Relationship Between Cognition and Work Functioning Among Patients With Schizophrenia in an Urban Area of India

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Employment rates and work functioning are poor among patients with schizophrenia and are related to cognitive dysfunction. This study examined the relationship between work functioning and cognition, other clinical and demographic variables, and measures of social functioning among patients with schizophrenia in an urban area of India. METHODS: This study evaluated cognitive dysfunction and work functioning among 88 patients with chronic schizophrenia. Attention, executive function, and memory were tested with a battery of neuropsychological tests. Work and social functions were evaluated with standardized instruments. RESULTS: Fifty-nine patients (67 percent) were employed, most in a mainstream environment. Moderate to significant work dysfunction was present among 21 patients (24 percent). When multivariate analysis was performed, cognitive deficits did not relate significantly to current employment status or to level of performance at work. Negative symptoms predicted employment status, and poor social functioning predicted poor work performance. CONCLUSIONS: The relationship between work and cognitive status in schizophrenia was not as strong as has been previously reported in this population. It was speculated that social factors, such as the compelling need to be employed, a supportive work environment, and the number of years of formal education, were factors underlying the high level of work functioning in this group despite cognitive deficits.

Schizophrenia is accompanied by impairments in several domains of cognitive functioning (1,2,3,4,5). Cognitive dysfunction has been found to be related to employment status and performance at work (2,6,7,8,9,10). Furthermore, disability in social functioning has been found to be related to work functioning (9,11).

Data on work functioning and cognition in schizophrenia has emerged mostly from developed countries. Work is an activity that is under considerable influence from environmental factors, including availability of employment and alternate sources of income. Reports on work functioning of patients with schizophrenia from developing counties have differed from such reports about patients from developed countries. Studies from India have shown that the annual rate of employment in a cohort of 90 patients with first-episode schizophrenia ranged between 63 and 73 percent during the first ten years of follow up (12). In another study from India, among 43 male patients with schizophrenia who had never been treated, 35 percent were employed at the time that their schizophrenia was detected (13); that percentage increased to 51 percent after one year of treatment with antipsychotics (14). These rates of employment were distinctly higher than those found in a similar population in a developed country (9,15,16). This discrepancy was attributed to differences in the social and economic environment, such as the lack of disability benefits compelling patients to work and contribute to the family's income (12). It is possible that these social factors prevalent in India could modify the known association between cognition and work dysfunction observed in populations of a developed society.

We aimed to study the employment status and performance at work of patients with schizophrenia and to examine their relationship to performance on tests of cognitive function as well as clinical and demographic variables and measures of social functioning. This was a cross-sectional study of urban patients who attended a rehabilitation center in southern India.

Methods

Study population

The study was conducted at the Schizophrenia Research Foundation (SCARF) in Chennai, India. The institutional ethical review board of the foundation approved the study. The study group comprised 100 participants aged 18 years and older (60 men and 40 women). The sample was selected from consecutive patients who attended the outpatient and day care rehabilitation centers of SCARF from 2000 to 2002. All patients who were willing to participate and gave informed consent were included. Participants were required to have a minimum of ten years of formal education. A relative living with the patient was used as the key informant. The participants fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for chronic schizophrenia, as established by interviews of the patient and the key informant and case file review. The case files recorded the longitudinal record of clinical history from multiple sources, including notes on mental status from case managers, families, and psychiatrists. A consensus of diagnosis that was made by two independent assessors (one of the authors and one psychiatrist at the research facility) was required for inclusion into the study. A complete description of the study was presented to all the participants before obtaining written informed consent.

Assessments

Psychopathology. The Positive and Negative Syndrome scale (PANSS) was used for measuring psycho-pathology (17). PANSS is composed of three subscales (positive, negative, and general psychopathology), which score a total of 30 symptoms experienced during the month before the examination. Possible scores for each item ranged from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms.

Work functioning. We used the Multidimensional Scale of Independent Functioning (MSIF) to assess work functioning (18). The scale measured independent functioning in three domains: work, education, and home. This study used the assessments made in the work domain. The information for scoring MSIF was gathered from the participants with corroboration from the key informant, a colleague, or employer. The MSIF ratings captured modal state during the month before the interview.

Work functioning was measured in three dimensions: role position, support, and performance. Role position referred to the actual job role, level of responsibility, and whether the participant was employed full- or part-time. The dimension of support assessed presence and level of involvement of support at work, such as the involvement of a job coach or a colleague. The disability experienced in fulfilling the responsibilities of the present work role with the available supports was the measure of performance at work. Possible scores on each dimension ranged from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating poorer work functioning—for example, working in nonmainstream environments, receiving more support at work, and having greater disability in work performance. Detailed anchors were provided for all ratings (18). The intraclass correlation coefficient for interrater reliability for scoring on the three dimensions ranged from .88 to .95.

Social functioning. We used the Schedule for Assessment of Psychiatric Disability (SAPD) to assess disability in social functioning (19). The instrument was developed from the Disability Assessment Schedule of the World Health Organization (20) and was standardized for use in India. Information given by both the patient and the key informant formed the basis for scoring on the instrument. The ratings were based on functioning of the patient during the month before assessment.

SAPD scored disability in three domains of functioning: general activity, social role, and occupational role. Only the domains of general activity and social role were considered for this analysis. The items in the general activity domain assessed level of self-care, leisure activity and entertainment, efficiency and speed of performance of tasks in response to social situations, and ability to cope with emergency situations with social outcomes. The social role domain measured the functioning level in household participation, communication, and social contacts by assessing the level of engagement in the social activities of the family, communication with social network, and the development and maintenance of relationships. Marital and parental role functioning were items in the social role domain that were not considered for this study because this information was available for only 16 patients (18 percent). Possible scores in each area range from 0 to 5, with 0 indicating no dysfunction and 5 indicating maximum dysfunction. The intraclass correlation coefficient for interrater reliability for rating on each item ranged from .84 to .92.

Cognitive functions. We used a battery of neuropsychological tests. To assess attention functioning, we used the digit span test (21), the visual memory span test (21), and the digit-symbol substitution test (22). To assess executive function, we used the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (23) and Ruff's figural fluency test (24). To assess memory, we used the verbal and visual paired association learning test (21), the verbal and visual reproduction test (21), and the letter-number span test (25). In addition, several tests were selected from the battery of neuropsychological tests that are available from the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) in India: the visual number scanning test to assess attention, the ideational fluency test to assess executive function, and the verbal and visual learning and memory test and the delayed response learning test to assess memory. This battery was developed and is in use at the NIMHANS in India (unpublished data, Mukundan S, 1979) and composed of tests taken from other standardized battery of tests, such as the Luria-Nebraska Neuropsychological battery. All patients were taught the English language as part of the educational curriculum throughout all levels of school, including the university level. Familiarity with English minimized problems in task performance caused by language difficulties.

Data analysis

We used chi square analyses and t tests for between-group comparisons and Pearson product-moment correlation analysis to measure the correlation between demographic and clinical factors and social functioning with performance on cognitive tasks. Two-tailed p values were considered for estimating statistical significance. For all analyses p<.01 was used as the level of significance. The variables identified as significant in the univariate analysis were entered into logistic regression analysis to identify predictors of current employment status. These variables were also entered into stepwise linear regression to identify factors that predicted degree of work dysfunction. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), release 7.5.1 was used for data analysis (26).

Results

Study population

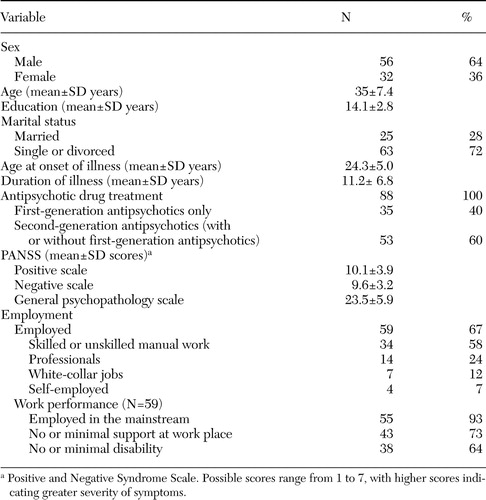

Employment before onset of illness or thereafter was not expected for 12 participants because they were full-time housewives or students. The data from the remaining 88 participants are presented here. The general demographic and clinical characteristics and work status of this population are presented in Table 1.

Variables associated with employment status

Fifty-nine participants (67 percent) were employed. The ratio of men to women was similar among participants who were employed and those who were not (38 men, or 64 percent, and 21 women, or 36 percent, in the employed group, compared with 18 men, or 62 percent, and 11 women, or 37 percent, in the unemployed group). The proportion of persons who were married was comparable in the two groups (20 participants, or 34 percent, in the employed group, compared with five participants, or 17 percent, in the unemployed group). Employment before onset of illness was also comparable in the two groups (33 participants, or 56 percent, in the employed group, compared with 15 participants, or 52 percent, in the unemployed group). The groups did not differ significantly in the medication that they received (32 participants, or 54 percent, in the employed group received second-generation antipsychotics, compared with 21 participants, or 72 percent, in the unemployed group).

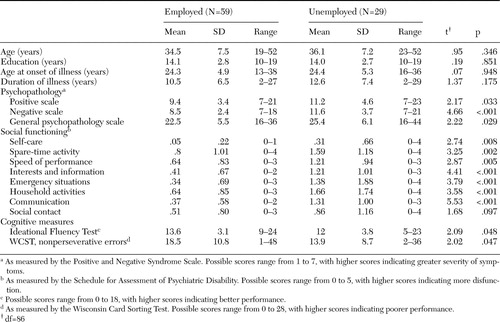

The comparison of the two groups on other variables is presented in Table 2. Persons who were employed differed significantly from those who were not on the scores of all three subscales of PANSS and all measures of social functioning. They differed on two cognitive measures: ideational fluency and the number of nonperseverative errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Scores on both of these two parameters were associated with employment status with an effect size (as an expression of strength of the association) of .45. The differences between the two groups on other neurocognitive measures were not significant. Two measures of attention (time taken on the visual scanning test and the forward digit span test) and some measures of memory (number of sets correctly responded to on the letter-number span test, delayed recall on the visual memory and learning test, and immediate and delayed recall on the visual reproduction and the visual paired-association tests) had a small effect size of .20 (27). All other cognitive variables had effect sizes of less than .20.

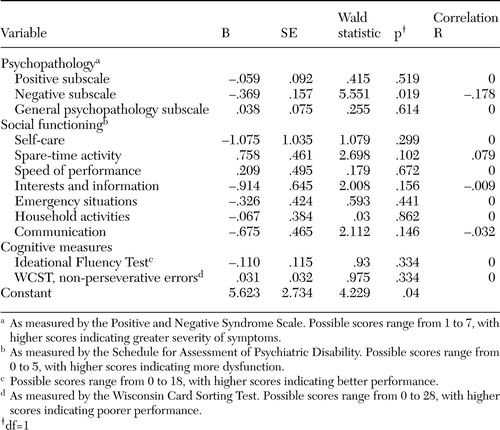

As shown in Table 3, when logistic regression analysis was performed, the PANSS negative subscale was the only predictor of employment status among variables that were significant on univariate analysis. Abstract thinking, an item on the negative subscale, could be considered a cognitive function. When this item was entered into the analysis separately, the rest of the negative subscale was still the only significant factor (beta coefficient=-.334, SE=.162, Wald statistic=4.227, df=1, p=.040).

Variables associated with disability in work performance

Men and women did not differ in their mean±SD scores of disability in work performance (4.4±3.4 for men and 4.1±3.7 for women). Married patients had mean scores that were similar to those of single patients (3.4±2.9 for married patients and 4.7±3.5 for single patients). The degree of disability did not correlate significantly with age or years of education. Patients with a moderate or significant degree of poor performance had a history of poor work performance before illness more often than those with current good performance (five of eight participants with a history of poor work performance, or 63 percent, compared with five of 25 participants with a history of good work performance, or 20 percent; Fisher's exact two-tailed p=.036).

Disability in work performance correlated with mean scores on PANSS's positive subscale (r=.240, p=.024), negative subscale (r=.444, p<.001), and general psychopathology subscale (r=.277, p=.009) but not with age at onset or duration of illness. Patients who were given a prescription for a second-generation antipsychotic had greater disability in work functioning than patients who were given a prescription for a first-generation antipsychotic (a mean score of 4.9±3.5 compared with a mean score of 3.4±3.2; t=2.04, df=86, p=.044).

A significant positive correlation was seen between disability in work performance with the following domains of social functioning: self-care (r=.310, p=.003), spare-time activity (r=.394, p<.001), speed of performance (r=.369, p<.001), interests and information (r=.473, p<.001), emergency situations (r=.404, p<.001), household activities (r=.388, p<.001), and communication (r=.511, p<.001). The work disability did not correlate with measure of social contacts.

The degree of disability in current work performance correlated with scores on the visual learning and memory test, delayed recall (r=-.326, p=.05) and on the visual reproduction test, immediate recall (r=-.354, p=.01). No significant correlation was found between work disability and scores on other cognitive tests.

Among variables that were significant at univariate analysis, only two measures of social functioning—communication (β=.363, t=3.448, p=.001) and interests and information (β=.282, t=2.686, p=.009)—were predictive of work performance on the regression analysis. The two accounted for nearly 32 percent of the variation in disability (R2=.319; F=19.893, df=2, 85, p<.001).

Discussion

The study showed that negative symptoms and social functioning, but not cognitive deficits, were related to employment and disability in performance at work. The lack of a strong relationship between cognitive deficit and work functioning was in contrast to the available evidence. In univariate analysis, some of the cognitive tasks were related to employment status and work functioning. However, these factors were not significant when multivariate analysis was performed. The number of participants was small considering the number of variables entered into the regression analyses; this restriction placed a limitation on the extent to which the negative findings of the regression analysis can be firmly supported. Two other factors need to be considered in interpreting the observations. First, the study group, living in a large metropolitan city, had potentially a better opportunity to enter the workforce than a nonurban population. Second, the study center was a specialized center for schizophrenia rehabilitation. Selection of participants from this source could have included patients who had undergone successful intervention in terms of work rehabilitation. These two factors could have helped the participants to be employed and perform better despite the cognitive impairment.

In the regression analysis, the negative symptom score was the only variable that predicted current employment status. Isolation of a putative cognitive item from the negative subscale did not alter this relationship. The relationship between negative symptoms and poor work outcomes has been well established in other studies (28,29,30). Studies have identified negative symptoms (29) or cognitive deficits (6) or both as contributing to poor work outcomes (8,30).

As has been shown in other studies, (9,11,12), we found that disability in social functioning in schizophrenia was related to work functioning. Social competence may help in securing and maintaining jobs (11). Measures of social functioning in two domains—the communication domain and the interests and information domain—strongly predicted work performance in this study. The communication domain measured the patient's communicative ability, which would be essential to get a job and maintain a good level of functioning on the job. The interests and information domain measured the individual's general level of motivation and drive to engage in social activity, which would also come into play in the work situation. Social functioning may reflect a core motivational characteristic that is often impaired among persons with schizophrenia. Patients who were motivated by social contact and leisure activities were more interested in work (9).

A note on the work environment of the study population will give a better perspective. In our study all but eight participants were working in mainstream competitive environment: four patients were working in family establishments and were not paid and four were working in sheltered employment. Participants had various jobs—such as a data entry clerk, proofreader, and security guard, which involve monotonous work—as well as jobs in health care, teaching, and marketing, which involve multitasking and require a significant level of work and social skills. Some participants worked in 9-to-5 jobs, and others (for example, manual workers and professionals) worked longer hours. Patients who were employed in regular jobs in the organized sector more freely used their sick-leave benefits. People performing below par in productivity-linked jobs in the unorganized sector did not always lose their jobs, but they received payment according to the work output. Some patients' families employed them in family establishments. These patients did not earn a wage but were productively employed. People were generally supportive of the patients at work. The education, past abilities, and social and economic background was given some credence, and this support often helped patients get and maintain jobs and provided a milieu for better performance. Some patients were able to keep their employment because their colleagues did not make an issue of their social and behavioral oddities and often supported them on assigned duties.

The large number of patients who faced full responsibility with little or no support at work could lead to questions about whether many of the patients had adequate cognitive functioning. Compared with a matched control population, the study population performed poorly on all the neuropsychological tests with medium to large effect size (data not shown). Hence the lack of a significant relationship between cognition and work functioning was not due to better cognitive ability of the population.

The number of years of formal education among our patients was notable; many patients (52 participants, or 62 percent) had completed 15 years. The high level of education of this urban population could have favored their chances of getting a job in the employment market. Although education did not emerge as a contributor to employment in this study, we believe it was a factor to reckon with. Completion of many years of academic training was also indicative of premorbid intellectual functioning and use of a high level of information processing skills in the past. The patients probably did well in work because of this inherent capability that helped them overcome any cognitive deficit of the psychosis. A parallel can be drawn with clinical manifestation of cognitive decline in neurodegenerative disorders. Years of education influenced the relationship between neuropathological changes in Alzheimer's disease and cognitive function (31). Mental stimulation occurring with many years of education delayed clinical expression of cognitive deficits in such diseases by maintaining global cognitive efficiency through enhancement of certain cognitive processes (32).

Economic pressure may be one other reason that many patients were employed despite cognitive impairments. Most families provided accommodation and care, but this was a heavy burden if the patient was not contributing financially. This burden was significant in the absence of financial support from the state to the mentally disabled, support that can be found in developed countries. This economic pressure, along with the motivational push from the family, may have motivated patients to seek a job and perform adequately despite cognitive dysfunction.

Conclusions

The rate of employment and level of work functioning did not relate to cognitive functioning in a group of patients with chronic schizophrenia living in urban India. This population differed from those reported from developed countries in their high rate of employment in the mainstream work environment. The compelling social and economic need to be in paid employment and a supportive work environment are reasons that may have counteracted any influence cognitive deficits may have on work functioning.

Dr. Srinivasan is affiliated with the department of psychological services at the Schizophrenia Research Foundation in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India 600101. Dr. Tirupati is with the faculty of health at the University of Newcastle in New South Wales, Australia, and with the department of psychiatric rehabilitation service at Hunter New England Area Mental Health in Newcastle. Send correspondence to Dr. Tirupati at James Fletcher Hospital, 72 Watt Street, Newcastle, NSW 2300, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 88 patients with chronic schizophrenia in an urban area of India

|

Table 2. Characteristics of 88 patients with chronic schizophrenia in an urban area of India, by employment status

|

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of current employment among 88 patients with chronic schizophrenia in an urban area of India

1. Elvevag B, Egan MF, Goldberg TE: Paired-associate learning and memory interference in schizophrenia. Neuropsychologia 38:1565–1575,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, et al: Neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the "right stuff"? Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:119–136,2000Google Scholar

3. McGurk SR, Meltzer HY: The role of cognition in vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 45:175–184,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rund BR, Borg NE: Cognitive deficits and cognitive training in schizophrenic patients: a review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:85–95,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kelly C, Sharkey V, Morrison G, et al: Nithsdale Schizophrenia Surveys:20: Cognitive function in a catchment-area-based population of patients with schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:348–353,2000Google Scholar

6. Bryson G, Bell MD: Initial and final work performance in schizophrenia: cognitive and symptom predictors. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders 191:87–92,2003Medline, Google Scholar

7. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:321–330,1996Google Scholar

8. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Harvey PD, et al: Cognitive and symptom predictors of work outcomes for clients with schizophrenia in a supported employment. Psychiatric Services 54:1129–1135,2003Link, Google Scholar

9. Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Mueser PR: A prospective analysis of work in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:281–296,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Penn DL, Mueser KT, Spaulding W, et al: Information processing and social competence in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:269–281,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Wallace CJ, Tauber R, Wilde J: Teaching fundamental workplace skills to persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:1147–1149,1999Link, Google Scholar

12. Srinivasan TN, Thara R: How do men with schizophrenia fare at work? A follow-up study from India. Schizophrenia Research 25:149–154,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Padmavathi R, Rajkumar S, Srinivasan TN: Schizophrenic patients who were never treated—a study in an Indian urban community. Psychological Medicine 28:1113–1117,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Srinivasan TN, Rajkumar S, Padmavathi R: Initiating care for untreated schizophrenia patients and results of one year follow-up. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 47:273–280,2001Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Ciompi L: The natural history of schizophrenia in the long term. British Journal of Psychiatry 136:413–420,1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. McCreadie RG: The Nithsdale Schizophrenia Survey: I. Physical and social handicaps. British Journal of Psychiatry 140:582–586,1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kay SR, Fiszbein S, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:262–273,1987Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Jaeger J, Berns SM, Czobor P: The Multidimensional Scale of Independent Functioning: a new instrument for measuring functional disability in psychiatric populations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:153–168,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Thara R, Rajkumar S, Valecha V: The Schedule for Assessment of Psychiatric Disability—a modification of the DAS II. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 30:47–53,1988Medline, Google Scholar

20. Jablensky A, Schwartz R, Tomov T: WHO collaborative study on impairments and disabilities in schizophrenic patients: a preliminary communication: objectives and methods. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 62(suppl 285):152–163,1980Google Scholar

21. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, Revised. New York. Psychological Corporation, 1981Google Scholar

22. Wechsler D: Wechsler Memory Scale Manual, revised. San Antonio, Psychological Corporation, 1987Google Scholar

23. Heaton RK: Wisconsin Card Sorting Text Manual. Odessa, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1981Google Scholar

24. Baser CA, Ruff RM: Construct validity of the San Diego Neuropsychological Test Battery. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2:13–32,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Gold JM, Carpenter C, Randolph C, et al: Auditory working memory and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:159–165,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. SPSS for Windows, Release 7.5.1. Chicago, SPSS, Inc, 1996Google Scholar

27. Welkowitz J, Ewen RB, Cohen J: Introductory Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences New York. Academic Press, 1972Google Scholar

28. Lysaker P, Bell M: Negative symptoms and vocational impairment in schizophrenia: repeated measures of work performance over six months. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 91:205–208,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Suslow T, Schonauer K, Ohrmann P, et al: Prediction of work performance by clinical symptoms and cognitive skills in schizophrenic outpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 188:116–118,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Hoffman H, Kupper Z, Zbinden M, et al: Predicting vocational functioning and outcome in schizophrenia outpatients attending a vocational rehabilitation program. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 38:76–82,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al: Education modifies the relation of AD pathology to level of cognitive function in older persons. Neurology 60:1909–1915,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Le Carret N, Lafont S, Mayo W, et al: The effect of education on cognitive performances and its implication for the constitution of the cognitive reserve. Developmental Neuropsychology 23:317–337,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar