A Simulated Workplace Experience for Nonmedicated Adults With and Without ADHD

Abstract

Eighteen nonmedicated adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and 18 who did not have ADHD were evaluated in a full-day simulated workplace experience. It was hypothesized that adults with ADHD would evidence greater impairments on simulated tasks, off-task behavior, and self-reported ADHD symptoms than those without ADHD. Participants were compared on self-reported ADHD symptoms, objective observations, and performance on written tasks. Significant differences were noted in reading comprehension and math fluency as well as observer-rated and self-reported behavior, but not attention. The results of this study suggest that ADHD among adults is associated with significant deficits in performance of workplace tasks, internal experiences, and external observations of core symptoms of ADHD.

It is estimated that at least 4 percent of adults in the United States have attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (1). Like its pediatric counterpart, ADHD among adults has been associated with high levels of functional impairment (2,3), so much so that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers ADHD to be a cost burden to our society (4).

Although one of the most burdensome aspects of ADHD among adults is its detrimental impact in the workplace, there is almost no information that systematically verifies the relationships of ADHD-related deficits and symptoms with workplace outcome. We sought to investigate workplace deficits among adults with ADHD by assessing performance during a full-day simulated workplace experience. The simulated tasks were based on the results of the Labor Secretary's Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills (SCANS) study, which established a comprehensive list of skills necessary for achieving success in the workplace, as determined by employers in the National Academy of Sciences (5). These skills include the ability to read, think critically, regulate performance, deal with unfamiliar or irregular occurrences, multitask, and work as a member of a team. The workplace laboratory that was used in our study simulates the multitasking environments described in all jobs, which in the Labor Secretary's report included construction workers, waitresses, teachers, and chief executive officers. The common themes in all these jobs were task shifting, interaction, and task completion. Many of these specific abilities appear to be at odds with the core symptoms of ADHD. We used instruments that targeted the skills outlined in the SCANS reports in this study.

For adults with ADHD, attaining a high occupational status is one of the most impaired areas of functioning (6). We hypothesized that nonmedicated adults with ADHD would evidence impairments on tasks, more off-task behaviors, and more self-reported symptoms of ADHD than matched control participants. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first assessment of simulated workplace performance among adults with ADHD.

Methods

Adults with and without ADHD were recruited in the fall of 2003. Participants were selected for the control group if they did not meet DSM-IV criteria for ADHD or had fewer than three ADHD symptoms. Individuals responded to a hospital advertisement and were screened at our office for ADHD symptoms. Participants with ADHD were recruited through clinical referrals to an adult ADHD program at a major medical center as well as advertisements in local media and were included if they met full DSM-IV criteria for ADHD. Participants were excluded if they had an IQ below 80, did not speak English, or had other DSM-IV diagnoses. Statistical comparisons between participants with and without ADHD showed no differences in IQ, gender, age, or socioeconomic status. The study was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants took part in an eight-hour workplace simulation, which included sitting at classroom-style tables and completing questionnaires and two of each of the following: reading, logic problems, writing, math fluency subtests, and comprehension of video presentations. These activities were conducted twice during the day in a prelunch and postlunch session. All the participants with ADHD who were being treated with stimulant medication were asked to abstain from taking their prescribed medications for 24 hours before their participation and throughout the study so that impairments associated with ADHD could be measured.

Participants were observed and rated by using the Swanson, Kotkin, Agler, M-Flynn, and Pelham (SKAMP) rating scale (7). The SKAMP was revised for this study to be more congruent with behaviors observed among adults in workplace settings (SKAMP-R) (8). Research assistants, who were blinded to each participant's ADHD status and who had extensive training in the SKAMP-R, used the instrument to rate 12 items representing two factors of classroom behavior: attention and behavior. Each item is rated on a scale of 0 to 6, with 0 indicating normal functioning and 6 indicating severe impairment (7). Participants were also asked to fill out a self-report questionnaire on subjective feelings of being overwhelmed, being bored, having trouble focusing, having trouble sitting still, and having difficulty keeping quiet. These self-reports were filled out after each task and reflected participants' experiences with the specific task.

Continuous data were analyzed with t tests, and categorical data were analyzed with Pearson's chi square tests. To examine rating profiles over the course of the day, generalized estimating equations were used to account for repeated measures. Group status by task ordering interactions were used to determine whether the profiles of ratings were different between participants with ADHD and those without ADHD as they progressed through the simulated workday. All statistical tests were two-sided; statistical significance was set at p<.05.

Results

Thirty-six participants took part in the study (18 with ADHD and 18 matched control participants). Participants with ADHD met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD and had a higher lifetime risk of substance use disorders and lower Global Assessment of Functioning scores.

Compared with the control participants, the participants with ADHD demonstrated impaired performance in reading comprehension and math fluency. In contrast, performance on tasks that assessed problem solving (logic), comprehension of video presentations, and writing were not impaired among the participants with ADHD compared with the control participants.

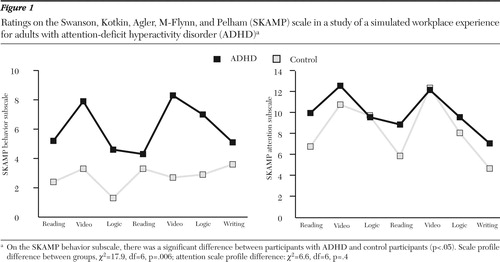

Overall, a statistically significant difference was noted in the profile of the SKAMP-R behavior subscale, but not the attention subscale. Despite lack of performance deficits on problem solving and video comprehension, participants with ADHD had significantly more impaired behavioral problems during these tasks. On the reading comprehension task completed in the morning, there was an observable impairment participants' ability to pay attention problems (Figure 1).

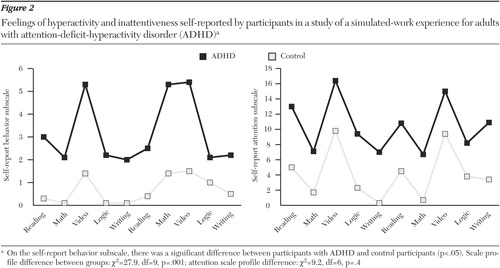

For subjective self-ratings of inattention and hyperactivity, the difference in the overall profiles of participants with and without ADHD was statistically significant for the behavior scale but not the attention scale (Figure 2). Participants with ADHD reported subjective difficulty with hyperactivity on all tasks completed, with the exception of the problem-solving task after lunch. Despite the lack of an overall difference in the profile of subjective feelings of difficulty maintaining attention, participants with ADHD rated themselves as more impaired during the reading comprehension, math fluency, and writing task than did participants without ADHD.

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to develop a simulated workplace experience to examine whether the dimensions documented by the U.S. Department of Labor for workplace success are impaired among persons with ADHD. The results showed that persons with ADHD had significant deficits in the simulated workplace compared with those who did not have ADHD. In addition, participants with ADHD exhibited a significantly higher number of core symptoms of ADHD, as observed by objective raters and as noted on self-reports.

The workplace deficits associated with ADHD documented in this study match very well with recently reported findings from a large survey of adults in the community who did and did not have ADHD, demonstrating the high impact of ADHD in the workplace (6). This survey showed that adults with ADHD are at a high risk of being unemployed or underemployed, are less frequently considered for promotion, and attain much lower wages and salaries.

The workplace deficits associated with ADHD documented in this study are particularly meaningful, because they correspond well with the SCANS report of skills needed for success in the workplace. The commission's fundamental purpose was to encourage a high-performance economy characterized by high-skill, high-wage employment. In this context, our findings show that individuals with a diagnosis of ADHD are at a high risk of being unsuccessful in the modern workplace.

One of the core competencies identified by the commission was an increase in the need for literacy by individuals at all levels of the workforce. Our study showed that persons with ADHD had more difficulty in comprehension and speed while reading. If replicated, these results suggest that reading skill deficits compound the already compromised occupational functioning of an adult who has ADHD. More work is needed to further evaluate this hypothesis and ascertain whether the effect of ADHD on workplace performance is realized only when it overlaps with other core deficits, such as reading comprehension difficulties (9).

Our study also documented significantly lower scores on a math fluency task among adults with ADHD. The math fluency subtest of the Woodcock Johnson Test of Achievement (10) does not test knowledge base in math but, rather, the automaticity of simple math facts.

Our objective raters documented statistically significant differences between the study participants with ADHD and those without ADHD in terms of behavior on four of the seven tasks. In their self-reports, participants with ADHD reported difficulty keeping quiet and sitting still at a significantly higher rate than the other participants on nine of the ten periods of the day. Deficits in the area of inhibition can have a major impact in the work environment, because many of the behaviors noted could keep coworkers from performing at their optimal level, especially in light of the SCANS report, which states that more of today's jobs require cooperative work in teams. SKAMP measures of inattention included items that adults have compensated for. For example, getting started on a task, sticking to a task, and attending to an activity would all be things that would not be apparent to the objective rater. Thus participants were not necessarily attentive; rather, their inattentiveness was masked.

Our findings should be viewed in light of some methodologic limitations. More analysis is needed to better understand the question of learning disabilities among our participants. In addition, further study of the employment history of the participants with ADHD, as related to comorbid conditions, especially substance abuse, will be a critical area. Because the study participants were largely middle class and Caucasian, our findings may not generalize to other socioeconomic groups or ethnic minority groups.

Conclusions

This study pioneered the use of a simulated workplace experience for adults with ADHD. These findings are consistent with reports from individuals who have ADHD and from employers that the work performance of adults with ADHD is impaired, providing further support for the morbidity and dysfunction associated with this disorder during adulthood. Whether these workplace deficits improve with treatment remains to be investigated. Considering the fundamental importance of normalizing workplace deficits for adequate societal functioning, future research could benefit from specifically testing workplace performance in treatment studies of adults with ADHD.

The authors are affiliated with the pediatric psychopharmacology unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, ACC 7, Boston, Massachusetts 02114 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Ratings on the Swanson, Kotkin, Agler, M-Flynn, and Pelham (SKAMP) scale in a study of a simulated workplace experience for adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)a

a On the SKAMP behavior subscale, there was a significant difference between participants with ADHD and control participants (p<.05). Scale profile difference between groups, χ2=17.9, df=6, p=.006; attention scale profile difference: χ2=6.6, df=6, p=.4

Figure 2. Feelings of hyperactivity and inattentiveness self-reported by participants in a study of a simulated-work experience for adults with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)a

a On the self-report behavior subscale, there was a significant difference between participants with ADHD and control participants (p<.05). Scale profile difference between groups: χ2=27.9, df=9, p=.001; attention scale profile difference: χ2=9.2, df=6, p=.4

1. Kessler RC: Prevalence of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R). Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 1 to 6, 2004Google Scholar

2. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux M, et al: Gender effects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults, revisited. Biological Psychiatry 55:692–700,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Weiss M, Hechtman L, Weiss G: ADHD in Adulthood: A Guide to Current Theory, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 1999Google Scholar

4. Hinshaw SP, Peele P, Danielson L: Public Health Issues in ADHD: Individual, System, and Cost Burden of the Disorder. Workshop. Atlanta, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, 1999Google Scholar

5. Wise L, Chia W, Rudner L: American Institutes for Research: The Secretary's Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills. Washington, DC, Pelavin Associates, 1990Google Scholar

6. Faraone SV, Biederman J: A controlled study of functional impairments in 500 ADHD adults. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 1 to 6, 2004Google Scholar

7. Wigal S, Gupta S, Guinta D, et al: Reliability and validity of the SKAMP rating scale in a laboratory school setting. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 34:47–53,1998Medline, Google Scholar

8. Rochon J: Application of GEE procedures for sample size calculations in repeated measures experiments. Statistics for Medicine 17:1643–1658,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Nadeau KG: A Comprehensive Guide to Attention Deficit Disorder in Adults: Research, Diagnosis, Treatment. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1995Google Scholar

10. Woodcock RW, McGrew K, Mather N: Woodcock Johnson Tests of Achievement-3rd Edition. Itasca, Ill, Riverside, 2001Google Scholar