Economic Grand Rounds: Patients' and Caregivers' Willingness to Pay for a Cure for Schizophrenia in Taiwan

Two main approaches are used to assign a monetary value to health and quality of life. The first is the human capital approach, and the second is willingness to pay, or the contingent valuation method (1). The human capital approach measures the value of a person's life by his or her potential labor production. Because of the way this method assigns value, it may not place as much value on the lost productivity of persons who are elderly, unemployed, or children (2). No explicit value is placed on intangible costs, such as pain and suffering associated with illness or deterioration of quality of life. Therefore, this approach may be inappropriate when estimating the economic effects of an illness like schizophrenia.

The contingent valuation method places a value on life according to how much an individual is willing to pay to reduce the probability of illness or death. This approach measures the value that patients place on improving their health or preventing further deterioration of their health (3). Also, the contingent valuation method allows a consumer to evaluate treatment benefits from an individual perspective. Use of this approach may provide further insight into the effect that schizophrenia has on human life.

This method has been used among patients with various diseases to measure how much they value improvement in their health. However, among patients with schizophrenia, contingent valuation has been used only to specifically estimate valuation and preferences of health states related to the side effects of antipsychotic medications (4). This study used contingent valuation to determine how much persons with schizophrenia and their caregivers were willing to pay for a hypothetical new medication that would cure schizophrenia.

Methods

Patients were eligible for our study if they had been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code 295 and all its subgroups or A-code 211 for ambulance) between December 2000 and June 2001 at the day care center and the psychiatry outpatient clinic at Taipei Veterans General Hospital. After participants were given a complete explanation of the study, informed consent was obtained in writing. Caregivers who accompanied patients or who came to pick up patients' medication were also interviewed. Our study was approved by the hospital's human subjects committee.

Patients were asked various questions about demographic characteristics. Caregivers were asked the same questions. Patients were also asked about past and current employment and illness history. Patients were also asked how much money they would be willing to pay out of pocket each month for a hypothetical new, cutting-edge medication that did not have any side effects and would allow them to have a symptom-free, normal life. Two scenarios were presented. The first stated that the medication would have to be taken for the remainder of the patient's life. The second, that the medication would have to be taken for only one year, after which time the disease would be cured. Caregivers were asked the same questions. An open-ended format was used. Respondents were directly asked how much they were willing to pay. We described the side effects and limits of all antipsychotics presently available. We explained that it was highly unlikely that the government would pay for an expensive new medication—they would have to pay for it themselves. We reminded them that by spending money on the medicine, the money could not be spent on other things.

At the time this study was performed the exchange rate was New Taiwan (NT) $31.4 for U.S. $1. Except for where noted, results are given in U.S. dollars.

Results

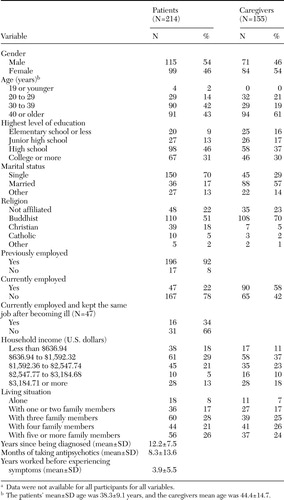

In total, 214 patients and 155 caregivers completed the interview. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the population studied.

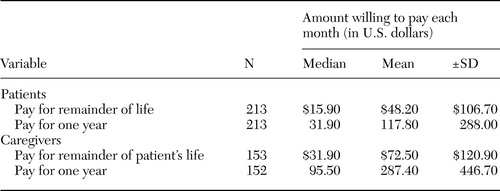

Table 2 shows that if patients needed to take the hypothetical medication for the rest of their lives, they were willing to pay a mean of $48.20 each month. If patients needed to take the medication for only one year, they were willing to pay a mean of $117.80 each month. If the medication needed to be taken for the remainder of the patient's life, caregivers were willing to pay a mean of $72.50 each month. For only one year, they were ready to pay a mean of $287.40 each month. No significant differences were found between genders for either group (data not shown).

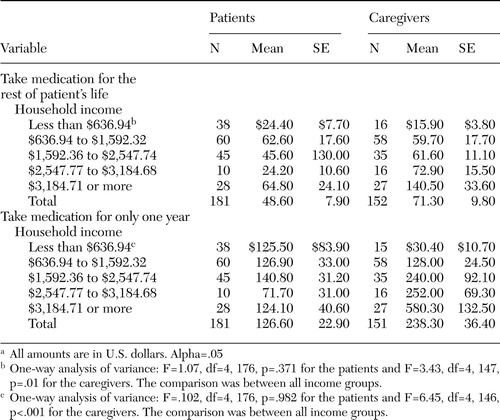

Table 3 illustrates the one-way ANOVA tests of the willingness to pay in different income groups. The results show no significant differences between household income and patients' willingness to pay. A significant difference was seen between household income and caregivers' willingness to pay in both the one-year and lifetime scenarios. Caregivers with higher incomes were willing to pay more. Caregivers who had a monthly income of $636.90 or less (NT $20,000 or less) were willing to pay a mean of $15.90 each month in the lifetime scenario. In this same situation, caregivers with the highest monthly income, $3,184.70 or more (NT $100,000 or more), were willing to pay a mean of $140.50 each month.

The scenario also affected caregivers' willingness to pay. In the one-year scenario, caregivers with a lower monthly income, $636.90 or less (NT $20,000 or less), were willing to pay a mean of $30.40 each month. Caregivers with the highest monthly income, $3,184.70 or more (NT $100,000 or more), were willing to pay a mean of $580.30 each month. Both patients and caregivers were willing to pay more each month in the one-year scenario.

Discussion and conclusions

This study used contingent valuation to estimate the value of medical care among patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan. We believed that this method was more comprehensive than the human capital method used in studies conducted in Taiwan and in other countries.

Our study found that 22 percent of the patients were still working. This finding is similar to those of Foster and colleagues (5), McCreadie (6), and Davies and Drummond (7), whose studies showed that approximately 20 percent of people with psychosis were still gainfully employed. Our study also found that only 34 percent of patients kept the same job after they became ill.

A significant correlation was found between household income and how much caregivers were willing to pay for the hypothetical new medication. However, there was no relationship between household income and patients' willingness to pay. This result can be explained if it is taken into consideration that patients may not have contributed much to the household income. Most patients had lost their jobs or did not enter the job market after their diagnosis. Although some patients received low subsidies from government welfare, the subsidies did not cover their living expenses, so they had to rely on their families. We suspect the ability-to-pay effect is only valid for people with a certain level of income. For those who do not have enough to provide a minimum standard of living, ability to pay is of no concern. Another explanation for the lack of a correlation between income and patients' willingness to pay is that the patients may have had cognitive problems, which would make contingent valuation an inappropriate method.

Both the patients and the caregivers were willing to pay more if the patient needed to take the medication for a shorter time (scope effect). The theory that willingness to pay is associated with income and scope effect has been tested in most contingent valuation studies (8). Our results showed theoretical validity in the caregiver group. However, this theory applied only partially to the patients.

All participants came from the same hospital. Thus the findings may not be applicable to all of Taiwan.

Contingent valuation is a new approach that can be used to measure how much patients with schizophrenia and their families are willing to pay for a hypothetical new medication that promises a cure. More research is needed to determine whether it is appropriate to apply this type of contingent valuation method in measuring quality of life among schizophrenia patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant NSC-89-2314-B-010-060 from the Taiwan National Science Council. The authors thank Tung-Pine Su, M.D., Hong-Shiow Yeh, M.D., and Chen-Jee Hong, M.D., for their assistance during the data collection period.

Dr. Lang is associate professor at the School of Medicine at National Yang-Ming University, Taiwan. Currently she is a scholar for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality at the University of California, Berkeley, 140 Warren Hall, MC 7360, Berkeley, California 94720 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., and Haiden A. Huskamp, Ph.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of a sample of patients with schizophrenia and caregiversin Taiwana

a Data were not available for all participants for all variables.

|

Table 2. Willingness of a sample of patients with schizophrenia and caregivers in Taiwan to pay for a hypothetical new medication that would cure schizophrenia

|

Table 3. Mean amount a sample of patients with schizophrenia and caregivers in Taiwanwere willing to pay each month for a hypothetical new medication that would cureschizophrenia, by household incomea

a All amounts are in U.S. dollars. Alpha=.05

1. Klose T: The contingent valuation method in health care. Health Policy 47:97–123, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Rice DP, Cooper BS: The economic value of human life. American Journal of Public Health 57:1954–1966, 1967Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Mitchell RC, Carson RT: Using Survey to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method. Washington DC, Resources for the Future, 1993Google Scholar

4. Sevy S, Nathanson K, Schechter C, et al: Contingency valuation and preferences of health states associated with side effects of antipsychotic medications in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:643–652, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Foster K, Gill H, Hill B, et al: OPCS Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity in Great Britain Report 8: Adults With a Psychotic Disorder Living in the Community. London, Department of Health, Scottish Home and Health Department, Welsh Office, 1996Google Scholar

6. McCreadie RG: The Nithsdale schizophrenia surveys. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27:40–45, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Davies LM, Drummond MF: The economic burden of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Bulletin 14:522–525, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Diener A, O'Brien B, Gafni A: Health care contingent valuation studies: a review and classification of the literature. Health Economics 7:313–326, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar