Assessment of Medicaid Managed Behavioral Health Care for Persons With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This five-site study compared Medicaid managed behavioral health programs and fee-for-service programs on use and quality of services, satisfaction, and symptoms and functioning of adults with serious mental illness. METHODS: Adults with serious mental illness in managed care programs (N=958) and fee-for-service programs (N=1,011) in five states were interviewed after the implementation of managed care and six months later. After a multiple regression to standardize the groups for case mix differences, a meta-analysis using a random-effects model was conducted, and bioequivalence methods were used to determine whether differences were significant for clinical or policy purposes. RESULTS: A significantly smaller proportion of the managed care group received inpatient care (5.7 percent compared with 11.5 percent). The managed care group received significantly more hours of primary care (4.9 compared with 4.5 hours) and was significantly less healthy. However, none of these differences exceed the bioequivalence criterion of 5 percent. Managed care and fee for service were "not different but not equivalent" on 20 of 34 dependent variables. Cochrane's Q statistic, which measured intersite consistency, was significant for 20 variables. CONCLUSIONS: Managed care and fee-for-service Medicaid programs did not differ on most measures; however, a lack of sufficient power was evident for many measures. Full endorsement of managed care for vulnerable populations will require further research that assumes low penetration rates and intersite variability.

The term "managed care" refers to an array of practices and mechanisms designed to control cost and integrate the financing and delivery of care (1). Foremost among these practices, and the focus of this study, is capitation or prepayment on a per-enrollee basis. Medicaid managed care programs proliferated in the 1990s, and despite the withdrawal of commercial managed care organizations from the Medicaid market, the proportion of Medicaid enrollees in managed care has continued to expand; nearly 60 percent of beneficiaries were enrolled in such programs in 2003 (2). Despite the managed care industry's general retrenchment from the prototypical techniques of cost containment, notably risk sharing (3), about four-fifths of Medicaid managed care enrollees are in risk-bearing programs (4). Given that Medicaid now funds half of the public mental health services provided by the states, a proportion that is expected to grow (5), these trends have important implications for the entire system of care for persons with serious mental illness.

A substantial body of research on the impact of managed care in general, and managed behavioral health care specifically, has now accumulated, but considerable uncertainty remains (6). Most studies indicate that managed care is generally effective at containing costs, although whether this represents true efficiency is open to question (7,8). Findings related to quality, access to services, outcomes, and satisfaction, particularly for persons with disabilities, continue to be mixed or inconclusive (9,10,11,12,13).

Proponents of managed behavioral health care assert that it provides the means to contain costs and at the same time improve service access, quality, and outcomes (14). Detractors are concerned that the financial incentives in capitated managed care will lead to poorer quality of care (15,16).

These assertions can be construed as a set of hypotheses. We refer to the assertion that managed care controls costs while improving care as the panacea hypothesis and to the countervailing view that managed care results in poorer care across the board as the perverse-incentive hypothesis. The equivalence hypothesis addresses a third possibility—that managed care has no identifiable effect, positive or negative, on quality and outcomes, perhaps because organizational and financing characteristics are too far removed from provider practices or because effect sizes are too small given the measures and data. A fourth hypothesis, the mixed-effects hypothesis, is that the effects of managed care vary for different impact areas or subgroups because of the complex patterns of financial and clinical risk associated with different subpopulations.

One version of the mixed-effects hypothesis is that managed care negatively affects only the more disabled, chronically ill subgroups of enrollees, particularly if they constitute only a small proportion of enrollees (17,18). An alternative version, tested here, is that the panacea hypothesis applies to persons who have more severe disorders, whereas the perverse-incentive or equivalence hypothesis applies to those with less severe disorders—the rationale being that the needs of the most severely ill are so evident and so costly if they are ignored that even a minimally adequate system will be compelled to respond appropriately, whereas the less apparent needs of less severely ill consumers may be neglected in a substandard system of care (19).

An extension of these hypotheses is that the effects of managed care relative to fee for service may change over time: the negative effects of poor quality may become evident only after a prolonged period (20,21), or plans may perform poorly during a start-up phase but improve over time as the result of "organizational learning" (22).

A number of research and evaluation studies have tested these hypotheses by examining the experience of persons with serious mental illness in Medicaid managed care programs (23,24,25), but the Managed Care for Vulnerable Populations Study sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which is the basis of this report, is the only initiative to conduct, on this scale, a regionally diverse, multisite comparison of fee for service and managed care with respect to utilization, quality, and outcomes of behavioral health care. We report findings from random-effects meta-analyses of group differences across these five sites (26) and also bioequivalence findings that indicate whether the differences between fee for service and managed care were small enough to suggest equivalence (27). Through additional post hoc analyses, we explored the evidence for time effects—that is, whether the effects of managed care are related to the duration of enrollment in managed care (dose effect) or to program maturation (organizational learning).

Methods

Design

This observational study was designed to produce evidence to test the validity of the alternative hypotheses, using survey data on service utilization, quality, outcomes, satisfaction, and other experiences of care for adults with severe and persistent mental illness in Medicaid fee-for-service and managed behavioral health programs at five sites. Participants were interviewed twice, once soon after implementation of the managed care program and again after six months. Although the evidence from this study is necessarily less conclusive than if participants were randomly assigned to either of the two conditions, and the six-month interval was not sufficient to identify long-term effects for a population with chronic illness, the design was influenced by the rationale of obtaining timely information about possible adverse effects of managed care for this high-use vulnerable population that would signal a need for immediate policy correction.

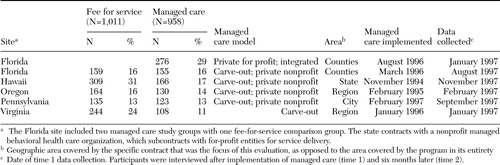

Sites

The study compared enrollees in managed care and fee-for-service behavioral health care programs in Oregon, Hawaii, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Florida. Table 1 presents information about each of the study sites. By design, the sites represent a diversity of ownership types (for-profit, private nonprofit, and public nonprofit), models of managed care (carve-out and integrated health maintenance organizations, with Florida having one of each), urban and rural populations, and program maturity. All the managed care organizations across the five sites were at full risk in their contracts with the state Medicaid agencies, although only Florida and rural Oregon put their providers (community mental health centers) at risk. Additional details on plan characteristics at each site are available elsewhere (28).

Participants

None of the study sites randomly assigned participants to the managed care and fee-for-service conditions. One of the sites drew a stratified random sample from the pool of eligible persons in managed care and fee for service. Another contacted all eligible managed care enrollees and asked them to participate in the study; all who consented were enrolled, and a matched sample was drawn from persons in fee for service. Three of the sites obtained convenience samples by interviewing persons from lists of eligible participants until they obtained a requisite number. Study participants were recruited in 1997 and 1998. Participants were paid between $10 and $20 per interview depending on the site. Written informed consent was obtained for all interviews, and approval was obtained from institutional review boards at each of the sites. More information about the selection and recruitment procedures is available elsewhere (29).

The number of participants with data at both interview points across the five sites was 1,969—a total of 958 managed care participants and 1,011 fee-for-service participants. All the participants were adult Medicaid enrollees with severe mental illness. All sites achieved at least 100 percent of the intended sample size with the exception of Florida, which achieved 93 percent.

Data collection

The study collected information by means of a sample survey using a common interview form and from claims and encounter data. This article presents results of the survey. Findings from the claims and encounter data are presented elsewhere (30).

The study followed a common research protocol to collect comparable information at each of the five sites by means of a survey administered after implementation of managed care and again in six months to a sample of participants enrolled in managed care and fee-for-service programs at each site. Interviews were conducted primarily by telephone and in some cases by having participants fill out the survey form themselves. Because the six-month period between first and second interviews was not adequate for identifying meaningful changes in this population, which had chronic and multiple comorbid conditions, the second measurement period served primarily as a check on the consistency of findings from the first.

Overall attrition rates between the first survey (time 1) and the second survey (time 2) were 12.4 percent for fee-for-service participants and 17.6 percent for managed care participants. Residualizing dependent measures at time 2 as well as at time 1 statistically controlled any between-condition effects of this differential attrition. However, residualization does not address why attrition rates differed under the two conditions. The reasons for attrition reported by the sites included inability to locate the participant or no response—the most common reason—and relocation, refusal to be interviewed, and death.

Measures

The survey included questions about service use, service quality, symptoms and functioning, satisfaction, and other experiences of care. Measures with demonstrated reliability and validity were used when available. For measures developed for the study, investigators at each site conducted their own reliability tests. (The survey and sources of measures used are available from the first author.)

Demographic variables included age, gender, race or ethnicity, and education. Clinical variables included self-reported disabilities and psychiatric problems, age at first mental health problem and at first mental health treatment, diagnosis (obtained from administrative or claims data), and severity as indicated by the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (31).

Access was measured by the commonly used proxy of penetration rates (percentage of an enrolled population receiving a service) (32). These rates were calculated from questions in the consumer survey component of the Mental Health Statistics Improvement Program (MHSIP) Consumer-Oriented Report Card (33,34). Participants were asked whether they had received a service in the past three months, the number of times they had received the service, and for how long they received the service. In addition, they were asked open-ended questions about numbers and types of medications received, including a specific question about second-generation antipsychotic medications.

Service quality was measured by means of the access and appropriateness scales of the MHSIP Consumer-Oriented Report Card Survey. Satisfaction was measured by using the satisfaction scale from the MHSIP consumer survey. Some of these items were modified slightly to broaden the focus to a "mental health plan" rather than a "program." In addition, investigators included some questions adapted from a preliminary version of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey for Behavioral Health and Substance Abuse (35). Integration of mental and physical health care services was measured as the percentage of participants who received any medical care and the percentage who received mental health care in a primary care setting, as well as the number of hours of these services that were received.

Outcome measures included symptom severity, as measured by the depression and psychoticism scales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (31) and the Global Severity Index from the BSI; health status, as measured by the SF-12 Health Survey (36); and recovery-oriented outcomes, as measured by the outcomes index of the MHSIP consumer survey. In addition, participants were asked about the extent of paid employment and victimization.

Further description of the design, methods, and results of the study are available from project reports (29,30).

Statistical analyses

Analysis of survey information consisted of comparing fee-for-service and managed care programs on the basis of 34 variables after the analyses adjusted for case mix covariates. The analysis involved several steps. First, we standardized the groups by adjusting for case mix differences in a multiple regression. Next, effects of managed care and fee for service at each site were synthesized and compared in a meta-analytic random-effects model. Finally, methods adapted from bioequivalence analysis were used to determine whether the differences between the groups, in addition to being statistically significant or not, also reached a threshold for clinical or policy relevance. A post hoc analysis examined the possibility of managed care program maturation (organizational learning) and length of enrollment in managed care (dose effects) at the site level. All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS version 11.5 (37) with the exception of all meta-analyses, which were performed by using SAS version 8.0 (38). We wrote macros to perform analyses in SAS and used SPSS for residualization and regression and descriptive analyses.

Case mix adjustment. Any analysis that combines data from multiple sites must identify and adjust for differences among groups at each site that might otherwise obscure or exaggerate actual differences in effects. A series of regression equations was performed on all outcome measures, controlling for possible demographic and clinical covariates or confounders (39). Covariates were gender, ever married, now married, education (at least some high school or no high school), race (white or nonwhite), Hispanic, disabled, and age at first treatment. Because these clinical and demographic variables might interact with site for a particular outcome, adjustment for each of the sites was made separately. After residualization of the outcome variables, the overall mean for each regression equation was added back into the outcomes for each participant. This step served to increase the scores for subsequent analyses and also allowed for interpretation of means and percentages in the original measurement metric.

Differences between managed care and fee-for-service groups may be a result of selective enrollment (attracting healthier and therefore lower-cost consumers and avoiding enrolling those who are likely to have higher costs) or selective retention (disenrollment of high-cost consumers). In addition to statistically controlling for these selection effects by means of residualization, we explored the feasibility of testing for selection by examining the association between enrollee risk factors (clinical and demographic characteristics likely to influence utilization) and other factors, such as the length of time that participants had been enrolled in managed care and whether or not they switched plans. We also compared the subgroups of persons newly enrolled in managed care plans with those newly eligible for fee-for-service programs, on the assumption that differences between them might reflect selective enrollment.

Meta-analysis of differences. Meta-analysis is commonly used to synthesize the results of independently conducted published studies. However, it can also be used to combine the results of coordinated but independently conducted multisite studies (40,41). Meta-analytic methods have the advantage of providing comparable information on group differences within individual sites as well as an overall measure of differences that combines information from all sites. This information can be used to make judgments about combining results and, further, to investigate the differences among studies or sites (42).

Both fixed-effects models and random-effects models were used to synthesize the data over all sites. The fixed-effects model was used to calculate Cochran's Q statistic to test for significant heterogeneity among sites. When the test is not significant, it is reasonable to assume that all the studies are from the same population with identical within-study variability. When the test is significant, the studies are heterogeneous, and the random-effects model is used. Results of the random-effects model are reported here, and significant heterogeneity is noted when it was present.

Because of different weighting and adjustment for between-site variability, larger sites have less effect on the random-effects estimate than on the fixed-effects estimate. Confidence intervals are generally wider in the random-effects model because estimates of variance are larger as a result of adjustment for between-site variability. The standard level of p<.05 was used in all analyses as the criterion for rejection of the null hypothesis.

Equivalence analysis. A statistically significant difference between programs may not necessarily be relevant from a clinical or policy perspective. That is, even though a statistically significant difference is found, two programs may or may not be equivalent for practical purposes. Using methods similar to those recommended by Rogers and others (27,43,44), this analysis estimated the "equivalence" or "nonequivalence" of managed care and fee for service with reference to the clinical and policy relevance of their differences.

Equivalence testing is based on the method of bioequivalence used by the Food and Drug Administration in determining whether a new drug is acceptable as an alternative to one previously approved (27). In this context, equivalence analysis is a method for estimating whether a difference between groups, if one exists, is smaller than some predetermined threshold to the extent that the results warrant consideration as equivalent for clinical or policy purposes. In the analysis of differences between managed care and fee for service, this step is necessary to identify whether the significant differences identified in the meta-analysis are meaningful differences for policy makers or clinicians. In addition, equivalence analysis indicates whether differences that are not statistically significant may be the consequence of small samples or large variability rather than an indication of actual equivalence between the entities being compared.

Equivalence boundaries are established a priori, and equivalence or nonequivalence is determined by calculating a confidence bound for the effect size. The conventional standard for accepting bioequivalence of drugs is that the group mean for the test drug be within plus or minus 20 percent of the group mean for the previously established drug for a given outcome. Because no standard equivalence range has been established for policy relevance between managed care and fee for service (or other psychosocial treatment interventions) that is comparable to the range for drug trials, we took a more descriptive approach and computed multiple ranges of 5, 10, and 20 percent. We performed equivalence analyses on the residualized data with the overall mean added. As a result, the values computed for each equivalence range were in the range of the outcomes as measured (personal communication, Banks S, 2000).

Difference testing and equivalence analysis performed together yield four possible results: different and nonequivalent, meaning that there is a difference between group means, and it is meaningful—that is, relevant for clinical or policy purposes; different but equivalent, meaning that there is a difference, but it is trivial; not different and equivalent, indicating that the two conditions are commensurate; and not different but not equivalent, indicating that the variability is too great relative to the effect size to interpret. The category of different but equivalent (category 2) indicates a study that is overpowered—that is, there is a difference but it is trivial. Not different and not equivalent (category 4) indicates that the study is underpowered for purposes of that particular variable or contrast.

Subgroup analyses. To assess the possibility of differential effects among subgroups of consumers (the mixed-effects hypothesis), we conducted separate analyses for consumers with high symptom ratings compared with low ratings, diagnoses of affective disorder compared with "other disorders," and enrollment in for-profit plans compared with nonprofit plans.

Post hoc time effects analyses. Although the measurement interval of approximately six months between baseline and time 2 was too short to permit a true longitudinal analysis, we did compare results at the two points to identify any suggestion of a time effect and found little or no difference.

To further explore the effect of time and to confirm our finding of little difference between the two periods, we conducted a post hoc analysis of the relation between the longevity of the respective managed care programs and the magnitude of the differences between the managed care and fee-for-service groups. Longevity of the managed care programs (time from date of implementation to first study interview) ranged from two to 36 months. This approach consisted of a time-series analysis of site effects to test for significant trends over time, because sites varied in duration of managed care implementation. Significant slopes in these regression curves would indicate a difference in the effect of managed care on a service because the program was implemented for a longer period. The effect sizes in the analysis compared the difference between managed care and fee for service.

Results

The mean±SD age of the sample overall (N=1,969) was 43±10.43 years. A total of 1,153 participants (58 percent) were female; 1,054 participants (54 percent) were nonwhite, and 244 (12 percent) reported Hispanic background. About two-thirds (1,239 participants, or 63 percent) had completed high school. Just over half (1,016 participants, or 51 percent) had ever married, and 203 (10 percent) were currently married. The mean age at onset of the first mental health problem was 20.6±10.9 years, and the mean age at first treatment was 24.4±10.3 years. (Data for some of these variables were missing for some participants.)

As determined by the bioequivalence methods described above, managed care and fee-for-service groups were statistically different and nonequivalent in the categories of percentage ever married, percentage Hispanic, and age at first problem. Furthermore, these percentages were affected by attrition from the first to the second interview periods.

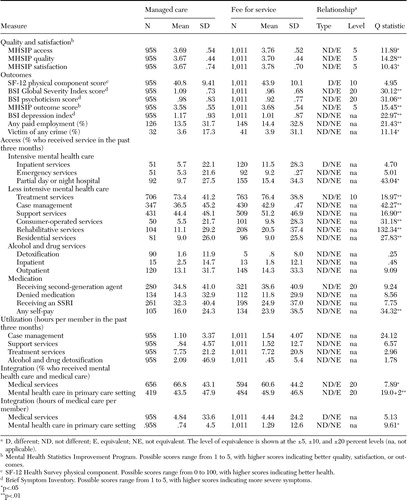

Table 2 shows the results of testing for difference and equivalence between managed care and fee-for-service groups across the five sites, along with Q statistic tests of heterogeneity of sites. Measures are grouped into five domains: quality and satisfaction; outcomes; access, measured as service penetration rates; utilization, measured as the amount of service received; and integration, measured as the use of medical care and mental health services provided through primary care. For ease of interpretation, we present only findings at time 2; differences from time 1 are discussed below. As noted above, the difference-equivalence analysis represented by the column headed "Relationship" in Table 2 used dependent variables residualized by demographic and clinical variables to control for differences among the populations of each site; however, for ease of interpretation the means reported here represent unresidualized scores.

Managed care and fee for service differed significantly on only three of 34 variables, one each in the domains of outcomes (health status as measured by the SF-12), access (percentage of enrollees who received inpatient services), and integration (amount of medical services received). Managed care and fee for service were different and nonequivalent only on two of these (the access and integration measures). The average score on the SF-12 physical component was significantly lower (less healthy) for the managed care group (40.8 compared with 43.9 for the fee-for-service group, p<.05) but still within the most conservative equivalence range of 5 percent. More hours of medical services were received under managed care (4.84 compared with 4.44 for the fee-for-service group, p<.05), a difference that was equivalent on the basis of the 10 percent range. We found no relationships of difference and nonequivalence in either the quality and satisfaction or the utilization domains. Overall, more than half of the measures resulted in relationships that were not different and not equivalent, indicating that the study was underpowered in these areas.

On many measures, the sites were relatively heterogeneous in their effect, as indicated by a significant Q statistic for 20 of the 34 measures (Table 2). However, the degree of heterogeneity varied from one measure to another, as indicated by the variation in the size of the Q statistic. This degree of heterogeneity supports the suggestion that site-specific characteristics accounted for more of the difference between managed care and fee for service than some underlying feature of managed care that was common to all sites. However, the lack of sufficient power (no difference and not equivalent) for many measures prevents this interpretation from being conclusive.

Separate analyses comparing consumers with high and with low symptom ratings, with diagnoses of affective disorder and with "other disorders," and who were enrolled in for-profit and in nonprofit plans (the mixed-effects hypothesis) produced results similar to those for the overall population, suggesting that these additional variables added little explanatory power to the overall model.

Change or stability in the difference-equivalence category of variables between time 1 (not shown) and time 2 provides a measure of whether these managed care and fee-for-service systems are becoming more alike or more different over time. Changes from time 1 to time 2 were minimal. Three of the different and not equivalent relationships at time 1 became not different and not equivalent at time 2 (depression index, medication self-pay, and hours of support services). Percentage receiving mental and physical health services changed from different but equivalent to not different but equivalent. The percentage receiving inpatient services changed from not different and not equivalent to different and not equivalent. However, the magnitude of the difference in these cases changed little from time 1 to time 2, suggesting that the change is a result of sensitivity to sample size (time 1, N=2,318; time 2, N=1,969) rather than time.

To further explore possible time effects, we examined the relationship between managed care program maturity (time from implementation of the program to first interview at each site) and variation in the patterns of difference-equivalence relationships among sites. This analysis identified a relationship for only four variables. However, two of these, rehabilitation services and inpatient detoxification, involved very few participants. Two others with more participants, MHSIP quality and penetration rate for outpatient treatment services, did vary among the sites but not according to any discernable pattern related to time since the implementation of managed care. Moreover, given the number of significance tests performed (N=34), these isolated relationships are likely due to chance.

Consistent with the perverse-incentive hypothesis, managed care programs may appear to perform better as a result of practices that limit the enrollment of participants who are likely to have higher costs or that encourage the subsequent disenrollment of these individuals. Comparative analysis of the demographic and clinical characteristics of interviewees in managed care and fee-for-service programs showed that the conditions were equivalent on most variables. This overall equivalence may indicate the absence of selective enrollment; alternatively, it may indicate the presence of selective retention. This alternative is plausible given that managed care had been operating at four of the five sites for a relatively long period when the study took place.

However, we were constrained in our ability to assess either initial selection or selective retention by this method, because very few study participants were newly enrolled in managed care, very few switched plans, and the duration of enrollment varied little overall. The fact that interviewees were similar in most respects at the time of the first interview is consistent with the panacea and equivalence hypotheses, but the similarity could as well be due to selection effects acting before the first interview, which would support the perverse-incentive hypothesis.

Discussion

Using sample survey data collected at the five study sites, we found few significant differences between managed care and fee-for-service Medicaid programs for adults with serious mental illness. On these grounds, a preliminary conclusion would be a reassuring one—that managed care apparently has no immediate and large-scale negative effects compared with fee-for-service programs on this vulnerable population; that is, the study supports the no-difference hypothesis. However, the results of the bioequivalence analysis suggest some important qualifications. Two-thirds of the no-difference findings (21 of 30) fall into the category of nonequivalence, which supports none of the managed care hypotheses—that is, the findings are simply inconclusive. (It should be noted, however, that if statistically significant differences were to be found on some measures with larger samples, these results are likely to be trivial for practical purposes—that is, they would be different but equivalent.)

Research on the impact of managed behavioral health care must address a number of conceptual and methodologic issues (45). These include heterogeneity and rapid change of plans and management techniques; heterogeneity of the fee-for services systems that often serve as a control condition; "spillover" effects from managed care to fee-for-service programs (46); uncertainty about the appropriate level of analysis (whether plans, compared with direct service providers, are sufficiently "near" to the provision of care to influence quality) (47); the confounding influence of differences in benefit packages of managed care and fee-for-service programs; and the possibility of temporal effects in managed care performance (either a longer-term negative dose effect (20) or positive organizational learning) (22) that can be captured only by a longitudinal study.

The study described here addresses some, although not all, of these issues. By employing a common protocol across multiple sites, this study lends empirical support to the suggestion that the mixed findings of previous studies as reported in research reviews are due, at least in part, to variability in system characteristics and not simply to differences in the design, methods, and reporting of individual studies. The use of a meta-analytic approach allowed for an examination of each site's relative contribution to the combined effect for each measure and, with the Q statistic, the degree of homogeneity among the plans in their contribution to that effect.

The analysis included two approaches to test for the possibility of temporal effects: a comparison of two measurement points six months apart and an examination of the effects of plan longevity. However, these analyses of time trends are only exploratory. The study's period of measurement was also too short for a thorough assessment of issues, such as the possibility of dose effects and organizational learning. In addition, the study design did not allow for assessment of spillover effects, which are likely in at least some of the sites, or of possible differences among fee-for-service systems.

The relevance of these findings depends on the extent to which current Medicaid managed care practices are consistent with those in place when the data were collected (1997-1998). Finally, the observational nature of this study, although perhaps adequate for the policy purposes it was intended to serve, does not permit the degree of certainty about the impact of managed care for persons with serious mental illness that could be achieved with random assignment of participants to the two conditions.

Conclusions

These results indicate that initiatives to enroll high-use vulnerable populations in Medicaid managed care programs exhibit no short-term, large-scale negative impacts that call for immediate policy changes. However, before any unqualified endorsement, further research that addresses limitations in the design of this study is needed. Specifically, studies with more participants, more sensitive measures, and more control over plan differences across sites are required in order to draw more definitive conclusions. More focused studies that target specific features of managed care (such as provider-level incentives to control utilization) or treatment (such as access to evidence-based practices) are needed to assess potential problem areas. Studies with a longer time frame are required to assess the possibility of long-term adverse effects, as suggested by some studies (20,48).

A second conclusion is that differences between managed care and fee-for-service programs vary from site to site, which may reflect differences among managed care plans, and perhaps fee-for-service systems as well, in characteristics, such as administrative and financial structures, benefits, and cost control and quality improvement procedures. Heterogeneity of sites is a problem confronting all multisite studies that are conducted for policy purposes, although it may be addressed to some extent by synthesizing, rather than pooling, site-level data, while controlling for site differences by means of the meta-analytic random-effects approach used here (49).

A third conclusion relates to a version of the mixed-effects hypothesis that managed care may affect vulnerable subgroups differently than the general population (50). The study reported here, which did examine this issue, produced findings comparable to those for the general population—that is, few ill effects of a scale to be detected by the measures employed here. However, this general support for the equivalence hypothesis should be considered in the context of the baseline system of mental health care for persons with serious mental illness. Fee for service was far from optimum before the introduction of managed care. Vladeck (17) observed that "The health care system has not worked very well for a long time, and at least some of the proponents of managed care have argued that they could hardly make things any worse." Learning how to use outcomes research to improve our systems of organizing and financing mental health care for vulnerable populations remains a difficult and demanding challenge.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following individuals for their substantial contributions to the Managed Care for Vulnerable Populations Study: Jackie Bianconi, M.S., Clifton Chow, Ed.M., Lori Danker, P.M.H.N.P., Jeffrey Draine, Ph.D., Julienne Giard, M.S.W., Eri Kuno, Ph.D., Jo Mahler, Virginia Mulkern, Ph.D., Jeffrey H. Nathan, Ph.D., Barbara Raab, Susan Ridgely, M.S.W., J.D., Paul Stiles, J.D., Ph.D., and Lawrence Woocher. This study was funded by grant UR7-TI11329 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Dr. Leff and Dr. Wieman are affiliated with the Human Services Research Institute, 2336 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02140 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. McFarland is with the department of psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland. Dr. Morrissey is with the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research and Dr. Stroup is with the department of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Rothbard is with the Center for Mental Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Dr. Shern and Dr. Boothroyd are with the Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute at the University of South Florida in Tampa. Dr. Wylie is with the department of psychology at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu. Dr. Allen is with Babson College in Babson Park, Massachusetts.

|

Table 1. Participants and site variables at five sites in a comparison of managed behavioral health care and fee-for-service programs under Medicaid

|

Table 2. Random-effects model group means, difference-equivalence relationship type and equivalence level, and Q statistic in a comparison of Medicaid managed behavioral health care and fee-for-service programs at five sites

1. Brach C, Sanches L, Young D, et al: Wrestling with typology: penetrating the "black box" of managed care by focusing health care system characteristics. Medical Care Research and Review 57(suppl 2):93–115,2000Medline, Google Scholar

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: National Penetration Rates From 1996–2003. Available at www.cms.hhs.gov/medicaid/managedcare/trends03.pdfGoogle Scholar

3. Mays GP, Hurley RE, Grossman JM: An empty toolbox? Changes in health plans' approaches for managing costs and care. Health Services Research 38:375–393,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Felt-Lisk S, Dodge R, McHugh M: Trends in Health Plan Serving Medicaid:2000 Data Update. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured,2001Google Scholar

5. Buck J: Medicaid, health care financing trends, and the future of state-based public mental health services. Psychiatric Services 54:969–975,2003Link, Google Scholar

6. Dickey B, Normand SL, Hermann RC, et al: Guideline recommendations for treatment of schizophrenia: the impact of managed care. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:340–348,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse services in Massachusetts. Psychiatric Services 48:1147–1152,1997Link, Google Scholar

8. Sullivan S: On the "efficiency" of managed care plans. Health Affairs 19(4):139–148,2000Google Scholar

9. Miller R, Luft H: Does managed care lead to better or worse quality of care? Health Affairs 16(5):7–25,1997Google Scholar

10. Sullivan K: Managed care plan performance since 1980: another look at 2 literature reviews. American Journal of Public Health 89:1003–1008,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rothbard A, McFarland B, Shern D, et al: Managed care for persons with serious mental illness. Drug Benefit Trends 114(2):6–14,2002Google Scholar

12. Frank R, Goldman HH, Hogan M: Medicaid and mental health: be careful what you ask for. Health Affairs 22(1):101–113,2003Google Scholar

13. Mason M, Scammon D, Huefner R: Does health status matter? Examining the experiences of the chronically ill in Medicaid managed care. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 2:53–64,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Edmunds M, Frank R, Hogan M, et al (eds): Managing Managed Care: Quality Improvement in Behavioral Health. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 1997Google Scholar

15. Mechanic D: The managed care backlash: perceptions and rhetoric in health care policy and the potential for health care reform. Milbank Quarterly 79:35–54,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Mowbray C, Grazier K, Holter M: Managed behavioral health care in the public sector: will it become the third shame of the states? Psychiatric Services 53:157–170,2002Google Scholar

17. Vladeck B: Where the action really is: Medicaid and the disabled. Health Affairs 22(1):90–100,2003Google Scholar

18. Schlesinger M, Mechanic D: Challenges for managed competition from chronic illness. Health Affairs 12(suppl):123–137,1993Google Scholar

19. Leff H, Lieberman M, Mulikern V, et al: Outcome trends for severely mentally ill persons in capitated and case managed mental health programs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:3–23,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Manning W, Lieu C, Stoner T: Outcomes for Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia under a prepaid mental health carve-out. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:442–450,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mechanic D: Managing behavioral health in Medicaid. New England Journal of Medicine 348:1914–1916,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sturm R: Cost and quality trends under managed care: is there a learning curve in behavioral health carve-out plans? Journal of Health Economics 18:593–604,1999Google Scholar

23. McCarty D: State substance abuse and mental health managed care evaluation program. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:7–17,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AF: The effect of a managed behavioral health carve-out on quality of care for Medicaid patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:442–448,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Rothbard A, Kuno E, Hadley T, et al: Psychiatric service use and cost for persons with schizophrenia in a Medicaid managed care program. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 31:1–12,2003Crossref, Google Scholar

26. DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 7:177–188,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Rogers J, Howard K, Vessey J: Using significance tests to evaluate equivalence between two experimental groups. Psychological Bulletin 113:553–565,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Ridgely MS, Mulkern V, Giard J, et al: Critical elements of public-sector managed behavioral health programs for severe mental illness in five states. Psychiatric Services 53:397–399,2002Link, Google Scholar

29. Managed Care and Vulnerable Populations: Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Core Paper 1: Sample Survey Component. Cambridge, Mass, Human Services Research Institute, 2002. Available at www.hsri.org/docs/673mcsmicore1final.docGoogle Scholar

30. Managed Care and Vulnerable Populations: Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Core Paper 2: Claims and Encounter Study Cambridge, Mass, Human Services Research Institute. 2002. Available at www.hsri.org/docs/673mcsmicore2final.doc.Google Scholar

31. Derogatis L: Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). Minneapolis, National Computer Systems, 1993Google Scholar

32. Stiles P, Boothroyd RA, Snyder K, et al: Service penetration by persons with severe mental illness: how should it be measured? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 29:198–207,2002Google Scholar

33. Mental Health Statistics Improvement Program Task Force on a Consumer-Oriented Report Card: The MHSIP Consumer-Oriented Mental Health Report Card. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1996Google Scholar

34. Toolkit on Performance Measurement Using the MHSIP Consumer-Oriented Report Card. Cambridge, Mass, Human Services Research Institute, 1998Google Scholar

35. Eisen S, Shaul J, Claridge B, et al: Development of a consumer survey for behavioral health services. Psychiatric Services 50:793–798,1999Link, Google Scholar

36. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S: A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12): construction of scales and preliminary test of reliability and validity. Medical Care 32:220–233,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

37. SPSS 11.5 for Windows. Chicago, SPSS Inc, 2003Google Scholar

38. SAS 8.0 for Windows. Research Triangle Park, NC, SAS, Inc, 2003Google Scholar

39. Iezzoni L (ed): Risk Adjustment for Measuring Healthcare Outcomes, 3rd ed. Chicago, Health Administration Press, 2003Google Scholar

40. Banks S, McHugo GJ, Williams V, et al: A prospective meta-analytic approach in a multisite study of homelessness prevention. New Directions for Evaluation, no 94:45–59,2002Google Scholar

41. Cocozza JJ, Jackson EW, Hennigan K, et al: Outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma: program-level effects. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 28:109–119,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Lipsey M, Wilson D: Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2001Google Scholar

43. Hargreaves WA, Shumway M, Hu T-W, et al: Cost-Outcome Methods for Mental Health. San Diego, Academic Press, 1998Google Scholar

44. Stegner B, Bostrom A, Greenfield T: Equivalence testing for use in psychosocial and services research: an introduction with examples. Evaluation and Program Planning 19:193–198,1996Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Luft H: Measuring quality in modern managed care. Health Services Research 38:1373–1384,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Federman A, Siu A: The challenge of studying the effects of managed care as managed care evolves. Health Services Research 39:7–12,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Lozano P, Grothaus LC, Finkelstein JA, et al: Variability in asthma care and services for low-income populations among practice sites in managed Medicaid systems. Health Services Research 38:1563–1578,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Morrissey JP, Stroup TS, Ellis AR, et al: Service use and health status of persons with severe mental illness in full-risk and no-risk Medicaid programs. Psychiatric Services 53:293–298,2002Link, Google Scholar

49. Straw R, Herrel J: A framework for understanding and improving multi-site evaluations. New Directions for Evaluation, no 94:5–15,2002Google Scholar

50. Wooldridge J, Hoag SD: Perils of pioneering: monitoring Medicaid managed care. Health Care Financing Review 22:61–83,2000Medline, Google Scholar