The Development and Implementation of Case Management for Substance Use Disorders in North America and Europe

Abstract

Because of the multifaceted, chronic, and relapsing nature of substance use disorders, case management has been adapted to work with persons who have these disorders. Deliberate implementation has been identified as a powerful determinant of successful case management. This article focuses on six key questions about implementation of case management services on the basis of a comparison of experiences from the United States, the Netherlands, and Belgium. It was found that case management has been applied in various populations with substance use disorders, and distinct models have been associated with positive effects, such as increased treatment participation and retention, greater use of services, and beneficial drug-related outcomes. Program fidelity, robust implementation, extensive training and supervision, administrative support, a team approach, integration in a comprehensive network of services, and minimal continuity have all been linked to successful implementation.

Case management is regarded as one of the most important innovations in mental health and community care of the past decades (1). It is a client-centered strategy to improve coordination and continuity of care, especially for persons who have multiple needs (2). Regardless of the controversy of whether, in what form, and to what extent case management is effective, this intervention has a long history for the treatment of various populations of persons with mental illness in the United States, Australia, and Canada and in several European countries (3,4,5,6,7).

Since the 1980s, case management has been adapted to work with persons with substance use disorders (8,9,10), which were increasingly becoming recognized as multifaceted, chronic, and relapsing disorders that required a comprehensive and continuous approach (11,12). Although modeled after mental health examples, case management for persons with substance use disorders was developed separately, illustrating the originally strong distinction between the substance abuse and mental health treatment sectors in several countries (13,14,15). Lightfoot and colleagues (16) were the first to show that case management could reduce attrition from treatment and improve both psychosocial and drug and alcohol outcomes among persons with substance use disorders.

Since the 1990s, hundreds of programs in Canada and the United States and some in Europe—for example, Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium—have implemented case management (14,17), expecting a positive impact on treatment participation and retention, coordination of service delivery, and drug-related outcomes. The increased need for case management has been attributed to the growing complexity of individuals' problems and systems of care (11,18).

Despite its widespread application and popularity, case management is not unanimously defined, and its practice varies from place to place because of diverging objectives, distinct target populations, program and system variables, and other immediate local concerns (19,20,21). One of the first definitions described case management as "that part of substance abuse treatment that provides ongoing supportive care to clients and facilitates linking with appropriate helping resources in the community" (22). A more accurate way of characterizing case management is to postulate its basic functions: assessment, planning, linking, monitoring, and advocacy (14). Furthermore, some broad principles are true of almost every application of case management: community based, client driven, pragmatic, flexible, anticipatory, culturally sensitive, and offering a single point of contact.

Given that deliberate conceptualization and implementation have been identified as powerful determinants of successful practice and outcomes (6,21,23,24,25), we conducted a comparative review of available literature focusing on issues concerning the implementation of case management for substance use disorders. The goal of the review was to provide insight into some of the do's and don't's when developing this intervention on the basis of experiences in North America (the United States) and Europe (the Netherlands and Belgium)—countries that loosely represent three points on a continuum.

This comparison started from exploring similarities and dissimilarities between these selected countries during a workshop on case management at the Third International Symposium on Substance Abuse Treatment and Special Target Groups, held March 5 and 6, 2001, in Blankenberge, Belgium (26). Discussions between researchers from these countries led to the joint identification of six key questions, which are elaborated on in this article on the basis of available literature and empirical evidence.

Information was obtained through repeated searches in MEDLINE, PsycLIT, PubMed, and the Web of Science for articles published since the 1990s, using the terms "substance abuse-addiction-substance use disorders," "case management," and "development-implementation."

Key questions

Which problems are addressed with case management, and what are its objectives and target group? The observation that many persons with substance use disorders have significant problems in addition to abusing substances has been the main impetus for using case management as an enhancement and supplement to substance abuse treatment (27,28,29,30,31). In the United States, the paucity and selective accessibility of available services, shortcomings in the overall quality of service delivery (accountability, continuity, comprehensiveness, coordination, effectiveness, and efficiency), and cost containment were further incentives for implementing case management (14,18,19,32). The implementation of case management in the Netherlands was not driven merely by economic concerns but rather by the poor quality of life of many chronic addicts and the nuisance they cause in city centers (31). In Belgium, the chronic and complex problems of many substance abusers and the lack of coordination and continuity of care were the main reasons for introducing case management (30).

Unlike in the United States, case management has not been applied as widely among substance abusers in Europe because of better availability and accessibility of services, less stress on cost containment, and conflicting outcomes about the effectiveness of case management for persons with mental illness, among other reasons. However, recent reforms in substance abuse treatment—for example, in the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium—have shifted the focus toward accessibility, continuity, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency and stimulated interest in case management (15,33,34). Since 1995, more than 50 projects have been developed in the Netherlands that make use of case management, whereas the number of case management projects for this population in Belgium is limited to five to ten (30,31).

In the United States, case management has been implemented successfully for enhancing treatment participation and retention among substance abusers in general (35,36,37,38) and for populations with multiple needs that experience specific barriers in obtaining or keeping in touch with services, such as pregnant women, mothers, adolescents, persons who are chronically publicly inebriated, persons with dual diagnoses, and persons with HIV infection (11,39,40,41,42,43,44). Most of these programs intend to promote abstinence, whereas case management programs in Europe apply a harm-reduction perspective. In the Netherlands, the implementation of case management has been directed mainly at severely addicted persons, such as street prostitutes, mothers of young children, homeless persons, and persons with dual diagnoses, who are often served inadequately or not at all by existing services. According to program providers, case management has contributed substantially to the stabilization of these persons' situation (45). In Belgium, case management has mainly been reserved for substance abusers with multiple and chronic problems, resulting in improved drug-related outcomes and better coordination of the delivery of services (46).

Target populations may also include persons with substance use disorders who are involved in the criminal justice system, and these interventions have been associated with reduced drug use and recidivism and with increased service use (47,48,49). However, uncertainty remains about the differential effect of coercion in case management (50,51). This intervention has further been used to address "the most problematic clients," an approach that has been associated with adverse outcomes in the field of mental health care (6), but various studies among substance abusers have shown cost-effectiveness and beneficial outcomes (16,40,52,53,54,55,56). Nevertheless, several authors have reported practical problems—for example, the difficulty of long-term planning, increased risk of burnout among case managers, and clients' becoming totally dependent on their case manager (21,46,53,57).

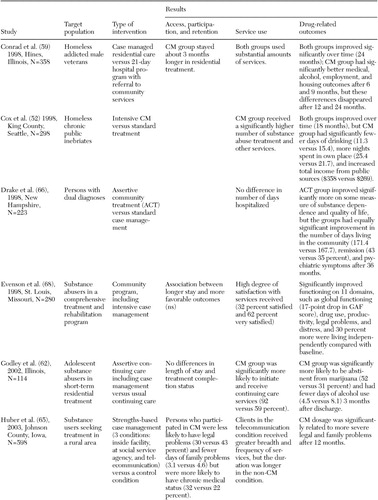

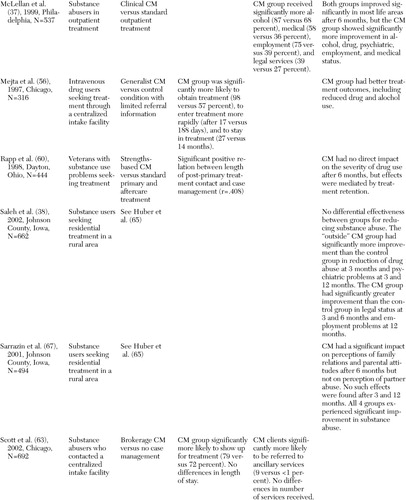

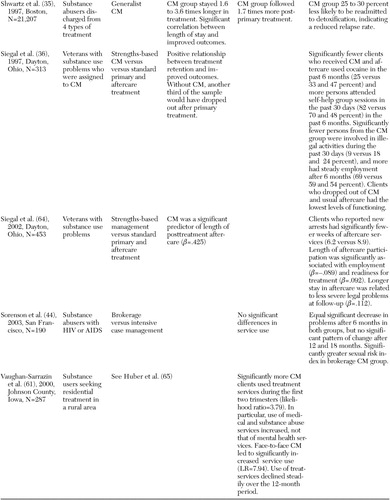

An overview of recently published (1997 to 2003) peer-reviewed studies of case management that have included at least 100 substance abusers revealed that case management has been relatively successful for achieving several of the postulated goals in the United States, whereas similar outcome studies are still forthcoming in Europe (Table 1). Several controlled studies have shown significant improvements in treatment access, participation, and retention or service use among clients who have received case management services (36,37,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65), whereas evidence on the effects on drug-related outcomes is still conflicting. Generally, small to moderate improvements have been demonstrated among clients who received case management services (58,62,64,66,67), but these effects sometimes tended to decline over time (after nine to 12 months) (38,59) or did not differ significantly from those of similar control interventions, such as behavioral skills training and other models of case management (25,44,60). Finally, various uncontrolled studies have shown significantly improved outcomes compared with baseline assessments (34,35,46,68). However, in the absence of a control condition, such effects may have wrongly been attributed to case management.

What is the position of case management in the system of services, and how can cooperation and coordination between services be enhanced? Several authors have argued that the success of case management depends largely on its integration within a comprehensive network of services (8,21,69,70,71). Case management risks being just one more fragmented piece of the system of services if it is not exquisitely sensitive to potential system-related barriers, such as waiting lists, inconsistent diagnoses, opposing views, and lack of housing and transportation (72).

McLellan and colleagues (37) found no effects of case management 12 months after implementation but did find effects after 26 months. They concluded that there was a strong influence of various system variables—for example, program fidelity and availability and accessibility of services—and recommended extensive training and supervision to foster collaboration and precontracting of services to ascertain their availability. Access to treatment can be markedly improved when case managers have funds with which to pay for treatment (58). In addition, formal agreements and protocols are needed concerning the tasks, responsibilities, and authorities of case managers and other service providers involved; the use of common assessment and planning tools; and exchange and management of client information (13,14,21,57,73).

Case management can be implemented as a modality provided by or attached to a specific organization, such as a hospital or a detoxification center, or as a specific service jointly organized by several providers to link clients to these and other services. The former program structure has been widely applied in the United States for enhancing participation and retention and reducing relapse, whereas the latter is frequently used in Belgium and the Netherlands to address populations at risk of falling through the cracks of the system.

Vaughan-Sarrazin and colleagues (61) studied the differential impact of programs' locations and compared the effectiveness of three types of case management with a control condition. The variant that involved case managers housed inside the facility was associated with significantly greater service use compared with the other conditions, which suggests that the accessibility and availability of case management programs mediate the success of these programs.

What model of case management should be used, and which are crucial aspects of effective case management? Although most practical examples only vaguely resemble the pure version of a case management model, four models of case management are usually distinguished for working with substance use disorders: the brokerage-generalist model, assertive community treatment-intensive case management, the strengths-based model, and clinical case management (14,19). Model selection should be dictated by what services are already available, the objectives and target population, and any available empirical evidence.

Assertive community treatment, and especially intensive case management, with its focus on a comprehensive (team) approach and the provision of assertive outreach and direct counseling services, has been used in the United States for reintegrating incarcerated offenders, among other populations (24,47,49). A randomized study of 135 parolees, half of whom received case management services, showed little differential effect on drug use, but some improvement was found in relation to risk behavior and recidivism (24).

Random assignment to intensive case management compared with two other interventions was associated with a decline in drug use and criminal involvement and an increase in treatment participation among almost 1,400 arrestees (49). In addition, intensive case management has been applied successfully in other populations with complex and severe problems—for example, homeless persons and persons with dual diagnoses (40,42,52,53,66,68). Intensive case management is the predominant model in Belgium and the Netherlands and has been associated with the delivery of more comprehensive and individualized services and improved outcomes (31,46).

Two large studies in Dayton, Ohio, and in Iowa, sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, have applied strengths-based case management among persons with substance abuse who are entering initial treatment (Table 1). The Ohio study found evidence for improved employment functioning and enhanced treatment retention, which, in turn, was associated with a positive effect on outcomes concerning drug use and criminal involvement (36,60,64,74,75). According to clients, retention was promoted by the client-driven nature of goal setting and was facilitated by case managers' assistance in teaching clients how to set goals (76). The Iowa study showed an impact of case management on the use of medical and substance abuse services and moderate, but fading, effects on legal, employment, family, and psychiatric problems (32,38,61,65,67).

Brokerage models and other brief approaches to case management have usually not demonstrated any discernable benefits of case management compared with control groups who did not receive case management services (77,78). However, recent studies have shown a positive impact of case management on service use and access to treatment (66) and equal effectiveness compared with intensive case management (44). Generalist or standard case management has been associated with significant positive effects on treatment participation and retention and relapse (35,58). Clinical case management, which combines resource acquisition and clinical activities, has rarely been applied among persons with substance use disorders but was successful in at least one study (37). Other authors have stated that combining the role of counselor and case manager is problematic, because it dilutes both aspects of the program (24).

In summary, as opposed to case management for persons with mental illness (3,6,79,80), little information is available about crucial features of distinct models and their effectiveness for specific substance abusing populations.

Which qualifications and skills should case managers have, and what types of support should be provided? Several authors assume that previous work experience, extensive training, knowledge about the health care and social welfare systems, and communication and interpersonal skills are at least as important as formal qualifications (14,31,34). Only some programs have involved people who have recovered from addictions as case managers (81), but no information is available about the differential impact of case management by professionals or peers. The client-case manager relationship has been identified as crucial for promoting case management participation and related outcomes, and the application of a strengths-based approach can stimulate clients' involvement (34,46,74,76).

Analyses of case management activities and program fidelity have shown large variations among case managers, not only within but also across programs (13,14,25,35,44,68). Poor program fidelity and nonrobust implementation of case management have been associated with worse outcomes, but fidelity and implementation can be optimized by extensive initial training, regular supervision, administrative support, application of protocols and manuals, treatment planning, and a team approach (13,25,37).

Variety across programs has resulted in attempts to standardize and guide case management in the United States. The National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors identified case management as one of eight counseling skills (82), and the commonly cited case management functions have been incorporated into the referral and service coordination practice dimensions of the addiction counseling competencies (83). In the Netherlands, a Delphi study was organized to reach a broad consensus on the core features of case management, resulting in a manual that will serve as a touchstone for the future development, implementation, and evaluation of case management (31,84). The Delphi method comprises a series of questionnaires sent to a preselected group of experts—for example, clients, case managers, and program directors—who respond to the problems posed individually and who are able to refine their views as the group's work progresses (85). It is believed that the group will converge toward the best response through this consensus process, based on structuring of the information flow and feedback to the participants.

Case managers' caseloads vary but usually do not exceed 15 to 20 clients for a case manager who is providing intensive contacts to substance abusers who have multiple and complex problems (13,21,34,41,52). A team approach helps to deal with large and difficult caseloads but also to extend availability and guarantee case managers' safety (34,86). Most researchers have found little effect of the intensity of mental health case management (6,35,44), whereas others have related high "dosages" of case management with either improved or adverse outcomes (34,68).

How should case management projects best be financed, and how can their continuity be guaranteed? The burgeoning interest in managed care financing structures resulted in an explosive growth of case management initiatives in the United States during the 1990s (32). Most programs have been set up as experiments, but, despite positive results, only some have been integrated into the service system on a long-term basis. On the other hand, case management programs in the Netherlands became part of the system of services shortly after implementation and without many indications of effectiveness (31). Both observations illustrate that continued funding might be predicted on the basis of issues that have little to do with success or failure of the intervention itself.

Developing projects should be given sufficient time—three to five years—to realize their objectives, given that it has been shown that it may take up to two years before case management generates the intended outcomes (37). Alternative or flexible forms of reimbursement need to be negotiated with insurance companies, because case managers' activities often represent departures from traditional interventions in substance abuse treatment (87). In addition, a budget for occasional client expenses—for example, child care, clothing, and public transportation—can facilitate case management (37,43,57). Ultimately, continued funding should be based on a thorough evaluation of the program's postulated goals.

Which standards should be used to evaluate case management? Effectiveness needs to be evaluated according to scientific standards, but requirements from commissioning and subsidizing authorities should also be taken into account (14). Evaluation should start from an accurate representation of what the intervention entails (23). Without this knowledge, it is only possible to vaguely search for outcomes that might be more or less attributable to case management. Besides outcome indicators, process data should be collected that describe the degree to which the planned intervention is actually delivered, the impact of other factors on the intervention, and the specific outcomes that can be attributed to case management (14,47).

Researchers have identified several potential confounding factors—for example, individual case managers' personalities, client characteristics, motivation, legal status, and treatment participation and retention—that affect the direct impact of case management on clients' functioning (25,36,52,68,60,64,88,89). Contextual differences cause further methodologic problems in the evaluation of case management. To extend current knowledge about the effectiveness of case management for persons with substance use disorders, more randomized controlled studies with large samples are needed, especially in Europe. Also, a longitudinal scope and qualitative research that focuses on specific aspects of case management and the role of mediating variables could provide further insights into the factors that make case management work.

Conclusions

In both the United States and Europe, case management is regarded as an important supplement to traditional substance abuse services, as it provides an innovative approach—client centered, comprehensive, and community based—and contributes to improved access, participation, retention, service use, and client outcomes. Compared with case management for persons with mental illness, case management for persons with substance use disorders has fairly little evidence available of effectiveness.

Contextual differences, specific target populations, diverging objectives, less tradition of community care, few randomized and controlled trials, and unrealistic expectations about the effectiveness of case management in this population may account for this lack of evidence. Especially in Europe, more randomized controlled trials that include sufficiently large samples are needed, as well as qualitative studies, in order to better understand distinct aspects of case management and their impact on client outcomes and system variables.

Case management for substance use disorders is no panacea, but it positively affects the delivery of services and can help to stabilize or improve an individual's complex situation. On the basis of empirical findings from the United States, the Netherlands, and Belgium, several prerequisites for a well-conceptualized implementation of this intervention can be mentioned. Integration of the program in a comprehensive network of services, accessibility and availability, provision of direct services, use of a team approach, application of a strengths-based perspective, intensive training, and regular supervision all contribute to successful implementation and, consequently, to beneficial outcomes.

Still, the variety of case management practices within and across programs remains a major concern. Development of program protocols and manuals and the identification of key features of distinct models can contribute to a more consistent application of this intervention.

Finally, although case management for persons with substance use disorders has evolved somewhat independently, many similarities can be observed with mental health case management. Therefore, further evolutions in this sector should be closely followed, especially for identifying the crucial features of case management. Moreover, a comparison of case management for both populations may reveal unique aspects of each intervention that allow optimization of case management practices among patients with mental illness, persons with substance use disorders, and persons with dual diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

The Third International Symposium on Substance Abuse Treatment and Special Target Groups, held March 3 to 5, 2001, in Blankenberge, Belgium, was financially supported by the Province of East Flanders and the European Federation of Therapeutic Communities.

Dr. Vanderplasschen is affiliated with the department of orthopedagogics at Ghent University, H. Dunantlaan 2, B-9000, Ghent, Belgium (e-mail, [email protected]). Professor Rapp is with the center for interventions, treatment, and addictions research at Wright State University School of Medicine in Dayton, Ohio. Dr. Wolf is with Trimbos Institute in Utrecht, the Netherlands, and with the department of social medicine at Catholic University of Nijmegen in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Dr. Broekaert is with the department of orthopedagogics at Ghent University.

|

Table 1. Overview of main results of recently published studies (1997 to 2003) in peer-reviewed journals about case management (CM) for persons with substance use disorders (N>100)

|

|

1. Holloway F, Carson J: Case management: an update. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 47(3):21–31, 2001Google Scholar

2. Moxley D: The Practice of Case Management: Sage Human Services Guides, vol 58. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1989Google Scholar

3. Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services 51:1410–1421, 2000Link, Google Scholar

4. Rosen A, Teesson M: Does case management work? The evidence and the abuse of evidence-based medicine. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 35:731–746, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rochefort DA, Goering P: "More a link than a division": how Canada has learned from US mental health policy. Health Affairs 17(5):110–127, 1998Google Scholar

6. Burns T, Fioritti A, Holloway F, et al: Case management and assertive community treatment in Europe. Psychiatric Services 52:631–636, 2001Link, Google Scholar

7. Erdmann Y, Wilson R: Managed care: a view from Europe. Annual Review of Public Health 22:273–291, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Graham K, Birchmore Timney C: Case management in addictions treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 7:181–188, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ogborne AC, Rush BR: The coordination of treatment services for problem drinkers: problems and prospects. British Journal of Addiction 78:131–138, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rush B, Ekdahl A: Recent trends in the development of alcohol and drug treatment services in Ontario. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 51:514–522, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Brindis CD, Theidon KS: The role of case management in substance abuse treatment services for women and their children. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 29:79–88, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. McLellan AT: Have we evaluated addiction treatment correctly? Implications from a chronic care perspective. Addiction 97:249–252, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Ridgely MS, Jerell JM: Analysis of three interventions for substance abuse treatment of severely mentally ill people. Community Mental Health Journal 32:561–572, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Comprehensive Case Management for Substance Abuse Treatment, TIP Series 27. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998Google Scholar

15. Broekaert E, Vanderplasschen W: Towards the integration of treatment systems for substance abusers: report on the second international symposium on substance abuse treatment and special target groups. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 35:237–245, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Lightfoot L, Rosenbaum P, Ogurzsoff S, et al: Final Report of the Kingston Treatment Programmed Development Research Project. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, Department of Health and Welfare, Health Promotion Directorate, 1982Google Scholar

17. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA): Annual Report on the State of the Drug Problem in the European Union. Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2001Google Scholar

18. Willenbring M: Case management applications in substance use disorders, in Case Management and Substance Abuse Treatment: Practice and Experience. Edited by Siegal H, Rapp R. New York, Springer, 1996Google Scholar

19. Ridgely MS, Willenbring M: Application of case management to drug abuse treatment: overview of models and research issues, in Progress and Issues in Case Management, NIDA Research Monograph 127. Edited by Ashery RS. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1992Google Scholar

20. Ridgely MS: Practical issues in the application of case management to substance abuse treatment, in Case Management and Substance Abuse Treatment: Practice and Experience. Edited by Siegal H, Rapp R. New York, Springer, 1996Google Scholar

21. Wolf J, Mensink C, van der Lubbe P: Case management voor langdurig verslaafden met meervoudige problemen: een systematisch overzicht van interventie en effect. [Case Management for Chronic Addicts With Multiple Problems: A Systematic Overview of Intervention and Effect.] Utrecht, Trimbos-instituut, Ontwikkelcentrum Sociaal Verslavingsbeleid, 2002Google Scholar

22. Birchmore Timney C, Graham K: A survey of case management practices in addictions programs. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 6:103–127Google Scholar

23. Perl HI, Jacobs ML: Case management models for homeless persons with alcohol and other drug problems: an overview of the NIAAA research demonstration program, in Progress and Issues in Case Management, NIDA Research Monograph 127. Edited by Ashery RS. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1992Google Scholar

24. Inciardi JA, Martin SS, Butzin CA, et al: An effective model of prison-based treatment for drug-involved offenders. Journal of Drug Issues 27:261–278, 1996Google Scholar

25. Jerrell JM, Ridgely MS: Impact of robustness of program implementation on outcomes of clients in dual diagnosis programs. Psychiatric Services 50:109–112, 1999Link, Google Scholar

26. Broekaert E, Vandevelde S, Vanderplasschen W, et al: Two decades of "research-practice" encounters in the development of European therapeutic communities for substance abusers. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 56:371–377, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Oppenheimer E, Sheehan M, Taylor C: Letting the client speak: drug misusers and the process of help seeking. British Journal of Addiction 83:635–647, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Westermeyer J: Non-treatment factors affecting treatment outcome in substance abuse. American Journal of Substance Abuse 15:13–29, 1989Google Scholar

29. Sullivan W, Hartmann D, Dillon D, et al: Implementing case management in alcohol and drug treatment. Families in Society. Journal of Contemporary Social Services 75:67–73, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Vanderplasschen W, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Oost P: Co-ordination and continuity of care in substance abuse treatment: an evaluation study in Belgium. European Addiction Research 8:10–21, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Wolf J, Planije M: Case management voor langdurig verslaafden met meervoudige problemen. [Case Management for Chronic Addicts With Multiple Problems.] Utrecht, Trimbos-instituut, Ontwikkelcentrum Sociaal Verslavingsbeleid, 2002Google Scholar

32. Hall JA, Carswell C, Walsh E, et al: Iowa case management: innovative social casework. Social Work 47:132–141, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. De Weert-van Oene G, Schrijvers A: Van lappendeken naar zorgcircuit: circuitvorming in de Utrechtse verslavingszorg. [From Patchwork to Network: Towards the Integration of Treatment Services in Substance Abuse Treatment in Utrecht, the Netherlands.] Utrecht,Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht, Vakgroep Algemene gezondheidszorg en epidemiologie, 1992Google Scholar

34. Oliva H, Görgen W, Schlanstedt G, et al: Case management in der Suchtkranken- und Drogenhilfe: Ergebnisse des Kooperationsmodells nachgehende Sozialarbeit: Modellbestandteil Case management, Berichtszeitraum 1995–2000. [Case Management in Alcohol and Drug Treatment: Results of the Cooperation Pilot Project of Follow-up Social Work.] Köln, Fogs, Gesellschaft für Forschung und Beratung in Gesundheits- und Sozialbereich mbH, 2001Google Scholar

35. Shwartz M, Baker G, Mulvey KP, et al: Improving publicly funded substance abuse treatment: the value of case management. American Journal of Public Health 87:1659–1664, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Siegal H, Rapp RC, Li L, et al: The role of case management in retaining clients in substance abuse treatment: an exploratory analysis. Journal of Drug Issues 27:821–831, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

37. McLellan AT, Hagan TA, Levine M, et al: Does clinical case management improve outpatient addiction treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 55:91–103, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Saleh SS, Vaughn T, Hall JA, et al: Effectiveness of case management in substance abuse treatment. Care Management Journal 3:172–177, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Willenbring ML, Whelan JA, Dahlquist JS, et al: Community treatment of the chronic public inebriate: I. implementation. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 7(2):79–97, 1990Google Scholar

40. Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SK, et al: Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment versus standard case management for persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Health Services Research 33:40–53, 1998Google Scholar

41. Godley SH, Godley MD, Pratt A, et al.: Case management services for adolescent substance abusers: a program description. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 11:309–317, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Braucht GN, Reichardt CS, Geissler LJ, et al: Effective services for homeless substance abusers. Journal of Addictive Diseases 14:87–109, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Laken MP, Ager JW: Effects of case management on retention in prenatal substance abuse treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Dependence 22:439–448, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Sorensen JL, Dilley J, London J, et al: Case management for substance abusers with HIV/AIDS: a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 29:133–150, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Broër C, Noyon R: Over last en beleid: Regioplan Stad en Land. [About Nuisance and Policy: Master Plan for the City and Region.] Amsterdam, Regioplan Stad en Land, 1999Google Scholar

46. Vanderplasschen W, Lievens K, Broekaert E: Implementatie van een methodiek van case management in de drughulpverlening: een proefproject in de provincie Oost-Vlaanderen, Orthopedagogische Reeks Gent Nummer 14. [Implementation of a Model of Case Management in Substance Abuse Treatment: A Pilot Project in the Province of East-Flanders, Orthopedagogical Issues Ghent, volume 14.] Gent, Universiteit Gent, Vakgroep Orthopedagogiek, 2001Google Scholar

47. Martin SS, Scarpitti FR: An intensive case management approach for paroled IV drug users. Journal of Drug Issues 23:43–59, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

48. Van Stelle KR, Mauser E, Moberg DP: Recidivism to the criminal justice system of substance abusing offenders diverted into treatment. Crime and Delinquency 40:175–196, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

49. De Koning PJ, Hessing DJ: De kosten van het drugbeleid. [The costs of drug policy.] Recht der Werkelijkheid 1:1–24, 2000Google Scholar

50. Rhodes W, Gross M: Case Management Reduces Drug Use and Criminality Among Drug-Involved Arrestees: An Experimental Study of an HIV Prevention Intervention: NIJ Research Report. Washington, DC, Office of Justice Programs, 1996Google Scholar

51. Cook F: Case management models linking criminal justice and treatment, in Progress and Issues in Case Management, NIDA Research Monograph 127. Edited by Ashery RS. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1992Google Scholar

52. Cox GB, Walker RD, Freng SA, et al: Outcome of a controlled trial of the effectiveness of intensive case management for chronic public inebriates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 59:523–532, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Bearman D, Claydon K, Kincheloe J, et al: Breaking the cycle of dependency: dual diagnosis and AFDC families. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 29:359–367, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, et al: The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 18:603–608, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Jerrell JM, Hu T, Ridgely MS: Cost-effectiveness of substance disorder interventions for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:283–297, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Jerrell JM: Toward cost-effective care for persons with dual diagnoses. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:329–337, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Yates R, Gilman M: Seeing More Drug Users: Outreach Work and Beyond. Manchester, England, Lifeline Project, 1990Google Scholar

58. Mejta CL, Bokos PR, Mickenberg J, et al: Improving substance abuse treatment access and retention using a case management approach. Journal of Drug Issues 27:329–340, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

59. Conrad KJ, Hultman CI, Pope AR, et al: Case managed residential care for homeless addicted veterans: results of a true experiment. Medical Care 36:40–53, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Rapp RC, Siegal HA, Li L, et al: Predicting post-primary treatment services and drug use outcome: a multivariate analysis. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 24:603–615, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Hall JA, Rick GS: Impact of Iowa case management on use of health services by rural clients in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Drug Issues 30:435–463, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

62. Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, et al: Preliminary outcomes from the assertive continuing care experiment for adolescents discharged from residential treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 23:21–32, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Scott CK, Sherman RE, Foss MA, et al: Impact of centralized intake on case management services. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 34:51–57, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Siegal HA, Li L, Rapp RC: Case management as a therapeutic enhancement: impact on post-treatment criminality. Journal of Addictive Diseases 21:37–46, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Huber DL, Sarrazin MV, Vaughn T, et al: Evaluating the impact of case management dosage. Nursing Research 52:276–288, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Drake RE, McHugo G, Clark R, et al: Assertive community treatment for patients with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorder: a clinical trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:201–215, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Sarrazin MV, Huber DL, Hall JA: Impact of Iowa case management on family functioning for substance abuse treatment clients. Adolescent and Family Health 2:132–140, 2001Google Scholar

68. Evenson RC, Binner PR, Cho DW, et al: An outcome study of Missouri's CSTAR alcohol and drug abuse programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 15:143–150, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Graham K, Timney C, Bois C, et al: Continuity of care in addictions treatment: the role of advocacy and coordination in case management. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 21:433–451, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

70. Ashery RS: Case management for substance abusers: more issues than answers, in Case Management and Substance Abuse Treatment: Practice and Experience. Edited by Siegal H, Rapp R. New York, Springer, 1996Google Scholar

71. Kirby MW, Braucht GN: Intensive case management for homeless people with alcohol and other drug problems: Denver. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 10:187–200, 1993Google Scholar

72. Godley SH, Finch M, Dougan L, et al: Case management for dually diagnosed individuals involved in the criminal justice system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 18:137–148, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

73. Mejta C, Bokos P, Maslar EM, et al: The effectiveness of case management in working with intravenous drug users, in The Effectiveness of Innovative Approaches in the Treatment of Drug Abuse. Edited by Tims FM, Inciardi JA, Fletcher BW, et al. Westport, Conn, Greenwood, 1997Google Scholar

74. Siegal HA, Rapp RC, Kelliher CW, et al: The strengths perspective of case management: a promising inpatient substance abuse treatment enhancement. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 27:67–72, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Siegal HA, Fisher JA, Rapp RC, et al: Enhancing substance abuse treatment with case management: its impact on employment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 13:93–98, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

76. Brun C, Rapp RC: Strengths-based case management: individuals' perspectives on strengths and the case manager relations. Social Work 46:278–288, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Lidz V, Bux DA, Platt JJ, et al: Transitional case management: a service model for AIDS outreach projects, in Progress and Issues in Case Management, NIDA Research Monograph 127. Edited by Ashery RS. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1992Google Scholar

78. Falck R, Siegal HA, Carlson RG: Case management to enhance AIDS risk reduction for injection drug users and crack users: theoretical and practical considerations, in Progress and Issues in Case Management, NIDA Research Monograph 127. Edited by Ashery RS. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1992Google Scholar

79. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216–231, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80. Barry KL, Zeber JE, Blow FC, et al: Effect of strengths model versus assertive community treatment model on participant outcomes and utilization: two-year follow-up. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:268–277, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

81. Levy JA, Gallmeier CP, Weddington WW, et al: Delivering case management using a community-based service model of drug intervention, in Progress and Issues in Case Management, NIDA Research Monograph 127. Edited by Ashery RS. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1992Google Scholar

82. National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors: Certification Commission Oral Exam Guidelines. Arlington, Va, National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors, 1986Google Scholar

83. California Addiction Technology Transfer Center: Addiction Counseling Competencies: The Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes of Professional Practice. La Jolla, Calif, California Addiction Technology Transfer Center, 1997Google Scholar

84. Ontwikkelcentrum Sociaal Verslavingsbeleid: Handreiking voor casemanagers in de sociale verslavingszorg. [Manual for Case Managers in Social Addiction Treatment.] Utrecht, Resultaten Scoren, 2003Google Scholar

85. Fiander M, Burns T: A Delphi approach to describing service models of community mental health practice. Psychiatric Services 51:656–658, 2000Link, Google Scholar

86. Wingerson D, Ries RK: Assertive community treatment for patients with chronic and severe mental illness who abuse drugs. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 31:13–18, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87. Powell S: Case Management: A Practical Guide to Success in Managed Care. Baltimore, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001Google Scholar

88. Block RI, Bates ME, Hall JA: Relation of premorbid cognitive abilities to substance users' problems at treatment intake and improvements with substance abuse treatment and case management. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 29:515–538, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

89. Vaughn T, Sarrazin MV, Saleh SS, et al: Participation and retention in drug abuse treatment services research. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 23:387–397, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar