Review of Literature on Aftercare Services Among Children and Adolescents

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Psychiatric hospital lengths of stay have decreased for children and adolescents, in part because of the presumption that aftercare services in the community are effective and accessible. This review critically examines the literature that pertains to the rates of aftercare service use, the effectiveness of aftercare services, and predictors of aftercare service use. METHODS: Studies were selected on the basis of MEDLINE and PsychINFO computer searches, covering the period between January 1992 and August 2003. Reports that were selected (N=21) included data on outpatient aftercare service use among youths who were aged 18 years and younger and who were discharged from child and adolescent inpatient facilities. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: A majority of youths received aftercare services after hospitalization, but many youths and families were not fully compliant with aftercare recommendations. Many youths and families continued to receive services up to three months after hospitalization. The literature documents only a small amount of evidence about the effectiveness of aftercare services, but the evidence suggested that aftercare services for youths with substance use problems may have beneficial effects. Few studies examined predictors of aftercare service use and discontinuation, but previous recent mental health service use and decreased family dysfunction appeared to be related to aftercare service use.

In this era of managed care, the lengths of psychiatric hospitalization for children and adolescents have shortened (1). Also, the focus of psychiatric hospitalization has shifted from comprehensive evaluation and treatment to brief intensive intervention, with discharges from hospitals often occurring as soon as psychiatrically disturbed youths are thought to be stable and to no longer represent an immediate danger to themselves or others (2). Psychiatric hospitalization is typically very intensive and restrictive, and helping youths to make the transition to outpatient care in the community as soon as it is feasible is consistent with the principles that are described in the Child and Adolescent Service System Program (3). Nonetheless, an underlying presumption exists that children and adolescents will be able to continue to receive and will benefit from outpatient aftercare services after hospitalization (4). Ideally, such outpatient aftercare services should continue and build on the treatment that was initiated in the hospital and, to the extent possible, help youths avoid the possibility of future hospitalization or more intensive care (4).

However, the rates of use of aftercare services and evidence for the effectiveness of these services have not been well documented or critically examined. In this regard, our review focuses on three questions about aftercare service use. First, what is known about the patterns of mental health service use among children and adolescents after their hospitalization? Second, does participation in mental health services after hospitalization actually improve outcomes for children and adolescents? Third, what factors are predictive of mental health service use or discontinuation after hospitalization?

Methods

In our literature review, aftercare services refer to outpatient mental health care and related services that are received after discharge from an inpatient hospitalization. This definition of aftercare services is intentionally broad so as to include not only mental health specialty services but also the informal services that are received by youths in a variety of settings.

Studies initially were selected on the basis of MEDLINE and PsycINFO computer searches, covering the period between January 1992 and August 2003. The computer literature searches were conducted by using various parameters and steps. In the first step, the set of terms "inpatient or hospital or institution" was crossed (by using the Boolean logic term "and") with "psychiatric or mental or substance." In the second search, the set of terms "follow-up or followup or longitudinal" was crossed (by using the Boolean logic term "and") with "treatment or services or outpatient or appointment or therapy." A third search was conducted for articles that had any of the keywords "aftercare," "compliance," or "adherence." Articles that were found with either of the latter two searches were combined into a single set (by using the Boolean logic term "or"). This resulting larger set was then crossed (by using the Boolean logic term "and") with the results of the first search. The resulting group of articles was then restricted to those with youths aged from birth to 18 years as subjects and to those that were written in English. Studies that were identified from the bibliographies of the initial articles were also included.

Selected reports included data about the rates of outpatient aftercare service use among youths who were aged 18 years or younger and were discharged from child and adolescent psychiatric and substance abuse inpatient units. Articles included data that were obtained only from the United States, as systems of care differ between the United States and abroad. Because of the limited number of studies that have examined common outcomes and predictor variables of aftercare service use, quantitative methods, such as meta-analyses, were not used in our review. Rather, our review is organized thematically, with attention drawn to the descriptive patterns or commonalities that emerged across studies.

Results

A total of 21 reports were reviewed. The reports are discussed here from three perspectives: patterns of aftercare service use, the effectiveness of these services, and predictors of use.

Patterns of use

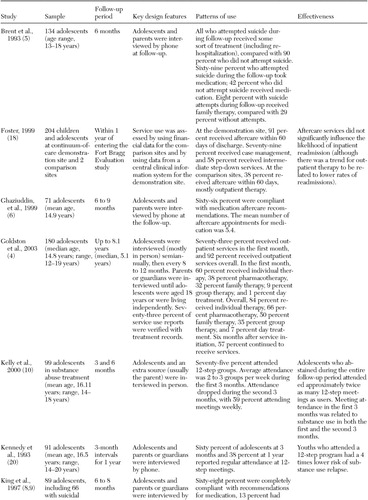

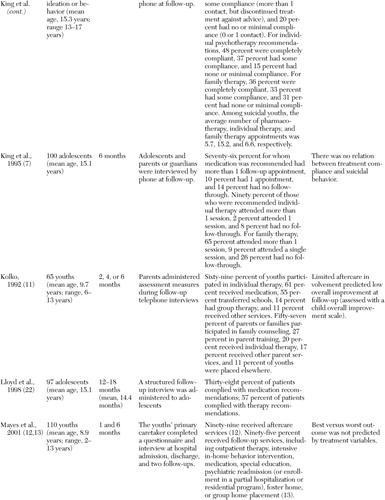

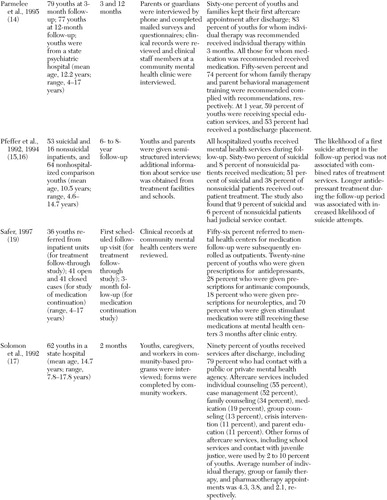

The studies that identified rates of initiation of aftercare services or rates of compliance with aftercare services among youths are summarized in Table 1. As the table shows, most studies that examined rates of initiation of aftercare services found that approximately two-thirds or more of the youths received at least some services after being discharged from the hospital (4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17). Notable exceptions included the rate of aftercare service use that was reported at the comparison sites in the Fort Bragg Evaluation study (18) and the rates of follow-through with appointments for medication management at community mental health centers that were reported in another study (19). The decreased rate at the comparison sites in the Fort Bragg Evaluation study (18) may be attributable in part to the fact that data on aftercare services were collected by using financial records; however, data on aftercare service use that were obtained outside of the CHAMPUS system would not have been recorded. In the other study, the decreased rate may be partially related to the fact that rates of aftercare service use were estimated from clinical records at the community mental health centers (19). This procedure also may have resulted in conservative estimates of aftercare service use, particularly if youths and families obtained services outside the mental health centers or if they obtained services that were not originally recommended.

Although a majority of youths in the studies that we reviewed eventually received at least some aftercare services, they did not always receive their first services promptly or when it was first intended. For example, Goldston and colleagues (4) found that most outpatient mental health service use (73 percent of 80 youths) was initiated within the first month after discharge. However, adolescents and families continued to seek new services even after that point. More specifically, 92 percent of the youths ultimately received some form of outpatient care up to eight years after their hospitalization. In a similar manner, Parmelee and colleagues (14) found that only 61 percent of 79 youths and families kept their first scheduled aftercare appointment, but a greater proportion of youths (83 percent) eventually received services.

Several investigators described specific types of aftercare services that were received by youths (4,5,11,14,17). Across studies, individual therapy seemed to consistently be among the most commonly used—if not the most commonly used—and recommended type of aftercare service (4,7,9,11,17). Pharmacotherapy and family therapy also appeared to be highly used and recommended, although rates of the use of these services appeared to differ somewhat across sites and studies (4,5,7,8,9,11,14,17). Group therapy, including self-help groups, appeared to be used less frequently among child and adolescent psychiatric patients, although participation in groups appeared to be commonly recommended for youths with alcohol and substance use problems (10,20,21). Few studies documented mental health services that were received through the schools or juvenile justice system; although it is clear that youths who were discharged from psychiatric hospital settings often received school services and have contact with the legal system (14,15,17). At least one study suggested that a majority of youths received multiple forms of aftercare services (4). However, only one of the naturalistic follow-up studies examined the extent of case management among formerly discharged patients (17), despite its potential utility in improving coordination and continuity of care after discharge (18).

Even when youths and families received aftercare services, they often did not participate in these services for as long as recommended (7,8,9,22). Across studies that examined compliance with the three types of therapy, pharmacotherapy and individual therapy appeared to be associated with higher rates of compliance than family therapy (7,8,9). However, rates of compliance with recommended pharmacotherapy appeared to vary across studies and sites (6,7,8,9,19,22).

Few studies examined the actual number of appointments of aftercare services that were kept by youths and families, regardless of the recommended number of appointments. Particularly for individual therapy, data for the number of appointments that were kept have varied widely. For example, Solomon and Evans (17) reported that 20 youths who were discharged from a state psychiatric hospital attended an average of 4.3 individual therapy appointments in two months. In contrast, King and colleagues (9) reported that among 61 suicidal youths, the average number of individual therapy sessions was 15.2 in six months. The extent to which these differences reflected the differing lengths of follow-up or reflected sample characteristics is unclear. The number of pharmacotherapy visits was more consistent across studies (6,9,17). For example, in the two studies with the largest samples that reported the number of aftercare service visits, the number of pharmacotherapy visits ranged from 5.4 (N=77) (6) to 5.7 (N=51) (9).

In terms of length or duration of treatment, Spirito and colleagues (23) found that among 84 youths who received psychotherapy after discharge from either a general or a psychiatric hospital, 57 percent were classified as having had at least monthly or bimonthly sessions three months after discharge. For a mixed psychiatric inpatient sample, Goldston and colleagues (4) estimated that between 71 percent and 81 percent of adolescents who received individual therapy (N=148), family therapy (N=89), group therapy (N=59), or pharmacotherapy (N=116) continued in treatment three months after service initiation. Similarly, in two samples from inpatient substance abuse treatment facilities, attendance in 12-step groups three months after discharge was reported by 60 percent (N=91) (20) to 75 percent (N=99) (10) of youths.

In sum, it appears that most youths who were discharged from inpatient settings received at least some aftercare services. Individual therapy, pharmacotherapy, and family therapy appear to be the most commonly used aftercare services. Regardless of initial use of services, estimates of the length of aftercare services varied quite widely among studies. Missed appointments and lack of full compliance with aftercare recommendations appeared to be common. Nonetheless, findings from several studies converge in suggesting that a majority of youths receiving aftercare service continued to do so three months after hospital discharge.

Effects of use

To examine the effectiveness of aftercare services, a minimum requirement is that a comparison be made between a sample that received aftercare services and a sample that did not receive those same services. Or a comparison could be made between samples that received different amounts or different types of aftercare services. Without such comparisons it is impossible to determine whether the effects are a result of participation in the treatment program per se or are simply a result of the passage of time, the increasing maturity of the youths who are being followed, an artifact of the manner in which outcomes are assessed, or a particular characteristic of the target population that is being followed.

Randomized controlled trials in which youths (or sites) are assigned to receive aftercare services or no aftercare services, different types of aftercare services, different forms or frequencies of aftercare services, or specialized aftercare services compared with treatment as usual would be the ideal approach to examining the effectiveness of aftercare services. However, restricting recommended treatment choices—as in the case of assigning a youth to aftercare services or to no aftercare treatment—is not ethically justifiable. Thus we were not able to locate any randomized controlled trials of aftercare services among children or adolescents who were previously hospitalized.

Given the dearth of controlled studies, investigators have had to infer information about the effectiveness of aftercare services from studies of youths who either complied or did not comply with aftercare recommendations, from studies of youths who received either more or fewer aftercare services, or from naturalistic prospective studies in which some youths received specific aftercare services and others did not. The results of such studies may provide indirect indications of the effectiveness of aftercare services, but they are tempered by the fact that youths and families who self-select or remain in aftercare services or who are compliant with aftercare treatment recommendations may differ in important ways from youths and families who do not participate in aftercare services.

With that caveat, we found six studies that examined whether aftercare service use was associated with reduction in severity of symptoms. These studies are summarized in Table 1. Three of these studies focused on outcomes among youths who were hospitalized in general psychiatric settings, whereas the other three focused on outcomes among youths who received inpatient substance abuse treatment. For the first three studies, no clear conclusions can be reached about whether a relationship exists between aftercare service use and outcomes. One of these studies found that aftercare service use or involvement was not related to suicide attempts (7). In another study, rates of combined treatment were also not found to be associated with the likelihood of suicide attempts, but antidepressant use during follow-up was related to increased suicide attempts (16). In an additional study, limited involvement in aftercare services predicted low overall improvement at follow-up (11). By contrast, all three studies of youths who were discharged from substance abuse facilities found that greater involvement in aftercare services was related to lower risk of substance use or greater likelihood of abstinence (10,20,21).

Although studies that focus on symptomatic improvement obviously are important, Hoagwood and Koretz (24) suggested that efforts to assess the impact of mental health interventions should also focus on other domains, such as level of functional impairment, consumer perspectives, environmental contexts, and service systems. Nonetheless, only one study that we found examined the effects of aftercare service use on functional impairment (12), and we did not find any studies that examined the effect of aftercare service use on consumer perspectives, such as patient or family satisfaction, or on environmental contexts, such as the quality of family and peer relationships. The importance of assessing the impact of interventions on customer satisfaction was illustrated by findings from the Fort Bragg Evaluation study in which the provision of a case manager and continuum of clinical services did not necessarily reduce costs for enrolled families, but it did result in greater satisfaction among those who received the services (25).

The Fort Bragg Evaluation study was the only study that we found that examined the effects of aftercare services on service systems, such as the rates of rehospitalization or out-of-home placement (18). The Fort Bragg Evaluation study showed that aftercare services did not appear to be related to the likelihood of rehospitalization. The paucity of studies that we found that examined the effects of aftercare services is alarming, given the particularly high rate of rehospitalization and out-of-home-placement among youths who were hospitalized previously. For example, Arnold and colleagues (26) examined data for 180 psychiatrically hospitalized youths and found that 44 percent had one or more rehospitalizations. Of these youths, 19 percent had been rehospitalized within six months after discharge, and 23 percent were rehospitalized on multiple—between two and 13—occasions.

Predictors of use and discontinuation

Andersen and Newman (27) proposed a framework for viewing health service use that suggests an interaction among predisposing factors, enabling factors, and perceived need in the use of services. In this model, predisposing factors—such as demographic characteristics, social structure, and health beliefs and attitudes—increase the likelihood that treatment will be considered a viable option for persons who are faced with illness. Enabling and impeding factors are personal, family, or community resources or variables that affect the likelihood that patients or families will be able to obtain and use services. Perceived need refers to the perception of the patient, family, or experts as to the severity of the illness. In the latest version of this model, these factors influence each other and work as a whole in affecting service use (28). This model provides a useful framework within which to review current research.

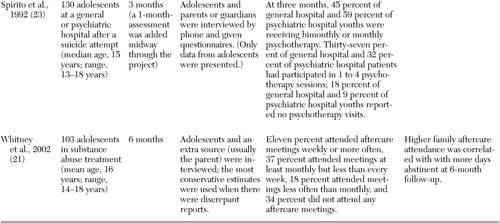

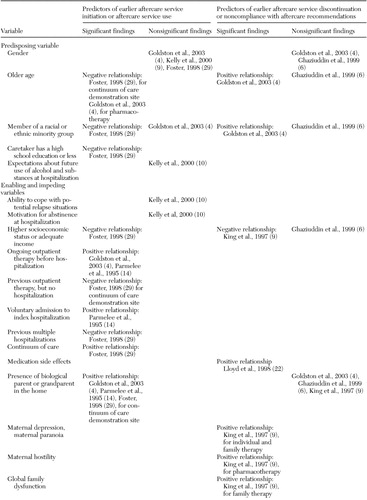

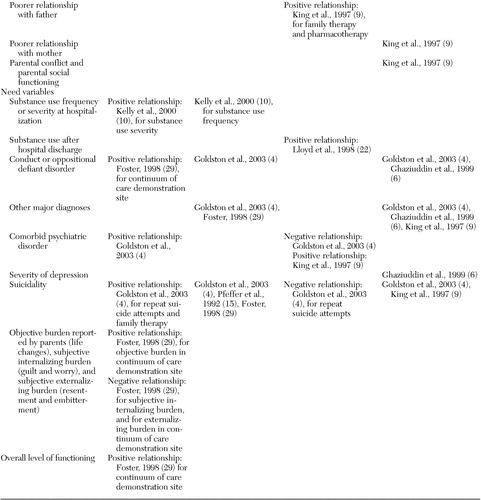

As can be seen in Table 2, the number of studies about predictors of initial use and discontinuation of aftercare services is quite limited in the sense that few variables have been examined in more than two studies. Nonetheless, several identifiable trends or replicated findings in the literature are noteworthy. For example, across four studies it appeared that gender did not influence whether youths entered into or remained in aftercare services (4,6,10,29). On the other hand, it appears that younger age may be related to aftercare use. In one study, younger age was related to aftercare use in the first 30 days after discharge, primarily for pharmacotherapy (4). In another study, younger age was related to earlier use of aftercare services at the continuum of care demonstration sites in the Fort Bragg Evaluation study (29). Also, findings have been mixed about whether younger age was related to longer use of or compliance with recommended services (4,6). Inconsistencies have been found for whether there is a relationship between race or ethnicity and use of aftercare services. However, studies have suggested that youths from minority groups may enter aftercare services at a slower rate (29) and that they may not remain in aftercare services as long as other youths (4). Such findings, if replicated, would be consistent with data that suggest that minority youths with psychiatric disorders may receive fewer mental health specialty services in the community than other youths (30).

Enabling and impeding factors may also be important predictors of aftercare service use. For instance, one study found that history of outpatient therapy, but not hospitalization, was associated with longer time until aftercare follow-up when there was an adequate continuum of care (29). However, this study did not describe when these past outpatient contacts occurred, and it is possible that recent contacts with mental health services may have a more facilitative effect in aftercare use. For example, in two studies, being in outpatient therapy just before hospitalization appeared to increase the likelihood of entering aftercare services or continuing in outpatient therapy after hospitalization (4,14). Presumably, youths and families who were engaged in treatment just before hospitalization already had overcome some of the barriers to gaining access to outpatient services (31). In addition, the results from the Fort Bragg Evaluation study suggest that having an adequate continuum of care and case manager services increases the likelihood of receiving aftercare services earlier after discharge—a 16-fold increase after other variables were considered (29). In addition, much like the finding that outpatient therapy before hospitalization increased the likelihood of aftercare service use, having adequate coordination and continuum of care may reduce barriers to entering outpatient treatment after hospitalization. Other service system variables—such as type of insurance coverage, aspects of managed care, wait list for new appointments, scheduling practices of service systems, availability of appointments, restrictiveness of policies for third-party payer sources, and accessibility of service locations—apparently have not been examined in relation to the likelihood of youths' gaining access to care after hospitalization.

Goldston and colleagues (4) found that the presence of at least one biological parent or grandparent in the home was associated with greater access to aftercare services in the first month after hospitalization. At the continuum of care demonstration site, Foster (29) found greater aftercare service use when a father was in the home. Logan and King (32) pointed out that parental figures have important roles in recognizing the need for treatment and gaining access to care for children and adolescents. One study in particular suggested that less compliance with aftercare recommendations may be related to family problems; maternal depression, hostility, and distrust; and a poor relationship between adolescent and father (9). Such findings suggest that parental problems and difficulties in relationships with parents interfered with follow-through with aftercare recommendations or the recognition of need for aftercare services. Poor parent-child relationships and parental psychological problems may, of course, be interrelated with the problems that are experienced by the child or adolescent. Youths' mental health and behavioral problems may have an impact on others, just as youths' problems may be triggered, exacerbated, or maintained by what is going on in the family.

In Anderson and Newman's model (27), perceived need and illness severity are potential correlates of health service use. There was no strong or consistent evidence that suggested that the presence of a psychiatric disorder, psychiatric comorbidity, or symptoms per se is related to aftercare service use (6,4,29). Similarly, history of a single suicide attempt, recent suicidality, and even severity of suicidality did not appear to be related to aftercare service use (4,15,29), although repeat suicide attempts were related in one study to longer time in aftercare services and greater use of family therapy (4). In an inpatient sample—which by definition is characterized by a high degree of psychiatric problems—psychiatric disorders or symptoms may not differentiate youths in terms of their subsequent service use as much as other factors.

Another possible indicator of need is caregiver burden. However, only one study examined the relationship between the burden posed by a child's psychiatric problems and its relationship to aftercare service use (29). Paradoxically, that study found that objective burden—which was reflected in difficulties or changes in routine or lifestyle caused by the child's problems—was related to use of aftercare services sooner after discharge. However, that study also found that more subjective indexes of burden—for example, guilt or worry—were related to less timely service use. Further studies are needed to examine the relationship between the burden that is caused by a child's psychiatric problems and how the burden affects the likelihood of gaining access to needed services.

Discussion

Use of aftercare services is presumed to reduce the likelihood of further hospitalization and to be associated with better outcomes. In our review of 21 reports, we found none that demonstrated that aftercare services reduce the likelihood of rehospitalization or increase the time between hospitalizations. Mixed findings exist about whether aftercare service use is associated with better outcomes in terms of psychiatric symptoms, although aftercare service use does appear to be related to less substance abuse among youths who have been in substance abuse treatment.

One difficulty in using naturalistic studies to examine the relationship between aftercare service use and symptom outcome or functional impairment is the fact that some of the most severely disturbed or impaired youths may be likely to have both ongoing mental health contacts and the poorest outcomes. Randomized controlled trials—which could compare the relative effectiveness of different types of aftercare services—in which youths are assigned to treatment as usual after hospitalization or to one or more specific programs of aftercare—are noticeably absent in the literature.

Although the figures vary, the extant studies suggest that a majority of youths who are hospitalized in psychiatric settings may receive at least some mental health services after discharge. Unfortunately, even when youths initially receive aftercare services, studies suggest that many of them may not remain in these services as long as recommended by their clinicians. This finding presents an additional challenge when trying to determine the relationship between aftercare use and outcomes related to use. Patients who pursue and follow through with aftercare services may be a unique subset of patients and may differ in important ways from those who do not follow up with recommendations for clinical care. Possibly the same patients who do not follow through with clinical services also do not follow through with research follow-up appointments.

Even when youths remain in aftercare services, most do not receive the same quantity of services that they received while they were hospitalized. Abrupt transitions in level of services can occur when youths are shifted immediately from a restrictive environment of constant monitoring and intensive treatment to weekly or less frequent outpatient therapy sessions. More studies that focus on partial hospitalization, day treatment, and intensive outpatient treatment are needed to ascertain the degree to which these programs can improve outcomes by strengthening the continuum of care and reinforcing the need for continued follow-up services after psychiatric hospitalization.

Improved methods are also needed for the measurement of service use after hospitalization. The comparability and precision of most estimates of services that are received have been limited by a number of factors, including the varying definitions of aftercare services, the lack of standardized instruments with established reliability and validity for measuring service use, and the use of single-occasion follow-up research assessments. In only two studies were data collected at more than one follow-up assessment (4,14). Only three studies used longitudinal data analytic techniques to examine the amount of time until patients received services after hospitalization (4,15,29). No studies investigated whether or not a critical period exists in which a first aftercare appointment is crucial to the likelihood of continuing outpatient care. Prospective, repeated assessment studies that use assessment instruments with established reliability and validity are needed to accurately characterize patterns of treatment as typically received by children and their families after hospitalization.

Relatively little is known about the predictors of mental health service use and continuation of services by youths after hospitalization. Nevertheless, recent outpatient mental health service use, presence of a parent or grandparent in the home, and a lower level of family dysfunction and of parental psychiatric problems all appear to be related to greater use of aftercare services. Future prospective studies should address the effectiveness of aftercare service use across multiple domains, the patterns of use of different types of aftercare services, and the predictors of aftercare service use, including parental burden, parental and youth expectations, case management, and characteristics of local service delivery systems.

Conclusions

In sum, the rates, effects, and predictors of aftercare service use for youths have been largely understudied. In addition, considerable variation exists in the methods used in the studies reviewed, making it more difficult to reach conclusions about predictors and outcomes of aftercare service use. Moreover, the extant studies have generally not evaluated the quality of the mental heath services provided. In many of the naturalistic studies it was not clear what steps were taken to increase compliance with follow-through of aftercare services. Thus it is very difficult to be specific as to how the results of existing studies may guide clinical practice and increase the rates and positive outcomes of aftercare service use among previously hospitalized youths. Furthermore, consistent with epidemiologic data (33), several areas—for example, the school system, juvenile justice programs, and social service programs—exist where youths receive aftercare services other than traditional mental health specialty services, but data on these services are typically not reported. Hence, the effectiveness, rates of use, and predictability of such aftercare services are unclear and should be the focus of future studies. In this context, it is of note that a number of hospitals now have systems for assessing aftercare service use as quality assurance indicators. Such data could be examined to yield useful information about both formal and informal mental health services after hospitalization across sectors of care.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant MH-63433 from the National Institute of Mental Health, which was awarded to the senior author, and grants MH-54818 and MH-66252 from the National Institute of Mental Health, which were awarded to the second author.

Dr. Daniel, Dr. Harris, Dr. Kelley, and Dr. Palmes are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27157-1087 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Goldston is with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina.

|

Table 1. Patterns of use and effectiveness of aftercare services for children and adolescents that were described in 20 reports

|

Table 1b.

|

Table 1c.

|

Table 1d.

|

Table 2. Predictors of aftercare service use and discontinuation among youths that were found in eight reports

|

Table 2b.

1. National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems Annual Survey Reports. Washington, DC, National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems, 1988 through 2000Google Scholar

2. Allen M: When is psychiatric hospitalization required? in Controversies in Managed Mental Health Care, Edited by Lazarus A. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

3. Stroul B, Friedman R: A System of Care for Severely Emotionally Disturbed Children and Youth. Washington, DC, Child and Adolescent Service System Program Technical Assistance Center, 1986Google Scholar

4. Goldston D, Reboussin B, Kancler C, et al: Rates and predictors of aftercare services among formerly hospitalized adolescents: a prospective naturalistic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:49–56, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Brent D, Kolko D, Wartella M, et al: Adolescent psychiatric inpatients' risk of suicide attempt at 6-month follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:95–105, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ghaziuddin N, King C, Hovey J, et al: Medication noncompliance in adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 30:103–110, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. King C, Segal H, Kaminski K, et al: A prospective study of adolescent suicidal behavior following hospitalization. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 25:327–338, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

8. King C, Hovey J, Brand E, et al: Prediction of positive outcomes for adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:1434–1442, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. King CA, Hovey JD, Brand E, et al: Suicidal adolescents after hospitalization: parent and family impacts on treatment follow-through. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:85–93, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kelly J, Myers M, Brown S: A multivariate process model of adolescent 12-step attendance and substance use outcome following inpatient treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behavior 14:376–389, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kolko D: Short-term follow-up of child psychiatric hospitalization: clinical description, predictors, and correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:719–727, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Mayes S, Calhoun S, Krecko V, et al: Outcome following child psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 28:96–103, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Mayes S, Krecko V, Calhoun S, et al: Variables related to outcome following child psychiatric hospitalization. General Hospital Psychiatry 23:278–284, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Parmelee D, Cohen R, Nemil M, et al: Children and adolescents discharged from public psychiatric hospitals: evaluation of outcome in a continuum of care. Journal of Child and Family Studies 4:43–55, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Pfeffer C, Peskin J, Siefker C: Suicidal children grow up: psychiatric treatment during follow-up period. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:679–685, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Pfeffer C, Hurt S, Kakuma T, et al: Suicidal children grow up: suicidal episodes and effects of treatment during follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33:225–230, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Solomon P, Evans D: Use of aftercare services by children and adolescents discharged from a state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:932–934, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Foster E: Do aftercare services reduce inpatient psychiatric readmissions? Health Services Research 34:715–736, 1999Google Scholar

19. Safer D: Changing patterns of psychotropic medications prescribed by child psychiatrists in the 1990s. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 7:267–274, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kennedy B, Minami M: The Beech Hill Hospital/Outward Bound Adolescent Chemical Dependency Treatment Program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 10:395–406, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Whitney S, Kelly J, Myers M, et al: Parental substance use, family support, and outcome following treatment for adolescent psychoactive substance use disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse 11:67–81, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Lloyd A, Horan W, Borgaro S, et al: Predictors of medication compliance after hospital discharge in adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 8:133–141, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Spirito A, Plummer B, Gispert M, et al: Adolescent suicide attempts: outcomes at follow-up. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 62:464–468, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Hoagwood K, Koretz D: Embedding prevention services within systems of care: strengthening the nexus for children. Applied and Preventive Psychology 5:225–234, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Bickman L, Guthrie P, Foster E, et al: Evaluating Managed Mental Health Services: The Fort Bragg Experiment. New York, Plenum, 1995Google Scholar

26. Arnold E, Goldston D, Ruggiero A, et al: Rates and predictors of rehospitalization among formerly hospitalized adolescents. Psychiatric Services 54:994–998, 2003Link, Google Scholar

27. Andersen R, Newman J: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Quarterly 51:95–124, 1973Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Andersen R: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

29. Foster E: Does the continuum of care improve the timing of follow-up services? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:805–814, 1998Google Scholar

30. Angold A, Erkanli A, Farmer E: Psychiatric disorder, impairment, and service use in rural African American and white youth. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:893–901, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Kazdin A: Perceived barriers to treatment participation and treatment acceptability among antisocial children and their families. Journal of Child and Family Studies 9:157–174, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Logan D, King C: Parental facilitation of adolescent mental health service utilization: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 8:319–333, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Burns B, Costello E, Angold A, et al: Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs 14(3):147–159, 1995Google Scholar