Effect of Managed Care on Access to Mental Health Services Among Medicaid Enrollees Receiving Substance Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Mental health services are important to treatment retention and positive outcomes for many clients of substance abuse treatment programs. For these clients the implementation of managed care should provide for continued or increased access to mental health treatment, rather than decreased access because of short-term, cost-reduction objectives. This study assessed whether converting Medicaid from a fee-for-service program to a capitated, prepaid managed care program affected access to mental health services among clients who were treated for substance abuse. METHODS: Medicaid enrollees who were being treated for substance abuse in Oregon were interviewed before beginning treatment and after six months of service. One cohort (N=53) was interviewed one to six months before the implementation of managed care, a second (N=66) was interviewed two years after the implementation, and a third (N=49) was interviewed three to four years after the implementation. Logistic regression analyses were used to identify whether the implementation of managed care, the psychiatric need of the client, and other client characteristics affected the receipt of mental health services during the first six months of substance abuse treatment. RESULTS: Clients in all three cohorts had similar characteristics. The implementation of managed care did not affect whether clients received mental health services. A baseline interview score that was derived from items in the Addiction Severity Index psychiatric section was the only client characteristic that predicted receipt of mental health services. CONCLUSIONS: Although this study was a naturalistic experiment with many methodologic flaws, it provided a unique opportunity to observe whether the introduction of managed care changed access to mental health services among Medicaid enrollees who were being treated for substance abuse.

The co-occurrence of substance use disorders and psychiatric disorders is extensive and complex (1,2). Substance use disorders have been related to personality disorders, anxiety and mood disorders, and psychotic disorders (3,4,5,6,7,8). Co-occurring disorders have been linked to noncompliance with treatment among adults who are chronically mentally ill (9,10) and to homelessness (11), violence (12,13), involvement with the criminal justice system (14), reinstitutionalization (15), and higher costs (16,17). Long-term course and treatment of both classes of disorders are greatly affected by their comorbidity (18,19,20,21). Clients in substance abuse treatment who receive mental health services and clients in mental health treatment who receive substance abuse services are more likely to fare better than those who do not receive such services (22,23,24). Therefore, access to mental health services promises better outcomes.

Effective diagnosis, clinical treatment, and programming for clients who have co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders remain challenging. However, financing and organizational variables are major concerns, because they facilitate or impede treatment (25,26,27,28). Capitation and prepayment theory of the 1980s initially promised to ensure that clients in substance abuse treatment would obtain the mental health services that they needed to shorten the course and reduce the severity of their disorders; these financing approaches offered an incentive to provide such services—avoidance of future costs—as well as an opportunity to do so—by uncoupling the fee from the services (29). Health maintenance and managed care theory promised organized, integrated delivery systems (30,31). Health advocates expected efficiencies, and insurers expected reduced expenditures as a result of elimination of unnecessary administrative and care costs (32). Because receipt of mental health services promises better outcomes for substance-abusing clients, incentives for managed care organizations should result in better access to mental health services. However, the operating expenses and, often, profits of the managed care organization emerged as an implicit priority (33). Mechanic and colleagues (34) described the complexities that appeared early in the national conversion to managed behavioral health care. The fundamental question is whether managed care achieved its other objectives—for example, profits, business expansion, career growth, and reduced premiums—at the cost of better access to mental health services and, therefore, better health outcomes.

Three aspects of financing outpatient behavioral health services changed from the 1970s to the 1990s in Oregon: source, form, and routing of payment. In the 1970s Oregon had global program budgets—that is, the state funded 100 percent of programs that provided an alternative to institutionalization and matched funds for locally supported generic outpatient services. In the 1980s the state developed slot funding mechanisms, which financed specific types and quantities of behavioral health services that had service use requirements. Toward the end of the 1980s Oregon implemented a fee-for-service payment mechanism to disburse state general funds and, increasingly, matching Medicaid federal funds to counties by way of omnibus contracts. Counties then delivered services directly or subcontracted with provider agencies.

Beginning in 1994 all of Oregon's health services that were funded by Medicaid began to be converted from a fee-for-service system to a capitated payment system—that is, the managed care organization was paid a fixed amount per covered person regardless of the actual number or nature of services provided. This capitated system was implemented under the Oregon Health Plan (OHP), a state managed care program. In May 1995 Oregon became one of the first states to implement capitated financing for Medicaid substance abuse treatment services, including regular outpatient, intensive outpatient, and methadone treatment. Although implementation of the OHP was complex (35), the period before May 1995 may be considered pre-managed care and the period after May 1995 may be considered post-managed care for the purpose of our study.

With the efficacy of mental health services for clients with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders well established in the research literature, the next issue that should be examined is access to mental health services. After access has been examined, other mental health service issues emerge, including amount, quality, coordination, and integration. Our study assessed whether converting Medicaid from a fee-for-service program to a capitated, prepaid managed care program affected access to mental health services among enrollees in Oregon who were treated for substance abuse.

Methods

Research design

Our research design took advantage of a naturalistic experiment and data collected for other purposes. Three different cohorts of Medicaid clients who were being treated for substance abuse were chosen because of similarities in the measures used and because of their timing: before versus after the OHP was implemented beginning in May 1995. The first cohort came from the Portland Target City Project in Multnomah County (36), and clients were initially interviewed from December 21, 1994, to April 13, 1995. Clients in the second cohort, also from the Portland Target Cities Project, were initially interviewed from March 11, 1997, to July 11, 1997. The third cohort came from the Managed Behavioral Health Care and Vulnerable Populations Study, and clients were initially interviewed from April 14, 1998, to March 8, 1999 (37,38). In our research design the first cohort was classified as pre-managed care and the second and third cohorts were classified as post-managed care.

Clients in the first two cohorts were interviewed shortly before treatment entry and again after six months of treatment. Clients in the third cohort were interviewed at the start of treatment and again after six months of treatment. In our research design "shortly before treatment entry" and "at the start of treatment" are considered equivalent observations.

All three cohorts were interviewed with the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), Version 5 (39,40), and other items. The six-month follow-up interview included items about access to mental health services during treatment. Our research design examined individual baseline demographic characteristics, ASI scores, and the type of Medicaid plan that was in effect when the client began treatment. Logistic regression analyses were used to identify whether these factors affected the receipt of mental health services during the first six months of substance abuse treatment.

There was no duplication of participants across cohorts. Details about sampling the Medicaid clients and survey procedures are provided elsewhere (36,37,38). Research protocols were approved by the institutional review board of record and by relevant state agency directors pursuant to Code of Federal Regulations 45, Part 46.116 (C) (1).

Measures

The ASI was administered at baseline and included sections on various problems: alcohol, drug, psychiatric, medical, legal, and employment. The psychiatric section included three sets of questions—whether the symptoms were present for two weeks or more, the severity of the symptoms, and the patient's desire for treatment—in eight symptom areas—depression, anxiety and tension, hallucination, confusion, control of violent impulse, thoughts of suicide, suicide attempt, and use of psychiatric medications.

For each ASI section a composite score was calculated, ranging from 0 to 1. The psychiatric composite score also incorporated three items that asked about earlier service use. Most of the composite scores were 0, and the remainder were clustered at the low end of the range—that is, the range of scores was skewed. Many statistical analyses assume that the data have a normal, not skewed, distribution. Therefore, the ASI composite scores were dichotomized to 0, no problems, or 1, any problems at all, and were treated as a binomial distribution. The dichotomized ASI psychiatric composite scores were used as indicators of clients' need for mental health services.

At the six-month follow-up interview, questions were asked of clients in the three cohorts about the types of mental health services that they received in the past six months. Two questions that were common to all three cohorts were, "In the past six months, did you receive mental health services?" and "In the past six months, were you treated as an outpatient for any psychological or emotional problems?" Whether clients answered yes or no to these two questions indicated whether they obtained mental health services.

Results

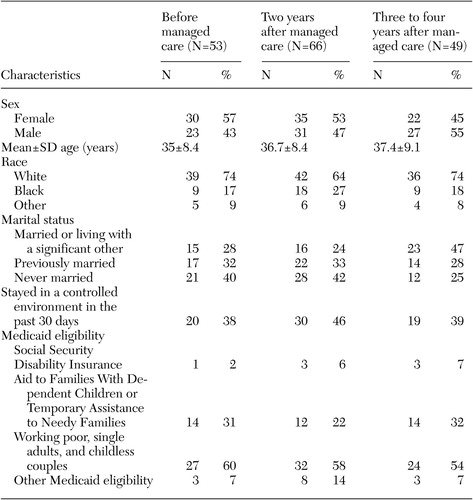

In a research design with different cohorts, it is critical to assess the cohorts' equivalence. For all 168 clients in the three cohorts a total of 87 clients (52 percent) were female and 117 clients (70 percent) were white. The mean±SD age of clients in the three cohorts was 36±8.6 years. A total of 54 clients (32 percent) were married or living with a significant other, 54 clients (32 percent) had previously been married, and 61 clients (36 percent) had never been married. Of the 144 clients who were eligible for Medicaid, 83 clients (58 percent) were eligible for Medicaid as working poor single adults or as childless couples, and 40 clients (28 percent) were eligible as covered families. A total of 69 clients (41 percent) had been in a controlled environment, for example, in jail or a hospital, in the 30 days before the baseline interview. No statistically significant differences were found among the cohorts for these characteristics, as shown in Table 1.

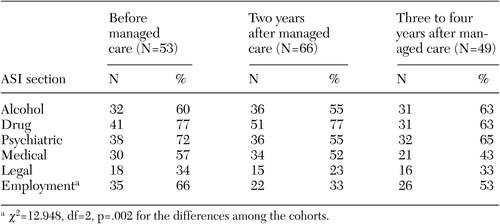

Table 2 shows the severity of problems that were assessed by the ASI at baseline. For all 168 clients in the three cohorts, 99 (59 percent) had alcohol problems, 123 (73 percent) had drug problems, 106 (63 percent) had psychiatric problems, 85 (51 percent) had medical problems, 49 (29 percent) had legal problems, and 83 (49 percent) had employment problems. Only one statistically significant difference was seen among cohorts in these domains. The first and third cohorts included significantly greater percentages of clients who had employment problems than did the second cohort.

Examining rates of access to mental health services among the pre- and post-managed care groups at the six-month follow-up interview determined whether managed care affected access to mental health services. Of the 53 clients who received pre-managed care, 16 (30 percent) received services from a mental health provider in the past six months and 11 (21 percent) were treated as an outpatient for any psychological or emotional problems in the past six months. Out of the 115 clients who received post-managed care, 29 (25 percent) received services from a mental health provider in the past six months and 22 (19 percent) were treated as an outpatient for any psychological or emotional problems in the past six months. The differences between the pre- and post-managed care groups were not statistically significant.

Logistic regression was used to determine whether demographic characteristics, ASI scores, and a dummy variable for pre- versus post-managed care status (in any combination) predicted whether mental health services were received. Clients' demographic characteristics included age, sex, race (nonwhite versus white), and whether the client lived in a controlled environment in the past 30 days. Medicaid eligibility categories were tested, but they were found to be insignificant. Because of missing data for this variable, we deleted Medicaid eligibility categories from the logistic regression.

Demographic characteristics and pre- versus post-managed care status (in any combination) failed to predict whether mental health services were received. For all three cohorts (N=168) the composite ASI psychiatric score at baseline predicted whether the client would receive mental health services during the first six months of substance abuse treatment (beta=1.692, odds ratio=5.433, Z=3.57, p<.001) and whether the client would be treated as an outpatient for any psychological or emotional problems during the first six months of substance abuse treatment (beta=2.048, odds ratio=7.749, Z=3.256, p<.001).

Discussion

This study assessed whether converting Medicaid from a fee-for-service program to a capitated, prepaid managed care program affected access to mental health services among clients who were treated for substance abuse in Oregon. Baseline demographic characteristics and the type of Medicaid financing plan did not predict which clients would receive mental health services. Only psychiatric need, as measured by the ASI, was associated with the use of mental health services.

Discussion with substance abuse treatment providers after a year of managed care (1996) indicated that some providers believed that managed care separated the substance abuse and mental health treatment systems (41,42). Nonetheless, providers reported having used creative approaches to serve clients with dual diagnoses, including consultations with mental health counselors, joint staffing (case conferences) with substance abuse and mental health counselors, and training staff about co-occurring disorders. Many providers indicated that they hired more counselors who had mental health training after the OHP was implemented because they had seen more clients with co-occurring substance abuse and psychiatric disorders in the past few years. Some providers had both mental health and substance abuse treatment counselors on site, offering separate but coordinated services; others said that only the funding was separate and that treatment was integrated. Some substance abuse treatment providers collaborated with mental health providers to meet the needs of clients, either by loaning substance abuse counselors to a mental health provider or by borrowing mental health counselors from mental health agencies.

Our study took advantage of a naturalistic experiment and used existing data. The small numbers of individuals in the cohorts attenuated statistical power. Furthermore, clients were interviewed in only one large metropolitan county. Although the measures and the timing of observations yielded a useful research design for a naturalistic study, the implementation of managed care was actually very complex. For example, a few follow-up interviews of pre-managed care clients took place shortly after managed care had been initiated. Further blurring the time boundaries were the omnipresent effects of "change anticipation," which occurred as a result of anticipating the implementation of the OHP and "implementation lag," which occurred as a result of all of the steps along the implementation critical path. Sampling across other programmatic and contextual variations was neither random, so the sample was not representative, nor controlled, so extraneous variance was not eliminated. Our measure of mental health services was insensitive to the amounts and kinds of service obtained, leaving us unable to go beyond the fundamental question of access to mental health services.

Altogether, many imperfections were present in our study. However, the data are valuable because they were collected at the critical time points in the conversion to managed care and because the same, well-established measures were used for all cohorts. This approach yielded some evidence in our answer to our study's fundamental question: access to mental health services neither decreased nor increased after the introduction of Medicaid managed care for substance abuse treatment. Further research is needed to replicate this finding in larger samples and to closely examine the relationships among financing and organizational variables, amount and quality of mental health services, coordination and integration of services, and client outcomes in Medicaid managed care programs for persons with co-occurring substance use problems and psychiatric conditions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01-AA11770 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; by grant 1-UR7TI1129401 from the systems improvement branch of the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; by cooperative agreement 93-196 from the state of Oregon; and by contract 87162 from the Oregon Department of Human Services. The authors thank Jane Grover, M.S., Katherine Laws, B.A., and Nancy Barron, Ph.D., for their work on study design and data collection.

Dr. Bigelow and Dr. McFarland are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 South West Sam Jackson Park Road, Gaines Hall 155, Portland, Oregon 97239 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. McCamant is a private consultant in Portland. Dr. Deck and Dr. Gabriel are with RMC Research Corporation in Portland.

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of three cohorts of Medicaid clients who were being treatedfor substance abuse

|

Table 2. Number of Medicaid clients who were being treated for substance abuse who had Addiction Severity Index (ASI) scores greater than zero at baseline

1. Kessler R, McGonagle K, Zhao, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Regier D, Farmer M, Rae D, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511–2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Schuckit MA, Hesselbrock V: Alcohol dependence and anxiety disorders: what is the relationship? American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1723–1734, 1994Google Scholar

4. Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bucholz KK, et al: The life-time rates of three major mood disorders and four major anxiety disorders in alcoholics and controls. Addiction 92:1289–1304, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Tsuang B, Cowley D, Ries R, et al: The effects of substance use disorder on the clinical presentation of anxiety and depression in an outpatient psychiatric clinic. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:549–555, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

6. Menzes P, Johnson S, Thornicroft G, et al: Drug and alcohol problems among individuals with severe mental illness in South London. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:612–619, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Brown SA, Inaba BA, Gillin JC, et al: Alcoholism and affective disorder: clinical course of depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:45–52, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Fowler I, Carr V, Carter N, et al: Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:443–455, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Pepper B, Ryglewicz H: Treating the young adult chronic patient: an update. New Directions for Mental Health Services 21:5–15, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Owen R, Rischer E, Booth B, et al: Medication noncompliance and substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:853–858, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Scott J: Homelessness and mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 162:314–324, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Steadman H, Mulvey E, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rasanen R, Tiihonen J, Isohanni M, et al: Schizophrenia, alcohol abuse, and violent behavior: a 26-year follow-up study of an unselected birth cohort. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:437–441, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Double-Jeopardy: Chronic Mental Illness and Substance Disorders. Edited by Lehman AF, Dixon LB. Langhorne, Pa, Harwood Academic Publishers, 1995Google Scholar

15. Cuffel B, Chase P: Remission and relapse of substance use disorders in schizophrenia: results from a one-year prospective study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:342–348, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wu L, Kouzis AC, Leaf PJ: Influence of comorbid alcohol and psychiatric disorders on utilization of mental health services in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1230–1236, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Harwood H, Fountain D, Livermore G: The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse in the United States 1992. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1998Google Scholar

18. Kozarie-Kovacic D, Folnegovic-Smalc V, Folnegovic Z, et al: Influence of alcoholism on the prognosis of schizophrenic patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 56:622–627, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Bartels S, Drake R, Wallach M: Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:248–251, 1995Link, Google Scholar

20. Ries R: Clinical treatment matching models for dually diagnosed patients. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 16:167–175, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Noordsy DL: Integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for severe psychiatric disorders. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 4:129–139, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Miller NS, Guttman JC: The integration of pharmacological therapy for co-morbid psychiatric and addictive disorders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 29:249–254, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Ritsher JF, Moos RH, Finney JW: Relationship of treatment orientation and continuing care to remission among substance abuse patients. Psychiatric Services 55:595–601, 2002Link, Google Scholar

24. Morse G, Calsyn R, Allen G, et al: Experimental comparison of the effects of three treatment programs for homeless mentally ill people. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:1005–1010, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Policy and financing issues in the care of people with chronic mental illnesses and substance use disorders, in Double Jeopardy: Chronic Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. Edited by Lehman AF, Dixon LB. Langhorn, Pa, Harwood Academic Press, 1995Google Scholar

26. National dialog on co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders. Rockville, Md, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Center for Mental Health Services, 1999. Available at www.nasadad.org/Departments/Research/ConsensusFramework/national_dialogue_on.htmGoogle Scholar

27. Minkoff K: Co-occurring psychiatric and substance disorders in managed care systems: standards of care, practice guidelines, workforce competencies, and training curricula. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998Google Scholar

28. Pepper B: Action for mental health and substance-related disorders: a conference report and recommended national strategy. Rockville, Md, National Advisory Council, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998Google Scholar

29. Wilson CV: Substance abuse and managed care in managed mental health care. New Directions for Mental Health Services 59:99–105, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. England MJ, Goff VV: Health reform and organized systems of care in managed mental health care. New Directions for Mental Health Services 59:5–12, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Shortell SM, Gillies RR, Anderson DA: The new world of managed care: creating organized delivery systems. Health Affairs 13(5):46–64, 1994Google Scholar

32. Iglehart JK: Managed care. New England Journal of Medicine 327:742–747, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Bodenheimer T: The not-so-sad history of Medicare cost containment as told in one chart. Health Affairs (suppl Web exclusives):W88-W90, 2002Google Scholar

34. Mechanic D, Schlesinger M, McAlpine DD: Management of mental health and substance abuse services: state of the art and early results. Milbank Quarterly 73:19–55, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. McFarland BH, Winthrop K, Cutler DL: Integrating mental health into the Oregon Health Plan. Psychiatric Services 48:191–193, 1997Link, Google Scholar

36. Barron N, McFarland B, McCamant L: Varieties of centralized intake: the Portland Target Cities Project experience. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 34:75–86, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Gabriel RM, Brown KJ, Deck DD: Six-Month Outcomes of Chemical Dependency Treatment for Medicaid Managed Care Adult Clients: A Study of the Oregon Health Plan. Portland, Oreg, RMC Research Corporation, 2000Google Scholar

38. Carlson M, Gabriel R: Patient satisfaction, use of services, and one-year outcomes in publicly funded substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services 52:1230–1236, 2001Link, Google Scholar

39. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody G, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse clients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. McLellan AT, Cacciola J, Kusher H, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199–213, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Managed Care and Publicly-Funded Chemical Dependency Treatment, 1995–2000: A Review of State, County, and Local Stakeholders' Experiences and Perceptions. Portland, Oreg, RMC Research Coorporation, April 2000Google Scholar

42. Impact of Medicaid Managed Care on Substance Abuse Treatment: Maturation of the Oregon Health Plan. Portland, Oreg, RMC Research Corp, January 2001Google Scholar