Unusual Case Report: Three Cases of Psychiatric Manifestations of Neurosyphilis

Abstract

Along with the advent of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) came a worldwide resurgence of syphilis. The later stages of syphilis, especially neurosyphilis, may present with symptoms of virtually any psychiatric disorder. The authors present three cases of neurosyphilis diagnosed at the Center for Psychiatric Medicine of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where the patients presented with overwhelmingly psychiatric manifestations. The authors recommend that clinicians have a high index of suspicion of neurosyphilis, which may have an exclusively psychiatric presentation.

Along with the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) there has been a worldwide resurgence of syphilis (1). Neurosyphilis may present as virtually any psychiatric disorder, including personality disorder, psychosis, delirium, and dementia (2). Here we report three cases of neurosyphilis among persons who presented as psychiatric patients during a four-year period at the Center for Psychiatric Medicine of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Psychiatric manifestations of neurosyphilis

A review of the literature indicates various psychiatric presentations of neurosyphilis (3). A significant number of patients with neurosyphilis present with dementia, which has an insidious onset leading to a progressive global deterioration in intellectual functioning, with episodes of delirium. Lesions in the temporoparietal lobes among patients with neurosyphilis have a significant correlation with low scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (4).

About 27 percent of patients with general paresis present with depression characterized by psychomotor retardation, melancholia, and suicidal ideation. Mania may also be present, characterized by euphoria, irritability, grandiosity, delusions, loose associations, rambling and pressured speech, flight of ideas, incoherence, and hyperactivity (5). Another manifestation of neurosyphilis is psychosis, which can be indistinguishable from psychotic features of schizophrenia with acute or insidious onset. Lesions in the frontal lobes seen among patients with neurosyphilis correlate with high scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (4).

Patients may also present with altered personality, which is characterized by antisocial behavior, explosive temper, hostility, emotional lability, affective instability, anhedonia, social withdrawal, decreased attention to personal affairs, unusual giddiness, histrionicity, and hypersexuality (2). Substance-related presentations are also seen among patients with neurosyphilis, including excessive drinking of alcohol, low tolerance of alcohol, and features suggestive of Korsakoff's psychosis. Another manifestation is sexual dysfunction: impotence has been reported in tabetic neurosyphilis. Finally, a diagnosis of neurosyphilis must be considered when possible causes of delirium are excluded, which often heralds the acute onset of general paresis.

Case reports

Mr. A, a 45-year-old African-American man with no psychiatric history, was admitted to the Center for Psychiatric Medicine of the University of Alabama at Birmingham with violent behavior and hyperreligiosity and for striking staff members at a residential substance abuse treatment facility. His physical and neurologic test results were normal. Laboratory investigation and a urine drug screen were negative, as were tests for HIV antibodies.

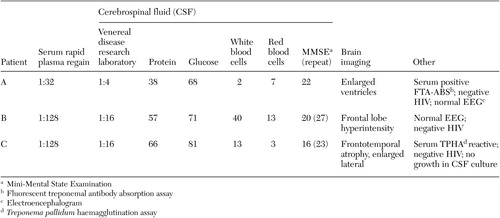

A computed tomography scan of the brain showed enlargement of the third and lateral ventricles with some sulcal widening. The results of Mr. A's serum and cerebrospinal fluid serologic tests for syphilis are presented in Table 1, along with those of the other patients whose cases are reported here. Interestingly, Mr. A's CSF protein, glucose, and cell counts were within the normal range, which, although unusual, can occur in the late stages of syphilis (6). The patient's affect, speech, behavior control, and thought processes all improved soon after initiation of treatment with intramuscular procaine penicillin, although his Folstein's MMSE score remained at 22. (Possible scores range from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating greater impairment.)

Mr. B, a 40-year-old African-American man with no psychiatric or medical history, was brought to the university's psychiatric emergency department after paramedics found him lying in the street "playing dead." He stated that he had had no "problems" until three months ago, when he felt guilty about an affair he had had with a woman at his church and started to believe that he was being "punished by God for sinning." He thought people were trying to harm him and to poison his food and water with Pine-Sol cleaning liquid. He was admitted to the university's psychiatric emergency department because of paranoid delusions.

The patient reported no auditory or visual hallucinations. His MMSE score on admission was 20. The results of his physical and neurologic examinations were normal, and his laboratory tests and urine drug screen were negative, as were tests for HIV antibodies. Cranial MRI showed small flare hyperintensities in the left and right frontal white matter. The infectious diseases department was consulted, and the patient improved remarkably after treatment with intravenous penicillin. A repeat MMSE yielded a score of 27.

Mr. C, a 51-year-old white man, was brought to the university involuntarily because of personality changes and bizarre behavior. He had worked for many years as a construction worker but had lost interest in his job and had quit about six months earlier. He would wander the highways picking up trash. He became increasingly more apathetic and uncommunicative. He would often refuse to change his clothes, bathe, or maintain even minimal hygiene. He had recently become incontinent. His physical examination results were normal except for neurologic tests, which showed a wide-based gait with 4+ deep tendon reflexes of biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, and patellar. Inspection of the penis revealed two circular areas of hyperpigmentation. Tests for HIV antibodies were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed deep atrophy with symmetric enlargement of the lateral ventricles. Approximately five days into treatment with ceftriaxone, the patient began to show increased interaction, improved mood, better personal hygiene, and goal-directed speech. Approximately ten days into treatment he started to regain continence, although he had occasional relapses. A repeat MMSE yielded a score of 23.

Discussion

The three patients described here presented with multitudes of psychiatric signs and symptoms. Patients with neurosyphilis can also present with many different physical or neurologic symptoms that lead to admission or follow-up at a medical or neurology unit. What was interesting about the three cases discussed here was that all patients showed exclusively psychiatric manifestations, leading to direct admission to a psychiatric unit rather than a medical or neurology unit with psychiatric consultation. The point we are trying to emphasize here is that clinicians—including internists and neurologists, and especially psychiatrists—need to have a high index of suspicion of neurosyphilis, which may have an exclusively psychiatric presentation rather than medical or neurologic symptoms, because, despite a dramatic decline in the incidence of neurosyphilis since the early 20th century, new cases are still occurring. Without such an awareness on the part of clinicians, not only will this diagnosis be missed, but an extensive and unnecessary laboratory investigation—and its associated tremendous costs—will follow.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of neurosyphilis (7), all three of the patients reported here had neurosyphilis. Results of the patients' brain imaging studies, including enlarged third and lateral ventricles and frontal and temporal lobe atrophy, are also consistent with findings of other investigators (8). Cortical atrophy also explains the low MMSE scores of the three patients and again is a finding consistent with those of other investigators (8). All three patients improved after antibiotic therapy.

It is noteworthy that all these patients were HIV negative. The natural history of neurosyphilis can be altered by concurrent HIV infection (9). Interpretation of serologic test results can also be confusing, because patients with both HIV and syphilis have higher titers on nontreponemal tests than do patients with syphilis alone (10). Because the clinical presentations of the three patients were not clouded or compounded by concurrent HIV infection, we can strongly argue that patients with neurosyphilis can present with predominantly psychiatric symptoms. We recommend that a diagnosis of neurosyphilis be considered among patients who have unusual psychiatric symptoms and that the HIV status of all such patients be checked.

Conclusions

Clinicians, especially psychiatrists, need to remain aware of the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of neurosyphilis, because many patients with neurosyphilis present with subtle personality changes, dementia, or delirium, which creates a diagnostic dilemma. Therefore, serologic tests for syphilis should be a routine part of the evaluation of patients who present with neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Dr. Sobhan is affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Faith Regional Health Services, 1500 Koenigstein Avenue, Suite 400, Norfolk, Nebraska 68701 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Rowe is with the department of psychiatry of Greil State Psychiatric Hospital in Montgomery, Alabama. Dr. Ryan is with the department of psychiatry of the University of Alabama in Birmingham. Dr. Munoz is with the department of psychiatry of the Birmingham Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital in Birmingham, Alabama.

|

Table 1. Laboratory and neuroimaging test results for three patients with neurosyphilis

1. Russouw HG, Roberts MC, Emsley RA, et al: Psychiatric manifestations and magnetic resonance imaging in HIV-negative neurosyphilis. Biological Psychiatry 41:467–473, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Roberts MC, Emsley RA: Psychiatric manifestations of neurosyphilis. South African Medical Journal 82:335–337, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

3. Scheck DN, Hook EW III: Neurosyphilis. Medical Clinics of North America 8:769–795, 1994Google Scholar

4. Kodama K, Okada SI, Komatsu N, et al: Relationship between MRI findings and prognosis for patients with general paresis. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 2:246–250, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Hoffman BF: Reversible neurosyphilis presenting as chronic mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 43:338–339, 1982Medline, Google Scholar

6. Jacobs RA: Infectious diseases: spirochetal, in Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment, 40th ed. Edited by Tierney LM, McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA. New York, Lange Medical Books, 2001Google Scholar

7. Luger AF, Schmidt BL, Kaulich M: Significance of laboratory findings for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. International Journal of STD and AIDS 11:224–234, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gliatto MF, Caroff SN: Neurosyphilis: a history and clinical review. Psychiatric Annals 31:153–161, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Flood JM, Weinstock HS, Guroy ME, et al: Neurosyphilis during the AIDS epidemic, San Francisco, 1985–1992. Journal of Infectious Disease 177:931–940, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hook EW III: Syphilis, in Infections of the Central Nervous System, 2nd ed. Edited by Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Durack DT. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1997Google Scholar