Brief Reports: Obstacles and Opportunities in Providing Mental Health Services Through a Faith-Based Network in Los Angeles

Abstract

This study surveyed attitudes toward mental health services and barriers to providing these services within the agencies of QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership, a network of faith-based organizations, and parish nurses who provided health care in a low-income, ethnically diverse area of Los Angeles. Representatives from 42 organizations responded. Informal counseling was the most frequently provided service (57 percent); yet only 19 percent reported that counselors had at least a moderate amount of training. Although 69 percent felt that referrals to nonreligious counselors were appropriate, 50 percent were reluctant to collaborate with government agencies. Barriers to providing mental health services included limited professional training, reluctance to partner with government programs, and financial and staffing limitations.

Faith-based providers are the only source of care for some persons with mental disorders (1,2). Initiatives exist to provide faith-based care, including mental health services, and recent federal legislation encourages implementing such initiatives (3). However, little is known about the capacity and willingness of faith-based organizations to provide mental health services or the compatibility of these services with the organizations' religious values. We explored attitudes toward mental health services and barriers to implementing such services within a faith-based health network to assess whether it is desirable and feasible to implement these services.

Implementing mental health services within religious organizations could benefit some high-risk populations, such as recent immigrants, because they have limited access to medical services but high rates of participation in religious organizations. Furthermore, religious organizations possess tangible resources, such as meeting space and staff members, as well as intangible resources, such as values of hope, healing, and community (4,5). Some faith-based communities also have health screening and education programs that could be extended to include mental health services (5,6).

Potential obstacles to providing mental health services within religious organizations also exist. The constitutionality of faith-based community initiatives has been questioned because of laws regarding church-state separation (7). Disputes over the appropriate roles of clergy members and health professionals and over moral and health-related interpretations of behavior raise ethical questions (5,7).

Methods

We administered a survey to the 56 member organizations of QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership. QueensCare is a nonprofit public charity that provides health care for low-income uninsured residents of Los Angeles County and is an umbrella organization that partners with churches, faith-based nonprofit organizations, and religious schools. Each partner community works closely with a parish nurse employed by QueensCare to assess the health care needs of community members and develop creative ways to meet these needs, such as hypertension screenings, and parenting classes.

In 2000 QueensCare invited leaders of its partner organizations—including pastors, counseling ministers, and directors of nonprofit organizations and religious schools—and parish nurses to participate in the survey. A cover letter explaining the survey was included, along with a self-addressed stamped envelope. No payment was offered to respondents. The survey asked about the respondent's educational background, particularly counseling training. The survey also asked about the demographic characteristics of the organization and the persons that it serves, whether staff who provide counseling are trained, referral practices, and personal understanding of mental health issues. The institutional review board of the University of California, Los Angeles, granted approval and confidentiality was guaranteed. We received 42 completed surveys (75 percent response rate) between March 2000 and March 2001.

Results

A majority of respondents were pastors and priests (22 respondents, or 52 percent), 13 respondents (31 percent) were nurses, and seven (17 percent) were counseling ministers, school leaders, or directors of nonprofit organizations. The most frequently reported denomination of the organizations was Roman Catholic (13 of 42 respondents, or 30 percent), followed by Congregationalist (five of 42 respondents, or 12 percent). In answering demographic questions, nurses referred to the congregation in which they were active members.

Of the 42 religious organizations surveyed, ten respondents (24 percent) reported that fewer than 100 persons typically attended services at the church or its associated organization, whereas nine respondents (21 percent) reported attendance of more than 1,000. Twenty-three (55 percent) reported that more than 30 percent of the community served was Hispanic, 20 (48 percent) reported that more than 30 percent of the community was white, and eight (19 percent) reported that more than 30 percent was Asian American and Pacific Islander. One respondent (2 percent) stated that more than 30 percent of the community served was black, and an additional 12 (29 percent) stated that blacks made up between 10 and 30 percent of the community.

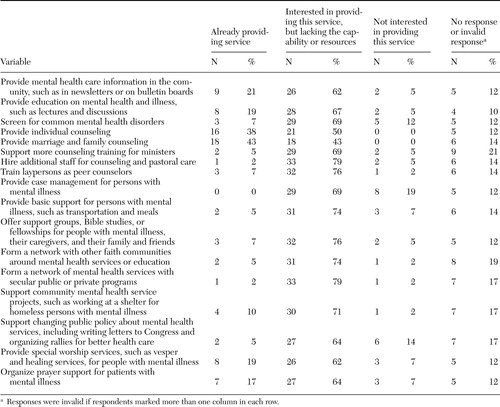

A majority of respondents believed that there is a demand for mental health services within their communities (30 respondents, or 71 percent) and that providing such services is an appropriate ministry (33 respondents, or 79 percent). However, a wide range of views was found regarding spirituality and mental illness. For example, 15 respondents (36 percent) said that it was definitely or mostly true that faith healing was an appropriate way to treat mental illness, whereas 14 (33 percent) felt that this statement was mostly or definitely false. Thirteen respondents (31 percent) felt that their community had less stigmatizing views of persons with mental illness than society overall, whereas 16 (38 percent) indicated that more stigma existed in their faith communities, and 12 respondents (29 percent) answered "do not know." Table 1 lists various mental health services offered by the organizations surveyed. Informal counseling was the most frequently provided service (24 respondents, or 57 percent); yet only eight respondents (19 percent) reported that counselors had at least a moderate amount of training.

More than half the respondents (26 participants, or 62 percent) reported that they somewhat frequently or frequently referred members to support groups, nonreligious counselors, religious counselors, primary care clinicians, psychiatrists, and county mental health departments. All respondents had referred persons to at least two of these sources. A majority (29 participants, or 69 percent) thought that it was appropriate to refer persons to nonreligious counselors, but only 21 (50 percent) were willing to partner with government agencies.

Common barriers to implementing mental health programs were lack of money (32 respondents, or 76 percent), a limited number of staff members and volunteers (29 respondents, or 69 percent), and lack of training and education (24 respondents, or 57 percent). Other barriers were lack of demand from community members (eight respondents, or 19 percent) and lack of support from community members (11 respondents, or 26 percent).

Discussion

Most representatives of faith communities who responded to this survey were interested in providing mental health services and thought that it was appropriate to do so. However, considerable variability was seen in attitudes toward mental illness. Some respondents were oriented toward a medical model of mental illness and intervention. In contrast, others viewed mental illness as more of a spiritual or moral problem. Furthermore, some respondents emphasized the importance of strategies, such as exorcism or faith healing that are not considered to be allopathic medical treatments.

Overall a majority envisioned that various mental health programs would be desirable in their communities. Moreover, many had at least informal experience with providing pastoral counseling. We do not know what methods were used in these counseling sessions or the clinical characteristics of the clients. Exploring these issues further will be important in assessing the potential role of pastoral counseling as a mental health service.

Respondents indicated that their faith communities referred persons to a variety of mental health services. Respondents suggested that they would partner with most agencies, although half were reluctant to partner with government services. This finding seems to be an important area for further research. Partnering with other stakeholders may be one way to address barriers to implementing programs. For example, collaboration may facilitate access to evidence-based programs for low-income and minority populations (8,9).

This is a descriptive pilot study and, as such, has several limitations. We relied on self-report measures. The participants were from one faith-based network in one community, and the results should not be generalized. Although there is a large body of literature on faith-based interventions for general areas of health (10), the literature does not focus on mental illness.

Although the survey represents a preliminary step, conducting this survey and providing feedback to QueensCare helped stimulate a proposal for a mental health services Medicaid contract in Los Angeles County.

Conclusions

We investigated the obstacles and opportunities in providing mental health services within the QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership, which serves a population with substantial barriers to obtaining services. Several different views on mental illness and its relationship to religious practices came to light. In particular, counseling emerged as a frequently performed, yet largely informal, service. Referrals to outside services were common, even to nonreligious agencies. However, a reluctance to partner with government agencies emerged as one barrier, along with lack of money, training, and personnel. Nonetheless, most respondents expressed a strong interest in providing mental health services and showed a willingness to form partnerships. This conclusion merits further research, as faith-based mental health care may provide one avenue for bringing needed mental health services to low-income, ethnically diverse communities.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the UCLA/ RAND Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders and by grant MH-0546-23 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Klap and Dr. Wells are affiliated with the Health Services Research Center and Dr. Dossett and Dr. Wells are with the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Ms. Fuentes is with QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership in Los Angeles.Send correspondence to Dr. Klap at the Department of Psychiatry, UCLA, 10920 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 300, Los Angeles, California 90024 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Survey of 42 representatives of religious organizations to determine whether they provided various mental health services and whether they were interested in providing these services

1. Millet PE, Sullivan MA, Schwebel AI, et al: Black Americans' and White Americans' views of the etiology and treatment of mental health problems. Community Mental Health Journal 32:235–242, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mikyong KG: Conceptualization of mental illness among Korean-American clergymen and implications for mental health service delivery. Community Mental Health Journal 29:405–412, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. Available at www.whitehouse.gov/government/fbciGoogle Scholar

4. Foege W: The vision of the possible: what churches can do, in Second Opinion: The Church's Challenge in Health Care. Edited by O'Connell LJ. Chicago, Ill, Park Ridge Center for the Study of Health, Faith, and Ethics, 1990Google Scholar

5. Carter R: A voice for the voiceless: the church and the mentally ill, in Second Opinion: The Church's Challenge in Health Care. Edited by O'Connell LJ. Chicago, Park Ridge Center for the Study of Health, Faith, and Ethics, 1990Google Scholar

6. Emmons KM: Behavioral and social science contributions to the health of adults in the United States, in Promoting Health. Edited by Smedley BD, Syme SL. Institute of Medicine, National Academic Press, Washington, DC, 2000Google Scholar

7. The Case Against Charitable Choice. Anti-Defamation League, 2004. Available at www.adl.org/charitable_choice/charitable_choice_a.aspGoogle Scholar

8. Wells KB: The design of Partners in Care: evaluating the cost-effectiveness of improving care for depression in primary care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:20–29, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al: Treating depression in predominately low-income young minority women. JAMA 290:57–65, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies From Social and Behavioral Research. Edited by Smedley BD, Syme SL. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2001Google Scholar