Treatment of Tobacco Use in an Inpatient Psychiatric Setting

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Despite high rates of tobacco use among psychiatric patients, such patients are one of the least studied groups of smokers, and little is known about their access to cessation treatment. This study examined delivery of tobacco cessation services in a smoke-free inpatient psychiatric setting. METHODS: Medical records of 250 psychiatric inpatients who were admitted from 1998 to 2001 were randomly selected and systematically reviewed. RESULTS: A total of 105 patients (42 percent) were identified as current smokers; the mean±SD number of cigarettes that they smoked per day was 21±15. Smokers evidenced statistically greater agitation and irritability compared with nonsmokers. None of the smokers received a diagnosis of nicotine dependence or withdrawal, and smoking status was not included in treatment planning for any patient. Nicotine replacement therapy was prescribed for 59 smokers (56 percent); of these patients, 54 (92 percent) used it. Smokers who were not given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy were more than twice as likely as nonsmokers and smokers who were given a prescription for this therapy to be discharged from the hospital against medical advice. Only one smoker was encouraged to quit smoking, referred for cessation treatment, or provided with nicotine replacement therapy on discharge. CONCLUSIONS: Psychiatric inpatients smoke at high rates, yet interventions to treat this deadly addiction are rare. Furthermore, nicotine withdrawal left unaddressed may compromise psychiatric care.

Nationally, smoking was banned in all hospitals, including psychiatric inpatient units, in 1992 (1). The smoke-free policy was designed to minimize secondhand smoke exposure among patients, visitors, and staff; encourage smoking cessation; and serve as an example to the community. The policy requires smokers who are hospitalized to abstain temporarily from tobacco. For some patients, hospitalization may provide one of the few experiences with not smoking for an extended period. A review of 22 studies examined the impact of total or partial smoking bans in psychiatric inpatient units and concluded that while the policies resulted in few behavioral consequences, they seemed to have little or no effect on cessation (2). The authors identified smoking cessation strategies as an essential component of smoking ban polices. When smoking was allowed openly on psychiatric units, records of nursing staff time revealed that an average of 15 minutes was spent per shift managing patients' cigarette use (3). Ideally, a portion of the time saved with a no smoking policy could be shifted to deliver cessation services.

The U.S. Public Health Service recommends that all patients be screened for tobacco use, advised to quit, and offered intervention (4). The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (5) recommends that hospitalized smokers be provided with all effective cessation treatments, including nicotine replacement therapy when appropriate. The goals of nicotine replacement therapy are to reduce discomfort, maximize compliance with a hospital's no smoking policy, and minimize some of the undesirable adrenergic effects that are associated with nicotine withdrawal. For smokers with comorbid psychiatric conditions, the AHRQ recommends offering cessation treatments that have been shown to be effective in the general population, including skill training, pharmacotherapy, and clinical support (5). Given the complicated relationship between mental illness and smoking, integration of cessation efforts into psychiatric care is recommended (6,7,8). The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recommends that psychiatrists assess the smoking status of all patients, including readiness to quit, level of nicotine dependence, and previous quitting history (6). Clinicians are encouraged to use this information to provide explicit advice to motivate patients to stop smoking. Additionally, management of nicotine withdrawal is identified as a goal in and of itself, especially for patients who are hospitalized on smoke-free wards.

An extensive body of literature has documented the effectiveness of behavioral and pharmacologic treatments that are delivered in inpatient hospital settings (9). However, psychiatric patients have been largely excluded from these trials. Smoking rates among psychiatric patients tend to be two to four times the rate for the general population (10). Psychiatric patients also are more likely to be heavy smokers. As a group, individuals with psychiatric disorders are estimated to account for 44 percent of the U.S. tobacco market (11), yet they are among the least studied in clinical trials.

Persons with mental illness have been identified as a priority population for research aimed at eliminating tobacco-related health disparities. Research needs include the study of health care systems for the delivery of nicotine dependence treatment and methods for improving treatment access (4,6,12,13,14). Our study examined rates of smoking among psychiatric inpatients, explored evidence of nicotine withdrawal on a smoke-free inpatient psychiatric unit, examined treatment of tobacco dependence in the inpatient psychiatric setting, and identified treatment practices that might be targeted to improve outcomes among psychiatric inpatients who smoke.

Methods

Setting and participants

The sample was drawn from an adult inpatient psychiatric service in a teaching hospital in San Francisco. The 22-bed acute psychiatric service followed a biopsychosocial approach in the treatment of adults aged 18 years and older with severe behavioral and emotional disturbances. Patient evaluation, treatment planning, and treatment delivery were conducted by multidisciplinary teams. In 1988 the hospital instituted a 100 percent smoke-free policy. Charts of patients who were admitted to the unit from November 1998—when patient smoking status was added to the inpatient intake form—to December 2001 were randomly selected. During this time frame, 2,053 patients were admitted to the unit. By using a computerized random sampling program, 250 charts were selected for our study. Six of these charts were excluded: three charts could not be located, two charts had information on patients who were part of a previous research protocol, and one chart had information on a patient who was treated by one of the study investigators. Six additional charts were randomly selected to form a final sample of 250. For charts that indicated multiple hospitalizations, only the most recent admission was reviewed.

Measures

A codebook and systematic coding form were created to gather data from the medical records. Data collected included admission date and commitment status, demographic information, smoking status, alcohol and drug use history, medications prescribed during the hospitalization, DSM-IV diagnoses on discharge, and discharge status. Smoking status was reported as current or none; the number of packs per day and years of smoking were recorded if this information was available. Patients with missing data on smoking status who presented to the unit with smoking paraphernalia, requested cigarettes, or were caught smoking on the unit were coded as current smokers. All charts were reviewed for documentation of the presence of DSM-IV nicotine withdrawal symptoms, which may have been reported by patients or observed by staff. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms include dysphoric or depressed mood; insomnia; irritability, frustration, or anger; anxiety; difficulty concentrating; restlessness; and increased appetite or weight gain (15). DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for nicotine withdrawal require the presence of four or more of these withdrawal symptoms after the abrupt cessation of nicotine. For current smokers, inclusion of smoking status in the master treatment plan, prescription of nicotine replacement therapy or bupropion, and discharge advice and referrals were coded. Presence of cigarette craving was also recorded, operationalized as patients' requests for cigarettes or complaints of urges to smoke. The mean±SD time required for chart review was 25±10 minutes per chart and was highly correlated with the patients' length of stay (r=.71).

Procedures

The study collected data by medical chart review. No contact with patients was required. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco. Chart data were anticipated to be fairly complete, because medical records staff were known to audit approximately 93 percent of the inpatient charts. A research assistant, blinded to the study's hypotheses, reviewed the sampled charts. The first ten charts that were coded underwent a second review to ensure understanding of and adherence to the codebook. To examine interrater reliability, a second reviewer randomly selected and independently verified 25 of the records (10 percent). Overall agreement was 96 percent, with 93 percent agreement for the coding of nicotine withdrawal symptoms (intraclass correlation=.84). Concurrent validity of the chart review method for assessing nicotine withdrawal symptoms was evaluated in a separate sample of 77 smokers on a smoke-free inpatient psychiatric unit and found to correlate significantly (r= .52, p=.001) with patient self-report on the nicotine withdrawal scale of Shiffman and colleagues (16).

Analyses

Analyses were conducted by using SPSS version 11.0.1. Descriptive statistics were conducted to characterize the sample and to examine rates of cigarette smoking and treatment services. Chi square statistics and an analysis of variance analysis (ANOVA) tested for differences in smoking rates by patient factors. Logistic regression and an ANOVA were conducted to examine differences in withdrawal symptoms and treatment outcomes by smoking status and prescription status of nicotine replacement therapy, with identified group differences controlled for.

Results

Descriptive characteristics

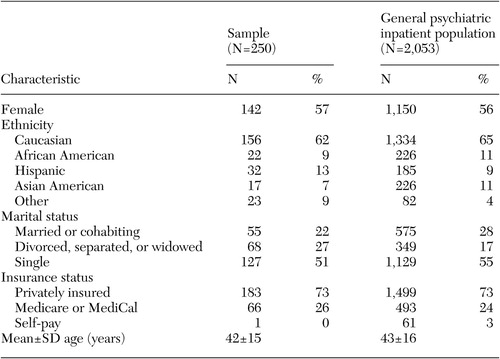

As Table 1 shows, the study sample was compared with the larger patient pool; this comparison suggested that the sample was representative. In our sample, 81 patients (32 percent) were employed. DSM-IV psychiatric disorders on discharge were depressive disorder (105 patients, or 42 percent), psychotic disorder (66 patients, or 26 percent), substance use disorder (55 patients, or 22 percent), bipolar disorder (47 patients, or 19 percent), anxiety disorder (25 patients, or 10 percent), and other axis I disorders (34 patients, or 14 percent). Sixty-three patients (25 percent) had more than one axis I disorder, and 38 (15 percent) had an identified axis II personality disorder or traits. Forty-one admissions (16 percent) were voluntary; 159 (64 percent) were hospitalizations for danger to self. Patients had a mean of 1.4±1.3 previous hospitalizations on the unit (range, 0 to 15).

Smoking status

Sixteen charts (6 percent) were missing information on smoking status, and these charts were excluded from further analyses. Of the remaining 234 patients, 105 (45 percent) were identified as current smokers. Smoking prevalence did not differ significantly by year of admission. The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day—recorded in 85 of the 105 charts for identified smokers—was 1.1±.7 packs, ranging from a few cigarettes a week to 4.5 packs daily. Smoking duration—recorded for 65 current smokers—averaged 14.6± 10.9 years.

Smoking status and patient factors

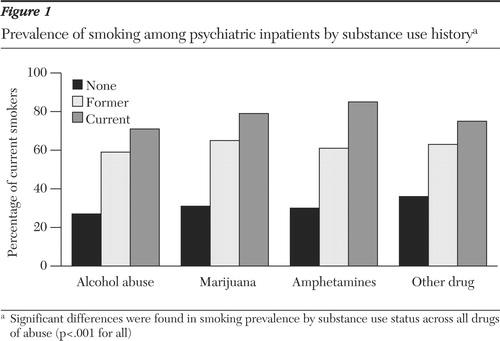

No significant differences were found in smoking rate by gender, race or ethnicity, insurance status, or employment status. Significant differences were found for age, marital status, psychiatric diagnosis, and substance use history. Rates of smoking decreased precipitously with increasing age, F=17.64, df=1, 233, p<.001. Rates of smoking were highest among single patients compared with divorced or married patients (χ2=6.02, df=2, p=.049). Patients with bipolar disorder (odds ratio [OR]=2.2, p=.023) or a substance use disorder (OR=5.3, p<.001) were more likely than patients with other diagnoses to smoke cigarettes. As Figure 1 shows, rates of smoking were consistently associated with substance use history across all drug types, with current users having rates of smoking that exceeded 70 percent.

Withdrawal symptoms by smoking status

The mean number of symptoms charted was 4.2±1.3 for current smokers and 3.8±1.4 for nonsmokers. Documentation of withdrawal symptoms increased linearly with length of stay (r=.32, p<.001), perhaps because of an extended window of observation. When length of stay was controlled for, smoking status significantly predicted the number of withdrawal symptoms observed (F=7.11, df=1, 234, p=.008). Smoking status remained significant (p=.025) when the analysis controlled for identified group differences of bipolar diagnosis, current substance use, age, and marital status. Among smokers, presence of a substance use disorder did not predict the number of withdrawal symptoms observed.

The individual withdrawal symptoms were examined by smoking status. Compared with nonsmokers, current smokers had significantly higher rates of irritability (75 smokers, or 71 percent, compared with 71 nonsmokers, or 55 percent) and agitation (69 smokers, or 66 percent, compared with 63 nonsmokers, or 49 percent) and were more likely to have four or more of the DSM-IV symptoms of withdrawal (78 smokers, or 74 percent, compared with 74 nonsmokers, or 57 percent) (p<.05 for all). Cigarette craving was documented for 42 smokers (40 percent). None of the charts listed a diagnosis of nicotine dependence or withdrawal, and none included smoking status in the master treatment plan.

Smoking cessation treatments

Charts of current smokers were reviewed for the delivery of smoking cessation treatments. Fifty-nine smokers (56 percent) were given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy: 26 (25 percent) were given a prescription for a nicotine patch, 24 (23 percent) were given a prescription for nicotine gum, and nine (9 percent) were given a prescription for both forms of nicotine replacement therapy. Seven smokers (7 percent) were given a prescription for bupropion; however, their charts did not indicate that it was prescribed for smoking cessation. Smokers who were given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy were heavier smokers (mean number of 26±16 cigarettes smoked per day) than smokers who were not given a prescription for this therapy (mean number of 16±12 cigarettes smoked per day; p<.01) and were more likely to be identified as craving cigarettes than smokers who were not given a prescription for this therapy (OR=13.8, p<.001). Prescription rates of nicotine replacement therapy did not differ by patients' demographic, psychiatric, or substance use characteristics, length of stay, or year of admission. Nicotine replacement therapy was used by 54 of the 59 patients for whom it was prescribed (92 percent). Patients who used this therapy used it for an average of 78 percent of their hospital stay. Chart review indicated that nicotine replacement therapy was sometimes delayed, interrupted, or discontinued.

Two-thirds of prescriptions for the nicotine patch were for the 21 mg dosage, and all the prescriptions for the nicotine gum were for the 2 mg dosage. The mean daily dosage of nicotine replacement therapy was 12±8 mg overall and 22±6, 14±6, and 5±5 mg among patients receiving both forms of nicotine replacement therapy, the patch, and gum, respectively (p<.001). By using the estimate that 1 mg of nicotine equates to one cigarette, we calculated the median nicotine replacement level to be 45 percent, highest among patients who received both forms of nicotine replacement therapy (median of 69 percent) and lowest among those who received gum only (median of 15 percent).

Associations were examined between the prescription of nicotine replacement therapy and patient treatment outcomes. Smokers who were not given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy were more than twice as likely to be discharged from the hospital against medical advice (ten of 46 smokers, or 22 percent) as nonsmokers (ten of 129 nonsmokers, or 8 percent) and smokers who were given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy (six of 59 smokers, or 10 percent) (χ2=6.79, df=2, p=.034). The association remained significant (p=.05) in a logistic regression that controlled for patients' age, marital status, substance use, and diagnosis of bipolar disorder. A trend was seen for higher rates of lorazepam prescription and use of seclusion among smokers who were not given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy compared with nonsmokers and smokers who were given a prescription for this therapy, although the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Discharge planning and referrals

Charts of current smokers were reviewed to determine the frequency that clinical staff advised the patient to quit smoking as well as the frequency of referrals for cessation services after discharge. Only one smoker (1 percent) was advised to quit smoking, referred for smoking cessation counseling, or provided with nicotine replacement therapy on discharge. Two smokers (2 percent) were given a prescription for bupropion on discharge; however, their charts did not indicate that this prescription was for smoking cessation.

Discussion

The smoking rate in this inpatient sample was 1.6 times as great as that reported in an earlier study that was conducted from 1998 to 1999 with outpatients who were recruited from the same hospital (17) and 2.6 times as great as surveillance data on adults in California (18). Smoking rates in our sample were highest among patients who were younger, were single, were current substance users, and were given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or a substance use disorder. Similarly, in the analysis of data from the National Comorbidity Study by Lasser and colleagues (11), diagnoses of bipolar or substance use disorders in the past month were associated with the highest rates of tobacco use relative to other psychiatric diagnoses.

Documentation of symptoms characteristic of nicotine withdrawal was significantly greater among smokers compared with nonsmokers, and smokers were more likely to meet the DSM-IV criteria of four or more symptoms. Smoking status remained a significant predictor of withdrawal symptoms after controlling for group differences, including current drug or alcohol use. Furthermore, the presence of a substance use disorder among smokers was unrelated to the number of nicotine withdrawal symptoms that were observed. The two withdrawal symptoms that were significantly more prevalent among smokers—irritability and agitation—are symptoms that are most likely to cause disruption on a psychiatric unit. If interventions can be implemented to manage these symptoms effectively, treatment outcomes will likely be improved.

Just over half the current smokers were given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy, and nearly all these patients used the therapy for most of their hospital stay, which suggests that patients use nicotine replacement therapy when it is prescribed. This finding is far more hopeful than previous case reports from inpatient psychiatric units that suggested that nicotine replacement therapy was helpful for few patients and was often rejected or discontinued (19,20). In our study, patients who were given a prescription for nicotine replacement therapy received just under half the nicotine level they received when they were smoking, thus these patients may also experience withdrawal symptoms. Patients who were given a prescription for two modalities of nicotine replacement therapy were closer to their typical intakes. However, many charts were missing data on smoking rate, making the dosing of nicotine replacement therapy difficult to calculate.

A twofold difference was observed in rates of discharge against medical advice by prescription status of nicotine replacement therapy; smokers who were not given a prescription for this therapy were more likely to leave the hospital with unmet psychiatric needs. Studies conducted at the time psychiatric hospitals instituted a smoke-free policy suggested that staff fears of increased rates of assaultive behavior by patients and discharges against medical advice were unfounded (3,21,22,23). Other studies noted severe difficulties among some patients (19). Our study identified differences in patient outcomes based on the prescription of nicotine replacement therapy. Notably, smokers who were given a prescription for this therapy had outcomes that were similar to those of nonsmokers. These findings suggest that the prescription of nicotine replacement therapy may be a simple intervention with clinically significant implications. Our data are observational, and causation cannot be determined. Randomized trials are needed. However, a wealth of literature from hospital-based cessation trials with general medicine patients supports nicotine replacement therapy as a mechanism by which outcomes can be improved (9).

As recommended in the APA guidelines for nicotine dependence treatment, the hospital unit was 100 percent smoke free, a majority of patients were asked about their smoking practices, and just over half the patients who smoked were given prescriptions for nicotine replacement therapy (6). The APA treatment guidelines suggest the use of nicotine replacement therapy in inpatient settings only when patients complain of withdrawal symptoms or if withdrawal symptoms are observed (6). However, patients and clinical staff are likely to have difficulty deciphering whether these symptoms are caused by smoking cessation or other psychogenic factors. Notably, a majority of nonsmokers were observed to have four or more of the DSM-IV symptoms, demonstrating the lack of specificity of nicotine withdrawal. Assuming no medical contraindications exist (for example, pregnancy), our study provides evidence to support the prescription of nicotine replacement therapy to all smokers on admission, consistent with the AHRQ guidelines for hospitalized smokers (5).

Areas to be targeted for systems improvement include diagnosis and treatment planning, on-unit smoking cessation counseling, and postdischarge referrals for nicotine dependence treatment. We reviewed the charts of 105 smokers; however, none documented patients' readiness to quit, none listed a diagnosis of nicotine withdrawal or dependence, and none included smoking status in the master treatment plan. Nicotine dependence is the most prevalent substance use disorder among adult psychiatric patients, and it needs to be placed on the radar of psychiatric practice (10). Only one chart (1 percent) contained documentation that the patient was advised to quit smoking, was referred to a cessation program, or was provided with nicotine replacement therapy on discharge. Without follow-up, patients who are smokers are certain to return to smoking once they leave the hospital. An observational study found that of 39 smokers who were given nicotine gum while on a smoke-free psychiatric unit, 80 percent resumed smoking immediately after discharge and another 10 percent resumed smoking within two months after discharge (24). The patients who reported continued abstinence were lighter smokers on admission. The authors concluded that if the goal of smoke-free units is to encourage cessation, then more structured programs will be required, particularly for heavier smokers. Research on hospitalized general medicine patients has identified optimal treatment as structured behavioral support combined with nicotine replacement therapy or bupropion over multiple contacts (25). Psychiatry has the tools and skills to help patients quit this deadly addiction, but it must first recognize smoking as a clinical priority.

Our study was limited by the form of data collection and its restriction to one clinical site. In assessing nicotine withdrawal, our chart review study coded only for the presence of symptoms. Future studies should include measures of symptom severity and duration that are assessed with patients directly. The generalizability of the findings beyond the study site is unknown. Smoking rates are likely to be higher among public health sector patient populations in county and state psychiatric hospitals. In terms of clinical services provided, the site is a nationally recognized psychiatric hospital and teaching center that is located in a state that continues to be aggressive in the war against tobacco. Furthermore, the hospital was one of the first in the nation to go 100 percent smoke free, establishing its policy in 1988, four years before the national mandate (1). In contrast, many U.S. hospitals continue to provide smoking passes to psychiatric inpatients for good behavior—the prevailing message is certainly not one of health but one not too far removed from psychiatry's history. It was only a few decades ago that cigarettes, considered to be one of the most effective forms of reinforcement, were provided to psychiatric patients. In fact, some patients' first experience with cigarettes occurred when they were hospitalized.

Conclusions

Although the walls of secondhand smoke in inpatient units have been cleared, many patients remain heavily addicted to nicotine, and the system must work to address their withdrawal and cessation needs. In terms of lives saved, quality of life, and cost efficacy, treating smoking is considered to be the most important activity a clinician can undertake (26). The nation has progressed to a focus on health with restrictions on tobacco and mandates for cessation (27); we cannot continue to allow psychiatry to lag behind.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the San Francisco Treatment Research Center, which is funded by grant P50-DA-09253 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); by grants R01-DA-02538, R01-DA-15732, and T32-DA-07250 from NIDA; and by a postdoctoral fellowship that is funded by grant 11-FT-0013 from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, 401 Parnassus Avenue, TRC 0984, San Francisco, California 94143-0984 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric inpatients by substance use history

a Significant differences were found in smoking prevalence by substance use status across all drugsof abuse (p<.001 for all)

|

Table 1. Comparison of the study sample with the psychiatric inpatient unit's patient population from 1998 to 2001

1. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO): Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill, JCAHO, 1992Google Scholar

2. El-Guebaly N, Cathcart J, Currie S, et al: Public health and therapeutic aspects of smoking bans in mental health and addiction settings. Psychiatric Services 53:1617–1622, 2002Link, Google Scholar

3. Resnick MP, Bosworth EE: A smoke-free psychiatric unit. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:525–527, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

4. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: a US Public Health Service report: the Tobacco Use and Dependence Clinical Practice Guideline Panel, Staff, and Consortium Representatives. JAMA 283:3244–3254, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al: Smoking cessation. Clinical Practice Guideline No 18. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1996Google Scholar

6. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence: American Psychiatric Association. American Journal of Psychiatry 153(suppl 10):1–31, 1996Google Scholar

7. Dalack GW, Glassman AH: A clinical approach to help psychiatric patients with smoking cessation. Psychiatric Quarterly 63:27–39, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hughes JR, Frances RJ: How to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Psychiatric Services 46:435–436, 1995Link, Google Scholar

9. Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Murphy MF, et al: Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews CD001837, 2003Google Scholar

10. Hughes JR: Possible effects of smoke-free inpatient units on psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:109–114, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, et al: Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA 284:2606–2610, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Fagan P, King G, Lawrence D, et al: Eliminating tobacco-related health disparities: directions for future research. American Journal of Public Health 94:211–217, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Tobacco Dependence Among Smokers With Psychiatric Disorders. Edited by Bailey L. Washington, DC, Center for Tobacco Cessation, 2003Google Scholar

14. Subcommittee on Cessation: Preventing 3 Million Premature Deaths: Helping 5 Million Smokers Quit: A National Action Plan for Tobacco Cessation. Edited by Fiore MC. Washington, DC, Interagency Committee on Smoking and Health, 2003Google Scholar

15. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

16. Shiffman S, Dresler CM, Hajek P, et al: Efficacy of a nicotine lozenge for smoking cessation. Archives of Internal Medicine 162:1267–1276, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Acton GS, Prochaska JJ, Kaplan AS, et al: Depression and stages of change for smoking in psychiatric outpatients. Addictive Behaviors 26:621–631, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Prevalence of current cigarette smoking among adults and changes in prevalence of current and some day smoking—United States, 1996–2001. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 52:303–307, 2003Medline, Google Scholar

19. Greeman M, McClellan TA: Negative effects of a smoking ban on an inpatient psychiatry service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:408–412, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

20. Smith CM, Pristach CA, Cartagena M: Obligatory cessation of smoking by psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 50:91–94, 1999Link, Google Scholar

21. Haller E, McNiel DE, Binder RL: Impact of a smoking ban on a locked psychiatric unit. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:329–332, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

22. Taylor NE, Rosenthal RN, Chabus B, et al: The feasibility of smoking bans on psychiatric units. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:36–40, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Thorward SR, Birnbaum S: Effects of a smoking ban on a general hospital psychiatric unit. General Hospital Psychiatry 11:63–67, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Jonas JM, Eagle J: Smoking patterns among patients discharged from a smoke-free inpatient unit. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:636–637, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

25. West R: Helping patients in hospital to quit smoking. Dedicated counselling services are effective—others are not. British Medical Journal 324:64, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Cromwell J, Bartosch WJ, Fiore MC, et al: Cost-effectiveness of the clinical practice recommendations in the AHCPR guideline for smoking cessation: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. JAMA 278:1759–1766, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000Google Scholar