Outcomes for Long-Term Patients One Year After Discharge From a Psychiatric Hospital

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this study was to evaluate effects associated with moving patients from hospital to community-based settings, to compare persons who left the hospital with those who remained in the hospital, and to address the question of whether discharge reverses institutionalism in a sample of elderly long-stay psychiatric inpatients. METHODS: The hypotheses were that, compared with the control group of patients who stayed in the hospital, those who left would have significantly better mental states, social functioning, and social networks at follow-up; that community settings would provide a significantly better quality of environment than the hospital; and that discharged patients would express a preference for community care after discharge from the hospital. The study was a prospective nonrandomized controlled trial at Cane Hill, Friern, and Claybury Hospitals in England. Sixty long-term patients with schizophrenia who were discharged to community care were compared over time with matched controls (N=131). RESULTS: No overall differences were detected in the pattern or severity of symptoms between patients who were discharged from the hospital and those who were not, and no significant changes over time were noted. Significant improvements in social networks, patients' preference for community settings, and quality of clinical environment were noted. CONCLUSIONS: These results give qualified support for moving long-stay psychiatric patients from hospital to community settings.

In the second half of the 19th century there was a rapid expansion of asylums in many of the more economically developed countries (1,2), followed by a decline in capacity over the past 50 years (3). The three components of deinstitutionalization are the prevention of inappropriate admissions to psychiatric hospitals through the provision of community facilities, the release to the community of all institutional patients who have received adequate preparation, and the establishment and maintenance of community support systems for noninstitutionalized patients (4). More succinctly, deinstitutionalization is the contraction of traditional institutional settings with a concurrent expansion of community-based services (5).

This policy has now been replicated throughout most of the economically developed world, and evidence on the cost-effectiveness of these far-reaching changes comes from several key studies (6,7,8,9,10,11,12) and reviews (7,13,5,8). The most comprehensive assessment was conducted by the Team for the Assessment of Psychiatric Services (TAPS) (14,15,16,17,18,19), which interviewed all long-term inpatients with a length of stay of more than a year at two large psychiatric hospitals in North London (5). One year after discharge, patients who had left the hospital were reinterviewed and were compared with a control group who had remained in the hospital during the study period. Few differences were found between those who left the hospital and those who did not in terms of individual patients' clinical and social outcomes one year after discharge. The benefits conferred by community placements were more diverse social networks, more autonomy, and a marked preference by patients for community rather than hospital residence (16). The TAPS findings are also notable for demonstrating that very few of the long-stay patients became homeless after discharge, that it was rare for discharged patients to engage in crime, that the mortality rate did not differ between those who were discharged and those who were not, and that the discharged patients continued to need brief hospital admissions for acute relapses of their psychotic disorders (17,18,19,20).

The study reported here tested the replicability of these findings in relation to changes in symptoms, social behavior, and social networks and added a focus on the patients' own attitudes and preferences about hospital and community care. The aims of the study were to evaluate the effects on patients of moving from the hospital to community-based settings, to compare these individuals who left the hospital with a control group who stayed on as inpatients, to address the question of whether discharge from the hospital reverses institutionalism, and to evaluate the overall success of hospital closure in the first year after discharge.

The following hypotheses were developed from a review of the relevant literature to establish the success or failure of the deinstitutionalization program. The first hypothesis was that, compared with patients who did not leave the hospital, patients who were discharged would have significantly better mental states, social functioning, and social networks at follow-up. The second hypothesis was that community settings would provide a significantly better environment than the hospital. The third hypothesis was that discharged patients would express a preference for community care after discharge from the hospital.

Methods

Study design

The study was a prospective nonrandomized controlled trial of 204 long-term psychotic patients in three long-term psychiatric institutions in London. One of the hospitals—Cane Hill Hospital in South London—was undergoing closure, and the patients constituting the discharged group for this study were ascertained at this site. The north London sites—the Friern Barnet Hospital and Claybury Hospital—remained open during this study period, and the control group of patients who were not discharged was drawn from the long-term patients who remained at those hospitals throughout the study period and received some continuing rehabilitation. The three hospitals were similar in age, purpose, and staffing, and all served deprived inner-city areas. Because a randomized controlled trial was not acceptable to the local health authorities, a matched, quasi-experimental, controlled prospective follow-up design was used—the most powerful design available. The study was given full ethical approval by the relevant local institutional review board and was conducted from October 1990 to September 1996.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The 73 patients in the discharged group who were initially identified all came from a group of long-term inpatients at Cane Hill Hospital. These patients' residential area of origin before hospital admission was Camberwell. Patients were included in the study if they had been in the hospital for at least a year at the time of study entry and if they were on adult psychiatric wards. Patients were excluded if they were in a secure forensic ward at the hospital (which was not subject to closure) or if they had a primary diagnosis of mental retardation or a dementing illness.

Study participants in the control group of patients who were not discharged (N=131) were selected from among those who remained inpatients at the Friern and Claybury Hospitals in North London throughout the study period. To increase the statistical power of the analyses, patients in the control group were matched to give a 2:1 ratio of patients who were not discharged versus those who were discharged wherever possible; however, for 15 very elderly patients in the control group, only one suitable patient was available. The same exclusion criteria were used as were used for the discharged group, and, as with the discharged group, all control patients were inpatients who met the eligibility criteria and whose original area of residence was within the catchment area of the study hospital. Discharged patients (cases) were matched to those who were not discharged (controls) on the following criteria: total Social Behavior Schedule score (matched within 3 points, from a total of possible score of 90, to ensure that patients of similar disability levels were being compared (21); age (matched within five years); and gender. Many of the patients were frail and elderly and so were not able to complete all assessments, and the varying numbers of patients included in the analyses is indicated in the tables.

Outcome measures

Interviews were conducted with all patients who were able to give valid written consent. Staff interviews provided information about patients' behavior and social networks. Follow-up interviews took place one year after discharge from the hospital for those who were discharged and one year after baseline assessments for those who were not discharged. Full details of the measures have been given elsewhere (15,22). Briefly, the measures used were the Environmental Index (EI) (an assessment of the quality of the immediate clinical and social environment, rated by the researcher; possible scores range from 0 to 37, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of environmental restrictiveness) (15); the Living Unit Environmental Scale (LUES) (an assessment of the suitability of the residential setting as a home, rated by the researcher) (23); the Patient Attitude Questionnaire (PAQ) (rated by patients, to show their views on life in the hospital and in the community, with ratings given for each item without being aggregated and with well-established reliability) (24); the Personal Data and Past Psychiatric History (PDPH) (a record of patient-level sociodemographic data from case notes) (15); the Physical Health Index (PHI) (an assessment of serious physical illness, from staff and case note sources; possible scores range from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating a greater number of physical health problems) (15); the Present State Examination (PSE 9th edition) (a diagnostic instrument, with psychopathologic features assessed on the basis of 142 items and with well-established reliability) (23); the Social Behavior Schedule (SBS) (a rating of abnormal behavior; possible scores range from 0 to 93, with higher scores indicating more disturbed behavior; has well-established reliability; the SBS Positive subscore includes ratings of incoherent or odd speech, hostile social contacts, overactivity, and laughing and talking to oneself) (21); and the Social Network Schedule (SNS) (developed by the TAPS team to assess the quantity and quality of each patient's social network; the number of social contacts in each category starts at zero and has no preestablished upper limit) (24). Costs of care were not assessed in this study.

Data analysis

Sociodemographic and basic clinical data were summarized at baseline and follow-up. Social behavior was compared between groups at follow-up; analysis of covariance was used to adjust for baseline values. Social networks were compared between groups and also over time (within groups) by using analysis of covariance and paired t tests, respectively. LUES scores were compared by using t tests at follow-up, with the ward as the unit of analysis. Attitudes of the patients who were discharged from Cane Hill hospital were summarized as percentages with 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs) (no response, unrateable response, and not applicable response were excluded).

Results

Completion rate at follow-up

Among this predominantly elderly group, of the 73 original Cane Hill patients, 13 (18 percent) died of natural causes before completion of follow-up (eight women and five men). Cause of death was recorded as pneumonia (six patients), cardiac or cerebrovascular accident (four patients), carcinoma (two patients), and unknown (one patient). No suicides were recorded. The mean age at death was 80.9 years for women and 69.4 years for men. In the control group, careful analysis indicated no differences in rates of death compared with patients who were discharged from the hospital during the study period of the TAPS project (17,25). The follow-up group of patients who were discharged therefore included 60 patients who were available for interview.

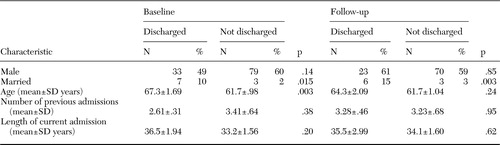

Patients' social and clinical characteristics

The study participants' sociodemographic characteristics and psychiatric histories are shown in Table 1. The two groups were similar on all matching factors. The sample was essentially an elderly, unmarried group of very-long-stay patients who had stayed in the hospital for an average of 30 years. Although almost half the patients had originally been admitted involuntarily, the large majority were in the hospital on a voluntary basis at baseline and at the time of the follow-up interviews. Few had had contact with the police or other forensic services at any time, and only three had ever been convicted of an offense.

ICD-9 diagnoses can be simply expressed: of the original 64 discharged patients for whom a complete Present State Examination was possible, 59 (92 percent) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, as did 123 (94 percent) of the 131 patients who were not discharged. The remaining 8 percent of the discharged patients and 6 percent of those who were not discharged had a diagnosis of depressive psychoses, manic-depressive psychoses, paranoid psychoses, or another diagnosis.

Accommodation and services received after discharge

Of the patients who were discharged from the hospital, only one went on to independent accommodation. Of the others, 38 percent (N=27) were accommodated in newly established services in 24-hour staffed accommodation; the remainder were discharged to staffed residential homes (N=13, or 18 percent), nursing homes (N=16, or 22 percent), or board-and-care homes (N=16, or 22 percent). In addition, all the community-based patients received domiciliary support, regular home visits by community psychiatric nurses working as direct care case managers, and regular mental state and medication reviews by treating psychiatrists, either at their homes or at local mental health centers.

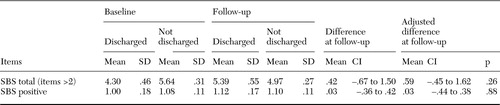

Social behavior

No differences were noted between the two groups at baseline, as can be seen in Table 2. No overall differences were noted at follow-up either, with one exception: patients who left the hospital were less likely to act on bizarre ideas. This negative finding is striking, because in the interim most of the discharged patients had been exposed to an intensive rehabilitation program and had moved from their home of 30 years in a hospital ward out into a smaller community-based house.

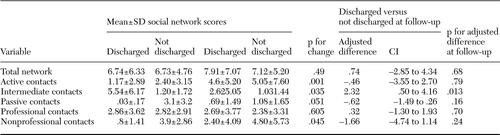

Social networks

The quality and quantity of patients' and residents' social networks are summarized in Table 3. A clinically important pattern emerged: the total network size shows a nonsignificant increase for both groups of patients, predominantly reflecting an increased number of active contacts, confiding social contacts, and friends—replacing less active contacts. This effect was larger for patients who were discharged than for those who were not, but the difference between the two groups was not significant. This finding suggests that the hospital closure program produced some limited benefits both for patients who were discharged and for those who remained as inpatients during the closure process and that the program achieved an increase in both the quantity and quality of the patients' social networks.

Physical health problems

Physical health problems were very common in this sample. Half the patients in the discharged group had at least one serious health problem, with no significant differences between the two groups. Discharge from the hospital was associated with no changes in either the number of physical health problems or the amount of treatment received, as measured with the PHI. Two of the most frequently occurring problems were incontinence and impaired mobility, which occurred among 32 percent and 16 percent of the discharged patients at baseline, respectively, and which were also found to increase in frequency with age in the TAPS study (20).

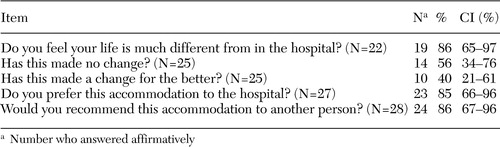

Patients' attitudes to discharge

The attitudes of both groups of patients to discharge are summarized in Table 4. After leaving the hospital, almost two-thirds of the discharged patients expressed a preference for staying in their new homes permanently. Furthermore, at least 85 percent said they preferred their new homes to the hospital and would recommend their accommodation to someone else. Notably, 40 percent of those who were discharged said that they had noticed positive changes about themselves since leaving the hospital, and only 4 percent reported negative changes.

Quality of clinical and residential settings

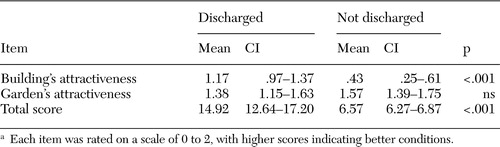

The results of the EI are clear: four of the subscales—patients' activities, personal possessions, meals, and health and hygiene—showed neither significant time effects (differences between time 1 and time 2) nor significant site-by-time effects when the analysis of covariance was conducted, whereas for two of the subscales—room characteristics and ward or residential services—significant time and site-by-time effects were noted at the p=.001 level, which show that the characteristics of the residential care facilities were far less restrictive than the conditions in the hospital. The key LUES results at follow-up are presented in Table 5. Again, the findings are clear: on every rating except two—attractiveness of gardens and cleanliness—the community sites were rated by research staff as far superior to the hospital sites.

Discussion and conclusions

No overall differences were detected in the pattern or severity of symptoms between patients who were discharged from the hospital and those who were not, and nor were any changes over time noted, which is consistent with the results of earlier research (16). Thus there was no evidence of any amelioration of the features of institutionalism one year after discharge, nor any differences in mortality rates between persons who were discharged and those who were not discharged from long-term hospital care (20). Therefore our initial optimism (that hospital discharge would be associated with a reduced level of instititutionalism) as well as our concern (that death rates would rise after hospital transfer) were both misplaced, despite very substantial changes to the patients' immediate living environments.

The results pertaining to patients' social networks were more subtle. As expected, after discharge from the hospital, patients kept contact with more staff and patients in the community and with fewer who were based in the hospital. The size of the total social network increased over time both for patients who left the hospital and for those who stayed. At the same time, more contacts were active—that is, involving a two-way exchange—rather than passive. In parallel, the number of friends and confidantes also increased for both groups of patients. The overall trend was for a modest improvement in the quantity and quality of social networks for both the discharged group and those who were not discharged. This finding suggests that the process of deinstitutionalization may confer benefits both on those who leave the hospital and on those who stay in the hospital for rehabilitation before discharge.

Our first hypothesis—that, compared with the control group, those who left the hospital would have significantly better mental states, social functioning, and social networks at follow-up—was, overall, rejected. No psychiatric or social differences were noted between groups over time, a similar finding to that of the north London TAPS study (26). Improvements in social networks were noted among patients who were discharged, but similar gains were noted in the control group of patients who were not discharged, which supports the interesting possibility that the hospital closure process produced benefits both for those who were discharged and for those who remained in the hospital during the initial stages of the closure.

Our results led us to accept the second hypothesis—that community settings would provide a significantly better environment than the hospital. On almost all the environmental measures, the community settings were rated better than the hospitals, and the main effects of leaving the hospital for patients was to offer a less restrictive social environment.

The results also gave us strong grounding to accept the third hypothesis—that discharged patients would favor community care after discharge from the hospital. For many of the discharged patients, discharge was one of the most notable events of their adult lives. They had lived in a hospital for an average of 32 years; it is difficult to imagine a more profound planned interruption to their daily routine. Before the patients left the hospital, few attitudinal differences were noted between the two groups. Only one-third of the discharged patients wanted to stay in the hospital. At follow-up, they were asked in detail about their experience of living outside the hospital, and their answers were quite clear: 86 percent said they would recommend their new home to others; these findings reinforce those of previous studies (16). This accumulating evidence does now fairly clearly establish that the large majority of long-term patients discharged within a planned reprovision program prefer their new community homes to the hospital. Much of the change in patients' attitudes can be understood in relation to the environmental quality of these community homes, which offered greater choice and autonomy for their residents in terms of everyday activities.

Interestingly, the perspective of the patients has been discussed relatively little in the literature on deinstitutionalization. Any studies that have been conducted have tended to be small and uncontrolled (27,28,29). Long-term patients themselves tend to be more optimistic than both their families and staff about their ability to live independently after discharge from the hospital (30,31,32,33) and to be more favorable about plans to transfer other long-stay patients to community-based residential settings (19,33).

The internal generalizability of the study results is reasonably strong. The patients selected for the study were representative of the wider population of all long-stay inpatients in the study hospitals. The study's external generalizability is also good in that patients who participated in studies of six other long-stay hospitals in England had very similar characteristics (34).

Our study was limited by its focus on one patient group, largely elderly, long-stay general adult patients, at the exclusion of forensic patients and acute admissions. Although more detailed in its assessments and scope than comparable studies, our study nevertheless had a relatively small sample. The views of patients' relatives were not assessed; in fact, very few patients retained any contact at all with their relatives—the average number of family members in contact with each patient was less than one at both baseline and follow-up. Because some of the patients were frail, the numbers of patients who were able to complete some of the ratings, both at baseline and at follow-up, were limited, despite the fact that up to six attempts were made to interview some patients. Because most of the patients included in the study were elderly—and in some countries would be treated through psychogeriatric rather than general adult services—the results of this study need to be applied with caution to other treatment settings, depending on their configuration for long-term patients with psychotic disorders.

In terms of the study's strengths, the patients who were discharged were selected from a defined catchment area; interview data were collected prospectively; discharged patients were closely matched with patients in the control group of nondischarged patients, with a 1:2 matching ratio to increase the power of the analyses; and a wide range of outcome measures was used, including detailed assessments of symptoms, social behavior, physical illness, social networks, patients' attitudes, and quality of the environment.

These findings reinforce and extend those of similar studies worldwide, particularly those in Australia (35), Canada (36), Finland (37), Germany (38), Italy (39), New Zealand (40), Southern Europe (41), and the United States (42,43). In effect, the service users themselves, who are the primary intended beneficiaries of the whole deinstitutionalization process, were strongly in favor of the community alternatives, which has emerged in some previous work (44,45), even though national policy in Italy has been to allow older patients who are already living in long-stay hospitals to remain there indefinitely but to change the pattern of care slowly by admitting all new patients to smaller local inpatient units (46,47). These results give further qualified support, consistent with earlier findings, for moving long-stay psychiatric patients from hospital to community settings, as long as sufficient funding is available to provide a good quality of care in the community (40).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Graham Dunn, Morven Leese, Frank Holloway, Chris Brewin, and Geoff Der. This work was undertaken while the first author was a Medical Research Council Training Fellow.

Dr. Thornicroft is affiliated with the health services research department of the Institute of Psychiatry at King's College London, De Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, England (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Bebbington is with the department of psychiatry of University College in London. Dr. Leff is with the division of psychological medicine of the Institute of Psychiatry of King's College London.

|

Table 1. Baseline and follow-up sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of 73 patients who were discharged from an English hospital to the community and 131 control patients who were not discharged

|

Table 2. Scores on the Social Behavior Schedule (SBS) at baseline and follow-up in a sample of 46 patients who were discharged from an English hospital and 119 patients who were not discharged

|

Table 3. Social networks at baseline and follow-up in a sample of 35 patients who were discharged from an English hospital and 40 patients who were not discharged

|

Table 4. Attitudes at follow-up of 40 patients who were discharged from an English hospital

|

Table 5. Scores on the Living Unit Environmental Scale at follow-up in a sample of 24 patients who were discharged from an English hospital and 30 patients who were not dischargeda

aEach item was rated on a scale of 0 to 2, with higher scores indicating better conditions.

1. Grob G: From Asylum to Community Mental Health Policy in Modern America. Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1991Google Scholar

2. Mechanic D: The scientific foundations of community psychiatry, in Textbook of Community Psychiatry. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 2001Google Scholar

3. Thornicroft G, Bebbington P: Deinstitutionalisation: from hospital closure to service development. British Journal of Psychiatry 155:739–753,1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Brown B: Deinstitutionalization and Community Support Systems. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1975Google Scholar

5. Bachrach L: Deinstitutionalization: An Analytical Review and Sociological Perspective. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976Google Scholar

6. Wright ER: Fiscal outcomes of the closing of Central State Hospital: an analysis of the costs to state government. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 26:262–275,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Braun P, Kochansky G, Shapiro R, et al: Deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients, a critical review of outcome studies. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:736–749,1981Link, Google Scholar

8. Leff J: Care in the Community: Illusion or Reality? London, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

9. Kiesler CA: Mental hospitals and alternative care: noninstitutionalization as potential public policy for mental patients. American Psychologist 37:349–360,1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Goldman HH: Deinstitutionalization and community care: social welfare policy as mental health policy. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 6:219–222,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Linn MW, Caffey EM Jr, Klett CJ, et al: Hospital vs community (foster) care for psychiatric patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 34:78–83,1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lamb HR: Deinstitutionalization at the crossroads. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:941–945,1988Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Segal SP: Community care and deinstitutionalization: a review. Social Work 24:521–527,1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Dayson D, Gooch C, Thornicroft G: The TAPS Project:16. difficult to place, long term psychiatric patients: risk factors for failure to resettle long stay patients in community facilities. British Medical Journal 305:993–995,1992Google Scholar

15. O'Driscoll C, Leff J: The TAPS Project:8. design of the research study on the long-stay patients. British Journal of Psychiatry Suppl 18–24,1993Google Scholar

16. Anderson J, Dayson D, Wills W, et al: The TAPS Project:13. clinical and social outcomes of long-stay psychiatric patients after one year in the community. British Journal of Psychiatry Suppl 45–56,1993Google Scholar

17. Dayson D: The TAPS Project:12. crime, vagrancy, death, and readmission of the long-term mentally ill during their first year of local reprovision. British Journal of Psychiatry Suppl 40–44,1993Google Scholar

18. Thornicroft G, Gooch C, Dayson D: The TAPS Project:17. readmission to hospital for long term psychiatric patients after discharge to the community. British Medical Journal 305:996–998,1992Google Scholar

19. Thornicroft G, Gooch C, O'Driscoll C, et al: The TAPS Project:9. the reliability of the Patient Attitude Questionnaire. British Journal of Psychiatry Suppl 25–29,1993Google Scholar

20. Leff J, Trieman N: Long-stay patients discharged from psychiatric hospitals. Social and clinical outcomes after five years in the community: the TAPS Project 46. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:217–223,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Wykes T, Sturt E: The measurement of social behaviour in psychiatric patients: an assessment of the reliability and validity of the SBS schedule. British Journal of Psychiatry 148:1–11,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. O'Driscoll C: The TAPS Project:7. mental hospital closure: a literature review of outcome studies and evaluative techniques. British Journal of Psychiatry Suppl 7–17,1993Google Scholar

23. Wing L: Hospital Closure and the Resettlement of Residents: The Case of Darenth Park Mental Handicap Hospital. Aldershot, Avebury, 1989Google Scholar

24. Leff J, O'Driscoll C, Dayson D, et al: The TAPS Project:5. the structure of social-network data obtained from long-stay patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 157:848–852,1990Google Scholar

25. Trieman N, Leff J, Glover G: Outcome of long stay psychiatric patients resettled in the community: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal 319:13–16,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Trieman N, Wills W, Leff J: The TAPS Project:28. does reprovision benefit elderly long-stay mental patients? Schizophrenia Research 21:199–208,1996Google Scholar

27. Okin RL, Dolnick JA, Pearsall DT: Patients' perspectives on community alternatives to hospitalization: a follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:1460–1464,1983Link, Google Scholar

28. Goering P, Sylph J, Foster R, et al: Supportive housing: a consumer evaluation study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 38:107–119,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Poulin C, Masse R: From deinstitutionalization to social rejection: the point of view of ex-psychiatric patients [in French]. Sante Mental de Quebec 19:175–194,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Holley HL, Hodges P, Jeffers B: Moving psychiatric patients from hospital to community: views of patients, providers, and families. Psychiatric Services 49:513—517,1998Link, Google Scholar

31. Pescosolido BA, Wright ER, Kikuzawa S: "Stakeholder" attitudes over time toward the closing of a state hospital. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 26:318—328,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Pescosolido BA, Wright ER, Lutfey K: The changing hopes, worries, and community supports of individuals moving from a closing long-term care facility. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 26:276—288,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Leff J, Trieman N, Gooch C: Team for the Assessment of Psychiatric Services (TAPS) Project 33: prospective follow-up study of long-stay patients discharged from two psychiatric hospitals. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1318—1324,1996Link, Google Scholar

34. Wykes T, Katz R, Sturt E, et al: Abnormalities of response processing in a chronic psychiatric group: a possible predictor of failure in rehabilitation programmes? British Journal of Psychiatry 160:244—252,1992Google Scholar

35. Trauer T, Farhall J, Newton R, et al: From long-stay psychiatric hospital to community care unit: evaluation at 1 year. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:416—419,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Lesage AD: Evaluating the closure or downsizing of psychiatric hospitals: social or clinical event? Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 9:163—170,2000Google Scholar

37. Salokangas RK, Saarinen S: Deinstitutionalization and schizophrenia in Finland: I. discharged patients and their care. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:457—467,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Hafner H: Do we still need beds for psychiatric patients? An analysis of changing patterns of mental health care. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 75:113—126,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Tansella M: Community-Based Psychiatry: Long-Term Patterns of Care in South Verona. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1991Google Scholar

40. Hobbs C, Tennant C, Rosen A, et al: Deinstitutionalisation for long-term mental illness: a 2-year clinical evaluation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:476—483,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Madianos MG: Recent advances in community psychiatry and psychosocial rehabilitation in Greece and the other southern European countries. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 40:157–164,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Okin RL, Borus JF, Baer L, et al: Long-term outcome of state hospital patients discharged into structured community residential settings. Psychiatric Services 46:73–78,1995Link, Google Scholar

43. Peterson R: What are the needs of chronic mental patients? Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:610–616,1982Google Scholar

44. Hobbs C, Newton L, Tennant C, et al: Deinstitutionalization for long-term mental illness: a 6-year evaluation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 36:60–66,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Honkonen T, Saarinen S, Salokangas RK: Deinstitutionalization and schizophrenia in Finland: II. discharged patients and their psychosocial functioning. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:543–551,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Morosini PL, Repetto F, De Salvia D, et al: Psychiatric hospitalization in Italy before and after 1978. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl 316:27–43,1985Medline, Google Scholar

47. Mosher LR: Recent developments in the care, treatment, and rehabilitation of the chronic mentally ill in Italy. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:947–950,1983Medline, Google Scholar