Predictors of Adequacy of Depression Management in the Primary Care Setting

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Depression is most commonly treated in the primary care setting. However, most studies have shown that depression care in this setting is often inadequate. This study examined the adequacy of antidepressant treatment and overall depression management by primary care physicians and identified patient characteristics related to inadequate care. METHODS: Adequacy of depression care among patients with depression who presented to a primary care office was evaluated by using physicians' self-reports and medication prescription data. Adequacy of depression care was measured in two ways: adequacy of the current medication trial was measured by using the Antidepressant Treatment and History Form (ATHF), and adequacy of overall management by the physician was measured by using an algorithm developed for this study. The association was examined between patient characteristics and adequacy of the medication trial or depression management. RESULTS: Data were gathered for 389 patients with depression. Overall, 71 percent of patients had adequate ATHF scores, and 75 percent were judged to receive adequate depression management. No significant differences in adequacy were seen on the basis of race, age, or gender. When depressive symptoms were almost absent or extremely severe, 91 percent of patients were adequately managed; in contrast, when symptoms were mild, mild to moderate, or moderate 69 percent of patients were adequately managed. Additionally, specific medications, such as sertraline and fluoxetine, were associated with a lower likelihood of an adequate ATHF score. CONCLUSIONS: A majority of these primary care patients were adequately treated for depression, with no detectable disparity related to race or age. However, mild to moderate depressive symptoms (as opposed to remitted or severe symptoms) and specific medications were associated with a lower rate of adequacy. These findings have implications for ways that primary care physicians could be trained to more adequately manage the spectrum of severity of depression.

In all patient populations, depression is most often treated in the primary care setting; primary care physicians in the United States account for nearly half of all antidepressant-related visits and 60 percent or more of first antidepressant prescriptions (1,2,3). However, numerous studies have shown that depression care is suboptimal in the primary care setting; it is characterized by subtherapeutic dosages of antidepressants and inadequate duration of medication trials as a result of premature switching or discontinuation (4). Studies have reported rates of adequate dosing for 40 to 90 percent of patients; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the type of antidepressant most likely to be prescribed adequately in terms of dosage and duration (5,6,7,8). Thus, since the introduction of SSRIs, the proportion of patients who receive adequate medication trials has increased.

Despite this encouraging trend, disparities in the treatment of depression have been found between patients from racial or ethnic minority groups or older patients and white or younger patients (9,10,11). The prevalence of depression among African Americans is similar to that for the general population, at 15 percent (12); yet some studies have reported that African-Americans receive lower quality of care for depression than white patients (9,13,14). However, other reports have shown no racial variations in the primary care setting in prescription of antidepressants or referrals to mental health specialists (15), and reports remain mixed about the existence of racial disparities in the likelihood of patients' receiving mental health counseling and psychotherapy (16,17,18). Similarly, although depression is common in late life, few elderly patients receive adequate trials of antidepressants in primary care (11,15,19).

The study presented here was a prospective survey of the adequacy of depression management among patients who were given a diagnosis of depression by their primary care physician. This project was an analysis of a quality initiative done in practices of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Community Medicine, Inc., (UPMC-CMI), which has a prospective tracking component of care outcomes. Our aim was to identify disparities in depression care and identify patient characteristics that may predispose patients to inadequate care.

Few studies of adequacy of depression management in a community setting have incorporated depression management decisions made by primary care physicians. Studies typically have used pharmacy claims or administrative data and relied on antidepressant prescription as the sole criterion to evaluate adequacy. We used self-reports of physicians concerning their decision-making processes, patients' clinical information, and medication prescription data. Such self-reports have been shown to be accurate measures of prescription practices and can be used reliably (20). We asked whether there is a high rate of antidepressant treatment inadequacy by primary care physicians, in terms of dosage and decision making, and whether sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were predictors of treatment inadequacy.

Methods

Participants

This study was based on data from a quality assurance project of patients with depression diagnosed and treated by primary care physicians at community-based private practices owned by UPMC-CMI. Data were collected from June to September 2002, during which time primary care physicians completed tracking forms prospectively for each patient whom they were treating with an antidepressant medication. The form gathered cross-sectional patient information: gender, age, race, comorbid medical conditions, whether the patient was being treated for a first episode of depression, current antidepressant and daily dosage, duration of antidepressant therapy, and concurrent psychotropic medications. The form also indicated a rating of the severity of current depressive symptoms on a scale of 0 to 7 (0, absence of depressive symptoms; 1, almost absent; 2, mild; 3, mild to moderate; 4, moderate; 5, moderate to severe; 6, severe; and 7, extremely severe). The presence of current suicidal ideation was also noted. The primary care physicians also indicated the next step they planned to take: whether they would continue the same treatment, switch to another antidepressant, change the dosage, or refer the patient to a mental health specialist. For this analysis, tracking forms were selected only from physicians who treated both African-American and white patients, so that we could accurately assess race-related differences in care. Using these criteria, we selected 421 patients.

Adequacy ratings

We assessed the adequacy of depression care for each patient in two ways. First, we assessed the adequacy of antidepressant dosage with the Antidepressant Treatment and History Form (ATHF), a validated instrument rating the adequacy of antidepressant treatment (21). Ongoing medication trials of less than four weeks were not rated because antidepressants typically require at least four weeks to take effect and because antidepressant treatment is typically initiated with subtherapeutic dosages that are later titrated. When several antidepressants were used, each medication was rated as an individual trial. To ensure reliability, all trials were rated independently by two raters, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Second, we assessed the adequacy of overall physician depression management for each patient. This assessment was based on severity of depression, adequate antidepressant dosage as determined by the ATHF rating, adequate duration of medication trial, and physician-reported next step in depression management. Overall depression management was accordingly rated as adequate, inadequate, or equivocal.

A rating of adequate was given when a decision to continue the same treatment was made for medication trials of less than four weeks; a medication switch was made because of side effects; depression symptoms were absent or almost absent, regardless of decision; or a decision was made to increase the dosage, add a medication, or refer the patient to a mental health specialist because of depressive symptoms (mild to extremely severe) and the trial lasted more than four weeks.

A rating of inadequate was given when a decision was made to continue the same treatment even though depressive symptoms were present (mild to extremely severe) and the medication trial lasted more than four weeks or when a change in depression management, such as increasing the dosage or adding a new medication, was made before the efficacy of the current medication could be determined from an adequate trial.

A rating of equivocal was given when there was no evidence of adverse effects and a medication was switched before an adequate trial was completed or when depressive symptoms were absent or almost absent and action was taken to increase the dosage, switch medications, or refer the patient to a mental health specialist.

Data analysis

We examined associations between patient characteristics (race and age) and ATHF scores or depression management adequacy ratings with chi square tests from a locally created computer program. We also calculated the frequency of use of each antidepressant and rates of ATHF scores for each medication. We dichotomized ATHF scores as inadequate, score of 1 or 2, and adequate, score of 3 or 4. We also examined management adequacy ratings by medication.

Results

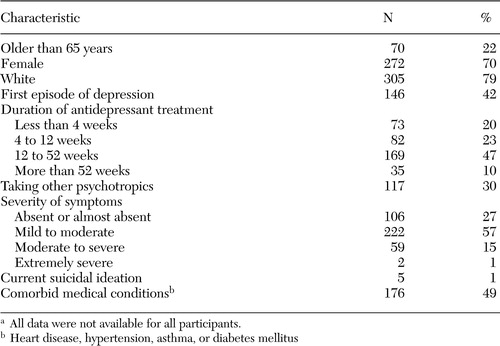

Data from 421 patients were collected. Among these patients, 32 were missing the data required to determine adequacy of treatment by either the ATHF score or the depression management score and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Thus, data from 389 patients were used in the analysis. Table 1 describes the characteristics of these patients.

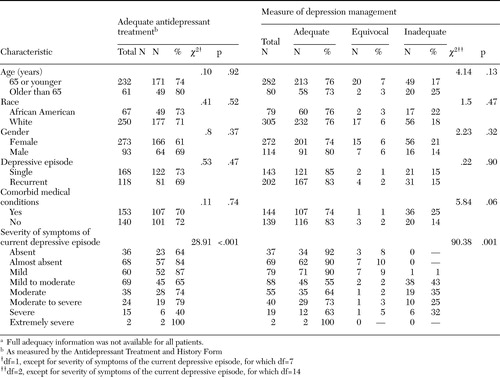

Patient characteristics and adequacy

Overall, 233 of 329 patients (71 percent; confidence interval [CI] of 68 to 78 percent) had an adequate ATHF score, and 287 of 382 (75 percent; CI of 71 to 79 percent) had adequate depression management. As shown in Table 2, an adequate ATHF score and adequate depression management were not associated with race, age, gender, depressive recurrence, or comorbid medical conditions, but adequacy ratings did vary depending on severity of symptoms. In particular, there seemed to be a U-shaped curve in terms of depression management adequacy: among patients whose symptoms were absent, almost absent, or extremely severe, almost all received adequate depression management (98 of 108 patients, or 91 percent). However, among those with mild, mild-to-moderate, or moderate symptoms, only about two-thirds received adequate management (154 of 222 patients, or 69 percent). Table 2 also shows differences in ATHF scores by depression severity.

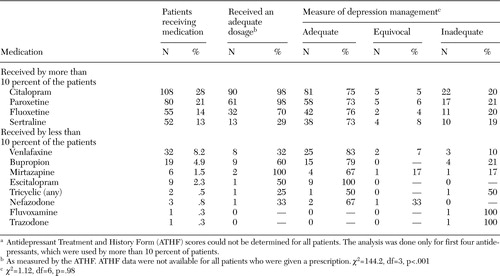

Medication use and adequacy

Table 3 shows the frequency of use of specific antidepressants and adequacy ratings associated with each. SSRIs were the most commonly prescribed group; paroxetine and citalopram were the most commonly prescribed agents. As the table shows, there were significant differences in rates of adequate ATHF scores among the SSRIs. A total of 151 of 154 patients (98 percent) who received paroxetine and citalopram had adequate ATHF scores, compared with 32 of 40 (80 percent) who received fluoxetine and 13 of 45 (29 percent) who received sertraline. The ATHF requires a sertraline daily dosage of 100 mg or more for an adequate rating, whereas the package insert recommends a daily dosage of 50 mg or more. Because the ATHF algorithm gives an inadequate score to a dosage of 50 mg, we reexamined the rate of sertraline adequacy by altering the ATHF so that a dosage of 50 mg was considered adequate; with this modification, 29 of 45 patients (64 percent) who took sertraline were adequately treated. However, this rate was still significantly lower than rates for adequate ATHF scores for paroxetine and citalopram (χ2=45.6, df=2, p<.001). In contrast to ATHF scores, depression management adequacy ratings did not significantly differ by antidepressant.

Discussion and conclusions

We evaluated adequacy of antidepressant dosage and adequacy of depression management in a sample of primary care patients within a community practice network. We found no association between demographic characteristics (age, race, and gender) and the adequacy of antidepressant dosage or depression management. Some previous studies found that African Americans and older persons may be undertreated because physicians fail to identify these patients as depressed or to initiate antidepressant pharmacotherapy with them (15). However, it seems as though once patients are given a diagnosis and treatment is initiated, adequacy of treatment is comparable to that received by white or younger patients. This finding is congruent with several recent studies that reported no differences in antidepressant therapy among African-American and white patients with a diagnosis of depression who presented for treatment in the community in a primary care setting (15,16,18).

We did find that mild to moderate depressive symptoms (as opposed to remitted or severe symptoms) were associated with a lower likelihood of adequate depression management, which suggests that dealing with residual or resistant depressive symptoms in the context of adequate antidepressant treatment remains a problematic area for primary care physicians. Because of the association between residual depressive symptoms and poor long-term outcomes (4), it is important that continuing education and other interventions that aim to improve management of depression in primary care focus on this area.

In this study, SSRIs were the antidepressant medications most commonly prescribed, which is consistent with findings from other studies (6,10,22). Among SSRIs, adequacy of treatment with sertraline was rated as markedly lower than that with citalopram or paroxetine. This may be due to the instrument that we used to assess dosage adequacy. The ATHF rates a daily dosage of 20 mg of citalopram or paroxetine as adequate, consistent with the dosages recommended in the package insert of these medications. By contrast, the ATHF requires a sertraline daily dosage of 100 mg or more for an adequate rating, whereas the package insert recommends a daily dosage of 50 mg or more. However, even when this discrepancy was accounted for by giving an adequate rating for a dosage of 50 mg, sertraline was associated with a lower rate of adequate antidepressant dosage. Thus it may be that primary care physicians would benefit from education as to the range of adequate dosages for specific medications. Another option would be to preferentially prescribe medications that have simpler dosing recommendations.

Our analysis has some limitations. Our findings pertain only to patients who were already given a diagnosis of depression and do not refer to adequacy of diagnosis of depression in primary care. Also, although physicians' self-reports have been shown to be indicative of actual prescribing and primary care physicians were asked to give data for patients who were consecutively treated, primary care physicians may have selected patients whom they were adequately treating, thus inflating the estimation of adequacy of treatment. Also, it is possible that patients who were excluded because of missing data were more likely to receive inadequate treatment. Our scale of treatment decision making has not been validated, and neither was the rating of severity of depressive symptoms. Finally, our sample of primary care physicians might not be indicative of typical antidepressant treatment adequacy, because this group received a lecture about depression treatment as part of the quality assurance initiative. However, this intervention was unlikely to make a major change in physicians' management of depression (23).

Nevertheless, our data suggest that high rates of adequacy of antidepressant treatment can be obtained in primary care, both in medication dosage and in overall management, particularly with SSRIs. Furthermore, there appeared to be no race or age disparities in treatment adequacy. However, primary care physicians were less likely to provide adequate management to patients with mild to moderate depressive symptoms, suggesting that they still have problems managing residual symptoms. Also, specific medications were associated with lower adequacy ratings, suggesting that primary care physicians could benefit from education about adequate dosage ranges. Future training focusing on these specific areas could improve the overall quality of depression management in primary care.

Dr. Joo, Dr. Mulsant, Dr. Reynolds, and Dr. Lenze are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and Dr. Solano with the department of internal medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Send correspondence to Dr. Lenze at 3811 Ohara Street, Room E835, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 389 patients with depression who were receiving care from a primary care physiciana

a All data were not available for all participants.

|

Table 2. Comparison of adequacy of treatment by demographic characteristics of 389 patients with depression who were receiving care from a primary care physiciana

a Full adequacy information was not available for all patients.

|

Table 3. Comparison of adequacy of treatment by antidepressant type among 389 patients with depression who were receiving care from a primary care physiciana

a Antidepressant Treatment and History Form (ATHF) scores could not be determined for all patients. The analysis was done only for first four antidepressants, which were used by more than 10 percent of patients.

1. Olfson M, Kerman GL: Trends in the prescription of psychotropic medications: the role of physician specialty. Medical Care 31:559–564,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Pincus HA, Tanielian TL, Marcus SC, et al: Prescribing trends in psychotropic medications. JAMA 279:526–531,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Simon G, VanKorff M, Wagner EH, et al: Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:399–408,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mulsant BH, Whyte E, Lenze EJ, et al: Achieving long-term optimal outcomes in geriatric depression and anxiety. CNS Spectrums 8(suppl 3):27–34,2003Google Scholar

5. Charbonneau A, Rosen AK, Ash AS, et al: Measuring the quality of depression care in a large integrated health system. Medical Care 41:669–680,2003Medline, Google Scholar

6. Donoghue J, Taylor DM: Suboptimal use of antidepressants in the treatment of depression. CNS Drugs 13:365–383,2000Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Weilburg JB, Oleary KM, Meigs JB, et al: Evaluation of the adequacy of outpatient antidepressant treatment. Psychiatric Services 54:1233–1239,2003Link, Google Scholar

8. Dunn RL, Donoghue JM, Ozminkowski RJ, et al: Longitudinal patterns of antidepressant prescribing in primary care in the UK: comparison with treatment guidelines. Journal of Psychopharmacology 13:136–143,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Blazer DG, Hybels CF, Simonsick EM, et al: Marked differences in antidepressant use by race in an elderly community sample:1986–1996. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1089–1094,2000Google Scholar

10. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203–209,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Unutzer J, Simon G, Belin TR, et al: Care for depression in HMO patients aged 65 and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48:871–878,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sirey JA, Meyers BS, Bruce ML, et al: Predictors of antidepressant prescription and early use among depressed outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:690–696,1999Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Snowden LR, Pingitore D: Frequency and scope of mental health service delivery to African Americans in primary care. Mental Health Services Research 4:123–130,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Harman JS, Mulsant BH, Kelleher KJ, et al: Narrowing the gap in treatment of depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 31:239–253,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly Medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51:1718–1728,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Richardson J, Anderson T, Flaherty J, et al: The quality of mental health care for African Americans. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 27:487–498,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Rollman BL, Hanusa BH, Belnap BH, et al: Race, quality of depression care, and recovery from major depression in a primary care setting. General Hospital Psychiatry 24:381–390,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Schulberg HC, Katon WJ, Simon GE, et al: Best clinical practice: guidelines for managing major depression in primary medical care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 7):19–26,1999Medline, Google Scholar

20. Oxman TE, Korsen N, Hartley D, et al: Improving the precision of primary care physician self-report of antidepressant prescribing. Medical Care 38:771–776,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Oquendo MA, Baca-Garcia E, Kartachov A, et al: A computer algorithm for calculating the adequacy of antidepressant treatment in unipolar and bipolar depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:825–833,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55–61,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Lin EH, Simon GE, Katzelnick DJ, et al: Does physician education on depression management improve treatment in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine 16:614–619,2001Google Scholar