Brief Reports: Use of Health Care Services and Costs of Psychiatric Disorders Among National Health Insurance Enrollees in Taiwan

Abstract

The National Health Insurance (NHI) database in Taiwan was used to detect the use of health care services and the costs of psychiatric disorders among NHI enrollees. Data were analyzed for 126,146 enrollees. Four categories were used for enrollees: no psychiatric disorder, a minor psychiatric disorder, a major psychiatric disorder without catastrophic illness registration, and a major psychiatric disorder with catastrophic illness registration (which eliminates copayments). Compared with enrollees with a minor psychiatric disorder, those with a major psychiatric disorder, either with or without catastrophic illness registration, had higher use and costs of mental health care services. Compared with enrollees without a psychiatric disorder, those with a minor psychiatric disorder or a major psychiatric disorder without catastrophic illness registration had higher use and costs of non-mental health care services. Both the mental and general health care of persons with psychiatric disorders are important.

In 1990 about five million persons in the United States (2.8 percent of the total population) had severe mental disorders, which cost $20 billion, or about 4 percent of total direct health care costs (1). A study of a community cohort of individuals with major depression showed that just 4.9 percent of the treated patients accounted for 45 percent of outpatient expenditures for depression treatment, which indicates that patients with severe mental disorders account for a large part of mental health care expenditures (2). Also, several studies that were conducted in the United States revealed that Medicaid and Medicare enrollees with psychiatric disorders had significantly higher use and costs of health care services than enrollees without mental illness; most of these costs were associated with non-mental health care services (3,4).

Although the cost and use of mental health services in the United States is well documented, little is known about these issues in Taiwan. In March 1995 Taiwan implemented a National Health Insurance (NHI) program, which offered general health insurance to all citizens. Ninety-six percent of all residents of Taiwan (21,400,826 persons) were enrolled in the NHI in 2000 (5). We used data from the NHI to determine the use of health care services and the costs of different types of psychiatric disorders among enrollees.

Methods

The National Health Research Institute has a database that contains information on 200,432 NHI enrollees, about 1 percent of the population of Taiwan, who were chosen for the database at random. The database has been used for related studies (5). Enrollees were excluded from our study if they were born in another country or if they had not been alive and continuously eligible for the NHI for all of 2000. As a result of these criteria, 30,106 persons were excluded. An additional 44,180 enrollees were excluded from our study because they were younger than 18 years. The final sample consisted of 126,146 persons.

We divided the enrollees into four groups: no psychiatric disorder (119,092 enrollees, or 94 percent), a minor psychiatric disorder (5,262 enrollees, or 4 percent), a major psychiatric disorder without catastrophic illness registration (1,041 enrollees, or 1 percent), and a major psychiatric disorder with catastrophic illness registration (751 enrollees, or 1 percent). Each enrollee with a principal diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder was classified according to International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic criteria (6). Minor psychiatric disorders include ICD-9-CM codes 300 through 316, excluding 303 through 305 and 312 through 315 (neurotic disorders, personality disorders, sexual deviations and disorders, physiological malfunction arising from mental factors, special symptoms or syndromes, acute reaction to stress, adjustment reaction, specific nonpsychotic mental disorders due to organic brain damage, depressive disorder not elsewhere classified, and psychic factors associated with diseases classified elsewhere) (5). Major psychiatric disorders include ICD-9-CM codes 290 through 298 (senile and presenile organic psychotic conditions, alcoholic psychoses, drug psychoses, transient organic psychotic conditions, other organic psychotic conditions, schizophrenic disorders, affective psychoses, paranoid states, and other nonorganic psychosis) (5). In Taiwan enrollees with several kinds of major psychiatric disorders, including ICD-9-CM codes 290 and 293 through 297 (senile and presenile organic psychotic conditions, transient organic psychotic conditions, other organic psychotic conditions, schizophrenic disorders, affective psychoses, and paranoid states) can apply for catastrophic illness registration (5). Enrollees with this registration do not need to pay copayments when they seek mental health care. All service claims were classified into mental health services or non-mental health services, according to the category of principal diagnosis.

NHI beneficiaries are required to pay a portion of medical costs to encourage the conscientious and efficient use of medical resources, thereby preventing waste and misuse. To ease the financial burden on the public, ceilings on copayment have been placed. If an enrollee spends fewer than 30 days in the acute ward or 180 days in the chronic ward, the ceiling on copayment is $24,000 per admission (costs are given in New Taiwan dollars). The upper ceiling of copayment for the entire calendar year is $40,000. The copayment rates for outpatient care range from $50 to $420 per visit, according to the level of service provided.

Patients with catastrophic illness registration for psychiatric disorders do not pay copayments when they seek mental health care, although they still must pay them for non-mental health services. If there was not a catastrophic illness registration system, it is possible that the copayment would be high enough to prevent many people with major psychiatric disorders from seeking care.

The mean±SE number of outpatient visits and inpatient days and the mean costs of outpatient and inpatient treatment in 2000 were calculated for each of the four groups. We used an analysis of covariance to control for age and sex (7). Use and costs of health services were adjusted by age and sex for the four groups, and the differences the groups were tested. SAS version 8.0 was used to link and analyze the data. The significance level was set at p=.01.

Results

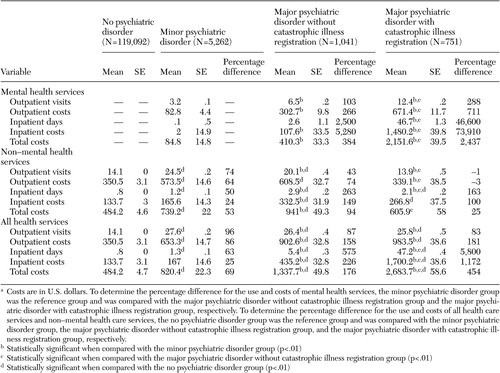

Table 1 shows the mean±SE annual use and costs of health care services for each of the four groups of psychiatric disorders, adjusted by age and sex. For the use and costs of mental health care services, enrollees with a major psychiatric disorder who did not have catastrophic illness registration had significantly more outpatient visits as well as significantly higher outpatient and inpatient costs and total costs than those with a minor psychiatric disorder. Enrollees with a major psychiatric disorder who had catastrophic illness registration had significantly higher use and costs of mental health care services than those with a minor psychiatric disorder and those with a major psychiatric disorder who did not have catastrophic illness registration. The average annual costs of mental health care services for the minor psychiatric disorders group, the major psychiatric disorders without catastrophic illness registration group, and the major psychiatric disorders with catastrophic illness registration group were $85, $410, and $2,152, respectively (costs are given in U.S. dollars).

For the use and costs of non-mental health care services, enrollees with a minor psychiatric disorder had significantly more outpatient visits and inpatient days as well as significantly higher outpatient and total costs than those without a psychiatric disorder. Enrollees with a major psychiatric disorder who did not have catastrophic illness registration had significantly higher use and costs of non-mental health care services than those without a psychiatric disorder. Enrollees with a major psychiatric disorder who did not have catastrophic illness registration had significantly more outpatient visits and inpatient days as well as significantly higher inpatient costs, and total costs than those with a minor psychiatric disorder. The average annual costs of non-mental health services for an enrollee in the group with no psychiatric disorder, the minor psychiatric disorder group, the major psychiatric disorder without catastrophic illness registration group, and the major psychiatric disorder with catastrophic illness registration were $484, $739, $941, and $606, respectively (costs are given in U.S. dollars).

Discussion

This is the first study that analyzed the use of health care services and the costs of psychiatric disorders in Taiwan by using the random sampling files offered by the National Health Research Institute. Our results indicate that the use and costs of health care services vary according to whether an enrollee has a psychiatric disorder and what kind of psychiatric disorder he or she has.

In our sample, the average annual costs of mental health services for an enrollee in the group with minor psychiatric disorders, the group with major psychiatric disorders without catastrophic illness registration, and the group with major psychiatric disorders with catastrophic illness registration were $85, $410, and $2,152, respectively (costs are given in U.S. dollars). These differences in costs of mental health services demonstrate the effect of the type and severity of disease and of the presence of catastrophic illness registration. Higher needs, greater symptom severity, and longer psychiatric history are associated with higher costs, as was shown in a study performed in European countries (8). Our study showed that enrollees with a major psychiatric disorder who have catastrophic illness registration have costs for health care services that are five times as high as costs for enrollees with a major psychiatric disorder who did not have catastrophic illness registration. Also, patients with a major psychiatric disorder who had catastrophic illness registration had an average of 12 outpatient visits during 2000, about one visit every month, which reflects the effect that catastrophic illness registration has on mental health expenditures and use.

The average annual costs of non-mental health care services for an enrollee in the group with no psychiatric disorders, the group with minor psychiatric disorders, the group with major psychiatric disorders without catastrophic illness registration, and the group with major psychiatric disorders with catastrophic illness registration were $484, $739, $941, and $606, respectively (costs are given in U.S. dollars). Our data imply that enrollees with a minor psychiatric disorder or a major psychiatric disorder without catastrophic illness registration tend to have higher use and costs of non-mental health care services than those without a psychiatric disorder, which is consistent with previous studies that have used Medicaid, Medicare, and other claims data (3,4). Four factors—age, the fact that persons who enter the health care system for one reason are more likely to be screened for other conditions (detection), the fact that persons who are high users of services are likely to be thought of as hypochondriacs and referred for psychiatric care (labeling), and the fact that anxiety and depression are commonly associated with and diagnosed with physical disorders (association)—have been associated with the high use of general health care services among persons with mental illness (9). In our study, when we controlled for age and sex (Table 1), enrollees with a minor psychiatric disorder or a major psychiatric disorder without catastrophic illness registration had higher use and costs of non-mental health care services than those without a psychiatric disorder; thus we conclude that age alone does not explain the higher costs. Usually, enrollees with mental illness have more nonspecific complaints and receive more medical tests, which lead to higher use and costs of health care services (4). Also, persons with a high use of medical services are sometimes categorized as hypochondriacs and referred for psychiatric care (9). It is possible that the detection, association, and labeling could account for the higher cost of health care services among enrollees with mental illness (9). Several factors should be considered when investigating the reason for this higher cost, such as clinical history, comorbid physical and mental illnesses, social network, and other personal characteristics (10).

Conclusions

Enrollees with a major psychiatric disorder, either with or without catastrophic illness registration, have higher use and costs of mental health care services than those with a minor psychiatric disorder. This finding could be due to two reasons: enrollees with catastrophic illness registration have a high severity of illness, which could account for the high use and costs, and those with catastrophic illness registration get free care and therefore use more services. Enrollees with a minor psychiatric disorder or a major psychiatric disorder who do not have catastrophic illness registration have higher use and costs of non-mental health care services than those without a psychiatric disorder. In addition to mental illness education, prevention, and treatment, the general health care of persons with psychiatric disorders is important.

Dr. Chien, Dr. Y. J. Chou, Mr. Lin, and Dr. P. Chou are affiliated with the Institute of Public Health at National Yang Ming University in Taipei, Taiwan. Dr. Chien is also with the Tsao-Tun Psychiatric Center in Nan-Tou, Taiwan. Dr. Bih is with the Bali Mental Hospital in Taipei. Dr. Chang is with the Department of Health in Taipei and with the Institute of Health and Welfare at National Yang Ming University in Taipei. Send correspondence to Dr. P. Chou at the Institute of Public Health at National Yang Ming University, 155 Li-Nong Street, Section 2, Peitou, Taipei, Taiwan 112 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Average use and costs of health care services for a National Health Insurance enrollee in Taiwan during 2000, adjusted by age and sexa

a Costs are in U.S. dollars. To determine the percentage difference for the use and costs of mental health services, the minor psychiatric disorder group was the reference group and was compared with the major psychiatric disorder without catastrophic illness registration group and the major psychiatric disorder with catastrophic illness registration group, respectively. To determine the percentage difference for the use and costs of all health care services and non-mental health care services, the no psychiatric disorder group was the reference group and was compared with the minor psychiatric disorder group, the major psychiatric disorder without catastrophic illness registration group, and the major psychiatric disorder with catastrophic illness registration group, respectively.

1. Health care reform for Americans with severe mental illnesses: report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1447–1465, 1993Link, Google Scholar

2. Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, et al: Expenditures for the treatment of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:883–888, 1998Link, Google Scholar

3. Husaini BA, Levine R, Summerfelt T, et al: Prevalence and cost of treating mental disorders among elderly recipients of Medicare services. Psychiatric Services 51:1245–1247, 2000Link, Google Scholar

4. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al: Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:352–357, 1995Link, Google Scholar

5. Chien IC, Chou YJ, Lin CH, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among National Health Insurance enrollees in Taiwan. Psychiatric Services 55:691–697, 2004Link, Google Scholar

6. ICD-9-CM English-Chinese Dictionary. Taipei, Chinese Hospital Association Press, 2000Google Scholar

7. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE, et al: Analysis of covariance and other methods for adjusting continuous data, applied regression analysis, and other multivariable methods, 3rd ed. Pacific Grove, Calif, Duxbury Press, 1998Google Scholar

8. Knapp M, Chisholm D, Leese M, et al: Comparing patterns and costs of schizophrenia care in five European countries: the EPSILON study: European Psychiatric Services: Inputs Linked to Outcome Domains and Needs. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 105:42–54, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Liptzin B, Regier DA, Goldberg ID: Utilization of health and mental health services in a large insured population. American Journal of Psychiatry 137:553–558, 1980Link, Google Scholar

10. Amaddeo F, Beecham J, Bonizzato P, et al: The use of a case register to evaluate the costs of psychiatric care. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 95:189–198, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar