Child & Adolescent Psychiatry: The "Clock-Setting" Cure: How Children's Symptoms Might Improve After Ineffective Treatment

More than 50 years have passed since Eysenck's (1) provocative conclusion that "roughly two-thirds…will recover or improve…whether they are treated by means of psychotherapy or not." By now there is considerable evidence (2,3) that when some children receive psychotherapy under the right conditions their behavioral and emotional problems are improved. According to the results of one meta-analysis (4), the effect size for psychotherapy outcomes in controlled studies is large (.77). However, the authors of the analysis also reported that for traditional treatment in the community, the effect size was close to zero (.01). In a more recent randomized trial, Weiss and colleagues (5,6) found equal outcomes among treated and untreated children. These authors concluded that neither their data nor the literature supported the effectiveness of traditional child psychotherapy as currently practiced. Although psychotherapy has proven efficacy, its effectiveness for children and adolescents in the real world has yet to be demonstrated.

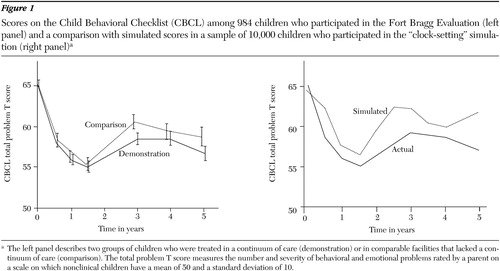

However, it is obvious that children with emotional and behavioral problems who receive treatment often improve. For example, a majority of the 984 children in the Fort Bragg Evaluation (7,8) improved during the 18 months after they started treatment, as can be seen in the five-year plot of Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL) scores in the left panel of Figure 1. The two curves in this panel describe two groups of children aged five to 17 years at intake who were treated in a continuum of care ("demonstration") or in comparable facilities that lacked a continuum of care ("comparison"). Some authors interpreted the early results as showing that traditional treatment, whether or not it was part of a continuum of care, was effective. For example Hoagwood (9) suggested, "The children in the Fort Bragg Demonstration Project improved. So did the children in the comparison sites…. An alternative conclusion is that the interventions were effective in both sites." This interpretation reflects a common-sense assumption that if treatment were ineffective, children would not get better.

But if it is true that current traditional treatment is ineffective, how could children improve? In the absence of a control group, natural history can masquerade as effectiveness. For example, traditional remedies for the common cold, such as hot lemonade, appear quite effective because the natural history is remission in seven to ten days. If you drink lemonade for a week, it works—your cold goes away! This remission requires no mystical placebos, expectancies, hope, or nonspecific curing agents—just the natural course of coryza. People often take something for a cold and feel better in a week.

We wanted to determine whether natural history could explain improvement in symptoms among children who receive ineffective treatment. We could not test this idea empirically with available data, so we conducted a Monte Carlo "thought experiment." The statistical simulation generates data sets based on explicit assumptions. Simulations can show that something could happen but not that it necessarily does happen.

The "clock-setting" simulation examined a population of 10,000 hypothetical children who were assessed each week for ten years with the CBCL. The population mean±SD score on the CBCL is 50±10. Scores of 65 or higher were considered clinical—that is, high enough for mental health treatment to be considered.

This simulation involved several assumptions. First, it was assumed that the problems of children vary over time in normally distributed frequencies and amplitudes that are unique to each child. Some children in the sample would average low or normal scores over time, whereas others would average borderline or high scores. Children with high average scores would resemble a clinical sample. Some children would show small variations of only a few points over time, whereas others would show large changes. Some would have rapid cycles of change over just a few weeks, whereas others would change much more slowly. There was only one thing all the children would have in common: over a ten-year period, not a single child would show any long-term improvement.

Second, it was assumed that children with high average scores are more likely to be referred for treatment than children with low scores. A third assumption was that referral to treatment is somewhat more likely when children reach their personal worst than at other times. Finally, it was assumed that treatment has no effect except that its beginning marks a special time in the child's natural history. More children who start treatment are near their personal worst rather than near their personal best.

After these assumptions were written into a computer program, parameters in the statistical model were adjusted to determine whether the model could simulate actual five-year seven-wave CBCL scores from the Fort Bragg Evaluation. The comparison of simulated and actual scores is shown in the right panel of Figure 1. The similarity between the actual and simulated scores suggests that it is possible to see a large initial improvement after the start of an ineffective treatment. How do we interpret these results?

Although each child has an independent time line, researchers often set time zero as the time when the parent brought the child for treatment. This "clock setting" synchronizes unrelated children. Consider a clinic's waiting room when it is full of intakes. More of these children are near their personal worst than would be true at other times. After some weeks or months, these children would be better—that is, no longer at their worst. This clock-setting cure is like drinking hot lemonade for a cold and feeling better in a week—both are effects of natural history.

The statistical simulation, of course, does not prove that clock-setting cures actually occur among children. However, it does suggest that the initial improvement in the longitudinal outcome curve in the Fort Bragg Evaluation represents natural improvement rather than the effects of treatment. It is possible that neither effective treatments nor placebos that cure by hope were responsible for the outcomes of these 984 treated children.

There is no contradiction between the fact that children improved after beginning treatment and the suggestion that traditional child psychotherapy may be ineffective. Natural changes among children over time could explain large improvements in the absence of effective treatment. To determine whether clock setting really occurs would require longitudinal studies of complete populations measured frequently for very long periods.

The authors are affiliated with the Center for Mental Health Policy, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, 1207 18th Avenue South, Nashville, Tennessee 37212 (e-mail, [email protected]). Charles Huffine, M.D., is editor of this column.

Figure 1. Scores on the Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL) among 984 children who participated in the Fort Bragg Evaluation (left panel) and a comparison with simulated scores in a sample of 10,000 children who participated in the "clock-setting" simulation (right panel)a

a The left panel describes two groups of children who were treated in a continuum of care (demonstration) or in comparable facilities that lacked a continuum of care (comparison). The total problem T score measures the number and severity of behavioral and emotional problems rated by a parent on a scale on which nonclinical children have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.

1. Eysenck HJ: The effects of psychotherapy: an evaluation. Journal of Consulting Psychology 16:319–324, 1952Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Casey RJ, Berman JS: The outcome of psychotherapy with children. Psychological Bulletin 98:388–400, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Weisz JR, Weiss B, Han SS, et al: Effects of psychotherapy with children and adolescents revisited: a meta-analysis of treatment outcome studies. Psychological Bulletin 117:450–468, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Weisz JR, Donenberg GR, Weiss B, et al: Bridging the gap between laboratory and clinic in child and adolescent psychotherapy: efficacy and effectiveness in studies of child and adolescent psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 63:688–701, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Weiss B, Catron T, Harris V: A two-year follow-up of the effectiveness of traditional child psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68:1094–1101, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Weiss B, Catron T, Harris V, et al: The effectiveness of traditional child psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67:82–94, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Bickman L, Guthrie PR, Foster EM, et al: Evaluating Managed Mental Health Services: The Fort Bragg Experiment. New York, Plenum, 1995Google Scholar

8. Bickman L: A continuum of care: more is not always better. American Psychologist 51:689–701, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hoagwood K: Interpreting nullity: the Fort Bragg experiment: a comparative success or failure? American Psychologist 52:546–550, 1997Google Scholar