One-Year Follow-up of a Multiple-Family-Group Intervention for Chinese Families of Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study tested the effectiveness of a mutual support multiple-family-group intervention for schizophrenia in terms of improvements in patients' psychosocial functioning, use of mental health services, and rehospitalization compared with a psychoeducation intervention and standard care. METHODS: A controlled trial was conducted in a sample of 96 Chinese families who were caring for a relative with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. The families were randomly assigned to one of three groups: mutual support (N=32), psychoeducation (N=33), and standard care (N=31). The interventions were delivered at two psychiatric outpatient clinics over a six-month period. The mutual support and psychoeducation interventions consisted of 12 group sessions every two weeks, each lasting about two hours. The mutual support group was a peer-led group designed to provide information, emotional support, and coping skills for caregiving in stages. The psychoeducation group was a professional-led group designed to educate families about the biological basis of schizophrenia and treatment and to improve illness management and coping skills. The standard care group and the other two groups received routine psychiatric outpatient care during the intervention. Data analyses of multiple outcomes over one-year follow-up were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. RESULTS: Multivariate analyses of variance showed that the mutual support intervention was associated with consistently greater improvements in patients' functioning and rehospitalization and stable use of mental health services over the follow-up period compared with the other two interventions. CONCLUSIONS: The study provides evidence that mutual support groups can be an effective family intervention for Chinese persons with mental illness in terms of improving patients' functioning and hospitalization without increasing their use of mental health services.

As in Western countries, more than 40 percent of people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong live with their families while still depending on access to community care (1,2). The effect of family intervention has consistently been shown to enhance knowledge about the illness, reduce relapse rates, and improve compliance with medication regimens (3).

Despite challenges raised by some recent reviews (3,4,5,6), studies in mainland China and Western countries have demonstrated that family psychoeducation that spans at least nine months is more effective in the prevention of relapse among persons with schizophrenia than is individual treatment or medication alone. The common elements in several approaches of effective family psychoeducation programs and in the recommendation of the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) include social support, education about the illness and its treatment, guidance and resources during crisis, and training in problem solving (7,8). However, little is known about the major therapeutic components of psychoeducation and other psychosocial family interventions for schizophrenia (3,4).

Recent studies suggest that clinicians' hesitation to use family intervention may be related to concerns about the experience and training required to become a therapist (8,9) and the extent to which the family intervention is connected to routine care. In addition, most family intervention studies have focused on Caucasian populations; few studies have included Hispanic and Asian participants (9,10). Thus it is unclear whether interventions that are accepted practice in Western countries can be applied successfully to a Chinese family-oriented culture.

The proliferation of support groups in Western countries in the 1990s was part of a larger social movement of self-help organizations for people affected by chronic diseases whose needs were being inadequately addressed by conventional health care (2,11). Increasing research evidence indicates that peer support within family groups is associated with considerable improvement in psychological adjustments by families with a relative who has chronic mental illness (11). The Treatment Strategies for Schizophrenia study also found that supportive family management, whose key elements are comparable to those of a mutual support group, was associated with significant improvements in patient functioning similar to that seen with behavioral family management (12,13). Support groups require less intensive training for health professionals to serve as facilitators compared with other treatment approaches, and they provide a flexible, interactive client-directed approach to help families cope with their caregiving role. However, there is little empirical evidence to support enthusiastic claims that peer support alone contributes to improved patient and family functioning or rehospitalization and relapse, because few family support groups have been rigorously studied and systematically evaluated (4).

In helping a Chinese family that has a relative with a mental illness, it is important to respect culture-specific family structures, functions, and processes—for example, the extended family structure and the close interdependence of the relationships within it and the strong sense of filial responsibility and mutual support—and to use these in group interventions (14,15). The study reported here aimed to compare the effectiveness of three methods of family intervention for Chinese patients with schizophrenia. The main hypotheses were that the mutual support group embedded in psychiatric outpatient services would significantly reduce the number of hospitalizations among the patients and would improve psychosocial functioning and use of mental health services by their families compared with the psychoeducation and standard care groups.

Methods

Participants

A randomized controlled trial with a three-group repeated-measures design was used. The study was undertaken between January 2002 and July 2003, and the participants were followed up over a 12-month period afterwards. Participants were selected randomly from the patient lists of two regional outpatient clinics in Hong Kong, which contained about 1,500 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (10 percent of the target population) (16).

A total of 300 Chinese families (20 percent) who were caring for a relative with schizophrenia from these outpatient clinics were eligible to participate, provided that they met the following inclusion criteria: they lived with and cared for one relative with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, according to DSM-IV criteria, for not more than five years (that is, their relative had less chronic illness); their relative with schizophrenia had no comorbid mental illness or substance abuse at baseline; and they were at least 18 years old and could understand the Chinese language. Potential participants were excluded if they cared for more than one family member with mental illness or if they had been the primary caregiver for less than three months. For patients with more than one caregiver, the family member who had the major caring role was indicated by the patient and recruited. Written consent was obtained from 146 families, of whom 96 (66 percent) were randomly selected and assigned to one of the three study groups: mutual support (N=32), psychoeducation (N=33), and standard care (N=31). The remaining 50 families, who had been informed about the possibility of not being selected for the study, were placed on a waiting list because of time and manpower constraints on group formation.

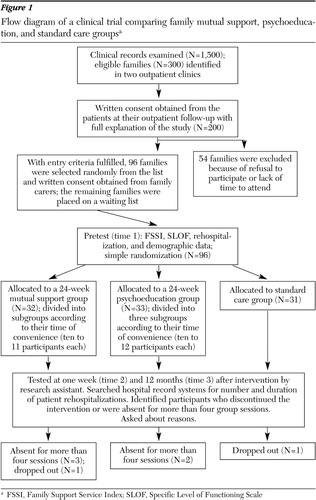

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the outpatient clinics. Recruitment, treatments, measurements, and data analyses were conducted according to the revised version of the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statements (17) and are summarized in Figure 1. With the patients' consent, each family caregiver was contacted to explain the purpose and procedures of the study and to request their participation. An independent assessor (a trained research assistant) undertook measurements one week before the intervention (time 1), one week after the intervention (time 2), and one year after the intervention (time 3) by using a set of questionnaires.

Measures

At times 1, 2, and 3, the study participants completed two scales: the Family Support Services Index (FSSI) and the Specific Level of Functioning Scale (SLOF). The average number and duration of patients' rehospitalizations were recorded over the six months before the intervention (time 1), over the six-month period of intervention (time 2), and at 12 months after the intervention (time 3). All figures were obtained from the outpatient clinic record systems. Demographic characteristics of the patients and their families, such as age, gender, educational level, and duration of mental illness, were recorded at baseline. Use of antipsychotic medication was noted from the patients' outpatient treatment sheets over time, and dosages were converted into haloperidol equivalents for comparison purposes (18). Five items of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (19) were used to assess severity of positive symptoms at baseline and posttest.

The SLOF (20) is a 43-item assessment scale on which each item is rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, totally dependent, to 5, highly self-sufficient, along three functional areas pertaining to patients with schizophrenia: self-maintenance, social functioning, and community living skills. The Chinese version of the scale (21) used in this study demonstrated satisfactory content validity, test-retest reliability (r=.76), and internal consistency (alpha=.88 to .96 for subscales) for Chinese patients with schizophrenia. The Chinese versions of the BPRS and the SLOF also demonstrated high item equivalence with the original English version (15). The 16-item FSSI (22) is a checklist of items with yes-or-no responses that measures mental health service needs and use by families of patients with mental illness. The Chinese version demonstrated satisfactory interrater reliability (r=.88) and internal consistency (alpha=.84) (15). Responses to the service use items were checked against the outpatient records by the principal researcher, and a high correlation between the two was noted.

Treatment conditions

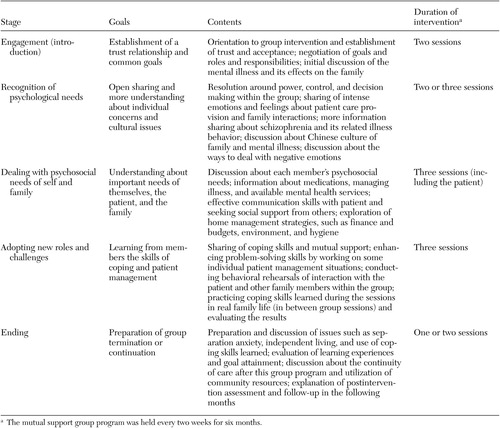

The 32 participants in the mutual support group received a six-month program of mutual support as well as routine psychiatric outpatient care. The group met every two weeks for 12 sessions, each lasting two hours. A peer leader, elected by group members and trained by researchers during a two-day leadership workshop, worked closely with a group facilitator (principal researcher), assisting and encouraging the development of the group in stages, as recommended in the mutual support literature (23). The major contents of the group sessions in these five stages are summarized in Table 1. Emphasis was given to specific Chinese cultural characteristics and issues, including a strong social stigma associated with mental illness and seeking mental health services, a hierarchical but interdependent family structure, and a strong tendency to expect immediate and practical help (14,23,24). Time was given to individual problem solving and to helping individual members deal with particular troubles. Postmeeting practice in caring for the mentally ill relative at home was also emphasized and evaluated after each group stage.

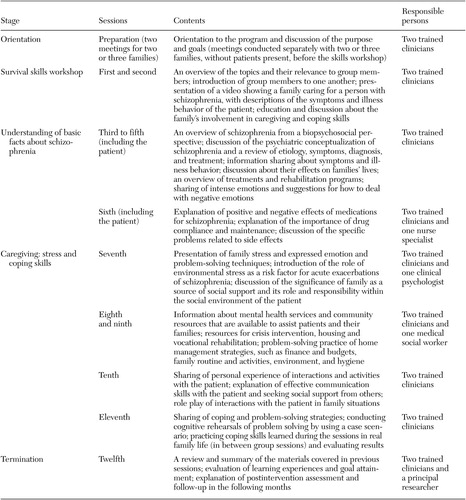

Similarly, the 33 participants in the psychoeducation group received 12 biweekly, two-hour family education and support sessions conducted by the two clinicians as well as routine outpatient care. The two clinicians were psychiatric nurses who were selected by the clinics and were experienced in leading group and psychiatric rehabilitation programs. They were trained by the research team and one family therapist via two three-day workshops and practice within five family sessions, which were rated and evaluated by the training team. The content and format of the psychoeducation program were similar to those used by McFarlane and associates (25). The duration of the education and survival skills sessions was modified to six months in accordance with participants' preferences and convenience and given the resource constraint. The purposes of this intervention were to provide information about schizophrenia and its treatment, develop social support networks and coping skills, and provide techniques for improving communication, problem solving, and crisis intervention. The content of the program is summarized in Table 2 in five stages.

In both the mutual support and psychoeducation interventions, patients were invited to attend three sessions, which focused on knowledge of the illness and its treatment, drug compliance, and available mental health services. Seven experts in psychiatric rehabilitation (psychiatrists, psychologists, and nurse specialists) independently rated the appropriateness of the contents of the two programs, and revisions were made to enhance content validity. Supervision and progress monitoring of the two programs included consistent reviews of the audiotape of each session and regular clarification of problems and issues arising from the meetings.

The 31 participants in the standard care group received routine psychiatric outpatient and family services only, consisting of monthly medical consultation and advice, individual nursing advice on community health care services, social welfare and financial services provided by medical social workers, and counseling provided by clinical psychologists if necessary.

Data analysis

The data analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis that maintained the advantages of random allocation that might otherwise have been lost if participants were excluded from the analysis because they withdrew from the study or failed to comply with treatment (26). Pre- and posttest scores and demographic data were analyzed by using SPSS for Windows version 11.0. Demographic differences between the three groups were assessed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test by ranks (H statistic), as appropriate. Multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) (3 × 3) were performed for the dependent variables to determine whether treatment was associated with the interactive effects postulated (group × time). Post-hoc analysis using Tukey's honestly significant difference test for multiple comparisons was performed for measures for which results were significant in the MANOVA (27). The level of significance for the statistical tests was set at .05.

Results

Sample characteristics

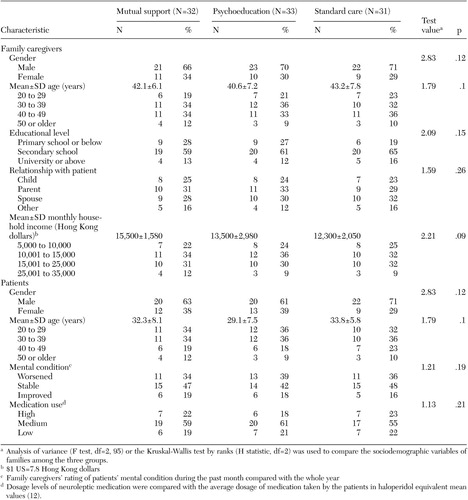

Table 3 summarizes the family caregivers' and patients' sociodemographic characteristics. Among the participants in all three groups, more than two-thirds of family caregivers (21 to 23 caregivers) were men. Participants' mean±SD age was 40.6±7.2 to 43.2±7.8 years (range, 22 to 60 years). Participants' relationship with the patient was mainly parent, spouse, or child.

About two-thirds of the patients were men. Patients' mean age was 37.3±5.8 to 28.8±7.5 years (range, 20 to 49 years). More than half of them (17 to 20 in each group) were taking a medium dosage of antipsychotics (haloperidol equivalent mean values [12] of between 8.30±7.02 and 10.34±8.13 mg/day). Two-thirds of the patients (21 to 23 patients, or 66 to 70 percent) in the three groups were taking oral medication, and one-fifth (six or seven patients, or 19 to 23 percent) were taking both oral and depot intramuscular medications. Nearly half the patients in the three groups were taking atypical neuroleptics (14 to 16 patients, or 45 to 49 percent). The mean duration of illness was just over two years (six months to five years).

Twenty-eight participants (88 percent) from the support group and 31 (94 percent) from the psychoeducation group completed the intervention. These participants, together with those who dropped out or were absent for more than four group sessions—five in the mutual support group (16 percent), two in the psychoeducation group (6 percent), and one in the standard care group (3 percent)—were evaluated at three outcome measurement points (Figure 1). Reasons for discontinuing treatment were similar for the two interventions, including insufficient time to attend (three participants, or 5 percent), worsening of the patient's mental state (three participants, or 5 percent), the caregiver's being the only person taking care of the patient (two participants, or 3 percent), and lack of interest (two participants, or 3 percent).

As can be seen in Table 3, no significant differences were found in any of the demographic variables among the three groups. Nor were any significant correlations (r<.30) found between the demographic variables and patient and family measures at baseline.

Treatment effects

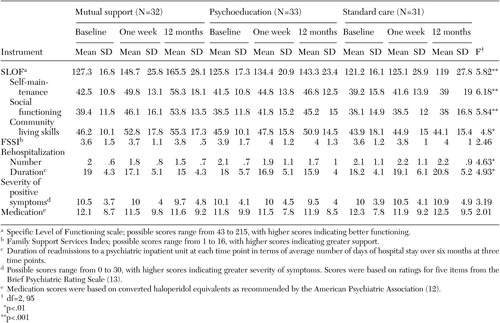

A between-groups comparison of the baseline (time 1) scores of dependent variables based on the ANOVA test indicated no significant differences between the three groups. A statistically significant difference was found between the three groups on the combined dependent variables (F=4.89, df=5, 190, p=.005; Wilks' lambda=.98; a large effect with partial eta squared=.18). The results of the MANOVAs for the dependent variables in the repeated-measures analysis when considered separately (Table 4) indicated statistically significant differences between the three groups on an improvement in the patients' SLOF score and a reduction in the duration and number of patients' rehospitalizations. The SLOF subscale scores also indicated statistically significant differences between the three groups on all subscales. The intergroup mean differences exceeding the minimum significant differences for Tukey's procedure were indicated in the patients' psychosocial functioning and the number and duration of rehospitalizations of the support group, which improved significantly over the period from time 1 to time 3 compared with the other two groups. For the standard care group, the SLOF score showed a marked deterioration at time 3 and the incidence and duration of rehospitalizations consistently increased at time 2 and time 3. However, the high frequency of rehospitalizations (about two in six months) might have been related to the fact that the patients with relatively new diagnoses were frequently hospitalized for short durations (five to seven days) for observation and adjustment of the treatment regimen as well as to the fact that the families were getting better at identifying prodromal symptoms that indicated an impending relapse (25).

As can be seen from Table 4, neuroleptic medication scores changed slightly over time and thus did not differ between the three groups. The FSSI scores in the three groups (mean of 3.6 to 4) were also stable between baseline and 12-month follow-up, indicating no significant change in demand for services over time. The most frequently requested services included day programs for patients (for example, occupational training and recreational activities), patient counseling, home visits by community psychiatric nurses, and respite care. Even though the patients' symptom scores were slightly lower in the mutual support and psychoeducation groups posttest, no significant differences in these symptom scores were noted between the three groups over time.

Discussion

Recent studies suggest that community-based family interventions for persons with schizophrenia or other serious mental illnesses are effective and efficient (3,4). However, few experimental studies have been undertaken of the effectiveness of this type of intervention as an adjunct to routine clinical care within the community mental health service system. The overall results for the six-month family support group intervention for schizophrenia reported here are encouraging and positive. The participants in the support group reported greater improvement in all three aspects of the patients' level of functioning, including self-maintenance, social functioning, and community living skills, as well as a significant reduction of patient rehospitalizations compared with the psychoeducation and standard care groups. This finding indicates the importance of peer support and empowerment among the families who, within a mutual support group, are able to feel themselves "all in the same boat" with fellow sufferers (2,11). This model of family intervention was provided in a flexible, interactive, and peer-led manner and therefore might be more feasible for community mental health services, where there are resource constraints and a requirement to match treatment models to family needs.

Recent studies in Western and Asian populations also indicate that when family caregivers are able to participate in a support group, this participation is associated with improvements in their psychological adjustment, both in their ability to cope and in their caregiving role, and, consequently, in an amelioration in patients' physical and mental conditions (2,28). More than a decade ago, Medvene and Krauss (29) reported that family participation in support groups for persons with mental illness improved the family members' initiative and enabled them to feel comfortable talking freely with other participants about their psychosocial problems in caregiving. A review of the audiotapes of the support group sessions revealed that the participants used active and interactive help-seeking coping strategies, such as further exploration of the problems encountered and discussions about ways of coping with caregiving. These coping strategies may increase family members' knowledge about the illness and about care provision.

As in the studies of clinical efficacy of some family psychoeducation and behavioral programs for schizophrenia, the mutual support group in this study was associated with positive effects on the duration and number of rehospitalizations and psychosocial functioning of patients with schizophrenia, but without a corresponding increase in the use of outpatient services. These findings are consistent with those of studies among patients with other mental illnesses (8,11), in which it was found that greater financial resources of families participating in family support groups, relative to routine care, may be due largely to shorter hospital stays and more appropriate use of services.

In contrast with the suggestion that family intervention should be of at least nine months' duration and conducted at home (12), the mutual support used in this study provides a flexible client-led group environment with only a six-month intervention, yet it still demonstrated a significant positive effect on patients' functioning and readmission compared with both standard individual care and multiple-family education. Indeed, as with single-family interventions, emphasis and time spent on the families' problem solving, effective coping, and patient management in a timely and accurate fashion is also feasible in this multiple-family support group (25,30).

It is interesting that the attrition rates in all three groups were very low. The high group attendance rate may be explained by the fact that in this sample the illness was of short duration and the families may thus have been more optimistic and motivated about the potential for change (3,6). Thus there is a need for family services to offer accessible and early intervention when planning patients' discharge. Research on support groups also suggests the importance of understanding the helpful environment within and outside a support group and the need to emphasize the exploration of its therapeutic ingredients (31). However, the difference in attrition and nonattendance between the two interventions (15.6 percent compared with 6.1 percent) favoring the psychoeducation group is worthy of exploration in follow-up study with larger samples.

Despite the fact that study participants were randomly selected, most of the families in this study were volunteers and highly motivated to participate in the group interventions—that is, very low dropout rates were reported—with an education level of secondary school or above. As in studies in the United States (8,13,32), a relatively small number of families in the outpatient services could participate in this study. Consistent with the explanation for the attrition rates, the reasons of nonparticipation included lack of interest, worsening of the patient's mental state, and the caregiver's being the only person taking care of patient. Thus this sample may not be representative of those receiving psychiatric treatment.

In contrast to the characteristics of samples in studies conducted in the United States and other Western countries, most of the family caregivers in this study were men and were the parent, spouse, or child of the patient. These culturally specific characteristics of Chinese family caregivers have been found in the extended family structure in Hong Kong, in which strong kinship, interdependence, and filial responsibility are found among family members and between generations (23,24). Male spouses, parents, and children are more receptive to taking on the caregiver role in Chinese families.

All the patients in this study were recruited from psychiatric outpatient clinics and had a duration of illness of no more than five years—that is, less chronic illness. The findings of the study cannot be generalized to Chinese patients who have a longer duration of illness, which is considered to present a very different caregiving experience in terms of the patient's symptoms and behaviors. Professional input or self-administration of group members has been found to serve as a booster and to be important in maintaining the effects of a mutual support group intervention for group participants (32).

Finally, although the group interventions in this study were of shorter duration (less than nine months), as was the follow-up period, and attrition rates were lower, these factors might influence the effectiveness of the interventions, particularly the psychoeducation group, which often becomes substantial and more prominent over a lengthy follow-up period (8). It is recommended that a longer follow-up period be used in order to understand the long-term effects of the two interventions.

Conclusions

The family support group program for schizophrenia tested in this study demonstrated a positive effect on patients' functioning and rehospitalizations compared with the psychoeducation intervention and compared with routine care. This controlled trial may have implications for the dissemination of effective family interventions, given its emphasis on the importance of peer support for patients with schizophrenia. The study findings warrant further empirical investigation of the mutual support group model originated in the West, preferably with families from different socioeconomic backgrounds and in patient populations with co-occurrence of other mental health problems.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 216020 from the Health Care and Promotion Fund, Hospital Authority Hong Kong.

The authors are affiliated with the Nethersole School of Nursing in the Faculty of Medicine of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, 7/F Esther Lee Building, Shatin, Northern Territories, Hong Kong (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of a clinical trial comparing family mutual support, psychoeducation, and standard care groupsa

a FSSI, Family Support Service Index; SLOF, Specific Level of Functioning Scale

|

Table 1. Characteristics of a mutual support group intervention for family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia

|

Table 2. Characteristics of the psychoeducational group program for family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia

|

Table 3. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of family caregivers and persons with schizophrenia receiving mutual support, psychoeducation,or standard care (N=96)

|

Table 4. Dependent variable scores at times 1, 2, and 3 and results of multivariate analysis of variance (group × time) for three groupsof family members of patients with schizophrenia

1. Annual Report 2002–03. Hong Kong SAR, China, Hospital Authority Hong Kong, 2004Google Scholar

2. Heller T, Roccoforte JA, Hsieh K, et al: Benefits of support groups for families of adults with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:187–198, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Pharoah FM, Mari JJ, Streiner D: Family intervention for schizophrenia, in Cochrane Systematic Reviews, Issue 3, 2001. Oxford, The Cochrane Library, 2001Google Scholar

4. Barbato A, D'Avanzo B: Family interventions in schizophrenia and related disorders: a critical review of clinical trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 102:81–97, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Xiong MG, Ran MS, Li SG: A controlled evaluation of psychoeducational family intervention in a rural Chinese community. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:239–247, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Zhang M, Wang M, Li J, et al: Randomized controlled trial of family intervention for 78 first-episode male schizophrenia patients: an 18-month study in Suzhou, Jiangsu. British Journal of Psychiatry 165(suppl 24):96–102, 1994Google Scholar

7. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: At issue: translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–9, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903–910, 2001Link, Google Scholar

9. Telles C, Karno M, Mintz J, et al: Immigrant families coping with schizophrenia. Behavioral family intervention vs case management with a low-income Spanish-speaking population. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:473–479, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gournay K: Mental health nurses working purposefully with people with serious and enduring mental illness: an international perspective. International Journal of Nursing Studies 32:341–352, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Citron M, Solomon P, Draine J: Self-help groups for families of persons with mental illness: perceived benefits of helpfulness. Community Mental Health Journal 35:15–30, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Mueser KT, Sengupta A, Schooler NR, et al: Family treatment and medication dosage reduction in schizophrenia: effects on patient social functioning, family attitudes, and burden. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69:3–12, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Norton S, Wandersman A, Goldman CR: Perceived costs and benefits of membership in a self-help group: comparisons of members and nonmembers of the Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Community Mental Health Journal 29:143–160, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Fung C, Ma A: Family management in schizophrenia. Hong Kong Journal of Mental Health 26:53–63, 1997Google Scholar

15. Chien WT: Educational Needs of Families Caring for Patients with Schizophrenia. Hong Kong, Faculty of Medicine, Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2001Google Scholar

16. Annual Report 2000–01. Hong Kong SAR, China, Hospital Authority Hong Kong, 2001Google Scholar

17. Altman DG, Schultz KF, Moher D: The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine 134:663–694, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Bezchlibnyk-Butler KZ, Jeffries JJ (eds): Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs, 8th ed. Seattle, Hogrefe and Huber, 1998Google Scholar

19. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychiatric Reports 10:799–812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Schneider LC, Struening EL: SLOF: a behavioral rating scale for assessing the mentally ill. Social Work Research and Abstracts 19:9–21, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Lee KL: Study on the Effect of the Pre-Discharge Rehabilitation Program on the Level of Functioning of Chronic Schizophrenic Patients in Hong Kong. Hong Kong SAR, China, Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1999Google Scholar

22. Heller T, Factor A: Permanency planning for adults with mental retardation living with family caregivers. American Journal on Mental Retardation 96:163–176, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

23. Bae SW, Kung WWM: Family intervention for Asian Americans with a schizophrenic patient in the family. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:532–541, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Meredith WH, Abbott DA, Tsai R, et al: Healthy family functioning in Chinese cultures: an exploratory study using the Circumplex Model. International Journal of Sociology and Family 24:147–157, 1994Google Scholar

25. McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, et al: Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679–687, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Bailer JC, Mosteller F (eds): Medical Uses of Statistics, 2nd ed. Boston, Mass, NEJM Books, 1992Google Scholar

27. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed. Boston, Allyn and Bacon, 2001Google Scholar

28. Pearson V, Ning SP: Family care in schizophrenia: an undervalued resource, in Social Work Intervention in Health Care: The Hong Kong Scene. Edited by Chan CLW, Rhind N. Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 1997Google Scholar

29. Medvene L, Krauss DH: Causal attributions and parent-child relationships in a self-help group for families of the mentally ill. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 19:1413–1430, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Dyck DG, Hendryx MS, Short RA, et al: Service use among patients with schizophrenia in psychoeducational multiple-family group treatment. Psychiatric Services 53:749–754, 2002Link, Google Scholar

31. Maton KI: Moving beyond the individual level of analysis in mutual help groups research: an ecological paradigm. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 29:272–286, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233–238, 1999Link, Google Scholar