Smoking Cessation Services in U.S. Methadone Maintenance Facilities

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Most patients in drug treatment smoke cigarettes. This study established the prevalence and types of nicotine dependence services offered in methadone and other opioid treatment clinics in the United States. METHODS: A cross-sectional survey was conducted of all outpatient methadone maintenance clinics in the United States. One person in a leadership position from each clinic was surveyed. The 20-minute survey was collected by phone, fax, or mail, according to responder preference. RESULTS: Fifty-nine percent of the clinics (408 of 697 clinics) responded. The sample was very similar to all outpatient methadone maintenance clinics in the United States in size, region, and ownership. In the 30 days before the survey, respondents reported that their clinics provided the following services to at least one patient: 73 percent provided brief advice to quit, 18 percent offered individual or group smoking cessation counseling, and 12 percent prescribed nicotine replacement therapy. However, the services were provided to very few patients. Clinics with written guidelines that required them to address smoking were much more likely to provide services than those without guidelines. Private for-profit clinics were significantly less likely than public or private nonprofit clinics to treat nicotine dependence. Most respondents (77 percent) reported that their staff were interested in receiving training in nicotine dependence treatment, and more than half (56 percent) had at least one staff member ("champion") with a strong interest in treating nicotine dependence. CONCLUSIONS: A vast majority of methadone patients smoke; yet in the 30 days before the survey only one out of three facilities provided counseling to any patients and only one out of ten prescribed nicotine replacement therapy to any patients. A dual strategy of requiring clinics to provide comprehensive nicotine dependence services and training staff to provide these services may provide the incentive and support necessary for the widespread adoption of treatment for nicotine dependence in methadone facilities.

Each year cigarette smoking accounts for more than 400,000 deaths in the United States (1). Among persons with a history of drug addition, those who smoke are more likely to experience disability and premature mortality than those who do not smoke (2,3,4). Approximately 71 percent of all illicit drug users smoke (5), 74 to 100 percent of patients in drug treatment smoke (6,7), and 85 to 98 percent of patients in methadone maintenance smoke (8,9,10,11). Despite these high rates of dependence, morbidity, and mortality, little is known about the extent to which smoking is addressed in drug treatment.

Two state-based studies and one national survey in Canada examined smoking cessation services in drug treatment. A survey of 53 percent of certified substance abuse counselors in Kentucky (254 of 479 counselors) found that 44 percent of the respondents routinely assessed smoking status, 56 percent routinely advised smokers to quit, 19 percent routinely recommended nicotine replacement to smokers, and 54 percent routinely referred smokers to community-based cessation services (12). A survey of 124 professionals in Nebraska who specialize in drug recovery and treatment found that 25 percent of the professionals routinely advised patients to quit smoking (13). Recently, Currie and colleagues (14) surveyed 225 addiction programs across Canada. They administered a brief 18-item survey to one representative from each program over the phone. More than half the programs (54 percent) reported that they offered patients help in quitting smoking; however, few (10 percent) had "formal" smoking cessation services. Most reported that they placed "very little" emphasis on treatment for smoking cessation.

Several factors argue for treating smoking among methadone patients (15). Most of these patients are older than 30 years (16) and may be experiencing the cumulative health consequences of long-term tobacco use or observing them among their peers. These patients have expressed a need for smoking cessation services: three separate surveys of patients in treatment for opioid addiction found that 58 to 80 percent were interested in quitting smoking (8,11,17). Many of these patients become stable, remain in treatment for extended periods, and are eager to address longer-term health issues. Opportunities for treating smoking abound as patients visit programs on a daily or weekly basis and see health professionals at regular intervals. Methadone programs have a strong national network and are subject to federal oversight, which enhances the potential for forming a national policy on treatment and disseminating information on effective treatment methods to providers.

This study sought to understand how cigarette smoking is currently addressed in drug treatment, to establish a baseline of service provision, and to provide data for future policy. To do so we conducted a survey of smoking cessation services offered in methadone and other opioid treatment clinics in the United States. Our aims were to establish the prevalence of nicotine dependence treatment, describe current treatment practices, and identify factors that might facilitate widespread dissemination of nicotine dependence services into methadone and other opioid treatment clinics.

Methods

Participants and setting

We obtained lists of methadone and other opioid treatment clinics in the United States from the Food and Drug Administration and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Outpatient clinics of the Department of Veterans Affairs were included in the trial; inpatient and detoxification-only providers were excluded. The survey of all outpatient maintenance clinics in the United States (N=697) was conducted from October 2001 to May 2002. All were invited by phone to participate. We surveyed one person in a leadership position from each clinic. The institutional review board of the University of Kansas Medical Center approved study procedures.

Procedures and measures

Interviewers from the survey research center of the University of Kansas conducted the 20-minute survey by phone, fax, or mail, according to responder preference. Interviewers called in advance to determine how the interview would be conducted and to set up times for the phone interviews. A computer-assisted telephone interviewing system enabled interviewers to enter data as the phone interviews took place. Respondents who preferred written surveys were faxed or mailed survey forms, which were entered into the database when they were returned. Results of the phone survey were compiled and checked weekly for errors (that is, illogical or out-of-range responses). Clinics were called back to clarify questionable responses. Before the data were analyzed, range and frequency checks were conducted on the entire database. Surveys that were administered through the mail were double entered by using two separate databases and two different data entry personnel. These databases were compared, and discrepancies were resolved before analysis. To check the accuracy of data entry for the mailed-in surveys, 10 percent of the paper surveys were randomly selected, and the hard copies were compared against the data in the database. The error rate was .02 percent

We adapted survey items from a national study of methadone treatment practices (18), a survey of nicotine dependence treatment among community health centers (19), a survey of cessation services by drug treatment professionals (12), and an extensive literature review of similar studies in a variety of health care settings. We developed a number of items to assess adherence to U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for nicotine dependence treatment (20). A draft of the instrument was administered by telephone to the clinic directors of six methadone maintenance facilities in the Kansas City area. These facilities included private for-profit, private nonprofit, and public clinics across two states. Afterwards, all directors attended a meeting at which they provided suggestions for revising the questionnaire—changing wording as well as eliminating and adding questions—and for changing survey procedures to suit the context of methadone maintenance. The final instrument included questions about the characteristics of the responder, the clinic, and the staff; whether staff routinely ask patients about smoking; whether staff assisted any patients to quit smoking in the past 30 days; what types of nicotine dependence services the program offers; what office systems are in place to support routine intervention; whether the facility has a staff "champion" who has a strong interest in treating smoking (21); and staff interest in receiving training in nicotine dependence treatment.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted by using the SAS statistical package (22). Frequencies and percentages were calculated for all categorical variables. Means, medians, standard deviations, and ranges were computed for continuous variables. Inferential statistics included chi square statistics for categorical variables. We examined data for differences by clinic size, clinic ownership, and staff size.

To assess congruence with current treatment guidelines, we constructed a measure of the provision of comprehensive nicotine dependence services. Routinely assessing smoking status, providing some form of counseling or advice, and providing bupropion or nicotine replacement therapy are practices that have the strongest ("A" level) evidence for affecting smoking cessation (20). We created a composite variable for clinics that routinely asked about smoking status on admission, provided group or individual counseling to at least one patient in the past 30 days, and had provided bupropion or nicotine replacement therapy to at least one patient in the past 30 days. We called this variable "comprehensive nicotine dependence services."

To assess how representative our sample was, we compared our sample with outpatient methadone maintenance centers that participated in the 2000 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) (23). The N-SSATS was designed to collect information from all substance abuse treatment facilities in the United States; in 2000, the overall response rate was 94 percent. Data on outpatient methadone facility size, ownership, accreditation, and region were summarized and provided by the Drug and Alcohol Services Information System (DASIS) Team (personal communication, Alderks CE, August 2002).

We conducted a logistical regression analysis to identify factors that might influence whether or not clinics provide comprehensive nicotine dependence services. To build our model we conducted univariate analyses that compared the clinics' independent variables to our dependent variable—comprehensive nicotine dependence services. We used a p<.25 level as a screening criterion for selecting which variables to include in our final model. We chose this method instead of a stepwise method because we did not want our independent variables to be selected solely on the basis of statistical criteria. The model included clinics with complete data for all variables and generated the adjusted odds ratios for providing comprehensive nicotine dependence services. The final full model included clinic ownership, whether the clinic was required to address nicotine dependence, staff training in nicotine dependence treatment, and staff interest in this treatment. Other variables in the model included having an item on the intake form for smoking status, region of the clinic, accreditation status of the clinic, clinic size, and estimated prevalence of staff who smoke.

Results

Respondent and clinic characteristics

Respondents from 59 percent of the outpatient methadone maintenance clinics in the United States (408 of 697 clinics) provided data. Fifty-four percent of the respondents (213 of 395 respondents) were female, 66 percent (268 of 408 respondents) were white, and 56 percent (214 of 381 respondents) had attended some form of graduate school. Most (274 of 345 respondents, or 79 percent) were older than 40 years. Many (211 of 383 respondents, or 55 percent) were licensed substance abuse counselors. Respondents had worked in the field for a mean±SD of 14±9.3 years. Most respondents were either current smokers (76 of 408 respondents, or 19 percent) or previous smokers (145 of 408 respondents, or 36 percent). Respondents included clinic directors, head nurses, supervising counselors, medical directors, and owners.

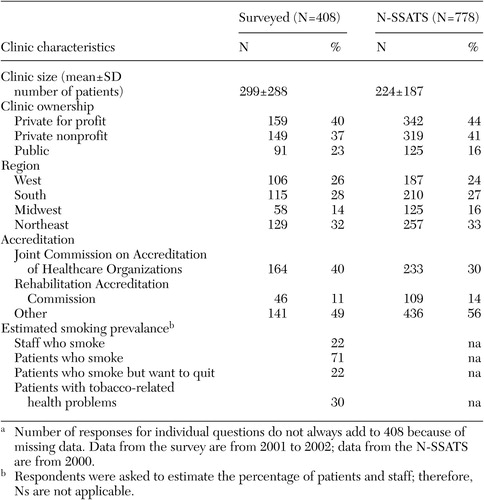

Table 1 compares characteristics of participating clinics with data from the N-SSATS. Our sample was very similar to N-SSATS respondents in terms of size, region, and ownership. Most of the clinics in our sample were freestanding facilities with ten or more staff members (data not shown). Respondents in our sample estimated that most of their patients smoked tobacco but that few were interested in quitting.

Prevalence of comprehensive nicotine dependence services

Asking about smoking. Most persons who responded to our survey (336 of 408 respondents, or 82 percent) reported that their staff routinely ask patients upon admission to treatment whether they smoke cigarettes.

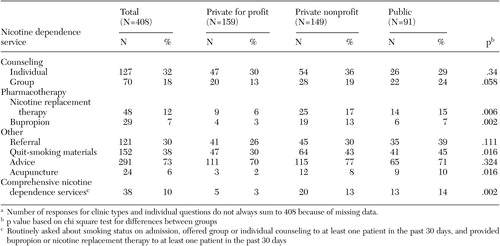

Advising patients to stop and assisting with cessation.Table 2 shows the percentage of clinics that provided nicotine dependence services to one or more patients in the past 30 days. Most clinics provided advice. One-third provided brochures, individual counseling, or referrals. Few clinics provided or prescribed nicotine replacement therapy or bupropion. One in ten clinics provided comprehensive smoking dependence services. The provision of services varied by program ownership. Markedly fewer private for-profit clinics than private nonprofit or public clinics offered group counseling, pharmacotherapy, quit-smoking materials (such as a brochure, video, or fact sheet), and comprehensive smoking dependence services.

The number of patients who received comprehensive smoking dependence services was variable but generally low. To minimize the influence of a few outliers, we report the median number of patients. Among clinics that provided each service, the median number of patients that received each service in the past 30 days were as follows: 20 were given brochures (range, 1 to 439), 17 were provided group counseling (range, 1 to 499), 11 were provided individual counseling (range, 1 to 299), five were given bupropion (range, 1 to 25), and three were given nicotine replacement therapy (range, 1 to 250).

Office systems and support for addressing smoking. Few clinics (43 of 403 clinics, or 11 percent) had written guidelines that required them to treat nicotine dependence. Most clinics (287 of 405 clinics, or 71 percent) recorded smoking status on intake forms, but few (55 of 403 clinics, or 14 percent) had stickers or charts that could be used to consistently prompt staff to address nicotine dependence. Most respondents (302 of 393 respondents, or 77 percent) agreed or strongly agreed that their clinic staff were interested in being trained to treat nicotine dependence. Just over half the clinics (221 of 394 clinics, or 56 percent) had at least one staff member who was strongly interested in treating tobacco addiction. Less than a third (121 of 402 clinics, or 30 percent) had staff who were trained in nicotine dependence treatment. No significant differences were found between clinics according to their ownership, except for staff training. A smaller proportion of private for-profit clinics had staff who were trained in nicotine dependence treatment (34 of 159 clinics, or 21 percent) compared with private nonprofit clinics (48 of 146 clinics, or 33 percent) and public clinics (38 of 92 clinics, or 41 percent) (p=.005 for all).

Correlates of comprehensive service provision

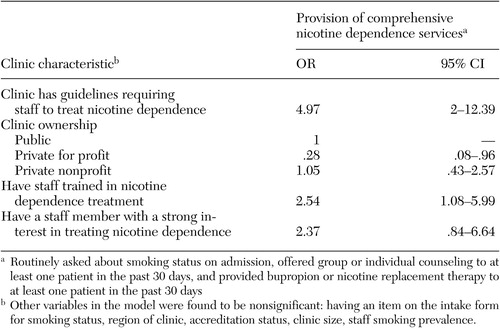

Logistic regression identified three significant correlates to the provision of comprehensive nicotine dependence services. Table 3 shows that the adjusted odds ratio for the provision of these services was 4.97 for clinics with written guidelines that required staff to treat nicotine addiction compared with those not required to do so. Compared with public clinics, private for-profit clinics had threefold lower odds of providing these services. Clinics with staff trained in nicotine dependence treatment had higher odds of providing services than those with no trained staff.

Discussion

Methadone and other opioid treatment clinics in the United States identify, but rarely treat, patients who smoke. Patients who are treated in these clinics receive substandard care for their nicotine dependence. Private for-profit clinics perform significantly worse than public clinics and private nonprofit clinics.

Too few clinics address smoking: even though a vast majority of methadone patients smoke, one out of four clinics had not advised even one patient to quit smoking in the 30 days before the survey. Two out of three clinics had not provided any form of counseling or classes for smoking cessation, and nine out of ten clinics had not prescribed nicotine replacement therapy to any patients in the 30 days before the survey.

Primary care physicians routinely treat smoking even though fewer of their patients smoke compared with patients who are in methadone treatment. For example, Goldstein and colleagues (24) conducted a population-based survey of U.S. physicians that identified the proportion of physicians who "routinely" offer smoking cessation services to patients, with "routine" defined as offering services to 80 percent or more of patients. Many physicians in the survey (35 percent) reported that they "routinely" offer help in quitting smoking. None of our clinics would have met criteria for "routinely" offering any tobacco dependence services, even though more than 70 percent of methadone patients smoke and these patients visit the methadone clinic four to 30 times monthly. The low estimates of patients who are treated for nicotine dependence in methadone clinics suggest that the provision of this service is far from routine.

Methadone clinics may not offer these services because they do not have office systems in place to support routine intervention. Nearly all methadone clinics have forms for recording smoking status. However, few have staff who are trained in offering comprehensive nicotine dependence services or office systems that promote these services and very few are required to treat tobacco smoking.

We found that only one out of ten methadone facilities offers patients a full set of recommended services for smoking cessation. Private for-profit facilities, the fastest growing provider group among methadone facilities in the United States (16), were much less likely than private nonprofit or public facilities to provide an effective set of these services. However, regardless of ownership, clinics that were required to treat smoking and that had staff who were trained in nicotine dependence treatment were much more likely to provide services that meet the standard of care.

The external validity of the findings may be limited in that methadone therapy is a distinct form of drug treatment with its own philosophy and culture. Our findings may not generalize to other treatment modes, including therapeutic communities, chemical-free outpatient treatment, and self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous.

The internal validity of our study is limited because of several factors that are common to survey research. We achieved a good but not definitive response rate from U.S. methadone clinics; therefore, the selection may be biased. We asked one person to respond on behalf of an entire facility; therefore, the findings may be more or less accurate, depending on the degree of familiarity the respondent has with day-to-day operations and also the degree to which personal biases impinge on the reporting. All data are self-reported and hence subject to recall bias. This bias affects all data but also may render some measures more or less valid than others. For example, measures of whether or not a particular service was offered in the past 30 days might be more valid, in that they are easier to recall, than measures that require specific counts of how many patients were offered services. Similarly, respondents may have overreported service rates because of optimistic bias; if so, it is possible that actual rates of service provision are worse. The survey was cross-sectional, and the findings cannot be assumed to be causal.

We found higher rates of the provision of smoking dependence services than two other studies that were conducted in substance abuse treatment centers (12,13). Similar to the study of Goldstein and colleagues (24), these two studies focused on the routine provision of smoking dependence services. Our strategy involved obtaining a 30-day prevalence of all clinics that intervened with any patient at all and then collecting estimates of how many patients were served. This approach may in part account for the differences in prevalence rates.

The efficacy of smoking cessation services among methadone patients is not known. Future research should identify effective methods for helping patients in drug treatment quit smoking and effective means for promoting the adoption of these methods in the treatment community. Trials are currently under way to identify effective smoking cessation interventions for patients in treatment for illicit drug use. How best to promote adoption by clinics of effective services is a separate and equally challenging issue. We found that mandated treatment and counselor training were associated with the provision of comprehensive nicotine dependence services. Future research could examine causal relationships between these variables and service provision—for example, whether providing staff training or requiring clinics to treat smoking increases rates of the provision of these services.

Federal regulations do not require clinics to address tobacco use in any way. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recently unveiled new regulations for opioid treatment programs in the United States (25). These guidelines are intended to focus regulation on patient outcomes and promote the adoption of state-of-the-art treatment practices (26). The guidelines require opioid treatment staff to know effective strategies for treating alcohol, cocaine, and other drug abuse but not tobacco use. In fact, no mention whatsoever of cigarette smoking is made in the guidelines. Despite this omission, providing nicotine dependence treatment could help facilities meet a number of core accreditation standards that focus on reducing the problematic use of over-the-counter and prescription drugs, improving the quality of life by restoring physical health, documenting medical history, and creating individualized patient treatment plans. In light of the poor rates of providing smoking cessation services that we found among private for-profit clinics, regulations that require some form of intervention may be necessary to ensure that all patients have access to these services.

Clinics could address nicotine dependence in much the same way that they provide mandated HIV intervention. Current methadone treatment guidelines require staff to conduct HIV testing, educate patients about HIV, and link them with community treatment. Depending on the urban area 1 to 37 percent of drug treatment patients have HIV in the United States (27). In 1999 a total of 17,000 U.S. citizens died from AIDS-related illnesses (28). In comparison, 74 to 100 percent of U.S. drug treatment patients smoke cigarettes (6,7), and more than 400,000 people die from tobacco-related illnesses annually in the United States (1). Given the overwhelming burden of nicotine dependence, it is not clear why facilities are not required to treat this dependence. Lack of resources for offering these new services may present the biggest barrier. It is important that any proposed mandate for treating smoking be accompanied by advocacy for new funding and tips on gaining access to existing funding—such as Medicaid or state-specific sources—for smoking cessation treatment.

Conclusions

Many substance abuse treatment staff are supportive of, and most patients are interested in, nicotine dependence treatment. We found that most facilities ask their patients about smoking, are interested in getting training in nicotine dependence treatment, and have at least one staff member with a strong interest in treating cigarette smoking. It appears that most clinics need and would welcome continuing education and technical assistance. A dual strategy of requiring clinics to provide comprehensive nicotine dependence services and training staff to provide these services may provide the incentive and support necessary for the widespread adoption of treatment for nicotine dependence in methadone facilities.

Acknowledgments

Daniel Alford M.D., M.P.H., helped develop the survey. Donald Haider-Markel, conducted the survey. Robert Lubran and Nicholas Reuter from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment's division of pharmacologic therapies provided facility contact information. Survey questions were trialed and critiqued by Carolyn Rowe, Keith Spare, Pam Cygan, Bridget Sams, Rose Jette, and Boyd Shumate. This study was funded by grant 042042 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Substance Abuse Policy Research Program and grant K01-DA-00450 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Dr. Richter, Dr. Choi, and Dr. Ahluwalia are affiliated with the department of preventive medicine and public health at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Mail Stop 1008, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Kansas City, Kansas 66160 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Richter, Dr. Choi, and Dr. Ahluwalia are also with the Kansas Cancer Institute in Kansas City. Dr. Harris is with the department of psychology at the University of Montana in Missoula. Mr. McCool is a private research consultant in litigation practice in Kansas City, Missouri.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of outpatient methadone maintenance facilities surveyed and those in the 2000 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS)a

a Number of responses for individual questions do not always add to 408 because of missing data. Data from the survey are from 2001 to 2002; data from the N-SSATS are from 2000.

|

Table 2. Outpatient methadone maintenance facilities that provided nicotine dependence services to at least one patient in the past 30 days, by clinic ownershipa

a Number of responses for clinic types and individual questions do not always sum to 408 because of missing data.

|

Table 3. Results of multiple logistic regression examining correlates of the provision of comprehensive nicotine dependence services among 385 outpatient methadone maintenance facilities

1. Fellows JL, Trosclair MS, Adams EK, et al: Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 51:300–303, 2002Medline, Google Scholar

2. McCarthy WJ, Zhou Y, Hser YI, et al: To smoke or not to smoke: impact on disability, quality of life, and illicit drug use in baseline polydrug users. Journal of Addictive Diseases 21:35–54, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hurt RD, Offord KP, Croghan IT, et al: Mortality following inpatient addictions treatment. JAMA 275:1097–1103, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hser Y, McCarthy WJ, Anglin MD: Tobacco use as a distal predictor of mortality among long-term narcotics addicts. Preventive Medicine 23:61–69, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Richter KP, Ahluwalia HK, Mosier M, et al: A population-based study of cigarette smoking among illicit drug users in the United States. Addiction 97:861–869, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Istvan J, Matarazzo JD: Tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine use: a review of their interrelationships. Psychological Bulletin 95:301–326, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kalman D: Smoking cessation treatment for substance misusers in early recovery: a review of the literature and recommendations for practice. Substance Use and Misuse 33:2021–2047, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Clemmey P, Brooner R, Chutuape M, et al: Smoking habits and attitudes in a methadone maintenance treatment population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 44:123–132, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Best D, Lehmann P, Gossop M, et al: Eating too little, smoking and drinking too much: wider lifestyle problems among methadone maintenance patients. Addiction Research 6:489–498, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Stark MA, Campbell BK: Cigarette smoking and methadone dose levels. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 19:209–217, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Richter K, Gibson C, Ahluwalia J, et al: Tobacco use and quit attempts among methadone maintenance clients. American Journal of Public Health 91:296–299, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hahn EJ, Warnick TA, Plemmons S: Smoking cessation in drug treatment programs. Journal of Addictive Diseases 18:89–99, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bobo JK, Davis CM: Recovering staff and smoking in chemical dependency programs in rural Nebraska. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 101:221–227, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Currie SR, Nesbitt K, Wood C, et al: Survey of smoking cessation services in Canadian addiction programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 24:59–65, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Story J, Stark MJ: Treating cigarette smoking in methadone maintenance clients. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 23:203–215, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, 1995Google Scholar

17. Frosch DL, Shoptaw S, Jarvik ME, et al: Interest in smoking cessation among methadone maintained outpatients. Journal of Addictive Diseases 17:9–19, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. D'Aunno T, Folz-Murphy N, Lin X: Changes in methadone treatment practices: results from a panel study 1988–1995. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 25:681–699, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Zapka JG, Pbert L, Stoddard AM, et al: Smoking cessation counseling with pregnant and postpartum women: a survey of community health center providers. American Journal of Public Health 90:78–84, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Fiore M, Bailey W, Cohen S: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2000Google Scholar

21. Steckler A, Goodman RM: How to institutionalize health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion 3:34–44, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. SAS Institute: SAS/STAT User's Guide, Version 8. Carey, NC, SAS Institute, Inc, 2000Google Scholar

23. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS):2000. Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. Drug and Alcohol Services Information Series S-16. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2002Google Scholar

24. Goldstein MG, Niaura R, Willey-Lessne C, et al: Physicians counseling smokers: a population-based survey of patients' perceptions of health care provider delivered smoking cessation interventions. Archives of Internal Medicine 157:1313–1319, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Opioid Drugs in Maintenance and Detoxification Treatment of Opiate Addiction; Notice of Approval of Accreditation Organizations for Opioid Treatment Programs Under 42 CFR Part 8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Federal Register 66:60215, 2001Google Scholar

26. CSAT Guidelines for the Accreditation of Opioid Treatment Programs, Washington, DC, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2002Google Scholar

27. HIV Prevalence Trends in Selected Populations in the United States: Results From the National Serosurveillance, 1993–1997. Atlanta, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001Google Scholar

28. A Glance at the HIV Epidemic, Atlanta, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002Google Scholar