Medication Treatment Patterns for Adults With Schizophrenia in Medicaid Managed Care in Colorado

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study investigated the impact of Colorado's Medicaid mental health managed care program on patterns of antipsychotic medication treatment among persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. These patterns were compared with patterns of psychosocial treatment and a measure of symptom change. METHODS: Changes in study measures over time in two areas of the state where the policy intervention was implemented were compared with changes in measures in areas where it was not implemented. The study sample consisted of 235 consumers. Measures of antipsychotic medication treatment included any use in a given period, months in which a prescription was filled, and use of second-generation antipsychotics. Psychosocial treatment was measured by any use and expenditures per user. The schizophrenia subscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale was used to measure consumer outcomes. RESULTS: Probabilities of antipsychotic use in the managed care areas were stable or increased compared with the other areas. The average number of months with filled prescriptions was unchanged. Consumers served under managed care were less likely to use psychosocial treatment, and additional decreases in treatment costs were noted in one area. Difference scores for the schizophrenia subscale showed no change or positive effects for the managed care areas. CONCLUSIONS: Within the Colorado managed care program, antipsychotic medication therapy was not impaired, despite significant decreases in the continuity or intensity of psychosocial treatment, and no reduction in symptom levels was noted. Mental health managed care does not inherently impair medication therapy. Patterns of medication use appeared to be better indicators of program success than psychosocial treatment patterns and were more consistent with outcomes.

Managed care programs have become a common element in the provision of mental health services because of their promise in promoting cost-efficient and effective care. Despite the potential and popularity of mental health managed care arrangements, evaluations have shown mixed results. A clear case in point is the comparison of Medicaid mental health managed care implemented in Utah and Colorado during the early to middle 1990s (1,2). Even though organizational and financing structures were similar, consumers in Utah who had severe mental illness had worse outcomes under managed care than a control group, whereas outcomes did not differ when a similar comparison was made in Colorado.

Recent studies have also had mixed results for measures of psychotropic medication treatment. For example, when consumers with serious mental illness in Tennessee who had adhered to antipsychotic medication were shifted to TennCare's carve-out behavioral health program, they were less likely to be adherent (3), whereas no change was found among consumers with severe mental illness when they were shifted to a Medicaid managed care program in Massachusetts (4). These findings are intriguing given that typical mental health managed care arrangements carve out psychosocial treatment, such as specialty psychiatric inpatient and outpatient care, but almost invariably exclude psychotropic medication. Several seemingly important questions are raised. What expectations should we have about the impact on psychotropic medication treatment of providing psychosocial treatment in a managed care behavioral health carve-out? How should we interpret changes in psychotropic medication patterns that might result from these arrangements? How do expectations for and interpretations of effects of psychotropic medication treatment compare with those for psychosocial treatment, as well as measures of overall treatment quality and effectiveness?

The separation of psychosocial and medication treatment by organization and financing mechanisms creates different incentives for their use. Organizations that manage psychosocial benefits under a capitated agreement have strong financial incentives to conserve on psychosocial treatment expenditures, whereas psychotropic medication generally represents a "free" good. In fact, no inherent benefits would accrue to such organizations if they reduced medication use. However, there are strong incentives to maintain, if not enhance, drug therapy. Psychotropic medications may reduce the need for expensive and intensive psychosocial treatment, notably inpatient care, giving managed care organizations every incentive to use medication treatment to protect their limited resources. In such a situation, the most likely explanation for decreases in medication treatment that are attributable to managed care is poor-quality psychosocial treatment that inhibits access to or maintenance of medication treatment.

Psychosocial treatment and medication treatment should act as complements for this to be true—a perspective that is consistent with guidelines for the treatment of serious and persistent mental illnesses. Best practice involves appropriate combinations of both, and failure to provide one type of treatment—or failure to provide it effectively—may influence the effectiveness of the other. Another view is that medication and psychosocial treatments can be substituted for one another. Decreases in medication that are related to psychosocial managed care could reflect changes in psychosocial treatment that reduce the need for or duration of medication treatment. This scenario is more likely to apply to treatment of persons with less severe and persistent mental illness.

Overall, and at least for persons with severe and persistent mental illness, decreases in drug therapy resulting from psychosocial carve-outs are almost surely an indicator of reduced quality of psychosocial treatment. Decrements in the quality of psychosocial treatment and medication treatment, in turn, are likely associated with reductions in measures of treatment outcome. Alternatively, decreases in the duration or intensity of psychosocial treatment are not inherently reductions in quality and therefore may or may not be associated with either reduced medication treatment or poorer outcomes.

This pattern of relationships between psychosocial treatment, medication, and treatment outcomes is evident in the results of the evaluations of four well-studied examples of Medicaid mental health managed care programs in Utah, Colorado, Tennessee, and Massachusetts (5,6,7,8,9). All found reductions in use of psychosocial treatment. Decrements in treatment quality in Tennessee and Utah (1,3,7,9), which were documented by use of both outcome or process indicators, were found, whereas use of similar indicators uncovered no loss of treatment quality in Colorado and Massachusetts (2,4). Medication treatment patterns appear to follow the differences in treatment quality that were found. In addition to the medication treatment patterns in Tennessee and Massachusetts noted above, increases in suboptimal dosing of antipsychotics and antidepressants were found in Utah (9). In Colorado, the rate of use of second-generation antipsychotics was higher at managed care sites than at fee-for-service sites after managed care was implemented; however, the increased rate could not be clearly attributed to managed care implementation (10).

The purpose of this study was to determine the impact of a Medicaid mental health managed care program in Colorado on the continuity and extent of utilization of antipsychotic medication and psychosocial treatment and on patients' psychiatric symptoms. Previously and newly collected data from a sample of consumers who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia were used. Previous studies found significant decreases in psychosocial treatment attributable to the implementation of the managed care program but no differences in a wide variety of consumer outcomes (2,6). Given these previous studies and the issues discussed above, we hypothesized that the transition to manage care would not be associated with a reduction in antipsychotic medication. Furthermore, we expected the patterns of antipsychotic therapy to reflect the changes in consumers' symptoms, not the changes in psychosocial therapy.

Methods

Design

The study used a quasi-experimental, pre-post design derived from the implementation of mental health managed care in some parts of Colorado and not others. This design allowed for estimation of the changes in treatment patterns and consumer outcomes that were attributable to implementation of the managed care program. A key element of this program was a shift from retrospective fee-for-service reimbursement to prospective, capitation payment. Detailed descriptions of the Colorado program have been published elsewhere (2,6).

Two distinct administrative models emerged, which were used in the study. In some areas, managed care contracts were awarded directly to free-standing, nonprofit community mental health centers (CMHCs). These areas are referred to in this article as the CMHC areas. In other areas, contracts were awarded to joint ventures between a for-profit managed behavioral health care organization (MBHO) and a CMHC. These are referred to as the MBHO areas. The remaining areas of the state that retained fee-for-service reimbursement are referred to as the FFS areas.

Changes under the two managed care models were compared with changes in the FFS areas. The two-year study period was determined by the extent of available medication data spanning January 1, 1995, through December 31, 1996. Selected variables were compared over three eight-month periods (January to August 1995, September 1995 to April 1996, and May to December 1996). The program was implemented on August 1, 1995, in the CMHC areas and on September 1, 1995, in the MBHO areas, which provided one preintervention study period and two postintervention study periods.

Sample

Study participants were drawn from a sample of 522 adult Medicaid-eligible consumers with severe and persistent mental illness that was developed to investigate the impact of the managed care program in Colorado (6). Only consumers who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and who received their pharmacy benefit under fee-for-service reimbursement were selected for this study. Consumers who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia could be meaningfully compared in terms of antipsychotic medication use. Medication data for consumers enrolled in medical HMOs with a pharmacy benefit were not available for the precapitation periods.

The original sample of consumers was randomly selected from geographic areas that were matched on socioeconomic characteristics. The consumers were Medicaid-eligible adults aged 18 years and older who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder or who had at least one 24-hour inpatient stay with a primary DSM-IV diagnosis. The original sample consisted of 176 consumers from CMHC areas, 195 from MBHO areas, and 151 from FFS areas. Additional exclusion criteria used for the study reported here reduced the sample to 89 from CMHC areas, 70 from MBHO areas, and 76 from FFS areas, for a total of 235 participants. The reduction in sample size was predominately a result of excluding consumers who did not have a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Data

The Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Finance supplied Medicaid claims data for specialty mental health services that were used during the pre-managed care period and in the post-managed care period for the FFS areas. Colorado Mental Health Services provided encounter data ("shadow claims") for the same services provided by the managed care sites as well as data on use of the state hospital. Information about consumers' outcomes was collected directly from consumers, who provided informed consent, by trained interviewers employed as part of the original study. Partial data from Medicaid pharmacy claims were recently identified from an unrelated research project. These partial claims contain only the consumer's Medicaid identifier, the National Drug Classification (NDC) drug code, and the date that the prescription was filled. All pharmacy claims with NDC codes for antipsychotics that fell within the time frame of the study were identified.

Encounter data, or shadow claims, were corroborated through matching of records in the shadow claims to those in the Colorado Client Assessment Record (CCAR), which document consumers' symptoms and functioning at admission and discharge from treatment. These data were consistently collected for all consumers in Colorado's publicly financed treatment system for several years before the managed care program was implemented. Total expenditures calculated from the managed care shadow data were also compared with annual expenditure reports submitted to the Colorado Mental Health Services by the managed care organizations. In both cases, the shadow data figures compared very closely despite some differences in reporting rules and requirements.

Measures

Use of psychosocial treatment was measured as a binary variable indicating whether or not any service was received in a given period and as the sum of treatment expenditures if services were used. Treatment expenditures were log-adjusted for the typical rightward skew in individual expenditure data. For this study, psychosocial treatment included the mental health specialty inpatient and outpatient services covered under managed care. State hospital services for consumers aged 22 to 64 years, which are not covered by Medicaid and not present in the FFS claims or managed care shadow data, were also included in the measure of psychosocial treatment, because the hospital services were a close substitute for covered services and allowed comparability across age groups.

Use of antipsychotic medication was measured as a binary variable indicating whether or not any prescription for an antipsychotic was filled in a given period. It was also measured as the number of months in a given period in which at least one prescription was filled and as a binary indicator of whether or not any prescription for a second-generation antipsychotic (clozapine, risperidone, or quetiapine) was filled in a given period. Change in the schizophrenia subscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) from the pre-managed care to the post-managed care period was chosen as a single outcome measure relevant to both medication and psychosocial therapy. This measure averages symptom severity scores (on a scale of 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms) for the three positive symptom areas most closely associated with schizophrenia: conceptual disorganization, hallucinations, and unusual thought content.

BPRS scores and data on other consumer outcomes were collected across five six-month periods beginning three to six months before managed care was implemented (2). The first and fourth data collection points occurred during the second half of the first and third study periods, respectively. Outcome measurements from the second and third data collection points were combined and averaged to provide a comparable point of measurement for the second eight-month study period. Overall sample retention was high (more than 80 percent), but data were missing for some consumers. Baseline scores were included in the regression models to account for regression to the mean.

Measures of subject characteristics incorporated as control variables included age, gender, ethnicity, and whether psychosocial treatment expenditures two years before managed care were higher ("high cost") or lower ("low cost") than median expenditures for consumers treated in that two-year period.

Data analysis

All measures were summarized for the pre-managed care baseline period by area (FFS, CMHC, and MBHO). Chi square tests or F statistics were computed to assess differences in the sample characteristics across areas. Ordinary least-squares estimation was used in all analyses. Using linear regression for binary variables allows for direct interpretation of the magnitude and statistical significance of "difference in difference" results, unlike the nonlinear alternatives such as logistic or probit estimation (11).

All regression analyses used the same empirical "difference in difference" specification consistent with the general research design. Dummy variables CMHC and MBHO measured consumer differences between these areas and the FFS areas during the pre-managed care period. Post 1 and post 2 measured general trends over time. The model-by-time interactions (CMHC and MHBO post 1 and 2—that is, the first and second postcapitation periods in the study) measured the effect of managed care in that particular area and period relative to the initial differences and secular trends. The standard errors of the coefficients were adjusted to account for potential lack of independence among observations for each participant over time and for possible heteroskedasticity.

Results

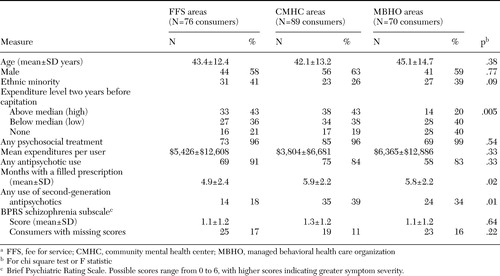

Table 1 summarizes the baseline sample characteristics by treatment site. The CMHC area sample had a lower percentage of ethnic minority consumers. Compared with the FFS and CMHC areas, the MBHO area sample had a similar percentage of low-cost consumers but half the percentage of high-cost consumers and twice the percentage of consumers with no prior service history. Consumers from the managed care areas averaged one more month with a filled prescription than those in the FFS areas. Use of second-generation antipsychotics was more prevalent in both the managed care areas than in the FFS areas.

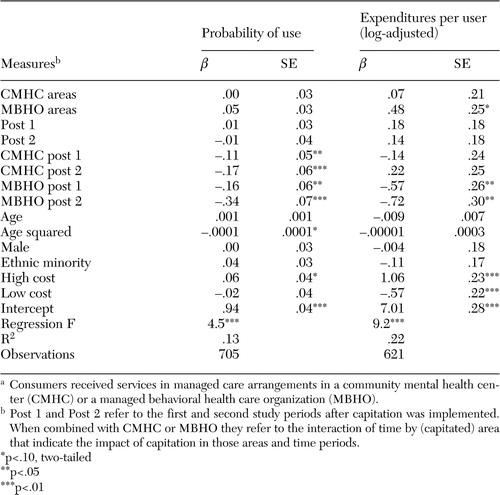

Table 2 presents the results of the regression analyses on measures of psychosocial treatment use. The first set of coefficients for CMHC and MBHO post 1 and 2 (column one) are all negative and statistically significant. These coefficients indicate the percentage reductions in the probability of use related to managed care. The second set of coefficients for these variables (column four) shows statistically significant declines in the MBHO areas. The coefficient for the MBHO variable also indicates that expenditures before managed care were slightly higher than in the other two areas.

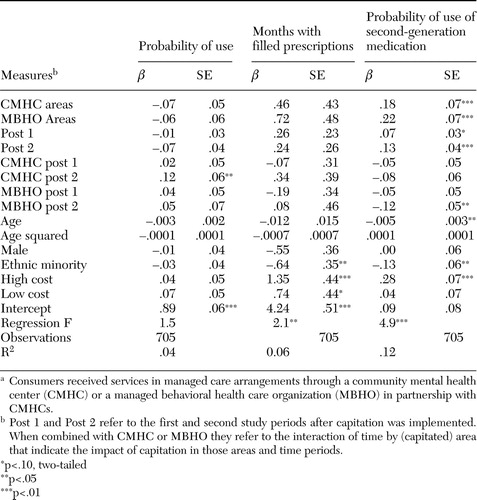

Table 3 presents the results from analyses of measures of antipsychotic use. Results in the first column are from the analysis of the probability of using an antipsychotic medication. Only the CMHC post 2 coefficient is statistically significant. Overall, these results suggest that antipsychotic use increased after managed care in the CMHC areas. The same coefficients in column four do not indicate differences in average number of months with filled prescriptions attributable to managed care.

Table 3 also presents findings for second-generation antipsychotic use. Interpretation of these results is slightly more complex. First, the CMHC and MBHO coefficients measuring pre-managed care differences are positive and statistically significant. They indicate higher levels of baseline atypical antipsychotic use among the consumers in these areas. The post 1 and 2 coefficients indicate an increasing rate of atypical use in the FFS areas. The CMHC and MBHO post 1 and 2 coefficients are negative with absolute values at or below the positive post 1 and 2 coefficients. Overall, these data indicate that the (initially higher) levels of atypical use were maintained or slightly increased in the managed care areas but the FFS areas made up significant ground by the second year after managed care.

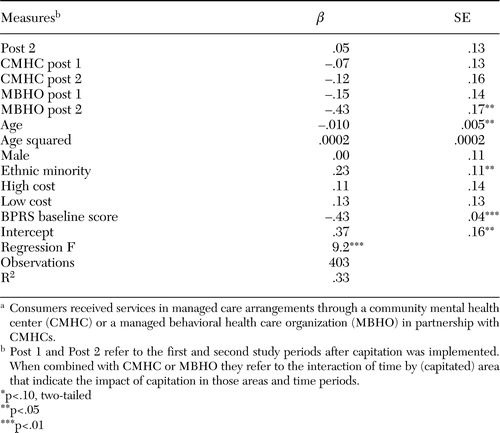

Table 4 presents the results of the analysis of the change scores for the BPRS schizophrenia subscale. Because the dependent variable is a change score (from the pre-managed care baseline), there are no separate variables for pre-managed care conditions by area, only the baseline score. The MBHO post 2 coefficient is negative—that is, in the direction of symptom improvement—and statistically significant.

Discussion

In the context of the sample and measurements used for this study, the findings supported the hypotheses initially proposed. The Medicaid mental health managed care program in Colorado did not decrease use of antipsychotic medications for consumers who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and in some cases appeared to increase their use. The findings for antipsychotic use are mirrored by the maintenance or decrease of symptoms measured by the BPRS change score. At the same time, the reductions in psychosocial treatment that were evident under managed care were not associated either with changes in medication use or with treatment outcomes as measured. This picture is consistent with a positive definition of care management in which individual consumers are selected into treatment patterns on the basis of effectiveness and efficiency. This implies reductions in treatments that may have been previously overprescribed, such as psychosocial treatment, and maintenance or increases in treatments that may be adequately or underused, such as medication therapy.

Some limitations of this study should also be recognized. The small sample allowed only for detection of moderate to large effects. At the same time, the results for psychosocial treatment were strongly consistent with results based on the full sample (6) and as yet unpublished results for the full population of treated consumers with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Similarly, the results for second-generation antipsychotic use (post-managed care) and outcomes are consistent with the results of previous studies of the full sample (2,10). Thus, to the extent that this small sample appears representative of its larger population, the greater efficiency of a larger sample would continue to support, if not enhance, the findings in regard to the hypotheses presented.

Unobserved differences among consumers across areas and between managed care and other service systems may have influenced the study results. The sample represents only adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, a class of consumers that is expected to be particularly sensitive to inappropriate changes in treatment patterns. The measures of medication use are quite general and do not account for potentially important treatment characteristics such as dosage. Finally, the single outcome measure may not adequately capture effects of both psychosocial and medication treatment patterns.

Conclusions

The combined findings of this study and those of the Utah, Tennessee, and Massachusetts studies discussed in this article suggest that changes in patterns of psychiatric medication use that are attributable to typical mental health managed care arrangements that carve out psychosocial treatment may be a strong proxy for changes in the quality of the psychosocial treatment provided. Specifically, decreases in medication treatment appear to be a consistent indicator of decreases in the quality of psychosocial treatment, whereas decreases in the amount of psychosocial treatment do not. As such, medication treatment patterns may be more closely associated with overall treatment outcomes.

Further investigation of the medication therapy patterns under managed care in the context of more current treatment conditions and for other important consumer groups that have experienced change in psychosocial treatment, such as children and adolescents (12,13,14), would help determine whether these results can be generalized. Psychosocial and medication treatment may act as either substitutes for or complements to different consumers, between specific types of medication and psychosocial treatment, and across different periods in an episode of treatment. The imposition of distinct (or even similar) organizational and financial arrangements on these two central modes of psychiatric treatment is likely to have important effects on combined treatment patterns and merits greater understanding and further research.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grant R01 54136, Capitating Medicaid Mental Health Services in Colorado, from the National Institute of Mental Health (Joan Bloom, Ph.D., principal investigator).

Dr. Wallace is affiliated with the division of public administration of the Mark O. Hatfield School of Government at Portland State University, P.O. Box 751, Portland, Oregon 97207-0751 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Bloom and Dr. Hu are with the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Libby is with the department of psychiatry of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver.

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of a sample of 235 Medicaid-eligible consumers with schizophrenia, by treatment sitea

aFFS, fee for service; CMHC, community mental health center; MBHO, managed behavioral health care organization

|

Table 2. Regression analysis of measures of the use of psychosocial treatment by 235 Medicaid-eligible consumers with schizophrenia, by treatment sitea

aConsumers received services in managed care arrangements in a community mental health center (CMHC) or a managed behavioral health care organization (MBHO).

|

Table 3. Regression analysis of measures of the use of antipsychotic treatment by 235 Medicaid-eligible consumers with schizophrenia, by treatment sitea

aConsumers received services in managed care arrangements through a community mental health center (CMHC) or a managed behavioral health care organization (MBHO) in partnership with CMHCs.

|

Table 4. Regression analysis of BPRS schizophrenia subscale score for 214 Medicaid-eligible consumers with schizophrenia, by treatment sitea

aConsumers received services in managed care arrangements through a community mental health center (CMHC) or a managed behavioral health care organization (MBHO) in partnership with CMHCs.

1. Manning WG, Liu CF, Stoner TJ, et al: Outcomes for Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia under a prepaid mental health carve-out. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 26:442–450,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cuffel B, Bloom JR, Wallace N, et al: Two year outcomes of fee for service and capitated Medicaid programs for the severely mentally ill. Health Services Research 37:341–360,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ray WA, Daugherty JR, Meador KG: Effect of a mental health "carve-out" program on the continuity of antipsychotic therapy. New England Journal of Medicine 348:1885–1894,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Dickey B, Normand ST, Hermann RC, et al: Guideline recommendations for treatment of schizophrenia: the impact of managed care. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:340–348,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Stoner T, Manning W, Christiansen J, et al: Expenditures for mental health services in the Utah prepaid mental health plan. Health Care Financing Review 18:73–93,1997Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bloom JR, Hu TW, Wallace N, et al: Mental health costs and access under alternative capitation systems in Colorado. Health Services Research 37:315–340,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Chang CF, Kiser LJ, Bailey JE, et al: Tennessee's failed managed care program for mental health and substance abuse services. JAMA 279:864–869,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Psychiatric Services 48:1147–1152,1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Popkin MK, Lurie N, Manning W, et al: Changes in the process of care for Medicaid patients with Schizophrenia in Utah's prepaid mental health plan. Psychiatric Services 49:518–523,1998Link, Google Scholar

10. Bloom JR, Cheng JS, Hu TW, et al: Use of anti-psychotic medications in treating schizophrenia among different financing and delivery systems. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 6:163–171,2003Medline, Google Scholar

11. Ai C, Norton EC: Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economic Letters 80:123–129,2003Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Catalano RA, Libby AM, Snowden LR, et al: The effect of capitated financing on mental health services for children and youth: the Colorado experience. American Journal of Public Health 90:1861–1865,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Libby AM, Cuellar A, Snowden LR, et al: Substitution in a Medicaid mental health carve-out: services and costs. Journal of Health Care Finance 28:11–23,2002Medline, Google Scholar

14. Snowden LR, Cuellar AE, Libby AM: Minority youth in foster care: managed care and access to mental health treatment. Medical Care 41:264–274,2003Medline, Google Scholar