A Pilot Study of Brief Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depression Among Women

Abstract

A matched-case-control study compared eight-week outcomes between a group of 16 depressed women who received brief (eight-session) interpersonal psychotherapy and a group of 16 who received a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (sertraline). Women who met DSM-IV criteria for major depression and who had a score above 15 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression were treated openly with brief interpersonal psychotherapy and were matched on key variables with women being treated with sertraline. Linear mixed-effects regression models were used to compare groups on measures of symptoms and functioning during eight weeks of treatment. Both groups improved significantly over time, with large effect sizes. However, contrary to expectations, the women who received psychotherapy improved more quickly than those who received sertraline.

Little is known about the optimal duration, or "dosage," of psychotherapy. Many therapists assume that greater durations are better, but virtually no data are available to support this belief (1). The fact that there is a paucity of empirical evidence linking longer durations of therapy to enhanced therapeutic effects raises the possibility that favorable outcomes might be achieved with few sessions.

Conventional wisdom suggests that pharmacotherapy alleviates depressive symptoms more quickly than psychotherapy (2). However, it is possible that patients and therapists work harder and faster when the number of psychotherapy sessions is limited from the outset (3), thereby hastening the onset of psychotherapy's antidepressant effects. Time-limited psychotherapy for depression with an onset of action comparable to that for pharmacotherapy would offer patients rapid relief from their symptoms and would give therapists a means of deploying their resources more efficiently.

Interpersonal psychotherapy is an efficacious 12- to 16-session treatment for depression that explores the link between mood symptoms and interpersonal relationships (4). Although most depressed women experience many interpersonal problems and might benefit from a full course of interpersonal psychotherapy, those in a predominantly low-income community setting were found to be unlikely to attend 16 sessions of psychotherapy (5). We therefore developed and tested an eight-session form of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed women.

The primary aims of the pilot study reported here were to assess the acceptability of brief interpersonal psychotherapy to patients and to estimate treatment effect sizes. We then used a quasi-experimental design to compare women who received brief interpersonal psychotherapy with a matched group of women who received pharmacotherapy (sertraline) and supportive psychotherapy during eight weeks of treatment.

Methods

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the institutional review board of the University of Pittsburgh. The women in the brief interpersonal psychotherapy group were treated openly with eight weekly sessions. The women who were treated with sertraline were part of a study that has been described elsewhere (6) and that was characterized by a four-week placebo lead-in followed by random assignment to receive either sertraline or placebo, administered in combination with supportive psychotherapy. For the purposes of these analyses, we selected 16 sertraline-treated women out of a possible 24. The women selected for participation were those who most closely matched the women who received brief interpersonal psychotherapy in terms of age and baseline score on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HRSD-17) (7).

Eligible participants were women who met criteria for current major depressive disorder on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV and had a score of more than 15 on the HRSD-17 (Possible scores range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating more depression symptoms.) Exclusion criteria included psychosis, a history of mania or hypomania, current substance abuse or dependence, active suicidal ideation, significant medical illness, and current use of antidepressant medications.

Participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (8), and an independent evaluator administered the HRSD-17 and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) at each visit. After session 8, the women in the interpersonal psychotherapy group completed the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ), an eight-item instrument for assessing subjective satisfaction with treatment (9).

Brief interpersonal psychotherapy consists of eight weekly, 45-minute individual sessions. This form of psychotherapy retains the essential features of interpersonal psychotherapy (4) while emphasizing strategies that lead to rapid interpersonal change. Therapists also use behavioral activation strategies (10) and assign interpersonally focused homework. An unpublished treatment manual is available on request from the first author. The therapists were a psychiatrist, a nurse, and a social worker.

The patients who received sertraline were treated with a starting dosage of 50 milligrams a day. Dosages were titrated upwards according to tolerability and clinical status. The mean dosage at week 8 was 134.38±35.21 mg a day. Participants also received supportive counseling at each weekly visit. Individual supportive psychotherapy sessions lasted 45 to 50 minutes and were conducted by master's-level nurse clinicians.

All analyses were performed by using SAS/STAT. To compare the groups over time on measures of symptoms and functioning, linear mixed-effects regression models were computed with unstructured covariance matrixes by using PROC MIXED. Treatment group was used as a fixed effect, and random intercepts and effects of weeks of treatment were allowed for each participant. To compare clinical and demographic characteristics between the two groups, t tests were used for continuous variables and chi square or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables. Estimates of effect size were computed by using Cohen's d statistic on changes in HRSD and GAS scores from baseline to completion of the study or termination.

Results

The groups did not differ significantly on any demographic variable, including age, education, employment, marital status, and ethnicity, nor on baseline clinical features, including number of previous episodes of depression or duration of current episode. In the sertraline group, significantly more time (in weeks) elapsed between screening and initial assessment compared with the brief interpersonal psychotherapy group (4.55±2.22 compared with 1.68±.97; t=−6.13, df=27, p<.001). In the sertraline group, BDI and GAS scores improved significantly from screening to visit 1 (t=4.06, df=15, p=.001; t=−2.32, df=15, p=.04, respectively), but no differences were noted in HRSD-17 scores. In the brief interpersonal psychotherapy group, no significant changes in HRSD-17, BDI, or GAS scores between screening and visit 1 were noted.

Thirteen (76 percent) of the women who received brief interpersonal psychotherapy completed all eight treatment sessions. Two dropped out, and one was withdrawn for clinical worsening. Fifteen (94 percent) of the women who received sertraline completed treatment through week 8, and one dropped out. All but one of the women who completed brief interpersonal psychotherapy reported that eight sessions were sufficient to meet their needs and that they were very satisfied with their treatment; the mean CSQ score posttreatment was 28.5±4.6 (possible scores range from 8 to 32, with higher scores reflecting greater satisfaction).

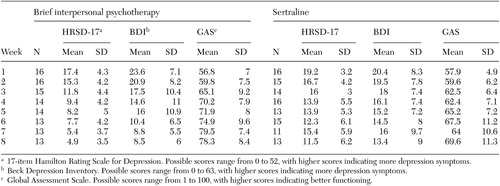

Effect sizes were robust for both groups. The brief interpersonal psychotherapy intervention was associated with somewhat greater effects than the sertraline intervention: an effect size of 1.9 compared with 1.7 for HRSD scores and 1.9 compared with 1.4 for GAS scores. Highly significant time effects indicate that both groups improved on measures of symptoms—HRSD-17 scores (F= 96.40, df=1, 30, p<.001) and BDI scores (F=50.07, df=1,29, p<.001)—and on the measure of functioning—GAS scores (F=67.71, df=1, 30, p<.001) over time. Significant time-by-group interaction effects indicate that the brief interpersonal psychotherapy group improved at a faster rate than the sertraline group on HRSD-17 scores (F=4.76, df=1, 161, p=.03), BDI scores (F=5.24, df=1, 154, p=.02), and GAS scores (F=5.32, df=1, 161, p=.02). Mean±SD symptom and functioning scores over time are listed in Table 1.

Discussion and conclusions

A majority of the women who received brief interpersonal psychotherapy reported that they found this form of treatment acceptable, and treatment effect sizes were large. Contrary to expectations, improvement occurred more rapidly with brief interpersonal psychotherapy than with sertraline. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that expectation plays an important role in amelioration of depressive symptoms (3).

This study had many limitations. The small sample and the quasi-experimental design limit generalizability of results. Although the groups did not differ on most clinical and demographic variables, comparability of the two groups cannot be assured. The placebo lead-in design of the sertraline study raises the possibility that the sertraline group had placebo-resistant depression, and some of the improvement in the interpersonal psychotherapy group may have been due to a placebo effect. Comparative durability of treatment response was not assessed. Nevertheless, results of this pilot study suggest that brief interpersonal psychotherapy is a promising form of treatment for depression among women and one that warrants further investigation.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, 3811 O'Hara Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Weekly scores on symptom and functioning measures among women who received brief interpersonal therapy or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (sertraline)

1. Gunderson JG, Fonagy P, Gabbard GO: The place of psychoanalytic treatments within psychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:505–510, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Watkins JT, Leber WR, Imber SD, et al: Temporal course of change of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61:858–864, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Reynolds S, Stiles WB, Barkham M, et al: Acceleration of changes in session impact during contrasting time-limited psychotherapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:577–586, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL: Comprehensive Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York, Basic Books, 2000Google Scholar

5. Swartz HA, Shear MK, Frank E, et al: A pilot study of community mental health care for depression in a supermarket setting. Psychiatric Services 53:1132–1137, 2002Link, Google Scholar

6. Jindal RD, Friedman ES, Berman SR, et al: Effects of sertraline on sleep architecture in patients with depression. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 23:540–548, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 25:56–62, 1960Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Beck AT, Steer RA: Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, Psychological Corporation, 1993Google Scholar

9. Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK: The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 and the Service Satisfaction Questionnaire-30, in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment. Edited by Maruish M. Hillsdale, NJ, Earlbaum, 1994Google Scholar

10. Jacobson NS, Martell CR, Dimidjian S: Behavioral activation treatment for depression: returning to contextual roots. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice 8:255–270, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar