=103, p<.05) and lower scores on the cognitive deficits subscale (t= -2.26, df=103, p<.05) compared with participants who had low concordance scores.

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this study was to determine the rehabilitation goals of individuals with serious mental illness and to assess whether the current rehabilitation services were helping them to meet those goals. The results suggest that when consumers are specifically asked about multiple potential rehabilitation goals, they can generate many goals, whereas open-ended questions typically prompt fewer answers (10). The study findings also further support the importance of assessing the subjective value of each goal and of the services received (8). The generalizability of these results is of course limited by the use of a convenience sample from a single Canadian catchment area.

The most frequently mentioned goals pertained to areas that should be addressed by psychiatric services—improving one's financial situation, physical health, and mental health. The higher concordance scores that were noted for clinical goals and for behavior goals—self-mutilation and anger—support the findings of Fisher and colleagues (1) that services are often better geared toward specific psychiatric symptoms or behaviors than toward other goals, such as religious or spiritual goals, or the acquisition of living skills, such as nutrition and transportation skills. The concordance score seems to reflect a form of satisfaction, because individuals who attained a high concordance score also attained a high score on quality of life and complained less of cognitive difficulties. Rehabilitation services should systematically assess consumers' goals in order to offer services that meet each consumer's most important goals.

Dr. Lecomte is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Dr. Wallace is visiting professor of medical psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, Intervention Research Center for Schizophrenia. Dr. Perreault and Dr. Caron are associate professors of psychiatry at McGill University in Montreal. Send correspondence to Dr. Lecomte at 828 West Tenth Avenue, Room 214, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V5Z 1L8 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Rehabilitation goals and related concordance scores in a sample of 165 clients of a psychiatric rehabilitation program

1. Fisher EP, Shumway M, Owen RR: Priorities of consumers, providers, and family members in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 53:724–729, 2002Link, Google Scholar

2. Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ: Goal striving, need, satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76:482–497, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Corrigan PW: Empowerment and serious mental illness: treatment partnerships and community opportunities. Psychiatric Quarterly 73:217–228, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Young SL, Ensing DS: Exploring recovery from the perspective of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:219–231, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Rudnick A: The goals of psychiatric rehabilitation: an ethical analysis. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25:310–313, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wallace CJ, Lecomte T, Wilde J, et al: CASIG: a consumer-centered assessment for planning individualized treatment and evaluating program outcomes. Schizophrenia Research 50:105–119, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cradock JA, Young AS, Forquer SL: Evaluating client and family preferences regarding outcomes in severe mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 29:257–261, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Crane-Ross D, Roth D, Lauber BG: Consumers' and case managers' perceptions of mental health and community support service needs. Community Mental Health Journal 36:161–178, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Katzell RA: Personal values, job satisfaction, and job behavior, in Man in a World at Work. Edited by Borrow H. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1964Google Scholar

10. Hodges JQ, Segal SP: Goal advancement among mental health self-help agency members. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:78–85, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar