Service Use and Costs for Women With Co-occurring Mental and Substance Use Disorders and a History of Violence

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study examined the 12-month cost of the array of services used by women with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders and a history of violence and trauma who participated in the Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Study (WCDVS). The study compared costs of the intervention and external services for women in the WCDVS intervention in outpatient and residential settings—which provided comprehensive, integrated, and trauma-informed services—with the costs for women in the usual-care comparison group. The study also compared costs with recorded clinical outcomes. METHODS: Costs of service use were examined for 2,026 women who participated in the WCDVS (N=1,018) and in the comparison group (N=1,008). Women were interviewed three, six, nine, and 12 months after baseline about any service use in the past three months. Costs for these services, along with indirect costs (participants' time and transportation) were estimated by using a variety of sources. A number of cost estimates were analyzed by using either ordinary least squares regression or two-part models. RESULTS: The average participant had almost $43,000 in costs related to their service use during the 12 months after baseline. Women in the intervention group had lower service costs and higher overall costs than those in the comparison group, but the null hypotheses of no difference in any cost measure between groups was not rejected. Also, the null hypothesis of no difference in the probability of accessing services external to the study intervention was not rejected. CONCLUSIONS: Because no differences were detected in costs but improvements were seen in clinical outcomes, the interventions offered in the WCDVS may be more efficient than usual care.

Violence is widespread in the lives of women who receive services through publicly funded service systems in the United States. Studies recruiting samples from different service settings show extremely high lifetime prevalence rates of physical and sexual abuse. Lifetime physical or sexual abuse has been reported by 50 to 70 percent of women in psychiatric inpatient units (1), 70 percent of women in psychiatric emergency departments (2), and 51 percent of women in outpatient mental health clinics (3). Similarly, between 55 and 99 percent of women with substance use disorders have reported being victimized at some point in their lives (4,5). The combination of traumatic victimization with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders leads to a particularly complex clinical picture. Women facing all three of these issues are likely to have more severe difficulties and to use services more often than women with any one of these problems (6,7,8).

Current service delivery systems are often inadequate and inefficient in treating this population of women (6,9,10). Limited screening for trauma, a lack of available trauma services, extremely fragmented or siloed services that fail to comprehensively address these issues, and a lack of cross-training among services for violence and mental health and substance use disorders are significant barriers to women's recovery (11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18).

In the absence of effective services, many women continue a cycle of repeated ineffective treatment attempts, which negatively affects their well-being and is economically costly to society. Increasing national attention has been focused on the needs of women with co-occurring disorders and a history of trauma (19). The Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Study (WCDVS) was designed to test a comprehensive, integrated service approach to serving women with co-occurring disorders and a history of violence and trauma and to determine whether such an approach can lead to more efficient service use and, therefore, more efficient use of public resources. Research has begun to address the effectiveness of service interventions (20,21,22) as well as the efficiency and costs of providing services to meet these needs (23,24).

Efficiency arguments have long appeared in research on health services and are especially relevant in investigations of treatments for populations with severe or comorbid conditions. If resources can be reallocated to either obtain more health improvements for the same level of resource use or lower costs for the same level of health, an intervention is said to be more efficient than its alternative.

Examining resource use in populations with comorbid mental health and substance use disorders becomes an important and especially difficult proposition because of the great variety of service systems used, including traditional medical care, case management, mental health and substance use services, homeless and domestic violence shelters, and even jails. Few studies have been able to look across these service systems at the use and costs of services for persons with service use in multiple systems. Interventions targeted at persons who use multiple service systems must anticipate spillover effects, or effects on the use of services outside the system in which the intervention is delivered.

The purpose of the study presented here was threefold. First the study examined the total 12-month cost of services use by women with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders who have a history of violence and trauma and participated in the WCDVS. Second, it examined the cost difference between the WCDVS intervention and usual care. Finally, the study compared these incremental costs with the clinical outcomes reported previously (21,22). A rich data set on service use from a wide array of sectors allowed us to calculate the costs related to service use in a variety of settings. We examined the total costs of service use across service systems and also analyzed services, such as hospital or jail use, that are clearly external to the study intervention.

Previous work showed that in the first six months of the study the costs of service use from both a Medicaid and an all-government perspective were quite similar for persons in both study groups (24). In this study we examined the societal costs of service use during the full 12-month study period. We examined specifically the types of services used and estimated the cost for each type of service. This analysis is important not only in understanding how the intervention affected the use of services but also in understanding the types of services used in the usual-care group. Others have pointed out that despite the large number of clinical and research trials that use a usual-care control group, the composition of services received in usual care is understudied (25).

Methods

Study sample

The WCDVS was a five-year project funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to produce empirical knowledge about the development and effectiveness of comprehensive, integrated services for women with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders who have experienced trauma (26). During the first phase of the project, which lasted two years, a coordinating center and 14 U.S. sites were funded to develop service interventions that were comprehensive, integrated, and trauma informed and that integrated consumers into the work of the project. Nine of these sites were funded for the second, three-year phase of the project. During the second phase the nine sites participated in a multisite outcome study that used a quasi-experimental design in which each site was paired with a comparison agency or agencies in their geographic area that provided usual services for this population. The study period was from January 11, 2001, to March 29, 2003.

Study participants were recruited through an informed-consent process from substance abuse or mental health treatment programs, peer-led programs, or domestic violence shelters or by word of mouth. The study protocol was approved by the local institutional review board at each study site and at the coordinating center. Participants had to be aged 18 or older, have substance abuse and mental health diagnoses (at least one current and the other within the past five years), have received services for substance abuse or mental health issues on at least two previous occasions, and have experienced physical or sexual abuse.

Participants

Women enrolled in the study had repeated addiction treatment episodes, a mean of 3.7 and 5.6 times for alcohol abuse and drug abuse, respectively. Forty-nine percent had experienced a psychiatric hospitalization and had been previously hospitalized for psychiatric treatment, averaging 4.5 times (27). Women in the sample were relatively young, with a mean age of 36 years. Only two-thirds (68.5 percent) reported that they had current health insurance coverage, primarily from enrollment in a state Medicaid program.

Exactly half (50.0 percent) of the women identified themselves as non-Hispanic/Latino white, and a substantial minority identified themselves as non-Hispanic/Latino African American/black or Hispanic/Latino. Other groups that were sampled included American Indian, Asian, and multiple races or ethnicities. At baseline participants in the intervention group had higher severity on some mental health and substance abuse measures than those in the comparison group (22).

Interventions

Although study sites were required to field interventions that were comprehensive, integrated, and trauma informed and that integrated services, there was some variability in the interventions used. All the interventions included two core services: first, a psychoeducational group counseling curriculum that provided integrated counseling for trauma, mental health, and substance abuse; second, resource coordination and advocacy provided through case managers, peer aides, or integrated treatment teams.

The outcome analyses found that the sites that demonstrated a significant difference between the intervention and comparison groups in the percentage of women who reported receiving integrated counseling that specifically addressed mental health, substance abuse, and trauma (high-contrast sites) had a greater level of improvement in mental health and trauma outcomes than the sites that did not show this difference (low-contrast sites) (20,21,22). That is, each of the nine sites was labeled as a high-contrast site if participants in the intervention group were significantly more likely to report having received trauma-informed services than participants in their comparison group during the first three months of the intervention. We conducted separate cost analyses with this distinction to determine whether these clinical improvements came at a greater cost. At six months, we found greater service costs for these high-contrast sites (24).

Service use data

Study participants were interviewed by using standardized cross-site protocols when they first entered treatment and three, six, nine, and 12 months thereafter. A total of 2,729 baseline interviews were completed across the nine sites. Of these women enrolled in the study, 2,026 (74.2 percent) were successfully interviewed at their 12-month follow-up within a 12-week window from the anticipated date and were used in the analysis presented here—1,018 in the WCDVS and 1,008 in the comparison group.

We did not find evidence that the factors that were associated with attrition from the study were different between the two study groups, and no difference in dropout rates between groups was detected at each of the nine study sites. None of the baseline clinical measures was significant in predicting study attrition, nor was pre-baseline cost. Only site identifiers or fixed effects and younger age predicted dropout in this analysis. At each time point (three, six, nine, and 12 months after baseline) participants were asked to report on their service use during the previous three months or since their last complete assessment; services received from the study sites and services received outside the study setting are reported and are not distinguished from each other.

Questions about service use covered a range of services, including hospital and detoxification facility inpatient visits, emergency department visits, residential substance abuse treatment, shelter stays, individual and group counseling, case management, medical visits, peer support groups, and time in jail (arguably a service). The amount of each service received was quantified by asking respondents to report the frequency and average duration of their service contacts. Annual service use summed up all services reported in the four postbaseline assessments.

Cost estimation

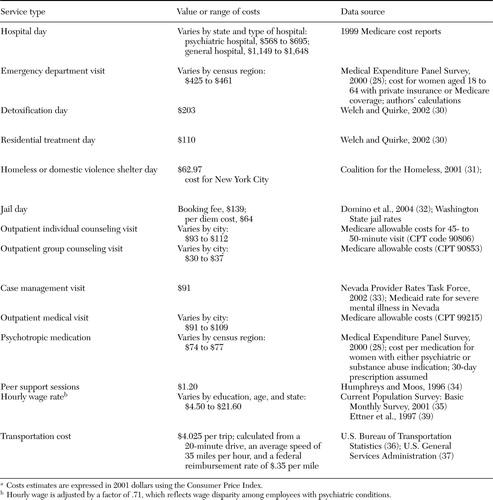

As shown in Table 1, we assigned unit costs to the self-reported services by using a variety of sources. We used estimates of the average payment for each service unit whenever possible. Regional differences were used in unit costs when available, but the same price weights were used for the intervention and comparison sites within each region or state.

Some average costs per unit of service are from federal data sources, including the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data, a representative sample of the medical use and expenditures of persons in the United States (28) and the Medicare fees and hospital cost reports. For all other types of service use we relied on estimates available in the literature, updated to the current period for inflation (29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37). The product of unit cost times the number of units of service reported for each service type yields the total cost of services for each woman in the sample.

Because costs of services capture only the opportunity costs of provider time and capital, we also calculated the time costs of receiving services for the participants. Explicitly valuing the time women spent while receiving services during the study period gets us closer to a societal cost perspective, which is recommended for economic evaluations (38,39).

We quantified time costs as follows. Because information on wage was not available for most study participants, we assigned an expected wage to each study participant, whether actually employed or not. Expected wages were calculated from the 2001 monthly U.S. Current Population Survey for women aged 18 and older, from averages for each unique combination of state, education level, and age group. Because persons with mental illnesses have been noted to receive wages that are 29 percent lower than their counterparts without mental illness (39), we deflated the average wages by this factor, and then assigned the average adjusted wage to each participant according to her state, educational level, and age group.

Time costs were calculated as the total time in treatment and transportation multiplied by the expected wage. The time spent receiving outpatient services was reported on the survey instrument, and we used an estimated time of 16 hours per day for the use of inpatient hospital, residential, detoxification, and jail services, following the methods in a study by Simon and colleagues (40), and four hours per day for emergency department use. We added 20 minutes each way for travel time for all services and developed an estimate of transportation costs as well (Table 1). Costs of services, time, and transportation are summed together as overall costs. All costs are expressed in 2001 dollars.

Clinical outcomes

Four dimensions of clinical functioning were measured at each assessment period: severity of drug use, severity of alcohol use, mental health status, and trauma symptoms. These dimensions were assessed with the Addiction Severity Index drug composite score (ASI-D), the Addiction Severity Index alcohol composite score (ASI-A), the Global Severity Index (GSI) from the Brief Symptom Inventory, and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale (PSS), respectively. The reporting period for the ASI-D, the ASI-A, and the PSS was during the past month. The reporting period for the GSI was during the past seven days. For the analyses presented here, the 12-month assessments of these measures were used as clinical outcome variables. Higher scores on all the indices indicate greater severity (27).

Analyses

We used ordinary least squares regression with an independent variable that indicated whether each participant was in an intervention group. Dependent variables for this analysis included service costs and overall costs. We used the untransformed version of the cost variables for all analyses because the results of a Wooldridge test (41) indicated that this form fit the data better than a log transformation. We controlled for differences in the levels of use in the three months before baseline in the models. Although this lagged dependent variable is not usually a desired inclusion in a regression model because of the high level of potential endogeneity, we did not have a better instrument for the differences in services use that were observed at baseline in this nonrandomized sample. We reran the main models without this lagged term entirely and with substituted baseline clinical measures and obtained virtually identical results. We also included participants' age and site fixed effects, which controlled for the heterogeneity in intervention and comparison services at each study site and for differences in the overall cost of living and other forms of unobserved site-specific heterogeneity. Standard errors were adjusted for clustering at the site level.

In addition to the basic model, we examined whether participation in the intervention was associated with a change in costs that were purely external to the intervention. Because the total measure of costs includes services that we expected to see the intervention group use more often (for example, outpatient group counseling visits) as well as those we would expect to decrease with a successful intervention (for example, jail), we examined costs for external services separately as an outcome measure. Because not all women used external services, we used two-part models to examine both the likelihood of using some type of external service as well as the level of use for persons who used external services, measured both by service and overall costs.

Because of the nonrandom assignment to study conditions and the observed differences between women in the two groups, we conducted a propensity score analysis to determine whether the results were robust to various subgroups of participants that are more similar on the basis of their baseline characteristics. For this analysis, we ran a first-stage regression modeling study arm assignment (intervention) as a function of the observable baseline characteristics. We then split the predicted value of this variable into quintiles and separately ran the regression models for each quintile.

We generated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for each of the four clinical outcomes measured in the study (22). These ratios, which express the expected incremental cost of intervention services over services for the comparison group per unit improvement in each clinical score, are calculated as the ratio of the coefficient on the intervention indicator from separate regressions on costs and clinical outcomes. Bootstrapped 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs) are also presented.

Results

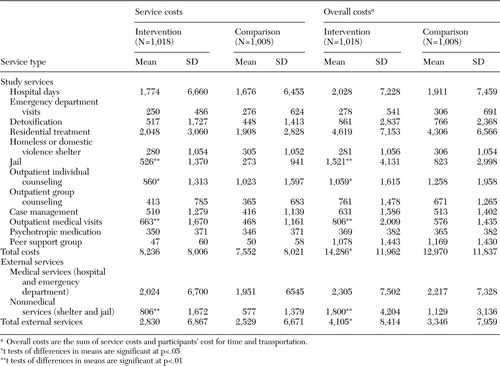

As shown in Table 2, the average woman in the study used just under $8,000 in services in the three months before entering the study. This high level of use is a validation that the study successfully recruited its target group of high-end service users (26). Levels of use by type of service were quite similar between study arms; statistically significant differences were found only in jail, outpatient medical service use, and individual outpatient counseling. The average prebaseline service costs and overall costs were somewhat higher for women in the intervention group, but the difference in service costs was just short of conventional statistical significance. The larger difference in overall costs indicates that the time cost of service use was higher for women in the intervention group before baseline.

Because no differences were detected in the wage rate between women in the two groups, the difference in overall costs must be from the time spent using services. Women in the intervention group had overall external costs at baseline that were almost $800 higher than those in the usual-care group. External services were further broken down into external medical services (hospital and emergency department) and external nonmedical services (jail and shelter). Only external nonmedical service costs were higher for women in the intervention group during the three months before baseline.

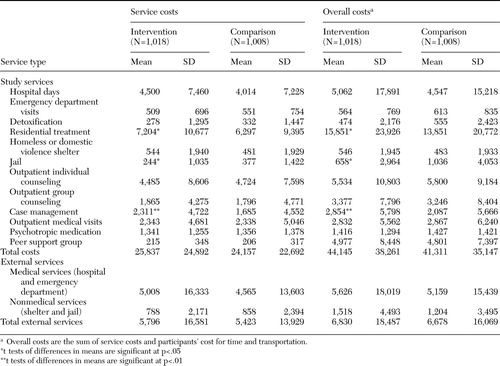

As shown in Table 3, we next examined the costs, unadjusted for covariates, of the same service categories during the 12-month study period. Differences were found in service costs and overall costs for three different service areas: women in the intervention group had higher costs for residential and case management services and lower jail costs. No other statistically significant difference was detected in unadjusted costs, including total and external cost measures.

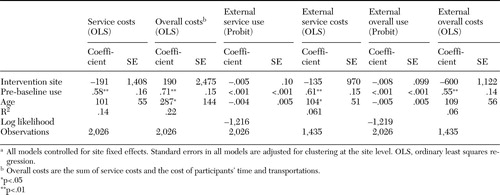

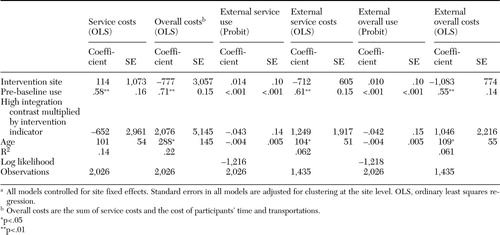

When differences in service costs and overall costs were examined in regressions that controlled for differences in baseline levels of use, we found that women in the intervention group had lower average service costs and higher overall costs; however, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 4). We did not find any difference between the groups in the probability of obtaining external services. We found a lower level of average costs of service use for women who reported using any external services in the intervention group, but this difference was not statistically significant for either cost measure. Although the purpose of this analysis was to examine the overall trends in costs across study sites, we also repeated the analyses at the study site level. We found significant cost differences between the two groups at some of the sites, but a majority of sites showed no difference for each cost measure.

As shown in Table 5, in contrast with our findings at six months (24), we found no statistically significant difference between the intervention costs at high-contrast sites and those at low-contrast sites. However, for the six-month findings we assessed only the costs of services used, whereas the analysis presented here included time and travel costs for participants.

The propensity score analysis results support the original findings in that no cost differences were detected in any of the cost measures reported in Table 4 by each propensity group. However, there was one exception: we found substantially lower (-$5,240; p<.05) service costs for women in the intervention group for the third propensity quintile.

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios and their bootstrapped CIs are problem severity of drug use (ASI-D), $12,227 (CI=-$210,578 to $235,286); problem severity of alcohol use (ASI-A), $9,996 (CI=-$292,287 to $362,459); mental health symptoms (GSI), $1,814 (CI=-$37,693 to $35,903); and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (PSS), $123 (CI=-$2,584 to $2,547). Because virtually all (more than 99 percent) of the bootstrapped simulations reflected a negative incremental outcome score, indicating clinical improvement, the fact that the CIs contain zero means that we cannot rule out the hypotheses of either greater incremental costs or potential cost savings associated with the improved clinical outcomes from intervention services.

Discussion

Coupled with the findings on clinical outcomes (22), the results reported here indicate that it is likely that the interventions offered in the WCDVS reallocated the same level of total resource use for services in a more efficient manner, which improved clinical outcomes, albeit modestly. We did not find any evidence that the total overall costs of service use were greater for women in the intervention arm than they were in the comparison arm. These costs are not insubstantial. The average study participant had almost $43,000 in costs related to their service use during the 12-month postbaseline period. These costs are incurred in a variety of service systems, such as mental health, substance abuse, and medical treatment settings, as well as the criminal justice system. In addition, the indirect costs, defined here as time and transportation costs, were not inconsequential, totaling more than a third of the overall costs.

The lack of a difference in the service-related costs between the two study arms may have several explanations. The participants in the study were high users of the service system in the prebaseline period. It may be the case that the patterns of treatment seeking were well established by these women and not easily affected by an intervention such as the one examined here. The total cost measure also masks differences by types of services. For example, in contrast with women in the comparison group, women in the intervention group had higher average jail costs at baseline but lower average jail costs at the 12-month follow-up. This shift suggests that the intervention may be associated with reduced jail costs for the participating women. This finding is consistent with results reported by Daley and colleagues (42), who found that a reduction in costs to the jail sector was associated with the receipt of a residential substance abuse treatment program by a cohort of pregnant women. These service-level differences may cancel each other out in the aggregate.

For policy makers interested in considering the unadjusted findings at the service use level (Table 3), the public policy challenge will be how to shift funds from one sector (jail or emergency shelter) to another (health care services). Different levels of government and different public programs pay for these various activities and cannot easily be programmatically or legislatively shifted from one sector to another. Thus the intervention models that result in greater use of health care services among participants will require additional health care funding during a period when the public system is under pressure to reduce overall costs.

Nearly all these service models incorporated service elements that are not currently reimbursable by public payers and thus may be difficult to translate to new locations without demonstration programs such as the WCDVS. Among the many elements incorporated in these trauma-informed interventions were peer-run groups, consumer training, extended case management, interdisciplinary team meetings, cross-training of providers, and additional screening and assessment for trauma and mental health problems. Under most Medicaid models and other reimbursement mechanisms, it would be a challenge to find a sustainable source of funds for these activities.

We did examine separately the costs of service use that are completely outside the package of services required by the intervention models. These external service measures can be thought of as an outcome variable, because we hypothesized that women in the intervention group would have higher levels of use of the types of services offered by the intervention but, if effectively treated, lower rates of use for other services, such as hospitals, shelters, and jails. We did not find any evidence of a difference in the levels of external services use. Although 12 months is a fairly long follow-up period in a prospective study, it may not have been long enough to capture an effect of the intervention.

On the basis of previous cost analyses (42,43,44,45) we had hypothesized that programs that successfully reduce substance use and mental health symptoms among clients with complex and high-end service needs would indeed result in less hospitalization, crisis services, and services associated with criminal justice. Thus it is disappointing that this study did not find evidence of external cost savings. We cannot rule out the idea that some site interventions may have been cost saving, even though overall the WCDVS was not.

Results from the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio calculations generated a wide confidence interval around zero. Consistently across measures, we found that 46 percent of the bootstrap replications predict a cost saving, clinically improved outcome, which would indicate that the intervention service model performs better than the usual-care model. The remaining 54 percent of the replications indicate that the clinical improvements come at some cost. The near equivalency of the fraction of the replications confirms the earlier result of no consistent cost difference between the two study arms. Whether the cost per unit improvement is comparable to other interventions or in an acceptable range would require further work beyond the scope of this study to translate the four clinical measures used here into quality-adjusted life year (QALY) terms, a common metric used in the literature. To our knowledge no other cost-effectiveness analyses have been conducted in a similar population with similar outcome measures.

Several limitations of the analysis should be noted. The quasi-experimental design means that there may have been unobservable differences between women in the two study arms. Baseline analyses suggest that women in the intervention arm may have been slightly more severely ill (26). This difference is reflected in the prebaseline overall cost measure used in the regression models. Service use measures are self-reported and thus likely suffer from recall bias, although the short recall period of three months that was used in this study should minimize this effect. Measurement error from recall bias in the dependent variable will not bias the results unless the measurement error is correlated with the explanatory variables.

No effort was made in this analysis to distinguish reporting of services received as a part of the study intervention from services received in other contexts or even at other agencies or clinics. We tend to think of this approach positively in that service use outside of the intervention model is one of the features that may distinguish an efficacy study from an effectiveness study. However, we are not able to say anything either about the amount of treatment received by the study participants or about the agency-level costs to implement such an intervention.

Although the interventions may have differed in the types of personnel, training of personnel, and setting of care, the same unit costs were used for both the intervention and comparison arms, which implicitly assumes the same level of intensity of service across study arms. If the trauma-informed content of the intervention services would result in a higher unit cost, our methods would bias the estimate of a cost difference toward the null.

These unit costs, or price weights, should be interpreted as steady-state prices, rather than start-up costs, which were not analyzed here but were examined in a separate analysis of a subset of intervention sites (23), because it is likely that intervention sites incurred greater start-up costs than comparison sites. Other costs were not included because of data limitations, including costs related to the time of caregivers, spouses, or partners and to child care expenses related to service receipt.

An additional important policy question would be to project the costs of replicating these trauma-informed service delivery approaches in other programs. In this study new or additional services delivered by the intervention sites and the incremental costs of integrating care delivery—such as training existing service providers and holding interdisciplinary service team meetings—were not separately studied. Again, because each site used a different approach in enhancing services, it is likely that a range of incremental costs were associated with the adaptation of existing program models to a trauma-informed system. For example, one site developed a mechanism to link women in the intervention to the services of a psychiatrist. However in this study these services would be included as an individual counseling session with the same average cost of counseling services from caseworkers, social workers, and other less costly providers.

Further work is needed to confirm these findings. A randomized trial of the intervention service models would be an important next step. Such a trial could be conducted among high-end system users, such as persons in this sample, and among persons who are less engaged in one or more service systems. Self-reports of services use could be complemented with administrative claims data from Medicaid programs or private insurance plans to further clarify the effect of the intervention on health service expenditures for these or other payers. Other costs, such as caregiver time and costs related to child care as a result of receipt of services should be included. Clinical outcome measures could be combined into a unidimensional QALY measure to facilitate cost-effectiveness comparisons with other interventions targeted at this population, although other authors have noted that the nature of substance abuse symptoms necessitates a multidimensional measure (46).

Conclusions

The interventions offered in the WCDVS appear to be more efficient than usual care, because no differences were detected on average in costs but improvements were seen in clinical outcomes. However, CIs around cost-effectiveness ratios were broad, indicating a fair amount of variability in this result. Reported cost-effectiveness ratios should be compared with future interventions in this population.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the guidance for applicants grant, number TI-00-003, from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's three centers: the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, the Center for Mental Health Services, and the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. This grant was entitled cooperative agreement to study women with alcohol, drug abuse and mental health disorders who have histories of violence: Phase II. Additional support was received by Dr. Domino from grant K01-MH-0656-39 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Domino, Dr. Morrissey, and Ms. Chung are affiliated with the department of health policy and administration at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Morrissey is also with the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the university. Mr. Huntington is with the National Center on Family Homelessness in Newton, Massachusetts. Dr. Larson is with the Institute for Health Services Research and Policy in Watertown, Massachusetts. Dr. Russell is with ETR Associates in Scotts Valley, California. Send correspondence to Dr. Domino at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Health Policy and Administration, Campus Box 7411, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7411 (e-mail, [email protected]). This is the second of three papers in this issue reporting results from the Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Study funded by SAMHSA.

|

Table 1. Estimation of unit costs for services received by participants in the Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Studya

aCosts estimates are expressed in 2001 dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

|

Table 2. Average service costs and overall costs (in dollars) among participants in the Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Study in the three months before baseline

|

Table 3. Unadjusted cumulative 12-month average service costs and overall costs (in dollars) among participants in the Women, Co-occurring Disorders, and Violence Study

|

Table 4. Regression analysis of the effect of the Women Co-occurring Disorders and Violence Study intervention on 12-month total costsa

aAll models controlled for site fixed effects. Standard errors in all models are adjusted for clustering at the site level. OLS, ordinary least squares regression.

|

Table 5. Regression analysis of the effect of the Women Co-occurring Disorders and Violence Study intervention on 12-month total costs, while controlling for the high-contrast integration modelsa

aAll models controlled for site fixed effects. Standard errors in all models are adjusted for clustering at the site level. OLS, ordinary least squares regression.

1. Carmen EH: Inner city community mental health: the interplay of abuse and race in chronic mentally ill women, in Mental Health, Racism, and Sexism. Edited by Willie CV, Rieker PP, Kramer BM, et al. Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh University Press, 1995Google Scholar

2. Briere J, Zaidi LY: Sexual abuse histories and sequelae in female psychiatric emergency room patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1603–1606,1989Google Scholar

3. Muenzenmaier K, Meyer I, Struening E, et al: Childhood abuse and neglect among women outpatients with chronic mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:666–670,1993Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw SR: The link between substance abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder in women: a research review. American Journal on Addictions 6:273–283,1997Medline, Google Scholar

5. Miller BA, Downs WR, Testa M: Interrelationships between victimization experiences and women's alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement 11:109–117,1993Medline, Google Scholar

6. Harris M: Modifications in service delivery and clinical treatment for women diagnosed with severe mental illness who are also the survivors of sexual abuse trauma. Journal of Mental Health Administration Special Issue: Women's Mental Health Services 21:397–406,1994Google Scholar

7. Brown V, Huba G, Melchior L: Level of burden: women with more than one co-occurring disorder. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 27:339–346,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Liebschutz JM, Mulvey KP, Samet JH: Victimization among substance abusing women: worse health outcomes. Archives of General Medicine 157:1093–1097,1997Google Scholar

9. Bergman B, Brismar B: A 5-year follow-up of 117 battered women. American Journal of Public Health 81:1486–1489,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Koss MP, Koss PG, Woodruff WJ: Deleterious effects of criminal victimization on women's health and medical utilization. Archives of Internal Medicine 151:342–347,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. McCauley J, Kern DE, Kolodner K, et al: The "battering syndrome": prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Annals of Internal Medicine 123:737–746,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Violence Against Women in the United States: A Comprehensive Background Paper. New York, Commonwealth Fund, 1996Google Scholar

13. Harris M, Fallot RD: Envisioning a trauma-informed service system: a vital paradigm shift, in Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems: New Directions for Mental Health Services: Vol 89. Edited by Harris M, Fallot RD. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2001Google Scholar

14. Fallot RD, Harris M: A trauma-informed approach to screening and assessment, in Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems: New Directions for Mental Health Services: Vol 89. Edited by Harris M, Fallot RD. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2001Google Scholar

15. Mueser KT, Hiday VA, Goodman LA, et al: People with mental and physical disabilities, in Trauma Interventions in War and Peace: Prevention, Practice, and Policy. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2003Google Scholar

16. Grella CE: Background and overview of mental health and substance abuse treatment systems: meeting the needs of women who are pregnant and parenting. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 28:319–343,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ridgely MS, Goldman HH, Willenbring M: Barriers to the care of persons with dual diagnoses: organizational and financing issues. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:123–132,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Zweben JE: Psychiatric problems among alcohol and other drug dependent women. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 28:345–366,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Ouimette P, Brown PJ: Trauma and Substance Abuse: Causes, Consequences, and Treatment of Comorbid Disorders. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association Press, 2002Google Scholar

20. Cocozza JJ, Jackson EW, Hennigan K, et al: Outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma: program-level effects. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 28:109–119,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Morrissey JP, Ellis AR, Gatz M, et al: Outcomes for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma: program and person-level effects. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 28:121–133,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Morrissey JP, Jackson EW, Ellis AR, et al: Twelve-month outcomes of trauma-informed interventions for women with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatric Services 56:1213–1222,2005Link, Google Scholar

23. Dalton K, Domino ME, Nadlicki T, et al: Developing capacity for integrated trauma-related behavioral health services for women: start-up costs from five community sites. Women and Health 38:111–126,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Domino M, Morrissey JP, Nadlicki-Patterson T, et al: Service costs for women with co-occurring disorders and trauma. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 28:135–143,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Horvitz-Lennon M, Normand SLT, Frank RG, et al: "Usual care" for major depression in the 1990s: characteristics and expert-estimated outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:720–726,2003Link, Google Scholar

26. McHugo G, Kammerer N, Jackson EW, et al: Women, Co-occurring Disorders and Violence Study: evaluation design and study population. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 28:91–107,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Larson MJ, Miller L, Becker M, et al: Physical health burdens of women with trauma histories and co-occurring substance abuse and mental disorders. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 32:128–140,2005Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: Data and Publications. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at www.meps.ahrq.gov/data_public.htmGoogle Scholar

29. Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Garber AM, et al: Productivity costs, time costs, and health-related quality of life: a response to the Erasmus Group. Health Economics 6:505–510,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Welch K, Quirke M: Wisconsin Substance Abuse Treatment Capacity Analysis:2000. Madison, Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin Center for Health Policy and Program Evaluation,2002Google Scholar

31. Rental Assistance for Working Homeless New Yorkers: A Cost-Effective Way to Reduce Shelter Capacity and Save Taxpayer Dollars: 2001. Coalition for the Homeless. Available at www.coalitionforthehomless.org/dowloads/rntalassistbriefpap2001.pdfGoogle Scholar

32. Domino ME, Norton EC, Morrissey JP, et al: Cost shifting to jails after a change to managed mental health care. Health Services Research 39:1379–1401,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Determining the Strategy for Providing and Reimbursing Case Management in Nevada. Nevada Provider Rates Task Force. Aug 15, 2002. Available at http://hr.state.nv.us/shcp/documents/rates_documents/tcm-report-081502.pdfGoogle Scholar

34. Humphreys K, Moos RH: Reduced substance-abuse-related health care costs among voluntary participants in Alcoholics Anonymous. Psychiatric Services 47:709–713,1996Link, Google Scholar

35. Current Population Survey: Basic Monthly Survey: 2001. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bureau of the Census. Available at www.bls.census.gov/cps/bdata.htmGoogle Scholar

36. Transportation Statistics: Annual Report: 1994. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, US Department of Transportation. Available at www.bts.gov/publications/tranportation_statistics_annual_report/1994/pdf/report.pdfGoogle Scholar

37. Privately Owned Vehicle Reimbursement Rates. US General Services Administration. Available at www.gsa.gov/Portal/gsa/ep/contentView.do?contentType=GSA_BASICandcontentId=9646Google Scholar

38. Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Edited by Gold MR, Gold SR, Weinstein WC. Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

39. Ettner SL, Frank RG, Kessler RC, et al: The impact of psychiatric disorders on labor market outcomes. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 51:64–81,1997Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Simon GE, Manning WG, Katzelnick DJ, et al: Cost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment for high utilizers of general medical care. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:181–187,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Wooldridge JM: A simple specification test for the predictive ability of transformation models. Review of Economics and Statistics 76:59–65,1994Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Daley M, Argeriou M, McCarty D, et al: The costs of crime and the benefits of substance abuse treatment for pregnant women. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 19:445–458,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Gerstein DR, Johnson RA, Harwood H, et al: Evaluating Recovery Services: The California Drug and Alcohol Treatment Assessment (CALDATA). Contract no 92–00110. Sacramento, Calif State of California, Health and Welfare Agency, Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs, 1994Google Scholar

44. Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, et al: Cost-effectiveness evaluation of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill clients. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:341–348,1997Link, Google Scholar

45. Culhane D, Metraux S, Hadley T: Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless persons with severe mental illness. Supportive Housing Policy Debate 13:107–163,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

46. Sindelar JL, Jofre-Bonet M, French MT, et al: Cost-effectiveness analysis of addiction treatment: paradoxes of multiple outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 73:41–50,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar