Depression, Anxiety, and Physical Impairments and Quality of Life in the U.S. Noninstitutionalized Population

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to examine health-related quality of life and health behaviors among persons reporting a primary mental health impairment compared with those reporting a primary physical health impairment and those reporting no impairment. METHODS: Data were obtained from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an ongoing state-based, random-digit telephone survey of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population aged 18 years or older. In 2001-2002, health-related quality-of-life measures were administered in 23 states and the District of Columbia. RESULTS: An estimated 5.1 percent of U.S. adults reporting a primary health impairment indicated that a mental health problem was the primary cause. Those with a primary mental health impairment were more likely than those with a primary physical health impairment to report infrequent vitality (less than 14 days in the previous 30 days) and frequent occurrences of mental distress, depressive symptoms, and anxiety (at least 14 days in the previous 30 days). Relative to those who reported no impairment, persons who reported a mental health impairment were more likely to indicate that they experienced frequent physical distress and frequent pain. Persons with a primary mental health impairment were more likely than those with a primary physical health impairment to smoke and drink heavily. No significant difference was found in self-reported frequent sleeplessness or fair-to-poor general health between persons with a primary mental health impairment and those with a physical health impairment. CONCLUSIONS: Mental health impairment is strongly associated with reduced health-related quality of life and health behaviors, frequently at levels equal to or exceeding those of physical health impairments.

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability in the United States, affecting an estimated 9.5 percent of Americans aged 18 years or older annually (1). Highly prevalent among persons with heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes, depression is associated with an increased risk of subsequent physical illness, disability, and premature mortality (2). Compared with persons who do not have depressive symptoms, those with depressive symptoms—even at levels that do not warrant a diagnosis of major depression—experience more unemployment (3), make greater use of mental health services, have poorer self-perceived emotional health, and attempt suicide more frequently (4). In addition, depression adversely affects physical functioning and pain perception (5).

Anxiety disorders are also highly prevalent. A community-based investigation found that more than 6 percent of men and 13 percent of women had suffered from an anxiety disorder in the previous six months (6). Anxiety disorders are also associated with considerable functional impairment and disability (7) and have been linked to unemployment and chronic illness (8). Moreover, among persons with medical conditions, anxiety is associated with a fourfold increased duration of disability than is characteristic of persons who do not have anxiety (9).

Emotional states, including anxiety and depressive disorders, influence individuals' assessment of their ability to adopt and maintain health-enhancing behaviors (10) and influence vulnerability to illness (11). Research conducted in clinical settings has shown that anxiety and depressive disorders are associated with impairment in functioning at levels equal to or exceeding those of the effects of common physical conditions, such as lower-back pain, arthritis, diabetes, and heart disease (12,13).

In addition, a study by Ormel and colleagues (14) indicated that psychopathology is associated with increased disability, even after adjustment for the severity of physical disease. The importance of mental health to well-being is also attested to by the finding that an estimated 33 percent of Americans who reported disabilities indicated that a mental health condition was a contributing factor (15). These findings stand in contrast with the traditional focus of the biomedical model of disease, which characteristically minimalizes the importance of psychological and emotional status to health (16,17).

The purpose of this study was to examine health-related quality of life and health behaviors among persons reporting a primary mental health impairment compared with those who reported a primary physical health impairment and those who reported no impairment.

Methods

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is an ongoing state-based, random-digit telephone survey of noninstitutionalized persons aged 18 years or older in the United States, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The BRFSS monitors the prevalence of key health- and safety-related behaviors and characteristics (18). In 2001 and 2002, trained interviewers administered standardized quality-of-life questions in a total of 23 states—Alaska, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, and Utah in 2001, and Alabama, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Virginia, and Wisconsin in 2002—and the District of Columbia. Each state is represented once. If a state was included in both the 2001 and 2002 surveys, we analyzed data from the 2002 survey only. BRFSS methods, including its weighting procedure, are described elsewhere (19). The study was approved by the internal review board of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (protocol 2988) as meeting the criteria for appropriate consent in survey research.

To be included in our analysis, the respondent must have answered two disability-related questions: Are you limited in any way in any activities because of physical, mental, or emotional problems? and, Do you have a health problem that requires you to use special equipment, such as a cane, a wheelchair, a special bed, or a special telephone? Those who responded "yes" to either question were then asked, What is your major impairment or health problem? Responses to this question were categorized as arthritis or rheumatism; back or neck problems; fractures; bone or joint injury; walking problems; lung or breathing problems; hearing problems; eye or vision problems; heart problems; stroke; hypertension or high blood pressure; diabetes; cancer; depression, anxiety, or emotional problems; and other impairments or problems. Respondents could indicate only one primary impairment. Those who reported depression, anxiety, or emotional problems as their primary impairment or health problem were defined as having a primary mental health impairment. Those who reported that their primary impairment or health problem was attributable to a physical health problem were categorized as having a primary physical health impairment. Respondents who answered "no" to the question about limitations in activities because of physical, mental, or emotional problems and "no" to both disability-related questions were considered to have no primary impairment or health problems.

We examined eight health-related quality-of-life questions that have demonstrated validity and reliability for population health surveillance (20). Respondents were asked to rate their general health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. These response categories were dichotomized into excellent, very good, and good in one category and fair and poor in the other category. Seven additional questions were asked that referred to the preceding 30 days: How many days was your physical health, which includes physical illness or injury, not good? (physical distress); How many days was your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, not good? (mental distress); How many days did pain make it difficult to do your usual activities? (pain); How many days did you feel sad, blue, or depressed? (depressive symptoms); How many days did you feel worried, tense, or anxious? (anxiety); How many days did you feel you did not get enough rest or sleep? (sleeplessness); and How many days did you feel very healthy and full of energy? (vitality). In each domain, responses were dichotomized into less than 14 days (infrequent) and 14 days or more (frequent). This division, in addition to being used in previous research (21,22,23), was selected because it roughly parallels clinical indicators of depressive disorders (24) and describes the respondent's status for a substantial portion of the month.

The BRFSS also provides information about three modifiable risk behaviors: smoking, physical inactivity, and heavy drinking. Respondents were considered to be current smokers if they reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smoked every day or on some days. Those who formerly smoked or never smoked were considered nonsmokers. Respondents were considered to be physically inactive if they responded "no" to the question, During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening or walking for exercise? Finally, heavy drinking was defined as more than one drink a day for women and more than two drinks a day for men.

A total of 18,064 participants reported a primary impairment or health problem, 902 of whom reported a primary mental health impairment. An additional 80,310 respondents reported no major impairment or health problem. SUDAAN software, release 8.0.0, was used in the analyses to take into account the complex sample design and to calculate prevalence estimates, 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs), and adjusted odds ratios (ORs). All models were adjusted for sex, age, race or ethnicity, marital status, education, and employment status.

Results

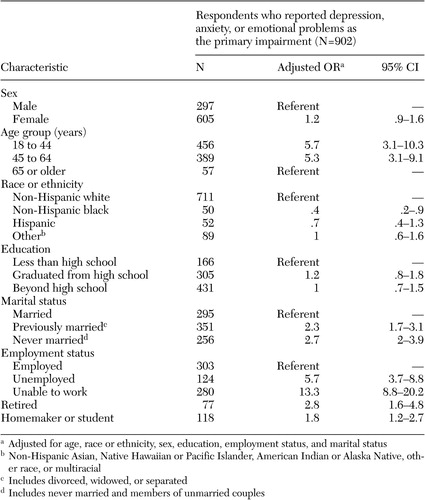

Table 1 shows the odds of reporting a primary mental health impairment by demographic characteristic. Persons aged 18 to 44 years and those aged 45 to 64 years were at significantly greater risk of having a primary mental health impairment than those aged 65 years or older. In addition, non-Hispanic whites were significantly more likely to report a primary mental health impairment than non-Hispanic blacks. Those who were previously married or never married were also more likely to report a primary mental health impairment than those who were currently married, and those who were currently employed were less likely to report a mental health impairment than those who were unemployed, unable to work, retired, or a homemaker or student.

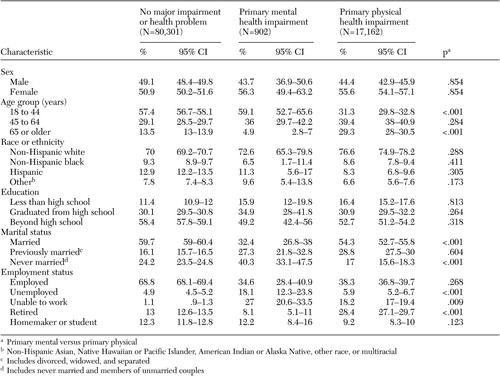

Approximately 5.1 percent of persons who reported a health impairment (95 percent confidence interval [CI]=4.4 to 5.7 percent) selected depression, anxiety, or problems with emotions as the primary cause. Demographic characteristics of respondents who reported no impairment or health problem, a primary mental health impairment, or a primary physical health impairment are summarized in Table 2. Adults aged 18 to 44 years were more likely to report a primary mental health impairment than a primary physical health impairment, whereas those aged 65 years or older were more likely to report a primary physical health impairment. Respondents who had never been married were more likely to report a primary mental health impairment, whereas those who were currently married were more likely to report a physical health impairment. Finally, adults who reported that they were unemployed or unable to work were more likely to report a mental health impairment, whereas those who were retired were more likely to report a physical health impairment.

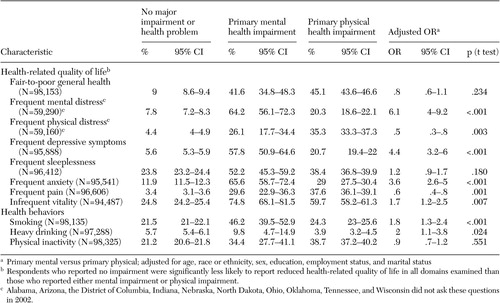

Table 3 shows health-related quality of life and health behaviors among those with no impairment, those with a primary mental health impairment, and those with a primary physical health impairment. After adjustment for sociodemographic covariates, we found that respondents with a primary mental health impairment were significantly more likely than those with a primary physical health impairment to report frequent mental distress, frequent depressive symptoms, frequent anxiety, and infrequent vitality. Respondents who reported a primary physical health impairment were significantly more likely to report frequent physical distress and frequent pain. However, those with a primary mental health impairment were significantly more likely than those with no impairment to report frequent physical distress (p<.001) and frequent pain (p<.001). Notably, those who reported a primary mental or physical impairment were equally as likely to report fair-to-poor general health and frequent sleeplessness. Results further indicate that persons in the nonimpaired group were significantly less likely to report reduced health-related quality of life in all domains examined than those with either a physical or mental health impairment.

Finally, adjusted logistic models indicated that adults who reported a primary mental health impairment were 1.8 times as likely to smoke and two times as likely to drink heavily as those who reported a primary physical health impairment (Table 3). Notably, those who reported a mental health-related impairment were as unlikely to exercise as those who reported a physical health-related impairment. Smoking and physical inactivity were significantly more prevalent among respondents who reported either a primary mental or physical health impairment than among those who reported no impairment. However, compared with respondents who reported no impairment, those who reported a physical impairment were less likely to be categorized as heavy drinkers.

Discussion and conclusions

An estimated 53 million persons in the United States have at least one disability (25). Among adults who reported a primary impairment in our study, approximately 5.1 percent reported a mental health problem as the primary cause. As might be expected, we found that persons with a mental health-related impairment were significantly more likely than those with a physical health-related impairment to report frequent mental distress, frequent depressive symptoms, frequent anxiety, and infrequent vitality, which provides support for the construct validity of the measure.

Furthermore, our data support the findings of Saarijärvi and colleagues (5) that depression has an impact on physical functioning, pain, and general health perceptions. Compared with respondents with no impairment, those with physical health-related impairments and those with mental health-related impairments were both significantly more likely to report frequent physical distress and frequent pain. No significant difference was found between those who reported primary mental health impairment and those who reported primary physical health impairment with regard to reported fair-to-poor general health and frequent sleeplessness.

Our results also suggest the importance of mental health-related impairments to health risk behaviors. Corroborating previous research, we found associations between both smoking and alcohol consumption and the occurrence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, or emotional problems (26,27). In the prospective Stirling County Study, which was designed to examine the associations between depression and smoking, investigators found that participants who were depressed were more likely to initiate smoking and continue smoking and less likely to quit smoking than those who had never been depressed (28).

These relationships are not fully understood, but research suggests that they may be mediated by genetic or environmental factors or a desire to self-medicate (27,29,30). In addition, dysphoric mood decreases people's beliefs that they can adopt and maintain health-promoting behaviors, such as not smoking or initiating smoking cessation (10). Thus our results further suggest the potential importance of treating mood disorders as a means of minimizing substance abuse and dependence.

Our study had several limitations. Because the BRFSS is a telephone survey, it excludes some groups without telephones who are known to have higher prevalences of mental illness and disability, such as persons of lower socioeconomic status (3). In addition, because our analysis was based on data from only 23 states and the District of Columbia, our results may not be representative of the entire United States. In addition, we could not fully examine the potential effect of comorbid illness, because our survey did not collect such information. We must also consider the possibility that persons with severely impaired physical or mental health would not have been able to complete the survey. Furthermore, the data we analyzed were self-reported and were not validated by physical or psychiatric examination. Finally, our data were cross-sectional, and thus we were unable to determine causal relationships between type of impairment (physical, mental, or none), health behaviors, and health-related quality of life.

These limitations notwithstanding, our data reveal that symptoms of depression and anxiety, in addition to being distressing to the affected individual, are disabling and are often associated with adverse health behaviors. Our results are consistent with the results of previous research conducted in clinical populations (12,13) and verify the impact of mental health on health-related quality of life and health behaviors in the community. Specifically, although a primary mental health impairment is associated with an expected deleterious effect on mental health indicators, it is also highly predictive of adverse effects on physical health. Given that depression is expected to be second only to heart disease as a source of the global burden of disease by the year 2020 (31), a better understanding of barriers to its recognition and treatment appears vital to increasing the quality and duration of life for the U.S. population (32).

The authors are affiliated with the division of adult and community health of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Send correspondence to Ms. Strine at 4770 Buford Highway, N.E., Mailstop K-66, Atlanta, Georgia 30341 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Odds of primary mental health impairment among persons aged 18 years or older, by demographic characteristics, 2001-2002

|

Table 2. Prevalence of various sociodemographic characteristics among persons aged 18 years or older, by primary impairment type, 2001-2002

|

Table 3. Prevalence of impaired health-related quality of life and various adverse health behaviors among persons aged 18 years or older, by primary impairment type, 2001-2002

1. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85–94, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Gaynes BN, Burns BJ, Tweed DL, et al: Depression and health-related quality of life. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190:799–806, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Whooley MA, Kiefe CI, Chesney MA, et al: Depressive symptoms, unemployment, and loss of income: the CARDIA Study. Archives of Internal Medicine 162:2614–2620, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Judd LL, Paulus MP, Wells KB, et al: Socioeconomic burden of subsyndromal depressive symptoms and major depression in a sample of the general population. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1411–1417, 1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Saarijärvi S, Salminen JK, Toikka T, et al: Health-related quality of life among patients with major depression. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 56:261–264, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Leon AC, Portera L, Weissman MM: The social costs of anxiety disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement 166 (suppl 27):19–22, 1995Google Scholar

7. Wittchen HU: Generalized anxiety disorder: prevalence, burden, and cost to society. Depression and Anxiety 16:162–171, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wittchen HU, Hoyer J: Generalized anxiety disorder: nature and course. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62(suppl 11):15–19, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

9. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al: Self-reported anxiety, general medical conditions, and disability bed days. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1766–1768, 1997Link, Google Scholar

10. Bandura A: Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, Freeman, 1997Google Scholar

11. National Research Council: Predisease pathways, in New Horizons in Health: An Integrative Approach. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001Google Scholar

12. Schonfeld WH, Verboncoeur CJ, Fifer SK, et al: The functioning and well-being of patients with unrecognized anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 43:105–119, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, et al: Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:11–19, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun TB, et al: Common mental disorders and disability across cultures: results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA 272:1741–1748, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Druss BG, Marcus SC, Rosenheck RA, et al: Understanding disability in mental and general medical conditions. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1485–1491, 2000Link, Google Scholar

16. Engel GL: The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196:129–136, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Stroebe W: Changing conceptions of health and illness, in Social Psychology and Health. Buckingham, Philadelphia, Open University Press, 2000Google Scholar

18. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System User's Guide. Atlanta, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998. Available at www.cdc.gov/brfss/technical_infodata/users guide.htmGoogle Scholar

19. Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH: Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment: recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 52(RR-9):1–12, 2003Google Scholar

20. Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Kobau R: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Healthy Days Measures: population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 1:37–45, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Ford ES, Mannino DM, Homa DM, et al: Self-reported asthma and health-related quality of life: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Chest 123:119–127, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Ahluwalia IB, Holtzman D, Mack KA, et al: Health-related quality of life among women of reproductive age: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 1998–2001. Journal of Women's Health 12:5–10, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Okoro CA, Brewer RD, Naimi TS, et al: Binge drinking and health-related quality of life: do popular perspectives match reality? American Journal of Preventive Medicine 26:230–233, 2004Google Scholar

24. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

25. McNeil J: Americans With Disabilities:1997. Current Population Reports, series P70–73. Washington, DC, Bureau of the Census, 2001 Available at www.census.gov/ prod/2001pubs/p70–73.pdfGoogle Scholar

26. Stein MB: Advances in recognition and treatment of social anxiety disorder: a 10-year retrospective. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 37(suppl 1):97–107, 2003Medline, Google Scholar

27. Hämäläinen J, Kaprio J, Isometsä E, et al: Cigarette smoking, alcohol intoxication, and major depressive episode in a representative population sample. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 55:573–576, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Murphy JM, Horton NJ, Monson RR, et al: Cigarette smoking in relation to depression: historical trends from the Stirling County Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1663–1669, 2003Link, Google Scholar

29. Dierker LC, Avenevoli S, Stolar M, et al: Smoking and depression: an examination of mechanisms of comorbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:947–953, 2002Link, Google Scholar

30. Patton GC, Hibbert M, Rosier MJ, et al: Is smoking associated with depression and anxiety in teenagers? American Journal of Public Health 86:225–230, 1996Google Scholar

31. Murray CJL, Lopez AD: The Global Burden of Disease. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

32. US Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2010, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 2000Google Scholar