An Examination of Leading Mental Health Journals for Evidence to Inform Evidence-Based Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined whether data needed to inform evidence-based practice can be found in leading mental health journals. METHODS: Research studies described in articles that were published in 12 leading mental health journals in 1999 were examined to determine whether they evaluated clinical interventions, used rigorous designs, were conducted in routine practice settings, and included well-defined diagnostic groups and heterogeneous samples. RESULTS: Twenty-seven percent (N=295) of the 1,076 articles that were reviewed described research that evaluated interventions. Of these 295 articles, 64 percent evaluated pharmacologic interventions and 33 percent evaluated psychosocial or psychotherapeutic interventions. Of the articles that evaluated interventions, 60 percent described randomized designs, but samples were modest; 25 percent of the studies reported 31 or fewer participants. Of the 295 articles, 84 percent described studies conducted in specialty mental health settings; very few (4 percent) described studies conducted in public mental health or managed care environments, which are common practice settings. Most samples were diagnostically well defined, but evidence of treatments for diagnoses other than schizophrenia and mood disorders was limited. CONCLUSIONS: This systematic review suggested that data needed to inform and advance evidence-based practice does not have the prominent place it deserves in leading journals. Only a quarter of the research studies that were examined evaluated clinical interventions, and articles that described pharmacologic interventions were published twice as often as articles that described psychosocial or psychotherapeutic interventions. Rigorous research designs predominated, but sample sizes were modest. Evidence was scarce on treatment effectiveness in routine practice settings.

Many authors have recently noted that evidenced-based mental health interventions are rarely implemented in routine practice settings (1,2,3). Rigorous criteria for evidence-based practices have been specified, and significant efforts have been made to encourage the adoption of these interventions in routine care settings. Nonetheless, adoption of these practices has been disappointingly slow, keeping individuals from receiving optimal care for their mental health problems and preventing mental health systems from operating at optimal efficiency (4,5). The body of published evidence may not yet be sufficient to persuade clinicians and policy makers to adopt evidence-based practices.

Scholarly publication of research evidence is only the first of many steps in disseminating evidence-based practices, but it is an important initial step (6,7). Evidence will not reach practitioners and policy makers through accessible outlets such as review articles and practice-focused journals without the approval and sanction signaled by publication in leading research journals. It is essential that readers find evidence that is rigorous and relevant to practice in the leading journals that are respected as prime sources of high-quality research. Thus it is worth considering whether the evidence that practitioners and policy makers need to implement evidence-based interventions in routine practice settings can be found in leading journals.

Established measures of journal prestige and quality facilitate the identification of leading research journals. The most widely used indicator is the journal impact factor, or JIF, which is computed by the Institute for Scientific Information for journals that are included in the Science Citation Index and the Social Science Citation Index (8). Although the journal impact factor is the subject of some controversy (9,10), evidence generally validates it as an indicator of journal quality and a measure of the journal's influence on researchers, practitioners, and other readers (11,12,13,14,15).

The growing body of literature on evidence-based medical care provides objective standards for evaluating the scientific rigor of research and the resulting quality of evidence for the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions. Various hierarchical systems exist for evaluating the quality of evidence (16,17). In both efficacy and effectiveness research, large, well-controlled randomized trials provide the highest-quality evidence, followed by smaller randomized trials, nonrandomized group comparisons, systematic observational studies, and unsystematic observational studies. Overall, research designs that minimize bias and maximize generalizability yield the highest-quality evidence. Effectiveness studies also emphasize relevance to routine practice settings. Evidence from studies that reflect the characteristics of practice settings, such as public-sector and managed care settings, will be more persuasive than studies from purely academic research settings. Evidence of treatment effectiveness in diverse client populations—reflecting heterogeneity in age, gender, culture, social class, psychiatric diagnosis, and health status—increases both the relevance and the generalizability of published evidence.

Our study examined an existing data set that was created for study on mental health outcome measurement to evaluate whether the data needed for evidence-based practice can be found in leading mental health journals that publish treatment outcome research. The data set contained information on journal articles that were published in 1999. The data set was examined to determine whether the articles described studies that evaluated clinical interventions, used rigorous research designs, were conducted in routine practice settings, and included well-defined diagnostic groups and heterogeneous patient samples.

Methods

Journal identification and selection

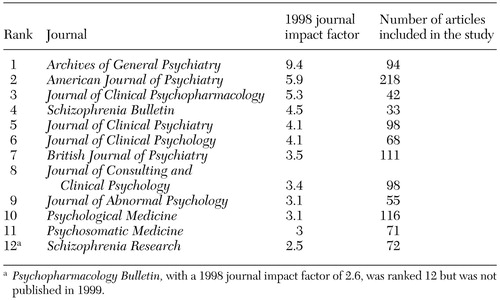

Leading mental health journals were initially identified by using the journal impact factor that was found in the 1998 Journal Citation Reports (18). Psychiatry journals were identified in the Science Edition, and clinical psychology journals were identified in the Social Science Edition. The journal impact factor is calculated as the average number of times articles published in a journal during the previous two years were cited in a particular year. The psychiatry and clinical psychology lists were combined, duplicates were eliminated, and the remaining journals were sorted by impact factor. The contents of the 30 journals with the highest impact factors were then reviewed. Because the original study's focus was on outcome measurement among adults, journals were eliminated from consideration if they did not publish treatment outcome research or focus primarily on adults. Journals were then selected from the remaining list in descending order of journal impact factor until a sample of approximately 1,000 articles on studies that used outcome measures was achieved. The 12 selected journals and their journal impact factors are listed in Table 1.

Article identification and selection

A complete list of articles that were published during 1999 in the selected journals was extracted from the MEDLINE-Health STAR database. Categories of articles that were not expected to involve outcome measurement—such as book reviews, letters, or obituaries—were excluded at this stage, yielding a sample of 1,637 articles. The full text of each article was then reviewed. Articles were excluded from further consideration if they did not use outcome measures; used only laboratory tests or other biologic data, such as blood assays or imaging procedures; or used only standard psychological tests, such as intelligence or projective tests. Review articles, book reviews, editorials, letters, or obituaries that had not been identified during the initial database search were also excluded at this stage. The final sample comprised 1,076 articles.

Article and measure evaluation

Information on each article was recorded on a standardized data collection form, which characterized the study and each outcome measure used. Each study was characterized in terms of its sample, clinical context, and research design. Sample characteristics included the ages of the participants, the diagnostic composition of the sample, and the sample size. The clinical context was described in terms of whether clinical interventions were evaluated, the nature of the interventions, and the clinical setting. Research designs were classified as randomized trials, nonrandomized group comparisons, single group studies, or other types of design.

Results

Twenty-seven percent (N=295) of the 1,076 articles that were evaluated presented evidence of one or more clinical interventions. All studies that evaluated interventions were included, encompassing efficacy and effectiveness studies as well as feasibility studies and other observational studies. Of these 295 articles, 64 percent (N=190) evaluated pharmacologic interventions, 33 percent (N=98) evaluated psychotherapy or psychosocial interventions, and 12 percent (N=36) evaluated other types of interventions, such as magnetic stimulation or light therapy. (Totals may exceed 100 percent because some studies evaluated more than one intervention.)

The most common research design that was employed in the 295 intervention studies was the randomized controlled trial, which was used in 59 percent of the studies (N=175). Single group studies (24 percent, or 71 studies) were the next most common design, followed by nonrandomized group studies (11 percent, or 32 studies), and other designs (6 percent, or 17 studies). Sample sizes ranged from one, for a single case report, to 25,996, for a randomized trial of a brief behavioral smoking cessation intervention. The mean sample size was 313, and the median sample size was 80. Twenty-five percent of the articles that reported intervention studies (N=74) described studies in which 31 or fewer persons participated.

A majority of the 295 articles (83 percent, or 246 articles) described interventions that were conducted in a specialty mental health or substance abuse facility, 7 percent (N=20) took place at another kind of medical facility, and 10 percent (N=29) took place in a nonmedical setting, including school and home settings. Only 4 percent of articles specifically noted that the sample selection or interventions took place in prevalent systems of care, such as a managed care environment (1 percent, or four articles) or a public mental health system (3 percent, or eight articles).

Seventy-nine percent (N=233) of the articles on intervention studies described participants who were selected on the basis of psychiatric diagnoses. The most frequently studied diagnostic category was mood disorders, followed by schizophrenia. Of articles that focused on specific diagnostic groups, 39 percent (N=92) focused on mood disorders, 26 percent (N=60) on schizophrenia, 10 percent (N=23) on anxiety disorders, 5 percent (N=12) on substance use disorders, and 1 percent (N=3) on personality disorders. Twenty-two percent of these articles (N=52) focused on "other" diagnostic groups. The most common of these diagnoses were obsessive-compulsive disorder (3 percent, or eight articles), attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (3 percent, or seven articles), and posttraumatic stress disorder (2 percent, or five articles).

Adults were primarily studied in these intervention trials (86 percent, or 255 articles). Twelve percent (N=36) of studies included persons who were elderly, 5 percent (N=15) included adolescents, and 6 percent (N=18) included children. In 68 percent of articles (N=200) the intervention studies were conducted in the United States, whereas 32 percent (N=95) of the articles reported studies conducted in other countries, most commonly the United Kingdom, Canada, and Germany.

Discussion

Systematic review of articles that were published in leading mental health journals suggests that the evidence required to inform and advance evidence-based practices may be inadequately represented in the most prestigious and influential journals. As discussed in more detail below, published articles do not provide sufficient generalizable data on the range of interventions or settings that are needed to inform the implementation of evidence-based practices in routine care. Clinicians and decision makers who turn to these journals for data to inform practice are likely to be disappointed.

A surprisingly modest number of studies provided evidence that was related to interventions. Even when the full range of intervention studies was included, only 27 percent of the articles published in the 12 leading journals presented evidence about clinical interventions, ranging from single case designs to rigorous randomized trials. This lack of data from intervention studies clearly limits the availability of evidence of treatment efficacy or effectiveness that is validated by the editors and reviewers of the most respected mental health journals. Although epidemiologic, psychobiologic, and nosologic studies are essential to the advancement of mental health care, intervention studies have the most direct and immediate application in practice settings. Evidence was also quite skewed toward pharmacologic interventions. Two-thirds of the articles we examined evaluated pharmacologic interventions, whereas only one-third evaluated psychosocial or psychotherapeutic interventions. This modest body of data cannot provide definitive evidence about the wide range of relevant psychosocial or psychotherapeutic treatments.

It is encouraging in terms of scientific rigor and study quality that a majority of intervention studies (60 percent) employed randomized designs. This type of study is likely to yield the highest-quality evidence. However, it is troubling that single group designs (24 percent) were twice as common as nonrandomized group comparisons (11 percent). Nonrandomized group comparisons yield higher-quality evidence than single group designs and are particularly well suited to effectiveness research that is conducted in real-world treatment contexts, which provides results that are generalizable to various treatment settings and systems. The average study sample of 313 participants seems to have sufficient power to test hypotheses of moderate complexity. However, the median sample size was only 80, and a quarter of the intervention studies that we found involved 31 or fewer participants. Because these figures reflect total study sample sizes and not the size of comparison groups within studies, many of the studies may have lacked the power to detect meaningful differences.

Evidence of the effectiveness of interventions in typical practice settings was particularly scarce. Only 4 percent of intervention studies were identified as being conducted in public mental health settings or managed care settings, two very common practice settings. Most intervention studies appeared to have been conducted in specialized academic research settings, although many articles did not clearly describe the study setting. Even though participants in some of the studies seemed to have been recruited from public-sector, managed care, and other practice settings, results of studies that were conducted in specialized research settings may not generalize directly to routine care settings.

A majority of studies that were described in the 12 leading journals were diagnostically well defined. The most commonly studied disorders pose significant burden to affected individuals and to society, specifically schizophrenia—which is relatively rare but highly disabling—and mood disorders—which are highly prevalent. However, evidence was limited for disorders that are somewhat less common, but still prevalent, such as substance use, anxiety, and personality disorders.

Our study has a number of limitations resulting from the use of data that were originally collected for a study of outcome measurement. These limitations, related to selection of journals, articles, and individual variables, could affect the interpretation of our results. The journals included were all published in a single year, and several years have passed since their publication. Journals were originally selected for a study of mental health outcome measurement in adults which led to the exclusion of journals that did not publish outcome data or did not focus primarily on adults. Also, the use of the journal impact factor in the selection process biases the sample toward English-language journals and studies conducted in English-speaking countries. Articles were also selected to match the original focus on outcome measurement, and studies that did not use at least one outcome measure were excluded.

The set of study characteristics measured was also quite limited and did not include important indicators of sample representativeness, such as gender, race, and ethnicity. Similarly, samples that were not selected on the basis of diagnoses were not classified, making it impossible to distinguish between psychiatric samples and nonpsychiatric convenience or analog samples, such as college students. Finally, the categorization of both interventions and treatment settings in our data was lacking in detail.

These limitations may affect the magnitude and precision of the findings, but they are unlikely to affect our study's core conclusions. It is difficult to imagine that focusing on a single year would bias the results. Journals do run special issues and change their editorial policies; however, it is unlikely that 1999 was an anomalous year for all 12 of the journals that were included in our study. Since 1999, it is likely that the increased attention to evidence-based practices has shifted publication trends toward the publication of more evidence that can inform evidence-based practice. However, given the lag time to publication, it is not likely that such shifts would dramatically alter the main conclusions of our study. For example, even if the number of studies conducted in public mental health settings doubled, these studies would represent only 6 percent of studies reported. Clearly, a much larger body of evidence is required, and these data from 1999 can serve as a reference point for future examinations of publication trends.

Excluding journals that did not focus primarily on adults clearly reduced the representation of studies involving children, adolescents, and the elderly. Given the original study's focus on outcome measurement, journals focusing primarily on these age groups were excluded because they pose special measurement considerations that merit separate attention. However, there is no reason to think that studies focusing on these age groups would involve significantly different types of interventions, settings, and research designs than studies focusing primarily on nonelderly adults. Excluding journals and articles that did not match the original focus on outcome measurement resulted in a restricted sample of articles. This selection strategy may have eliminated some articles describing analyses of aggregate data, particularly utilization and cost data, that might provide valuable evidence for treatment systems and practice settings. However, most studies that do not use any form of outcome measurement are preclinical, neurobiological studies that do not have direct application in practice. The relative amount of practice-relevant data would likely decrease if these excluded journals and articles had been included. The limited array of variables characterizing samples, interventions, and settings does limit the scope of our study's conclusions. However, these omissions do not affect the validity or interpretability of the data that were collected.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that data needed for evidence-based practice is not sufficiently available in leading mental health journals. Only a minority of the studies we examined evaluated interventions, and a majority of the intervention studies focused on pharmacologic rather than psychosocial or psychotherapeutic treatments. Although randomized designs were common, sample sizes were relatively modest, which raises questions about statistical power and interpretability. Very few reports existed of studies that were conducted in routine practice settings, such as managed care or public mental health settings. Impact factor scores did not appear to translate directly into impact on clinical practice. Although leading research journals are certainly not the only outlets for research findings, publication of evidence in prestigious journals offers a stamp of approval that furthers the dissemination of information.

Our findings have implications for clinical care, mental health policy, and future research. Clinicians and decision makers are unlikely to find the data that they need to implement evidence-based practices in the leading mental health journals. Evidence of the efficacy of interventions was only modestly represented, and evidence of the effectiveness of interventions in the most common practice settings was quite scarce. The limited number of intervention studies that were published did not provide sufficient evidence of replicability to justify a large-scale implementation. Prestigious journals appeared to favor internal validity and basic neuroscience research—in the form of small, well-controlled laboratory experiments—over external validity and direct applicability—in the form of larger, real-world clinical studies. Although basic neuroscience research is essential to the development of effective treatments, a majority of readers of general mental health journals cannot make direct use of the results of such studies. Lack of relevance is likely to reduce some readers' confidence in the research enterprise and limit enthusiasm for applying evidence-based practices in clinical practice.

Researchers, funders, and journals can work collaboratively to simultaneously maintain high scientific standards and to increase the number of intervention studies and the generalizability of the evidence published in leading journals. Researchers can be more aggressive in pursuing opportunities to conduct research in routine practice settings and be more conscientious in ensuring and documenting the external validity of that research so that it can be published in the most prestigious journals. Characteristics of samples and settings should be described in sufficient detail for readers to assess the generalizability of findings to specific populations and practice contexts. Funders can work to increase the number of rigorous and relevant studies that are conducted, and journals can explicitly expand their definition of scientific quality to include external validity and generalizability. Journals can also require more detailed explanations of samples and settings. These efforts can help to increase the quantity and quality of published evidence to inform evidence-based mental health care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant MH-64073 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Francine Rozewicz, Barbara Blackman, and Wynne Bamberg for their assistance with this study and Charles Hunt and Cheryl Schutz of PERQ/HCI Research for making their archival survey results available.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, 2727 Mariposa Street, Suite 100, San Francisco, California 94110 (e-mail, [email protected]). Preliminary results of this study were presented at the International Conference on Mental Health Services Research of the National Institute of Mental Health, held April 1 to 3, 2002, in Washington, D.C.

|

Table 1. Journals examined for a study that determined whether data needed to inform evidence-based practice was available in leading mental health journals in 1999

1. Geddes J: Evidence based practice in mental health. British Medical Journal 315:1483–1484, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. National Advisory Mental Health Council's Clinical Treatment and Services Research Workgroup. Bridging Science and Service: A Report. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

3. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

4. Drake RE, Goldman RH, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179–182, 2001Link, Google Scholar

5. Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:45–50, 2001Link, Google Scholar

6. Corrigan PW, Steiner L, McCracken SG, et al: Strategies for disseminating evidence-based practices to staff who treat people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:1598–1606, 2001Link, Google Scholar

7. Corrigan P, McCracken S, Blaser B: Disseminating evidence-based mental health practices. Evidence-Based Mental Health 6:4–5, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Garfield E: Which medical journals have the greatest impact? Annals of Internal Medicine 105:313–320, 1986Google Scholar

9. Seglen PO: Why the impact factor of journals should not be used for evaluating research. British Medical Journal 314:498– 502, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bloch S, Walter G: The impact factor: time for a change. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 35:563–568, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lee KP, Schotland M, Bacchetti P, et al: Association of journal quality indicators with methodological quality of clinical research articles. JAMA 287:2805–2808, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Callaham M, Wears RL, Weber E: Journal prestige, publication bias, and other characteristics associated with citation of published studies in peer-reviewed journals. JAMA 287:2847–2850, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Focus Medical/Surgical Publications. Princeton, NJ, PERQ/HCI Corp, 2000Google Scholar

14. Saha S: Impact factor: a valid measure of journal quality? Journal of the Medical Library Association 91:42–46, 2003Google Scholar

15. Tsay MY: The relationship between journal use in a medical library and citation use. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 86:31–39, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

16. Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al: Users' guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the users' guides to patient care. JAMA 284:1290–1296, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Sackett DL, Strauss SE, Richardson WS, et al: Evidence Based Medicine. London, Churchill Livingstone, 2000Google Scholar

18. Journal Citation Reports (JCR). Philadelphia, Institute for Scientific Information, 1999Google Scholar