Relationship Between Drug Treatment Services, Retention, and Outcomes

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This longitudinal study conducted path analyses to examine the relationships between treatment processes and outcomes among patients in community-based drug treatment programs. METHODS: A total of 1,939 patients from 36 outpatient drug-free and residential treatment programs in 13 California counties were assessed at intake, discharge, three months after admission, and nine months after admission. Path analyses were conducted to relate the quantity and quality of services that were received in the first three months of treatment to treatment retention and outcomes at the nine-month follow-up. Patients were determined to have a favorable outcome if for at least 30 days before the follow-up assessment they did not use drugs, were not involved in criminal activity, and lived in the community. The path analyses controlled for patients' baseline characteristics. RESULTS: Greater service intensity and satisfaction were positively related to either treatment completion or longer treatment retention, which in turn was related to favorable treatment outcomes. Patients with greater problem severity received more services and were more likely to be satisfied with treatment. These patterns were similar for patients regardless of whether they were treated in outpatient drug-free programs or residential programs. CONCLUSIONS: The positive association between process measures—that is, greater levels of service intensity, satisfaction, and either treatment completion or retention—and treatment outcome strongly suggests that improvements in these key elements of the treatment process will improve treatment outcomes.

Drug treatment programs in community settings usually provide a variety of services and strategies for patients with diverse needs. Identifying key effective treatment strategies that these programs have in common has been challenging. Several recent efforts have begun to identify the common aspects of these programs that are directly or indirectly related to outcomes. Some studies have demonstrated that the amount of services received by patients exerts a considerable impact on patient outcomes (1,2,3,4,5,6). For example, McLellan and colleagues (1) demonstrated that patients who received a broader array and increased frequency of services stayed in treatment longer and showed 15 percent better outcomes than patients who did not.

Because longer duration of treatment has been the most consistent and important predictor of favorable treatment outcome (7,8,9,10,11,12,13), Simpson (14) conducted a series of studies that showed that greater program participation was associated with better therapeutic relationships and that both of these factors promoted positive changes in treatment, which are related to longer retention.

Patients' satisfaction with treatment has also been a predictor of favorable treatment outcome and is routinely used by health and human service agencies as an aspect of program accountability (15). The challenges that are associated with measuring the quality of health care are noteworthy. Even though clinicians and patients want care that is safe and effective and there has been growth in the field of quality measurement (16), the divergent needs of disparate stakeholder groups with conflicting agendas have produced heterogeneity among quality indicators, which limits the comparability of results (17,18). In addition, quality measurement may yield results that programs either do not find useful for improving care (19) or lack the infrastructure to implement (20). Nevertheless, with some exceptions (6), several studies have found that patients who are engaged in and satisfied with their treatment experience tend to stay in treatment longer or have better treatment outcomes (15,21,22,23,24).

The existing body of literature documents encouraging progress in understanding which treatment process factors influence treatment outcomes. Questions remain as to whether similar patterns apply to different samples and settings. Our study took advantage of the comprehensive data that were collected in the California Treatment Outcome Project (CalTOP) to address the key research question of how services and satisfaction are related to retention and treatment outcomes. We hypothesized that greater quantity and quality of services would increase the length of treatment stay, which in turn would be positively related to favorable treatment outcomes at nine-month follow-up. These longitudinal relationships were simultaneously tested in a path model by using empirical data from CalTOP.

Methods

Study design

CalTOP was a multisite, multicounty prospective treatment outcome study (25). CalTOP was implemented in April 2000 and collected data at intake, discharge, three months after intake, and nine months after intake for all adult patients in 13 counties who were admitted to 43 programs. The programs consisted of outpatient drug-free programs, residential programs, and methadone maintenance programs. Of the patients followed, 90 percent (N=2,850) completed the three-month follow-up interview and 78 percent (N=2,730) completed the nine-month interview.

Because our analysis focused on treatment process, we included only the patients who had complete data; in addition, only those who were treated in outpatient drug-free programs or residential programs were included. Thus the total sample comprised 1,939 patients. Excluded from the 2,730 patients with nine-month interview data were patients receiving methadone maintenance (119 patients, or 4 percent) and those who did not have all of their intake interview data (91 patients, or 3 percent) or three-month interview data (581 patients, or 21 percent). Comparisons between the 1,939 patients who had complete data and the 1,597 patients who were excluded from the analysis showed that the two groups were similar in age, educational status, marital status, employment, living status, primary drug use, drug treatment history, and legal status at admission—that is, less than a 5 percent difference on each variable. One exception was that women were significantly more likely than men to have completed the follow-up interviews (51.2 percent of women, compared with 42.7 percent of men; χ2=24.8, df=1, p<.001).

Treatment programs

Questionnaires that were completed by the 43 program directors provided the description of treatment characteristics of the participating CalTOP facilities. The typical treatment facility had been in operation for more than 15 years, was part of a larger organization, and had an average daily census of 112 patients (median of 50). All the programs were primarily drug treatment programs, as opposed to alcohol-only treatment programs, and most had a mixture of funding from public and private sources. Most programs offered intake assessment as well as individual and group alcohol and drug counseling.

Intake and follow-up

Patients were assessed at intake, discharge, three months after intake, and nine months after intake. Treatment staff at participating programs completed an in-person assessment as part of the normal admission process and obtained informed consent from participants. Follow-up interviews were conducted over the phone by trained interviewers from the University of California, Los Angeles. Each interview lasted approximately 30 minutes. Patients were paid $10 for the three-month interview and $15 for the nine-month interview.

Instruments and measures

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) was administered at intake and at the nine-month follow-up (26,27). The index is a structured interview that assesses problem severity in seven areas: alcohol use, drug use, employment, family and social relationships, legal status, psychological status, and medical status.

The Treatment Services Review (TSR) was completed with clients during the three-month follow-up interview (4). The measure was used to collect information about the services that were provided to patients during treatment, including the number of professional services and discussion or counseling sessions that the patient received during the first three months of treatment in each of the seven problem areas that were measured in the ASI. We expanded the TSR to include information about services for parenting and child care, HIV support, abuse, case management, and survival support.

A problem severity index (PSI) was determined for patients at intake. The index measured variables that represent the functional domains that are commonly related to treatment goals and outcomes. The PSI is the sum of the presence of seven problems: using multiple drugs (three or more), having an alcohol disorder (alcohol was the primary drug of abuse and was used daily in the past 30 days), having a mental disorder (presence of any serious depression, serious thought of suicide, attempted suicide, or prescribed medication for emotional problems in the past 30 days), being involved with criminal activity (currently on probation or parole, awaiting trial or case pending, or having been arrested or incarcerated in the past 30 days), having low social support for abstinence (living with someone who has current alcohol or drug problems), being unemployed, and receiving public assistance. All problem indicators were dichotomous variables. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 7.

Treatment service intensity is the sum of the number of times that a patient received services (either in the program or through referrals) in the first three months of treatment for each of the 12 types of services that were measured by the TSR. Because the value of this measure was highly skewed, we used its log transformation in the path model.

Treatment satisfaction was indicated by three measures at the three-month follow-up that assessed patients' satisfaction with the program, services, and counseling relationships. Levels of satisfaction were rated by using a Likert scale that ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. Satisfaction with the treatment program was measured by using responses to seven items (Cronbach's alpha=.95); an example item is, "I would recommend this program to a friend." Satisfaction with services was the mean of 12 ratings—one for each of the 12 types of services (alpha=.94). Satisfaction with counseling relationships was determined by analyzing responses to three items (alpha=.88); an example item is, "Your counselor shows a sincere desire to understand." A copy of the instrument can be obtained from the first author. Quality of services referred to the level of treatment satisfaction indicated by these three measures.

Treatment retention was based on data from treatment records that were reported to the state database and was defined as the number of days between CalTOP program admission and discharge. For patients without discharge records, we calculated length of stay as the number of days between admission and the last day of receiving services. Patients were classified as having sufficient retention if they stayed in treatment for 90 days or longer or if they completed treatment. These retention thresholds have been demonstrated to be predictive of positive outcomes (7,8,11).

For an outcome measure we defined the treatment to be a success if at the nine-month follow-up patients reported that for at least 30 days they had not used any illicit drugs, had an ASI drug score of zero, were not involved in criminal activity, and had lived in the community.

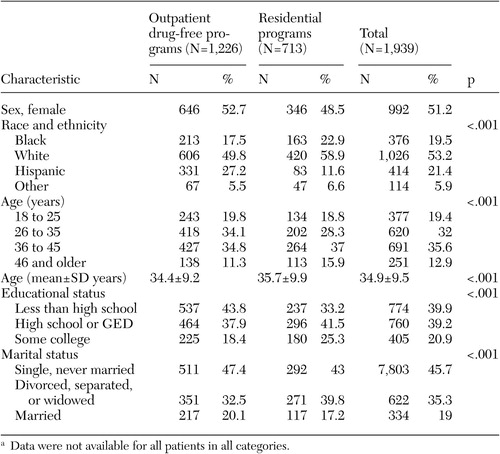

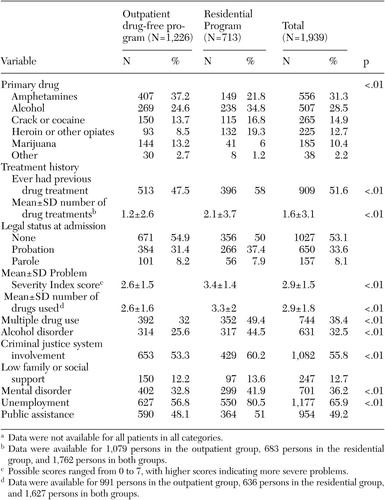

P values were calculated, and they indicate a significant chi square test for percentages by treatment program or a significant t test for the difference of means by treatment program.

Path analyses

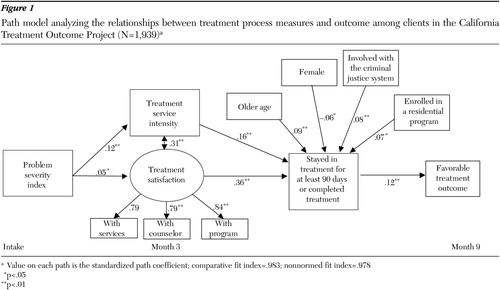

Figure 1 shows the path model representing the hypothesized relationships between treatment process measures and outcome (28,29,30). M-Plus software was used to test the model (31). In the model, the factor in a square represents a single observed measure (for example, problem severity index) and the factor in a circle represents a latent factor (for example, treatment satisfaction) that is indicated by multiple observed measures (for example, satisfaction with services, the counselor, and the program). The arrow indicates the direction of the hypothesized relationship, pointing from an independent variable (for example, problem severity) to a dependent variable (for example, service intensity). A double arrow indicates a bidirectional relationship or a mutual influence between two factors (for example, service intensity and satisfaction). Certain variables (for example, retention) were hypothesized to be both a dependent variable and an independent variable. In addition, age, gender, criminal justice status, and type of treatment program were included as covariates to minimize possible confounding effects.

A standardized path coefficient was estimated for each path in the model to indicate the relationship between two variables; the higher the coefficient, the larger the association. Z tests on parameter estimates and a model modification index were used to identify significant paths, using p<.05 as the criterion. The goodness of fit of the model was evaluated by the model-fitting indexes, including the comparative fit index and the non-normed fit index. The higher the index value, the better the model fit, and a model with an index value of .95 or higher is considered to have a good fit. We also tested the model for different subgroups—outpatient drug-free programs, residential programs, and programs of different planned durations. In addition, we tested the model for a sample that excluded patients who were still in treatment at the nine-month interview (171 patients, or 8.8 percent). Because the results of key relationships were similar for these different groups, we report the results for the full sample, indicating where differences are significant.

Results

Participants

Of the 1,939 patients in the analysis sample, 1,226 were in 24 outpatient drug-free programs and 713 were in 12 residential programs. In the overall study sample, 51.2 percent of patients were female, 53.2 percent were white, 19.5 percent were black, 21.4 percent were Hispanic, and 5.9 percent were from other ethnic groups. The mean±SD age was 34.9±9.5 years. Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the sample by treatment setting.

Pretreatment characteristics

As Table 2 shows, 38 percent of patients were multiple drug users, 33 percent were problem alcohol users, 56 percent were involved in criminal activity, 66 percent were unemployed, and 49 percent were receiving public assistance.

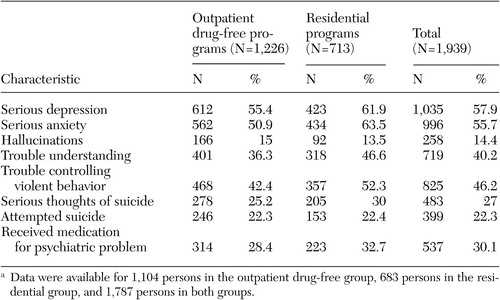

At the intake interview 36 percent of the patients reported severe mental health problems during the past 30 days. Lifetime experiences of psychiatric symptoms are presented in Table 3. More than half of the patients experienced serious depression or anxiety, and slightly less than half reported trouble either understanding or controlling violent behaviors. These high levels of problems suggest the need for mental health services among these patients.

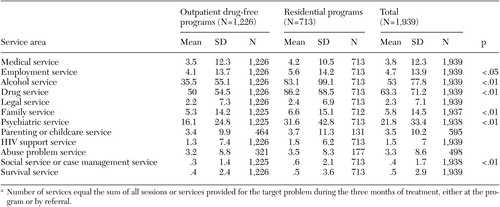

Treatment services received

Table 4 presents the mean TSR service composite scores. (Detailed results about the percentages of individuals who received each specific service can be obtained from the first author.) In general, at least 70 percent of patients received at least one service that focused on alcohol, drugs, or psychiatric problems, and less than half of the patients received services that addressed problems in other areas.

Satisfaction

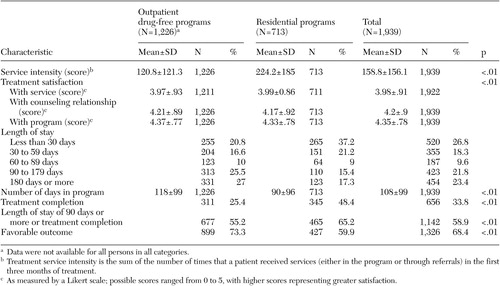

Table 5 shows that satisfaction ratings were high for the program, the service, and the counseling relationships.

Length of stay and outcome

The mean lengths of stay are presented in Table 5. Sixty percent of patients in both types of programs, 65 percent of patients in residential programs, and 55 percent of patients in outpatient drug-free programs had either stayed in treatment for at least 90 days or completed programs that had a planned treatment duration of less than 90 days. Finally, the rate of treatment success was 68 percent overall: 60 percent for patients who were in residential programs and 73 percent for patients who were in outpatient drug-free programs.

Path modeling

As shown in Figure 1, the modeling results confirmed our hypothesis that greater treatment service intensity and treatment satisfaction each independently and significantly contributed to either longer treatment retention or completion of treatment, which in turn was significantly related to treatment success at the nine-month follow-up. Problem severity at intake was positively related to both treatment service intensity and treatment satisfaction; the last two were highly correlated with each other. Being older, being male, being involved with the criminal justice system, and being enrolled in a residential program were all significantly related to either longer treatment stay or completion of treatment. Similar results were found when we tested a separate path model for the sample that excluded patients who were still in treatment at the nine-month follow-up.

Separate path models were tested and compared for patients who were in outpatient drug-free and residential programs, and only two parameters were found to be significantly different. The relationship between treatment satisfaction and treatment retention was significantly stronger for patients in residential programs (standardized path coefficient=.47, p<.01) than for patients in outpatient drug-free programs (standardized path coefficient=.29, p<.01). Also, involvement with the criminal justice system had a significant effect on retention for patients who were in outpatient drug-free programs (standardized path coefficient=.14, p<.01), but it had no impact for patients who were in residential programs.

To investigate the influence of treatment program duration, we conducted separate path analyses for patients who were in programs with short treatment duration (less than 90 days) and patients who were in programs with long treatment duration (90 days or more); results were similar to those presented for the full sample. Only two minor variations were found between these path analyses and the path analysis for the full sample. In the model for the short program duration, patients in residential programs had lower treatment retention than patients in the outpatient drug-free treatment program. In the model for the long program duration, gender and type of treatment were not related to treatment retention or completion.

Discussion

The study results supported our hypothesis that greater quantity and quality of services would increase length of treatment stay, which in turn would be positively related to favorable outcomes at the nine-month follow-up. A reciprocal relationship was seen between service intensity and patient satisfaction. Patients with greater pretreatment problem severity were provided more services, and they were generally more satisfied with the treatment program, the services, and their relationship with counselors. Also of interest was the finding that being older, being male, and being involved with the criminal justice system were positively associated with either treatment completion or longer treatment retention. Although patients in residential programs had more severe problems than patients in outpatient drug-free programs, the path analyses found few differences between these two types of programs.

Findings of our analysis were relatively straightforward, as were their implications. Retention is primarily an index that captures the impact of several interrelated patient and treatment process measures (32). Effective intervention strategies should be identified or developed to improve one or more of these key elements of treatment process that are fundamental to treatment effectiveness. The complexity and severity of the associated medical, employment, family, and legal problems of substance-abusing patients were significant impediments to sustained reductions in substance use. Focused interventions that target both substance use and other related needs are necessary for effective rehabilitation (6). Additionally, patient satisfaction is integral to the measurement of the quality of behavioral health services, and our study demonstrated the positive impact of patient satisfaction on treatment retention. Also, the reciprocal relationship between service intensity and patient satisfaction suggests that increasing service intensity will increase patient satisfaction. Thus procedures and standards for programs to document patient engagement and progress are needed to establish program accountability and competence (33,34). This information will be valuable for making policy decisions about treatment services and settings for agencies.

Before concluding, we acknowledge several study limitations. The counties and treatment programs that participated in CalTOP were not randomly selected. It is therefore possible that the observed patterns cannot be generalized to other programs that do not provide similar services to their patients. The analysis sample excluded patients who were treated in methadone maintenance programs, who died during the study period, who were incarcerated, and with whom contact was lost during the follow-up period—patients in these groups represented about half of the patients who were admitted to CalTOP during the recruitment period. Attrition analysis showed that patients with complete data and patients without complete data had similar characteristics, except for the fact that women were overrepresented in the study sample. In addition, a majority of data were derived from patient self-report. A major consideration in all studies that use self-report data is the reliability and validity of the information collected. However, the instruments and procedures that were employed in this study are those that are most widely used in the substance abuse treatment field and that have been validated in similar studies with this population (1,5,35,36). Finally, even though path analysis is a useful tool for testing complex relationships among multiple factors, data from a nonexperimental study cannot firmly establish causal relations.

Conclusions

Our study provided empirical support for the theory that several key treatment process components are related to treatment retention and outcomes. Greater service intensity and quality were both related to either treatment completion or longer treatment retention, which in turn was related to better follow-up outcomes. These study findings contribute to a growing body of evidence that supports the concept that improved quality of care during treatment can improve treatment outcomes. The paradigm shift from emphasizing the role of patient characteristics to recognizing the potential influence of the quality of the program and the services has yielded important information that can contribute to the identification of best practices and evidence-based principles for care. Future efforts should encourage or facilitate implementation of changes in program design and service delivery according to best practices in order to improve the quality of treatment and patients' outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant 1-UR1-TI11478-01 from the California Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs under the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment TOPPS II (Treatment Outcomes and Performance Pilot Studies Enhancement) and by grant R01-DA-15431 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Hser and Dr. Anglin were also supported by Independent Scientist Awards K02-DA-00139 and K05-DA-00466, respectively.

The authors are affiliated with the Neuropsychiatric Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, 1640 South Sepulveda Boulevard, Suite 200, Los Angeles, California 90025 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Path model analyzing the relationships between treatment process measures and outcome among clients in the California Treatment Outcome Project (N=1,939)a

a Value on each path is the standardized path coefficient; comparative fit index=.983; nonnormed fit index=.978

|

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients in the California Treatment Outcome Project, by treatment program typea

a Data were not available for all patients in all categories.

|

Table 2. Baseline history of substance use, criminal justice system involvement, and previous treatment of patients in the California Treatment Outcome Project, by treatment program typea

a Data were not available for all patients in all categories.

|

Table 3. Psychiatric symptoms that were experienced by patients in the California Treatment Outcome Project over their lifetime, by treatment program typea

a Data were available for 1,104 persons in the outpatient drug-free group, 683 persons in the residential group, and 1,787 persons in both groups.

|

Table 4. Services provided to patients in the California Treatment Outcome Project during the first three months of treatment, bytreatment program typea

a Number of services equal the sum of all sessions or services provided for the target problem during the three months of treatment, either at the program or by referral.

|

Table 5. Service intensity in the first three months of treatment, satisfaction in the first three months of treatment, and nine-month outcomes among patients in the California Treatment Outcome Project, by treatment program type

1. McLellan AT, Woody GE, Metzger D: Evaluating the effectiveness of addiction treatments: reasonable expectations, appropriate comparisons. Milbank Quarterly 74:51–85, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hoffman JA, Caudill BD, Koman JJ, et al: Psychosocial treatments for cocaine abuse:12–month treatment outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 13:3–11, 1996Google Scholar

3. Hser YI, Polinsky ML, Maglione M, et al: Matching patients' needs with drug treatment services. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 16:299–305, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

4. McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Cacciola J, et al: A new measure of substance abuse treatment: initial studies of the treatment services review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:101–110, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. McLellan AT, Grissom GR, Brill P, et al: Private substance abuse treatments: are some programs more effective than others? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 10:243–254, 1993Google Scholar

6. McLellan AT, Hagan TA, Levine M, et al: Supplemental social services improve outcomes in public addiction treatment. Addiction 93:1489–1499, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Simpson DD, Joe G, Fletcher B, et al: A national evaluation of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:507–514, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. De Leon G: Retention in drug-free therapeutic communities, in Improving Drug Abuse Treatment. NIDA Research Monograph 106. Edited by Pickens RW, Leukefeld CG, Schuster CR. Department of Health and Human Services pub no ADM-91–1754. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1991Google Scholar

9. Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, et al: Drug Abuse Treatment: A National Study of Effectiveness. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 1989Google Scholar

10. Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Flynn PM, et al: Overview of 1-year follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS). Psychology of Addict Behaviors 11:261–278, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Simpson DD: The relation of time spent in drug abuse treatment to posttreatment outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:1449–1453, 1979Link, Google Scholar

12. Simpson DD: Treatment for drug abuse: follow-up outcomes and length of time spent. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:875–880, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal GA: Drug abuse treatment retention and process effects on follow-up outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 47:227–235, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Simpson DD: Modeling treatment process and outcomes. Addiction 96:207–211, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Sanders LM, Trinh C, Sherman BR, et al: Assessment of client satisfaction in a peer counseling substance abuse treatment program for pregnant and postpartum women. Evaluation and Program Planning 21:287–296, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Wolpert M: Quality indicators: defining and measuring quality in psychiatric care for adults and children: report of the APA task force on quality indicators and report of the APA task force on quality indicators for children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 44:929, 2003Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Hermann RC, Palmer RH: Common ground: a framework for selecting core quality measures for mental health and substance abuse care. Psychiatric Services 53:281–287, 2002Link, Google Scholar

18. Hermann RC, Rollins CK: Quality measurement in health care: a need for leadership amid a new federalism. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 11:215–219, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Valenstein M, Mitchinson A, Ronis DL, et al: Quality indicators and monitoring of mental health services: what do frontline providers think? American Journal of Psychiatry 161:146–153, 2004Google Scholar

20. McLellan AT, Carise D, Kleber HD: Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public's demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 25:117–121, 2003Google Scholar

21. Kasprow WJ, Frisman L, Rosenheck RA: Homeless veterans' satisfaction with residential treatment. Psychiatric Services 50:540–545, 1999Link, Google Scholar

22. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB: Outcomes of inpatients treated on a VA psychiatric unit and a substance abuse treatment unit. Psychiatric Services 48:699–704, 1997Link, Google Scholar

23. Evans E, Hser, YI: Patients' needs, services, and treatment satisfaction. Poster presented at the 62nd Annual Scientific Meeting, College on Problems of Drug Dependence, San Juan, Puerto Rico, June 17–22, 2000Google Scholar

24. Carlson MJ, Gabriel RM: Patient satisfaction, use of services, and one-year outcomes in publicly funded substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services 52:1230–1236, 2001Link, Google Scholar

25. Hser YI, Evans, L, Teruya, C, et al: The California Treatment Outcome Project (CalTOP): Final Report. Los Angeles, University of California, Integrated Substance Abuse Programs, California Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs, 2002Google Scholar

26. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199–213, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Hoyle RH: Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Application. Thousand Oaks, Sage, 1995Google Scholar

29. Klem L: Path analysis, in Reading and Understanding Multivariate Statistics. Edited by Grimm, LG, Yarnold, PR. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1998Google Scholar

30. Loehlin JC: Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Analysis. London, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992Google Scholar

31. Muthen LK, Muthen BO: M-Plus User's Guide: The Comprehensive Modeling Program for Applied Researchers. Los Angeles, Muthen and Muthen, 1999Google Scholar

32. Simpson DD, Joe GW, Rowan-Szal GA, et al: Drug abuse treatment process components that improve retention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 14:565–572, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Simpson DD, Joe GW, Dansereau DF, et al: Strategies for improving methadone treatment process and outcomes. Journal of Drug Issues 27:239–260, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Moos R, Finney JW, Federman B, et al: Specialty mental health care improves patients' outcomes: findings from a nationwide program to monitor the quality of care for patients with substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 61:704–713, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. McLellan AT, Grissom GR, Zanis D, et al: Problem-service "matching" in addiction treatment: a prospective study in 4 programs. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:730–735, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Alterman AI, O'Brien CP, McLellan AT, et al: Effectiveness and costs of inpatient versus day hospital cocaine rehabilitation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:157–163, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar