The Imam's Role in Meeting the Counseling Needs of Muslim Communities in the United States

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Muslims are one of the most rapidly growing minority groups in the United States and have experienced increased stress since September 11, 2001. The purpose of this study was to elucidate the roles of imams, Islamic clergy, in meeting the counseling needs of their communities. METHODS: An anonymous self-report questionnaire was mailed to 730 mosques across the United States. RESULTS: Sixty-two responses were received from a diverse group of imams, few of whom had received formal counseling training. Imams reported that their congregants came to them most often for religious or spiritual guidance and relationship or marital concerns. Imams reported that since September 11, 2001, there has been an increased need to counsel persons for discrimination. An increased need to counsel persons who were discriminated against was reported by all imams with congregations in which a majority are Arab American, 60 percent of imams with congregations in which a majority are South Asian American, and 50 percent of imams with congregations in which a majority are African American. CONCLUSIONS: Although imams have little formal training in counseling, they are asked to help congregants who come to them with mental health and social service issues. Imams need more support from mental health professionals to fulfill a potentially vital role in improving access to services for minority Muslim communities in which there currently appear to be unmet psychosocial needs.

The U.S. Surgeon General found a significant need for mental health providers to address stigma, discrimination, distrust, and differences in culture-specific experiences when they respond to the mental health problems of persons from minority communities (1,2). Muslims, with an estimated population of six to nine million, are one of the most rapidly growing minority groups in the United States and are an ethnically diverse group (3). Muslims have faced increased discrimination as a minority group after the events of September 11, 2001, and their aftermath (4). It is not well known whether the need for mental health services has increased among Muslims or what resources are available to meet those needs.

Five decades of research have found that clergy often serve as first-line mental health care providers and facilitators to help communities gain access to a larger network of mental health services (5,6,7,8), particularly in minority communities (9). A recent analysis of data from the National Comorbidity Survey found that clergy continue to provide more mental health care than psychiatrists, including treatment of people with serious mental illnesses (10).

Previous research on the role of clergy members in meeting psychiatric counseling needs has been conducted with Christian and Jewish clergy members (11,12,13,14,15) but not with imams, who constitute clergy of the third Abrahamic faith, Islam. As with Christian and Jewish clergy members, the traditional roles of imams are to lead prayers, deliver sermons, conduct religious ceremonies, and provide religious and spiritual guidance (16).

Muslims consider Islam to be central to their way of life and place great value on the integrity and functioning of the family. Thus, when Muslims have marital or family problems, they might consult with their imams. In order to help community members with their problems, the religious leaders would be expected to reference and interpret The Qur'an (sometimes transliterated as The Koran) and The Hadith, which are Holy Scriptures of Islam. The Mosque in America study, which described the structure and functioning of 416 mosques and the roles of the leaders of these mosques, found that 74 percent of the mosques provided marital and family counseling services directly to their congregants (17). However, it is not known if imams are well prepared to identify, treat, and, when necessary, refer congregants with emotional, behavioral, or psychosocial problems to psychiatric services.

We sought to elucidate the role of imams in meeting the counseling needs of their communities in the United States. In this article we summarize the imams' reports of the nature and extent of the counseling needs of their respective congregations and changes in these needs since September 11, 2001. We also report imams' current and past counseling experiences and training.

Methods

We conducted a nationwide cross-sectional survey of imams from mosques throughout the United States by using the directory in The North American Muslim Resource Guide, which contains the addresses of 1,118 mosques (3).

In February 2003 we mailed 450 questionnaires to imams of mosques that were randomly selected from the guide. In April 2003, because we began receiving more undeliverable questionnaires than completed ones, we mailed another 314 questionnaires, this time using only the remaining addresses that also were listed in the Verizon Superpages' online directory. A total of 730 questionnaires were not returned as undeliverable.

Each mailing was written in English and included a cover letter addressed to the imam that described the study and assured anonymity, an endorsement letter from an imam of a large Midwestern community, a stamped self-addressed envelope, and a 79-item questionnaire, which was developed by the authors and adapted from previous work (14). We sent reminder postcards to all the mosques one month after the first wave of mailings and did not provide any monetary incentives. The institutional review board of the Weill Medical College of Cornell University approved the research protocol and method of informed consent.

Results

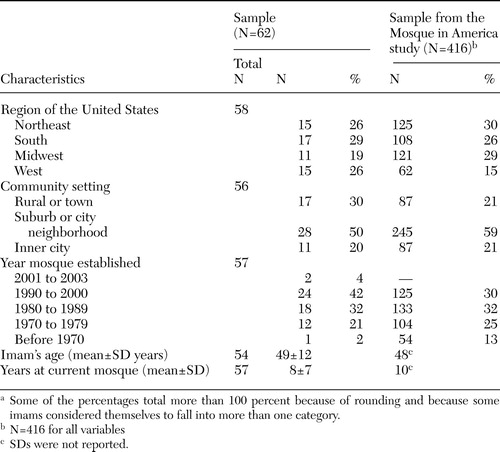

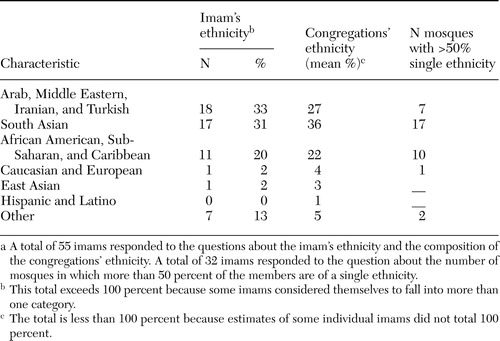

Sixty-two of 730 questionnaires were returned (return rate of 8 percent). Table 1 compares participants of this study with those in the Mosque in America study, which had a return rate of 66 percent. Gender was not asked because imams, by definition, are male. Ninety-one percent of imams (50 of 55 respondents who answered this question) reported that their mosques' Islamic affiliation was Sunni, and 53 percent (30 of 57 respondents) reported that their communities had more than 100 families. Table 2 summarizes the ethnicities of the imams, the ethnic composition of their communities, and the number of communities in which more than 50 percent of the members are of a single ethnicity.

No imams reported having a degree in psychiatry (0 of 55 respondents). Five percent reported having a degree in psychology (three of 55 respondents), 9 percent in social work (five of 55 respondents), and 7 percent in counseling (four of 55 respondents). Given a list of possible counseling training experiences, 13 percent (seven of 56 respondents) reported having had a formal clinical pastoral education, 21 percent (12 of 56 respondents) reported having taken a course on counseling given by an Islamic organization, and 25 percent (14 of 56 respondents) reported having consulted with or worked under the supervision of a mental health professional.

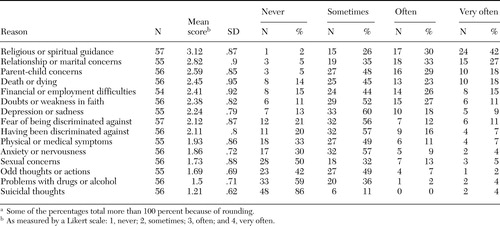

Fifty percent of imams (28 of 56 respondents) reported spending one to five hours each week in counseling activities, and 30 percent (17 of 56 respondents) reported spending six to ten hours each week. Five percent (three of 56 respondents) reported that they did not spend any time counseling. The proportion of the imam's workweek spent in counseling activities ranged from 0 to 80 percent, with a mean±SD of 17±17 percent. As shown in Table 3, the two most frequently reported reasons for which congregants sought counseling "very often" were religious or spiritual guidance (24 of 57 respondents, or 42 percent) and relationship or marital concerns (15 of 55 respondents, or 27 percent).

There were four concerns for which a majority of imams reported an increase in congregants' need for counseling after September 11, 2001: 68 percent (36 of 53 respondents) saw an increase in need for counseling for fears of discrimination, 62 percent (33 of 53 respondents) for actual discrimination, 62 percent (32 of 52 respondents) for financial concerns, and 51 percent (27 of 53 respondents) for anxiety. Imams' reports of increased need to counsel for actual discrimination since September 11, 2001, differed according to their mosques' ethnic majority: 100 percent of imams (seven of seven respondents) with congregations in which a majority are Arab American, 60 percent of imams (nine of 15 respondents) with congregations in which a majority are South Asian American, and 50 percent of imams (five of ten respondents) with congregations in which a majority are African American.

Discussion

Our principal finding is that imams are asked to address counseling issues in their communities that reach beyond religious and spiritual concerns and include family problems, social needs, and psychiatric symptoms. We also found that there has been an increase in the need for counseling for issues of discrimination since September 11, 2001, particularly in Arab-American communities. To our knowledge this study is the first to describe and quantify the multiple mental health counseling roles of Muslim clergy across the United States.

Imams are less likely than other clergy to have formal comprehensive counseling training that might help them to effectively address their communities' multidimensional needs. The ethnic diversity of Muslim communities suggests the need for mental health professionals who have particular sensitivity to congregants' individual cultural and religious backgrounds.

The rate of return of 8 percent raises a number of considerations. Many mosques may not have had an appropriate individual to complete the survey, because 19 percent of mosques do not have imams (17). The comprehensive questionnaire—which included 79-items, a vignette, multiple Likert scales, and open-ended questions—may have been a barrier to imams whose primary language is not English and to imams who are overburdened with obligations. Other imams may have thought that a survey about mental health issues was not relevant to their role as a religious leader.

The sociopolitical climate in the United States also could have been a significant factor in lowering the response rate. During the time that we conducted our survey, the United States had embarked on a war against a Muslim country, Iraq, and the government had enhanced its surveillance of imams' sermons and mosques' activities. Some imams expressed their concern about our intentions for conducting this survey. Such concern may have also reduced our return rate.

Despite the low return rate of this anonymous survey, it elicited responses from a group of imams who are ethnically, professionally, and religiously diverse and who lead a variety of Muslim congregations throughout the United States, similar to the larger Mosque in America study, which was conducted before September 11, 2001.

Conclusions

Further studies are required to confirm our results and to describe the degree to which imams use community mental health resources. Also, future surveys to comprehensively assess needs should elicit the perspectives of Muslim congregants, especially women and persons who come from different cultures than their imams, to ascertain if their counseling needs are being met. We recognize the need to foster communication and trust between Muslim religious leaders and mental health professionals to improve access to religiously and culturally appropriate psychiatric services. As mental health professionals have done with other clergy (15,18), they could collaborate with imams through outreach services to help fulfill a potentially vital role in improving access to appropriate mental health and social services for minority Muslim communities where there currently appear to be unmet psychosocial needs.

Acknowledgments

Funding and resources were provided by the Payne Whitney Clinic psychiatry residency training program of the department of psychiatry at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Medical College of Cornell University. Dr. Milstein's work was supported by a grant from the social sciences division of The City College of The City University of New York.

Dr. Ali is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital, New York University Medical Center, 462 First Avenue, 20 West 1, New York, New York 10016 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Milstein is with the department of psychology at The City College of The City University of New York in New York City. Dr. Marzuk is with the department of psychiatry at Weill Medical College of Cornell University in New York City.

|

Table 1. Comparison of demographic characteristics of imams from study sample with imams from the sample from the Mosque in America studya

a Some of the percentages total more than 100 percent because of rounding and because some imams considered themselves to fall into more than one category.

|

Table 2. Ethnicities of imams and their congregationsa

a A total of 55 imams responded to the questions about the imam's ethnicity and the composition of the congregations' ethnicity. A total of 32 imams responded to the question about the number of mosques in which more than 50 percent of the members are of a single ethnicity.

|

Table 3. Reasons for which congregants currently come to imams for counselinga

a Some of the percentages total more than 100 percent because of rounding.

1. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, 1999Google Scholar

2. Mental Health Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2001Google Scholar

3. Nimer M: The North American Muslim Resource Guide: Muslim Community Life in the United States and Canada. New York, Routledge, 2002Google Scholar

4. Christie-Smith D, von Brook P: Highlights of the 2001 Institute on Psychiatric Services. Psychiatric Services 53:32–36, 2002Link, Google Scholar

5. Veroff J, Kulka R, Douvan E: Mental Health in America: Patterns of Help-Seeking from 1957–1976. New York, Basic Books, 1981Google Scholar

6. Larson DB, Hohmann AA, Kessler LG, et al: The couch and the cloth: the need for linkage. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:1064–1069, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Piedmont EB: Referrals and reciprocity: psychiatrists, general practitioners, and clergymen. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 9:29–41, 1968Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Schindler F, Berren MR, Hannah MT, et al: How the public perceives psychiatrists, psychologists, nonpsychiatric physicians, and members of the clergy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 18:371–376, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Young JL, Griffith EEH, Williams DR: The integral role of pastoral counseling by African-American clergy in community mental health. Psychiatric Services 54:688–692, 2003Link, Google Scholar

10. Wang PS, Berglund PA, Kessler RC: Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Services Research 38:647–673, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Domino G: Clergy's knowledge of psychopathology. Journal of Psychology and Theology 18:32–39, 1990Google Scholar

12. Weaver AJ: Has there been a failure to prepare and support parish-based clergy in their role as frontline community mental health workers? A review. Journal of Pastoral Care 49:129–147, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

13. Weaver AJ, Koenig HG, Ochberg FM: Posttraumatic stress, mental health professionals, and the clergy: a need for collaboration, training, and research. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9:847–855, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Milstein G, Midlarsky E, Link BG, et al: Assessing problems with religious content: a comparison of rabbis and psychologists. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:608–615, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. McMinn MR, Aikins DC, Lish RA: Basic and advanced competence in collaborating with clergy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 34:197–202, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Haddad YY, Lummis AT: Islamic Values in the United States: A Comparative Study. New York, Oxford University Press, 1987Google Scholar

17. Bagby I, Perl P, Foehle B: The Mosque in America: A National Portrait: A Report From the Mosque Study Project. Washington, DC, Council on American-Islamic Relations, 2001Google Scholar

18. Milstein G: Clergy and psychiatrists: opportunities for expert dialogue. Psychiatric Times 20:36–39, 2003Google Scholar