Racial Differences in Syndromal and Subsyndromal Depression in an Older Urban Population

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors explored racial differences in the prevalence of depression and its associated factors among older persons. METHODS: Using 1990 census data for Brooklyn, New York, the authors attempted to interview all cognitively intact persons age 55 years and older in randomly selected block groups. The sample was weighted by ethnicity and gender. The authors adapted George's Social Antecedent Model of Depression to allow examination of 20 independent variables and the nominal dependent variable consisting of three levels of depression. The data were analyzed with SUDAAN. RESULTS: Syndromal depression was found among 8 percent of blacks and 10 percent of whites. Subsyndromal depression was found among 13 percent of blacks and 28 percent of whites. No racial differences were found in rates of syndromal depression, but significant racial differences were found in rates of subsyndromal depression and of any type of depression. Nonlinear effects on both types of depression were found, and higher levels of stress had a greater impact on whites than on blacks. The racial difference in subsyndromal depression was explained by its lower prevalence among French-speaking African Caribbeans. Many racial differences were found in the variables associated with syndromal and subsyndromal depression. CONCLUSIONS: Race had an independent effect on the rate of subsyndromal depression and an interactive effect with stress on the rate of both syndromal and subsyndromal depression. For each racial group, different elements may play a role in the etiology, maintenance, and relief of depression. The findings underscore the importance of recognizing within-group and between-group racial differences in depression.

In 2003, the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance Consensus Development Panel on mood disorders in late life recommended more study of various levels of depression in underserved minority groups (1). Only a few population-based studies have included large numbers (more than 200) of older African Americans (2,3,4,5), and northern metropolitan areas have been neglected, despite their having a disproportionately large number of older black residents compared with other sections of the United States (6). Moreover, the black populations in these areas have become more diverse, with the influx of approximately 2 million African Caribbean immigrants into the United States during the 1980s and 1990s (7). Among earlier studies, research in Nashville (4), research in Florida (5), and the Duke Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (EPESE) study (2) were conducted in the south, and the latter had many rural participants. Although the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study (3) included diverse geographic sites, it was undertaken more than 20 years ago, and consequently the results do not reflect more recent changes in the composition of the older black urban population.

The findings on racial differences in depression have been inconsistent. The Duke EPESE and the overall ECA study did not find significant racial differences in rates of syndromal depression among older adults (2,3,8), although significantly higher rates of dysthymia among whites and a trend toward higher rates of major depression among whites were found in the North Carolina ECA site (9). The Nashville study showed significantly greater depressive symptom scores among whites at baseline but higher scores among blacks at an 18-month follow-up (4). The Florida study showed no significant racial differences in depression symptom scores (5).

Previous studies were limited by the lack of a theoretical model for assessment of depression. Use of a theoretical model allows for the rational inclusion of an array of predictor variables and provides a basis for generalization across studies. For this study, we used an adaptation of George's Social Antecedent Model of Depression (10), which consists of six stages of risk factors—demographic factors, early and later events and achievements, social integration and support, vulnerability factors, provoking agents, and coping strategies. George's model is consistent with Krishnan's biopsychosocial model of depression (11), in which it is proposed that various physical disorders and genetic predisposition contribute to an individual's vulnerability to depression, which is in turn modulated by life events and social support.

Another limitation of aging research noted by the Consensus Development Panel was the lack of studies of racial differences in various levels of depression severity (1). Both syndromal and subsyndromal depression have been found to be associated with impaired functioning, disability, medical illness, and mortality (12,13). To examine racial differences in these levels of depression severity, we used George's theoretical model to examine the prevalence of and factors associated with depression in a large multiracial population of New York City residents aged 55 years and older. We addressed the following two questions: Does the prevalence of syndromal and subsyndromal depression differ by race? Do blacks and whites differ in the factors that are associated with the different levels of depression severity?

Methods

Sample

Using the Wessex Corporation's 1990 census STF3 files for Kings County, New York (Brooklyn), we identified black and white persons aged 55 years and older. We randomly selected block groups without replacement as the primary sampling unit. For each block group, we estimated the approximate populations by ethnicity and gender by using sampling weights computed as the reciprocal of the selection probabilities for each observation. Our study design called for interviewing a minimum of 200 persons in each of four ethnic groups: Caucasians, African Americans born in the United States, African Caribbeans from islands where English is spoken, and African Caribbeans from islands where French and Creole are spoken. Data collection took place from 1996 to 1999.

We attempted to interview all eligible persons in a selected block group by contacting potential study participants at their home address. Only one person per household could be interviewed. Because some persons were reluctant to open their doors, we attempted to enhance response rates by contacting participants in the selected block groups at senior centers and churches and through personal references. Thirty percent of the sample was recruited through these means. The overall response rate was 77 percent of the persons who were contacted. We administered the Mental Status Questionnaire (14) to exclude persons with moderate to severe cognitive impairment (that is, those with a score of 4 or less) (15). The final community sample consisted of 214 Caucasians and 860 blacks, of whom 34 percent, 35 percent, and 31 percent were born in the United States, the English Caribbean, and the French Caribbean, respectively. All the French African Caribbean participants were from Haiti. The weighted total populations of Kings County by race, based on 1990 census, were 122,988 blacks and 317,629 Caucasians. The weighted total populations of Kings County by gender were 175,120 males and 265,496 females.

After providing a description of the study to the participants, we obtained written informed consent. The institutional review board of the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center approved this study.

Instruments and variables

Previous research has suggested that depression in later life may be associated with physical illness, poor subjective health status, cognitive deficits, impaired vision or hearing, functional limitations, life stressors, diminished social support, bereavement or loss of important persons, coping strategies, beliefs and attitudes about mental illness, lower income, use of psychotropic medications and psychiatric treatment, older age, gender (female), race (black), lower educational level, being unmarried, and immigrant status (5,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26). The adaptation of George's model was used to incorporate the relevant variables into the study design.

We operationalized 20 independent variables and a dependent variable consisting of three levels of depression (syndromal depression, subsyndromal depression, and no depression) (Table 1). The independent variables were derived from several sources. A physical illness score was calculated from the sum of scores for 29 physical health items from the Multilevel Assessment Inventory; lower scores indicate worse health (27). A functional impairment score was derived from the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Physical Self-Maintenance Scale (27); lower scores indicate more impairment. Financial strain was measured with the Financial Strain Scale (28), on which lower scores denote more strain. Coping strategies were assessed with a 23-item coping scale derived from items suggested by Pearlin and colleagues (29). Principal components analysis with Varimax rotation was used to generate five subscales consisting of acceptance of the situation, finding meaning in the situation, use of distraction, use of social contacts, and use of medications or health care professionals. In this study we used the score of the acceptance subscale as a measure of coping strategy.

The Trauma and Victimization Scale (30) was used to determine a lifetime trauma score reflecting whether the respondent had experienced 18 lifetime traumatic events, including physical abuse, sexual assault, physical assault, and witnessing of violence. The Acute Stressors Scale (31) was used to determine an acute stressor score reflecting whether 11 stressful life events had occurred in the past month. The Network Analysis Profile (32) was used to measure variables concerning network size and intimacy.

We developed a 93-item Mental Health Beliefs Scale on the basis of data from community focus groups. Principal components analysis with Varimax rotation was used to derive six subscales to measure respondents' beliefs about the causes and cure of mental illness in the areas of spirituality, religion, stress, family heredity and rearing effects, environmental effects, and empathy and understanding. In this study we used the score on the religion subscale to measure respondents' beliefs about the role of religious activities in ameliorating mental illness. Belief in spiritualism was rated as present if the respondent saw a spiritualist or purchased items from a religious shop. Internal consistency, measured with Cronbach's alpha, was .72 for the functional impairment score, .88 for the Financial Strain Scale score, .57 for the coping acceptance score, .68 for the Trauma and Victimization Scale score, .77 for the Acute Stressors Scale score, and .84 for the Mental Health Beliefs Scale religion subscale. All scales had alphas that were above the acceptable level of .60 (33), except for the three-item coping scale, which fell slightly below this level.

The dependent variable, which reflected three levels of depression, was derived from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (34). Syndromal depression was indicated by scores at or above the customary CES-D cutoff score of 16, which has been shown to correlate with clinically significant depression (19,35). We selected CES-D scores ranging from 8 to 15 to indicate subsyndromal depression. Researchers lack consensus regarding the characteristics of subsyndromal depression, which is sometimes called "subthreshold" or "subcase" depression. However, persons with subsyndromal depression are recognized to be at risk of functional impairment and disability (12). Typically, the presence of two or more symptoms of depression is required for identification of subsyndromal depression (36).

We used more conservative criteria for subsyndromal depression. To qualify for this category, respondents in our study were required to indicate that at least three symptoms on the 20-item CES-D scale were present a "good part or most of time," resulting in a CES-D score of at least 8. Among persons who met the criteria for subsyndromal depression in this study, the mean±SD number of CES-D symptoms was 8.2±2.1. In contrast, for persons in the syndromal depression group, the mean number of CES-D symptoms was 13.6±2.5. Respondents who had a CES-D score of less than 8 were considered nondepressed. The mean number of CES-D symptoms in this group was 1.4±2.1.

For Haitian respondents, the study questionnaire was translated into Creole and then back-translated, according to the methods described by Flaherty and colleagues (37). Interviewers were trained with audio- and videotapes and were generally matched to respondents from similar ethnic backgrounds. Interrater reliability, as measured by intraclass correlation, ranged from .86 to 1.0 for the scales used with this sample. The interviewers were periodically monitored with audiotapes.

Data analysis

To control for intra-block clustering effects and for the effect of sampling without replacement, the data analysis was performed with Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN) 7.5.4A (38). The unit of analysis was the individual. All analyses were conducted by using sampling weights. For measures that generated more than one independent variable, we conducted preliminary bivariate analyses and selected one or more variables from that measure that had substantial association (p<.10) with the dependent variable (preliminary analyses not shown). For the final analyses, we included four demographic variables—gender, age, race, and education. In addition, ethnicity, or place of birth, was used as a variable in analyses of data for black respondents. We found no evidence of collinearity among the selected variables. To determine which interaction variables to include, we minimized collinearity by excluding interactions in which the correlation between the interaction variable and its component variables was greater than .80. Despite various transformations, only one interaction variable—the interaction of race (white) and acute stressor score—met this criterion. Generalized multinominal regression analysis was used to estimate the odds that syndromal or subsyndromal depression, compared with no depression, was associated with each of the independent variables.

Results

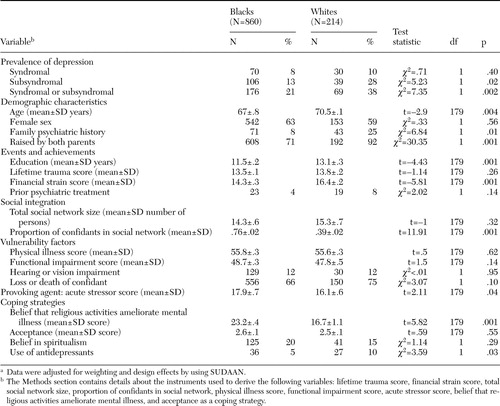

After weighting and adjustment of the data for the effects of the study design, we found that 33 percent of the sample met the criteria for syndromal or subsyndromal depression. In bivariate analyses, a significant racial difference was found in the prevalence of subsyndromal depression but not syndromal depression (Table 1). The rates of syndromal depression among older blacks and whites were 8 percent and 10 percent, respectively, and the rates of subsyndromal depression were 13 percent and 28 percent, respectively. Overall, 38 percent of older whites, compared with 21 percent of older blacks, had either syndromal or subsyndromal depression, a statistically significant difference. As Table 1 shows, significant racial differences were found for nine variables in the model.

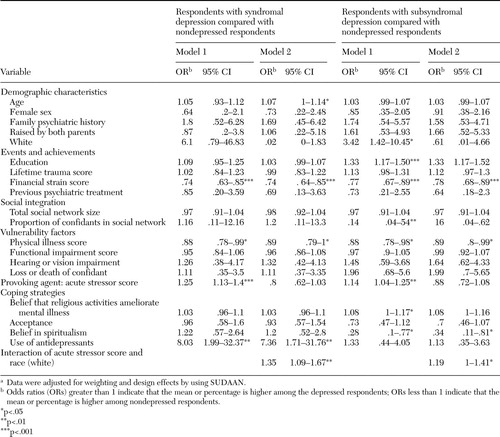

The 20 independent variables were entered into a multinominal regression analysis (model 1). As Table 2 shows, the racial difference in syndromal depression remained nonsignificant, and the racial difference in subsyndromal depression continued to be significant in this analysis. Moreover, the racial difference in any type of depression remained significant (odds ratio=4.15, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.29-13.35, p=.02). The interaction of race (white) and acute stressor score was added to the regression analysis in model 2. The interaction was significantly associated with both syndromal and subsyndromal depression. However, the difference in subsyndromal depression associated with race alone was no longer significant in model 2. In model 2, four other variables besides the interaction of race and acute stressor score were significantly associated with syndromal depression. They were older age, worse physical health, greater financial strain, and greater likelihood of using antidepressants. Also in model 2, four other variables besides the interaction were significantly associated with subsyndromal depression. They were higher educational level, lower likelihood of belief in spiritualism, worse physical health, and greater financial strain. The belief that religious activities help alleviate mental illness had a marginally significant association with subsyndromal depression in model 2 (p=.056).

A subanalysis in which blacks born in the United States were compared with whites indicated no significant racial differences in the prevalence of either type of depression or in the effect of the interaction variable (syndromal depression: no effect of race [β=-2.61, t=-.86, df=179, p=.39] and no effect of the interaction of race [white] and acute stressor score [β=.21, t=1.37, df=179, p=.17]; subsyndromal depression: no effect of race [β=-2.42, t=-.91, df=179, p=.37] and no effect of the interaction of race [white] and acute stressor score [β=.13, t=.81, df=179, p=.42]).

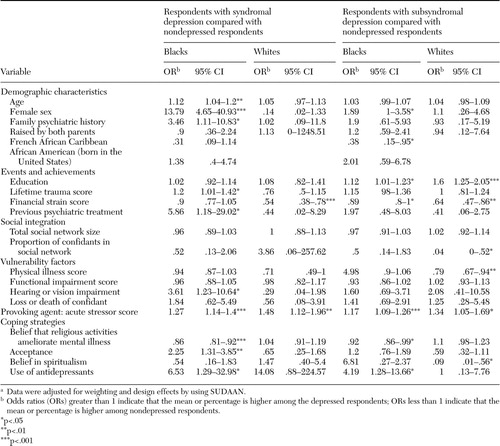

To determine which factors were associated with the two categories of depression within each racial group, all the variables were entered into a multinominal regression analysis (Table 3). Ten variables were significantly associated with syndromal depression among older blacks: older age, female sex, family psychiatric history, higher lifetime traumatic events score, past psychiatric treatment, greater likelihood of hearing or vision impairment, higher acute stressor score, weaker belief that religion can help mental illness, higher score for acceptance as a coping strategy, and higher likelihood of using antidepressants. Seven variables were significantly associated with subsyndromal depression among older blacks: female sex, not being French African Caribbean, higher level of education, greater financial strain, higher acute stressor score, weaker belief that religion can help mental illness, and higher likelihood of using antidepressants. Among older whites, only two variables—greater financial strain and higher acute stressor score—were significantly associated with syndromal depression. Six variables were associated with subsyndromal depression among older whites: higher level of education, greater financial strain, lower proportion of confidants in the social network, worse physical health, higher acute stressor score, and lower level of belief in spiritualism.

Discussion

This study illustrates the importance of examining racial differences in various levels of depression severity as well as the importance of recognizing ethnic diversity among urban black elders. Unlike the researchers in the Duke EPESE study (8)—the only other study to examine racial differences in various levels of depression severity—we found significant racial differences in subsyndromal depression in both bivariate and multivariate analyses. Older whites had a significantly greater prevalence of subsyndromal depression than older blacks. This finding is noteworthy because subsyndromal depression is associated with higher levels of morbidity and mortality (12,13). Ethnic differences in subsyndromal depression within the black sample helped explain the difference in prevalence between blacks and whites. Blacks born in the United States or English African Caribbean countries had significantly higher levels of subsyndromal depression than French African Caribbeans. If, like other researchers, we had included only data for U.S.-born blacks in the analysis, no racial differences in subsyndromal depression would have been uncovered.

Why did French African Caribbeans (Haitians) have lower rates of depression, independent of other variables? Bibb and Casimir (39) observed that denial and stoicism are found commonly among Haitians, and these qualities make the diagnosis of depression more difficult to elicit. However, it is possible that they are truly less depressed than U.S.-born blacks and English African Caribbeans. For example, on the CES-D, French African Caribbeans reported being more "hopeful about the future" than other blacks (t=2.41, df=123, p=.02).

Graphing of the nonlinear effects of race and stressors on depression indicated that for both whites and blacks, the prevalence of syndromal and subsyndromal depression increased as stress increased. However, the probability of depression increased more rapidly among whites than among blacks. Thus black persons were more likely to show syndromal or subsyndromal depression at lower levels of stress, and whites were more likely to do so at higher levels of stress. Although both racial groups were affected adversely by increasing stress, older blacks may be better able to cope with higher levels of stress than older whites. Alternatively, the reaction of older blacks to higher levels of stress may differ from that of older whites. Instead of manifesting depression in reaction to stress, older blacks may display other emotions or behaviors.

The separate analyses of the data for each racial group showed that different variables were associated with syndromal and subsyndromal depression among blacks and whites. Only three of the 20 variables that had been identified as important in the depression literature were found to be significantly associated with depression in both racial groups. The acute stressor score was associated with syndromal and subsyndromal depression in both racial groups, financial strain was associated with both categories of depression in whites and with subsyndromal depression in blacks, and educational level was associated with subsyndromal depression in both racial groups. Thus, although the racial differences in the prevalence of syndromal depression may be nonsignificant, our analyses showed that the factors associated with syndromal and subsyndromal depression differed substantially between races. These findings suggest that for each race, different variables may affect the etiology, maintenance, and amelioration of depression.

In our theoretical model, subsyndromal depression was associated with seven nonracial variables and syndromal depression was associated with four nonracial variables. Our findings that financial strain, physical illness, functional impairment, and relative lack of confidants were associated with depression were consistent with previous reports (2,17,18,21,23). However, our finding that a higher level of education was significantly associated with subsyndromal depression conflicted with previous findings that depression is associated with lower levels of education (5,8,18,21,25). A possible explanation for our finding is that outmigration of the middle-class population (40) left high concentrations of impoverished and poorly educated people in many sections of the geographic area covered in our study. For respondents with higher levels of education, remaining in these troubled neighborhoods may reflect personal circumstances that could contribute to depression, or, conversely, respondents with more education may experience more profound emotional effects if they remain in these neighborhoods (40).

Our findings were consistent with the Florida study's finding of the importance of race in health beliefs (5). For example, for both races combined, subsyndromally depressed persons adhered to more standard beliefs and practices. They believed more intensively that religious activities could help alleviate mental illness, but they were less likely to use the services of spiritualists or purchase their products. However, when the races were considered separately, blacks were significantly more likely than whites to believe that religion could help with mental illness (Table 1), and this belief had a significant association with both levels of depression among blacks but not among whites (Table 3).

Finally, with respect to the prevalence of geriatric depression, the 10 percent rate for syndromal depression was similar to the rate reported for the multiracial sample in the Duke EPESE study (9.1 percent) (8) but lower than the rates reported for predominantly white samples in the Bronx (16.9 percent) (18) and in Europe (16 to 50 percent) (19,25). However, the rate of 24 percent for subsyndromal depression greatly exceeded the rate of 9.9 percent reported in the Duke EPESE study (8), although more stringent criteria for subsyndromal depression were used in the latter study.

The findings reported here may have differed from those of other studies because we used a symptom checklist rather than formal diagnostic criteria to identify syndromal and subsyndromal depression, our study was conducted in the second poorest county in New York State, our analyses were weighted to reflect the overall population of older blacks and whites in Brooklyn and were corrected for potential sampling design effects such as clustering, and we used a more comprehensive model of depression that included 21 predictor variables that assessed linear and nonlinear effects.

Conclusions

Our study of racial differences in the prevalence of syndromal and subsyndromal depression and its associated factors suggested four findings. First, race (white) was an independent predictor of subsyndromal depression. Second, racial differences in the prevalence of subsyndromal depression were due primarily to lower prevalence among French African Caribbeans (Haitians). Third, nonlinear racial effects of stress were found for both syndromal and subsyndromal depression. Fourth, racial differences existed in several factors associated with both levels of depression.

Readers should exercise appropriate caution in interpreting the results, because this study was limited by the use of cross-sectional data. In addition, the study was based on a broad view of clinical depressive syndromes, some of the within-group racial analyses were based on small samples, and the study participants were drawn from only one urban area. Nevertheless, the findings underscore the importance of recognizing within-group and between-group racial differences in depression.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant RO1-MH-53453 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Cohen and Ms. Walcott-Brown are affiliated with the department of psychiatry, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, Box 1203, 450 Clarkson Avenue, Brooklyn, New York 11203 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Magai is with the department of psychology of Long Island University in Brooklyn. Dr. Yaffee is a consultant with the department of psychiatry at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center.

|

Table 1. Prevalence of syndromal and subsyndromal depression and associated features in older black and white respondents in a community sample of residents of Brooklyn, New Yorka

a Data were adjusted for weighting and design effects by using SUDAAN.

|

Table 2. Multinomial regression analysis of variables associated with syndromal and subsyndromal depression in older respondents in a community sample of residents of Brooklyn, New Yorka

a Data were adjusted for weighting and design effects by using SUDAAN.

|

Table 3. Multinomial regression analysis of variables associated with syndromal and subsyndromal depression in older black and white respondents in a community sample of residents of Brooklyn, New Yorka

a Data were adjusted for weighting and design effects by using SUDAAN.

1. Charney DS, Reynolds CF 3rd, Lewis L, et al: Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:664–672,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, et al: The association of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. Journal of Gerontology 46:M210-M215, 1991Google Scholar

3. Somervell PD, Leaf PJ, Weissman MM, et al: The prevalence of major depression in black and white adults in five United States communities. American Journal of Epidemiology 130:725–735,1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Husaini BA: Predictors of depression among the elderly: racial differences over time. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:48–58,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mills TL, Alea NL, Cheong JA: Differences in the indicators of depressive symptoms among a community sample of African-American and Caucasian older adults. Community Mental Health Journal 40:309–331,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. US Bureau of the Census: We the Americans: Blacks. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1993. Available at www.census.gov/apsd/wepeople/we-1.pdfGoogle Scholar

7. Pierre-Pierre G: West Indians adding clout to the ballot box. New York Times, Sept 6, 1993, pp 17,19Google Scholar

8. Hybels C, Blazer D, Pieper C: Toward a threshold for subthreshold depression: an analysis of correlates of depression by severity of symptoms using data from an elderly community survey. Gerontologist 41:357–365,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Blazer D, Hughes DC, George LK: The epidemiology of depression in an elderly community population. Gerontologist 27:281–287,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. George L: Social and economic factors in late life, in Diagnosis And Treatment of Depression in Late Life. Edited by Schneider LS, Reynolds CF III, Leibowitz BD, et al. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 131–153Google Scholar

11. Krishnan KR: Biological risk factors in late life depression. Biological Psychiatry 52:185–192,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Blazer DG: Depression in late life: review and commentary. Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 58:249–265,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lavretsky H, Kumar A: Clinically significant non-major depression: old concepts, new insights. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 10:239–255,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kahn RL, Goldfarb AI, Pollack M, et al: Brief objective measures for the determination of mental status in the aged. American Journal of Psychiatry 117:326–328,1960Link, Google Scholar

15. Zarit SH, Miller NE, Kahn RL: Brain functioning, intellectual impairment and education in the aged. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 26:58–67,1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Bruce ML: Psychosocial risk factors for depressive disorders in late life. Biological Psychiatry 52:175–184,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Cole MG, Bellavance F, Mansour A: Prognosis of depression in elderly community and primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1182–1189,1999Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Kennedy GJ, Kelman HR, Thomas C: Persistence and remission of depressive symptoms in late life. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:174–178,1991Link, Google Scholar

19. Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Smit JH, et al: Predicting the course of depression in the elderly: results from a community-based study in the Netherlands. Journal of Affective Disorders 34:41–49,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Prince MJ, Harwood RH, Thomas A, et al: A prospective population-based cohort study of the effects of disablement and social milieu on the onset and maintenance of late-life depression: the Gospel Oak Project VII. Psychological Medicine 28:337–350,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Kivela SL, Pahkala K, Laipala P: The one-year prognosis of dysthymic disorder and major depression in old age. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 6:81–87,1991Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Sharma VK, Copeland JRM, Dewey ME, et al: Outcome of the depressed elderly living in the community of Liverpool: a 5-year-follow-up. Psychological Medicine 28:1329–1337,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Devanand DP, Kim MK, Paykina N, et al: Adverse life events in elderly patients with major depression or dysthymic disorder and in healthy-control subjects. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 10:265–274,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Haynie DA, Berg S, Johansson B, et al: Symptoms of depression in the oldest old: a longitudinal study. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 56:P111-P118, 2001Google Scholar

25. Minicuci N, Maggi S, Pavan M, et al: Prevalence rate and correlates of depressive symptoms in older individuals: the Veneto Study. Journals of Gerontology, Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 57:M155-M161, 2002Google Scholar

26. Murrell SA, Himmelfarb S, Wright K: Prevalence of depression and its correlates in older adults. American Journal of Epidemiology 117:173–185,1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lawton MP, Moss M, Fulcomer M, et al: A research and service-oriented multilevel assessment instrument. Journal of Gerontology 37:91–99,1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Pearlin LJ, Lieberman MA, Mehaghan EG, et al: The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22:337–356,1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Strauss MA: Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family 41:75–88,1979Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Cohen CI, Ramirez M, Teresi J, et al: Predictors of becoming redomiciled among older homeless women. Gerontologist 37:67–74,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Chatters LM: Health disability and its consequences for subjective stress, in Aging in Black America. Edited by Jackson JS, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1993Google Scholar

32. Sokolovsky J, Cohen CI: Toward a resolution of methodological dilemmas in network mapping. Schizophrenia Bulletin 7:109–116,1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Nunally JC: Psychometric Theory. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1967Google Scholar

34. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385–401,1977Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Beekman A, Geerlings S, Deeg D, et al: The natural history of late-life depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:605–611,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, Hays RD, et al: Subthreshold depression and depressive disorder: clinical characteristics of general medical and mental health specialty outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1777–1784,1994Link, Google Scholar

37. Flaherty JA, Gaviria FM, Pathak D, et al: Developing instruments for cross-cultural psychiatric research. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders 176:257–263,1988Medline, Google Scholar

38. Research Triangle Institute: SUDAAN: Software for Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data (release 7.5.4A). Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 2000Google Scholar

39. Bibb A, Casimir GJ: Haitian families, in Ethnicity and Family Therapy, 2nd Edition. Edited by McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Pearce JK. New York, Guilford, 1996, 97–111Google Scholar

40. Wilson WJ: When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor. New York, Vintage Books, 1996Google Scholar