Race, Urban Community Stressors, and Behavioral and Emotional Problems of Children With Special Health Care Needs

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study examined the relationship of community-level stressors to behavioral and emotional problems among African-American and white children with special health care needs. METHODS: The authors interviewed 257 low-income caregivers of children with special health care needs in an urban Midwestern city who brought their child for a primary health care visit to a community health center between September 2001 and May 2002. Sociodemographic characteristics as well as information about the children's behavioral and emotional problems, the health status of the children, perceptions of urban community stress, access to health care, and satisfaction with health care were collected to determine racial differences in the impact of urban stress on behavioral and emotional problems. RESULTS: Urban community stressors, race, and child's health status were significantly associated with behavioral and emotional problems among children with special health care needs. The association between urban stress and total behavioral problems did not differ by race. CONCLUSIONS: When caring for children with special health care needs, especially those with emotional or behavioral problems, primary care providers may be better able to identify important aggravating factors if they also assess urban stress. Systems of care are needed that can assist in addressing urban community-level stressors.

Children with special health care needs have behavioral and emotional problems at much higher rates than other children (1,2,3,4,5). Children with special health care needs are "those who have or are at increased risk of a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally" (6,7). Despite having a greater need for mental health services, these children face significant barriers to such care and often do not receive needed mental health services (1). Community-level contextual stressors, such as poverty, unemployment, crime, and lack of social support, have been associated with both an increased incidence of behavioral and emotional problems and inadequate mental health care (2,3), but their impact on the mental health of low-income children with special health care needs is poorly understood.

Several studies have examined the impact of community-level contextual stressors on behavioral and emotional problems of children and adolescents (8,9,10,11). Community-level contextual stressors act as important mediators in the relationship between sociodemographic factors and mental health problems (12). Among a sample of Midwestern, inner-city, elementary-school children, stressful life events and neighborhood disadvantage were independently associated with behavioral problems (13). Economic stress has been associated with troubled family relationships, and these difficult family interactions can have a negative impact on the mental health of children (14,15). In addition to experiencing more mental health problems, children from low-income families are less likely to obtain mental health services (16).

Because children from minority groups are more likely to experience persistent poverty and neighborhood disadvantage (17), it is important to also consider racial differences in the effect of community-level contextual stressors on children's mental health. Numerous studies have shown that even when socioeconomic status is controlled for, African Americans, compared with whites, live in neighborhoods with higher levels of poverty, crime, and substance abuse (18,19,20,21). Furthermore, spatial inequality contributes to a lack of social capital for children from racial or ethnic minority groups, because these children are more likely to live in neighborhoods that are deficient on measures of adult-child exchange and social control (22).

In the study reported here we examined sociodemographic characteristics, health status, access to health care, satisfaction with health care, and community-level contextual stressors that might influence behavioral and emotional problems among African-American and white low-income children with special health care needs. Our study contributes to the field of inquiry regarding community-level contextual stressors and behavioral and emotional problems among children with special health care needs in several ways. First, we describe the behavioral and emotional problems in a sample of Midwestern, urban, low-income children with special health care needs. Second, we extend the validation of a contemporary subjective measure of contextual stressors in urban communities, the Urban Life Stressor Scale (ULSS) (23). Contextual measures such as the ULSS have been underused in studying pediatric populations and virtually unused in studying children with special health care needs. Finally, we examine racial differences in the relationship of community-level contextual stressors to behavioral and emotional problems, controlling for demographic and health care access and satisfaction factors.

Our analysis was guided by the following questions. First, are there racial differences in demographic characteristics, health status, access to health care, satisfaction with health care, and community-level contextual stressors among urban low-income children with special health care needs? Second, how are these variables associated with the presence of behavioral and emotional problems among these children? Third, are there racial differences in the association of urban stress and behavioral and emotional problems of these children when demographic variables, health status, access to health care, and health care satisfaction are controlled for?

Methods

Sample

Caregivers who brought their child for a primary health care visit in one of six urban Midwestern community health centers between September 2001 and May 2002 were randomly screened for study eligibility (N=1,220). Caregivers were eligible to participate in the study if the child was enrolled in Medicaid or the Indiana State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), if they spoke English, if they had telephone service at home, and if they had a non-Hispanic African-American or white child of age two to 18 years who screened positive for having a special health care need (24). The most frequently cited special health care needs reported by caregivers included asthma, attention and behavioral problems, and chronic allergies. Caregivers who met the eligibility criteria were invited to participate in the study (N=368). A trained research assistant contacted the caregiver to obtain informed consent and arrange for a computer-assisted telephone interview. The Indiana University human subjects review board approved all research procedures, and the community health center directors gave permission to recruit participants from their sites. Each primary caregiver was paid $10 for participation in the study. A total of 257 caregivers completed an interview (257 of 368, or 70 percent). Those excluded either could not be reached by telephone or declined to participate.

Measures

Behavioral and emotional problems were measured with use of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (25). The CBCL includes 20 items that measure social competence and 118 items that rate behavior problems. It provides an age-adjusted index of emotional and behavioral problems as well as internalizing and externalizing problem subscores. The CBCL has been shown to discriminate between children who are referred to mental health services and demographically matched nonreferred children. A CBCL total behavior score greater than 63 indicates clinical need for mental health treatment or counseling. Reliability coefficients for the CBCL have ranged from .84 to .98, and the CBCL has been well established for use with children from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Demographic variables such as race and socioeconomic status accounted for a relatively small proportion of score variance. Thus differences were considered too small to warrant separate norms based on socioeconomic status or race or ethnicity.

The ULSS is a 21-item instrument that is used to measure subjective contextual community-level stressors as potential sources of psychological and emotional stress experienced by persons living in medium to large cities. Each item on the ULSS is answered with reference to a 5-point scale ranging from 1, "no stress at all," to 5, "extremely stressful—more than I can handle." The total score reflects the level of stress associated with day-to-day life in an urban environment. The scale is intended to identify chronic life stress as opposed to acute event stress. The scale's reliability and validity have been established in African-American and Latino groups (23). Previous stress scales did not include sources of stress that are frequently encountered by these groups.

To determine access to health care and satisfaction with the child's health care provider, we used two questions from the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) (26). Access to health care was ascertained by asking, "How much of a problem was it to find a personal doctor or nurse for your child that you were happy with?" Multiple-choice answers included "a big problem, "a small problem," and "not a problem." These responses were dichotomized as either a health care access problem or not a health care access problem. Parents' rating of their satisfaction with their child's health care provider was a continuous variable based on a 10-point scale, with 10 representing the greatest satisfaction with their health care provider and 1 representing the least satisfaction with their provider.

Sociodemographic variables that were recorded for the caregivers included perceptions of their children's health as well as the caregivers' educational attainment, employment status, and marital status. Sociodemographic variables that were recorded for the children included age, race, and gender. The caregivers' perception of their child's health status was measured by using an item from the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ-PF28) (27): "In general, would you say your child's health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?"

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics (t tests and chi square tests) to compare African-American and white respondents' sociodemographic characteristics, access to health care, satisfaction with health care, and urban contextual stressor variables. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the relationship between CBCL scores and the independent variables of interest. To assess the extent to which the sociodemographic variables, access to health care, satisfaction with health care, and contextual community-level stressor variables were related to the variation in CBCL scores, we used a series of multivariate models. Model 1 explains the variation in CBCL scores by using the ULSS scores. In model 2, we expanded the analysis by adding health care access and health care satisfaction variables. In model 3, we expanded the analysis again by adding the sociodemographic and health status variables. Finally, in model 4, we added an interaction term that combined race and urban stress. As each set of variables was entered in the separate models, we determined whether the beta coefficients for the ULSS remained stable or whether access to health care, satisfaction with health care, and the sociodemographic variables modified the relationship with the CBCL score. We used F tests to determine whether the change in R2 was significant with the addition of the variables in models 2, 3, and 4. SAS Version 9.1 was used for all analyses.

Results

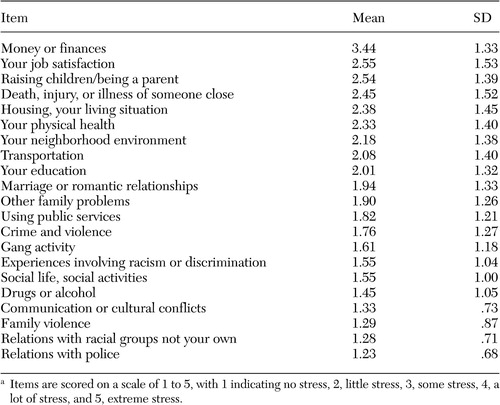

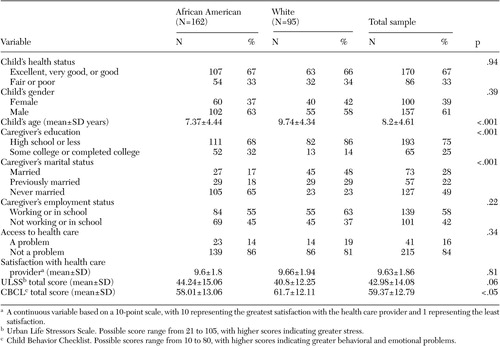

Table 1 lists mean±SD scores for individual items of the ULSS. The item that was the most stressful for parents or caregivers was money and finances (mean score of 3.44). African Americans accounted for 63 percent of the caregivers who completed the study interviews (Table 2). This racial distribution of study participants is comparable to that of the patient population of the health care clinics from which participants were recruited. The children's mean±SD age was 8.2±4.6 years, and 157 (61 percent) were male. Our sample of children with special health care needs had significantly higher CBCL total behavior scores than the published norms based on sex and age (p<.05) (28,24). On the basis of the established cutoff (CBCL total score above 63), 38 percent of our sample (N=98) had behavioral or mental health problems that merited mental health treatment or counseling (28).

Table 2 shows the results of bivariate analyses of study variables by race. White children had significantly higher mean CBCL scores than African-American children. The African-American children were significantly younger. Significant differences were noted between caregivers as well; African-American caregivers were more likely to have attended college, and white caregivers were more likely to be married. The racial difference in the ULSS score approached significance (<.06), with African Americans indicating greater levels of urban life stress.

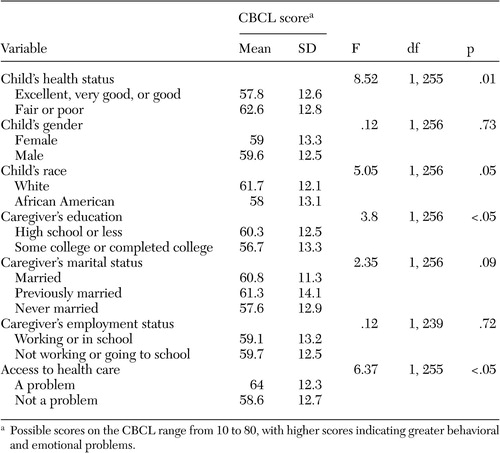

Table 3 shows the results of bivariate analyses of the associations between CBCL scores and other study variables. White race and poorer health status were associated with higher CBCL scores; no significant association was found for age. Children who were rated as being in fair to poor health had higher mean scores on the CBCL than those who were rated as being in excellent to good health. A significant association was also noted between CBCL scores and both health care access and health care satisfaction. Caregivers who rated access to health care as a problem had children with significantly higher CBCL scores, whereas those who reported greater satisfaction with their child's health care provider had children with significantly lower CBCL scores (F=10, df= 1, 253, p<.001).

The relationship between the total ULSS score and CBCL score was highly significant (F=52.47, df=1, 254, p<.001); we observed a positive linear relationship between urban life stress and presence of behavioral and emotional problems among the children in this study.

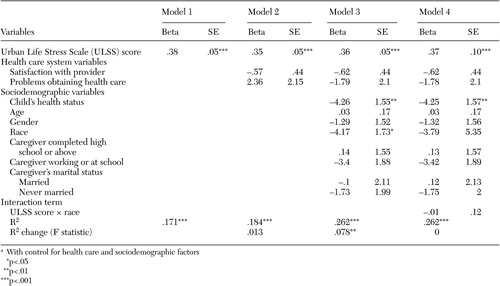

Table 4 shows the results of the four models we used to examine the association between urban community-level contextual stressors and children's behavioral and emotional problems. In model 1, the total ULSS score was regressed on CBCL score, and the association was highly significant (p<.001). In model 2, the health care system-level factors related to the parent's access to and satisfaction with the child's heath provider were added to the model. High ULSS scores continued to be significantly associated with higher CBCL scores, but no such association was noted for the health care system-level factors. This finding was reflected in a nonsignificant change in R2 between model 1 and model 2. In model 3, the sociodemographic and health status variables were introduced, and the ULSS score continued to be significantly associated with CBCL score. The beta coefficients of the ULSS score remained stable across the three models, which indicated that the ULSS was not mediated by health system-level or sociodemographic variables.

Race and child's health status were also significantly associated with CBCL score. White children who were considered to be in fair to poor health and whose parents or caregivers were experiencing higher levels of urban stress were at the highest risk of behavioral and emotional problems. The addition of the sociodemographic variables, particularly race and health status, increased the explanatory efficacy of the model (R2 increased from .18 to .26, p<.01). In model 4, we introduced an interaction term that combined race and ULSS scores. The interaction term for race and urban stress was not significant, indicating that the association between urban stress and total behavioral problems did not differ by race (no change in R2 between models 3 and 4).

Discussion and conclusions

We measured urban community stressors by using the ULSS and found a significant association between urban community-level contextual stressors and the presence of behavioral and emotional problems among children with special health care needs.

In bivariate analyses by race, white children had more behavioral and emotional problems than African-American children. African-American caregivers reported greater amounts of urban stress, particularly stressors related to finances, housing, and employment. The finding of greater urban stress among African-American caregivers is congruent with the results of previous studies that found that African Americans live in urban areas that are more stressful in terms of more poverty and crime (21,29,30). White children were found to have more behavioral and emotional problems even when sociodemographic variables, access to health care, satisfaction with health care, and urban contextual stressors were controlled for, indicating that average total behavioral problems did differ by race. Racial differences in perceptions may contribute to the finding that white children had higher CBCL scores. Because self-report measures are vulnerable to the lens of individual interpretation, white families may be more likely to report comparable behaviors as problematic.

In a fourth model that included an interaction term for race and urban stress, we found that the association between urban stress and children's mental health did not differ by race. These findings are counter to the results of previous studies that suggest that African-American families may be protected against urban stress in ways that provide a buffer against behavioral and emotional problems (16) and that African Americans may be less vulnerable to the negative effects of stressful urban life as a result of earlier and more frequent exposure to urban stress and poverty (30). Further research that explores the complex associations between race, poverty, urban stressors, and mental health are needed.

The best explanatory model in our study (model 3) indicates that urban stressors, race, and child's health status are significantly associated with emotional and behavioral problems among low-income children with special health care needs. Few studies have examined the adverse impact of community context on the mental health of children with special health care needs. In those studies that did examine this impact, lack of insurance and inadequate access to care was put forward by the authors as explaining the relationship between urban stress and behavior and emotional problems (7). In our high-risk sample of children with special health care needs who had public health insurance and had appointments in a primary care clinic, urban stress, race, and health status remained significantly associated with an increased prevalence of behavioral and emotional problems, even when we controlled for problems with access to health care and satisfaction with the health care provider. These findings support those of other studies in which it was concluded that stressful urban environments and limited social support are independently associated with a need for mental health services (13) and that low-income white individuals may be more vulnerable to mental health problems than low-income persons from minority groups (30).

The racial distribution of this study population limits generalization of the findings. White families were in the minority, and other important racial or ethnic groups were not analyzed. Another limitation is a lack of information about persons whom we could not contact or who refused to participate in the study (30 percent of the eligible caregivers). The nonrespondents may represent those who lack a stable residence, a factor that would make them more susceptible to urban stress and potentially greater child mental health problems. The study population was relatively homogeneous in that all children with special health care needs were from low-income families, were insured through Medicaid or SCHIP, and had access to primary care. Thus comparisons with higher-income populations were not possible. The contribution of family dynamics (14) to children's mental health was not explored.

Given that there are severe limitations on mental health care resources for children in general, children with special health care needs who are poor and have behavioral and emotional problems are extremely vulnerable. Although a large proportion of mental health services for children are delivered within the school system (31), current statewide budget cuts are threatening the continuation of these services. Primary care physicians have increasingly become the de facto providers of mental health services for low-income families, particularly families that include children who have special health care needs. Given the increasing time constraints faced by primary care physicians, improved systems of care are needed in which ancillary staff, such as nurses and social workers, can assist in addressing mental health care needs.

The need for an ongoing source of coordinated health care—now designated officially as the "medical home"—for all children is a priority for child health policy reform (32,33). A medical home is vital for children with special health care needs, because these children have chronic medical problems and often receive medical services from multiple sources. Primary care physicians have been given chief responsibility for establishing medical homes. The results of this study suggest that the assessment of psychosocial issues may reveal opportunities to intervene in the case of factors that exacerbate mental health problems among children. Thus primary care physicians will need to position themselves in partnerships with community-based organizations to assist families who are experiencing life stressors that ultimately lead to poor mental health among children. Moreover, efforts are needed at the public policy level to address social inequities such as inadequate employment, housing, and education that have been repeatedly identified as adversely affecting health.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant U01-HS10453-S from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and grant P30-NR-05035 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) to the Center for Enhancing Quality of Life in Chronic Illness at Indiana University School of Nursing.

Dr. Jaffee is affiliated with the College of Human Services and Health Professions, School of Social Work, of Syracuse University, Sims Hall, Syracuse, New York 13244 (e-mail, kd [email protected]). Dr. Liu and Dr. Swigonski are with Children's Health Services Research at Indiana School of Medicine in Indianapolis. Dr. Canty-Mitchell is with the College of Nursing at the Health Sciences Center of the University of South Florida. Ms. Qi is with the biostatistics division of the Indiana University School of Medicine. Dr. Austin is with the Indiana University School of Nursing.

|

Table 1. Mean scores on the Urban Life Stress Scale for a sample of 257 caregivers of low-income children with special health care needsa

a Items are scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating no stress, 2, little stress, 3, some stress, 4, a lot of stress, and 5, extreme stress.

|

Table 2. Characteristics of caregivers of 257 low-income children with special health care needs, by race

|

Table 3. Associations between Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) score and sociodemographic, health care, and urban life stress variables in a sample of 257 caregivers of low-income children with special health care needs

|

Table 4. Ordinary-least-squares regression models of behavioral and emotional problems on urban life stress in a sample of 257 caregivers of low-income children with special health care needsa

a With control for health care and sociodemographic factors

1. Breslau N: Psychiatric disorder in children with physical disabilities. American Academy of Child Psychiatry 24:87–94, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. DosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, et al: Mental health services for youths in foster care and disabled youths. American Journal of Public Health 91:1094–1099, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Harman JS, Childs GE, Kelleher KJ: Mental health care utilization and expenditures by children in foster care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 154:1114–1117, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Gortmaker SL, Walker DK, Weitzman M, et al: Chronic conditions, socioeconomic risks, and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 85:267–276, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wolman C, Resnick M, Harris L, et al: Emotional well-being among adolescents with and without chronic conditions. Journal of Adolescent Health 15:199–204, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Anderson RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1994Google Scholar

7. McPherson M, Arango P, Fow H, et al: A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics 102:137–140, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA: The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 37:293–310, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. McLeod JD, Edwards K: Contextual determinants of children's responses to poverty. Social Forces 73:1487–1516, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

10. McLeod JD, Nonnemaker JM: Poverty and child emotional and behavioral problems: racial/ethnic differences in processes and effects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:137–161, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Shumow L, Vandell DL, Posner J: Perceptions of danger: a psychological mediator of neighborhood demographic characteristics. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:468–478, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bell C, Jenkins E: Community violence and children on Chicago's Southside. Psychiatry 56:46–54, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Dubow EF, Edwards S, Ippolito MF: Life stressors, neighborhood disadvantage, and resources: a focus on inner-city children's adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 26:130–144, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, et al: A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development 63:526–541, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, et al: Family economic stress and adjustment of early adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology 29:206–219, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Samaan RA: The influences of race, ethnicity, and poverty on the mental health of children. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 11:100–110, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Klebanov K, et al: Do neighborhoods influence child adolescent development. American Journal of Sociology 99:353–394, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Jargowsky P: Ghetto poverty among blacks in the 1980s. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 13:288–310, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Jargowsky P: Poverty and place: ghettos, barrios, and the American city. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1997Google Scholar

20. Roberts EM: Neighborhood social environment and the distribution of low birthweight in Chicago. American Journal of Public Health 87:597–603, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Jaffee KD, Perloff JD: An ecological analysis of racial differences in low birthweight. Health and Social Work 28:9–22, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sampson R, Morenoff J, Earls F: Beyond social capital: spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review 64:633–660, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Sanders-Phillips K, Harrell S: Correlates of health promotion behaviors in low-income black women and Latinas. American Journal of Health Promotion 10:308–317, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bethell C, Read D, Stein RE, et al: Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambulatory Pediatrics 2:38–48, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, Vt, University of Vermont, department of psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

26. McGee J, Kanouse DE, Sofaer S, et al: Making survey results easy to report to consumers: how reporting needs guided survey design in CAHPS. Medical Care 37(3 suppl):MS32-MS40, 1999Google Scholar

27. Landraf JM, Ware JE: The Child Health Questionnaire User's Manual. Boston, The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1999Google Scholar

28. Canty-Mitchell J, Austin J, Jaffee K, et al: Behavioral and mental health problems in low-income children with special health care needs (CSHCN). Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 18:79–87, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Massey D, Denton N: American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1993Google Scholar

30. Schulz A, Williams D, Israel B, et al: Unfair treatment, neighborhood effects, and mental health in the Detroit metropolitan area. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:314–332, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Hoagwood K, Burns B, Kiser L, et al: Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatric Services 52:1179–1189, 2001Link, Google Scholar

32. American Academy of Pediatrics: Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee: the medical home. Pediatrics 110:184–186, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Measuring Success for Healthy People 2010: National Agenda for Children With Special Health Care Needs. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1999. Available at www.mchb.hrsa.gov/programs/specialneeds/measuresuccess.htmGoogle Scholar