A Two-Year Follow-Up Study and Prospective Evaluation of the DSM-IV Axis V

Abstract

A six-month cohort of general adult psychiatric inpatients was followed for up to two years to evaluate outcome and contrast the validity of DSM-IV measures of adaptive functioning—the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS), and the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale (GARF). Detailed data, including quality-of-life ratings and DSM-IV axis I and V codes, were collected by interview and self-report questionnaires for 53 study participants. Patients' retrospective ratings of the care they received were not predictive of outcome. Adaptive functioning at discharge was predictive of both severity of illness and social functioning at follow-up. The SOFAS had the strongest concurrent and predictive validity, the latter both for length of initial inpatient stay and two-year outcome.

To supplement the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), DSM-IV introduced two new measures of adaptive functioning for further research, namely the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) and the Global Assessment of Relational Functioning Scale (GARF). The GAF is a considerable revision of the original axis V in DSM-III, and concern has been raised (1) about the fact that it combines psychological and social functioning measures on a single axis. In contrast, the SOFAS focuses on the individual's level of social and occupational functioning while excluding severity of symptoms. The GARF is a narrower measure of quality of familial or other ongoing relationships. Research on the validity of these measures has been limited (2), especially comparisons of all three measures. Hilsenroth and colleagues (3) found the three scales to be reliable, although in their study the scales appeared to measure different constructs.

The aims of this study were to evaluate outcome, including patient satisfaction, and to compare concurrent and predictive validity of the three measures of adaptive functioning. We hypothesized that the SOFAS would have greater validity, because it assesses a narrower construct.

Methods

A total of 97 potential study participants were drawn from 100 consecutive admissions of general adult psychiatric inpatients to a large metropolitan teaching hospital between January and June 1998 (three patients were admitted twice). Patients were contacted by letter and telephone, and a researcher visited each patient at home up to three times in the process of approaching patients to participate in the study. Hospital, community services (including case managers), and general practitioner address lists were used to locate study participants and collect data.

Sixty-three (65 percent) of the 97 patients were women, and 92 (95 percent) were Caucasian. The mean±SD age of the patients was 39.9±16 years. Eighty-one patients (79 percent) were widowed, divorced, or never married. According to the initial clinician DSM-IV diagnoses, 28 patients (29 percent) had schizophrenia or another nonorganic psychotic disorder, 34 (35 percent) had a mood disorder, 11 (11 percent) had an organic mental disorder, and 22 (23 percent) had another disorder—for example, adjustment disorder. Two patients had no primary axis I diagnosis.

Demographic data, length of inpatient stay, diagnoses, and ratings of DSM-IV axes were collected by the three psychiatry registrars who worked on the ward. To encourage standardization, the registrars were supervised weekly in making ratings by the first author.

The patients were interviewed in person or, if that was not possible, by telephone, at their convenience, by the third or fifth author between January and June 2000. The interviewers were blind to the patients' baseline ratings. The interview assessed treatment and the frequency of family contact since discharge; current psychiatric status, including diagnosis by the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) (4); severity of illness as measured by the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS) (5); current GAF, GARF, and SOFAS scores; and satisfaction with inpatient and community care on the basis of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) (6). In addition, social adjustment was evaluated with the Social Adjustment Scale Self-Report—Modified (SAS-M) (7), quality of life was assessed with the 36-item Social Functioning scale (SF-36) (8), and general severity of psychiatric symptoms was assessed with the 53-item version of the Symptom Checklist (SCL-53) (9). All these instruments have robust psychometric properties.

Reliability of independent ratings in 12 joint interviews of the GAF, the GARF, and the SOFAS as well as diagnosis was assessed with intraclass correlation analyses. There was complete agreement on axis I and highly significant correlations with regard to GAF, GARF, and SOFAS ratings (α=.94, .98, and .89, respectively; p<.001 for all). There was also agreement between follow-up and initial axis I diagnoses (kappa=.50, p<.001).

Spearman ranked correlation coefficient (rs), Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used Because of multiple testing, the significance level was set at .01.

Royal Adelaide Hospital's research ethics committee approved the study.

Results

Of the 97 patients identified, 49 (51 percent) were interviewed (five by telephone). Incomplete data for 11 others (seven of whom were not included in the analysis) came from community case notes and clinician interviews. Twenty-seven patients could not be located, seven refused to participate in the study, and three had since died (two by suicide confirmed by coroner's records). The patients for whom no data were obtained at follow-up had a shorter median length of initial hospital stay (12 days compared with 21.5 days; Wilcoxon Z=-2.36, p<.02) and were more likely to be discharged to a boarding house, to another state, or to another psychiatric unit (11 of 37 patients, compared with three of 60 who were followed up). These two groups did not differ significantly in age, gender, initial GAF ratings, DSM-IV diagnostic groupings, or presence of a personality disorder.

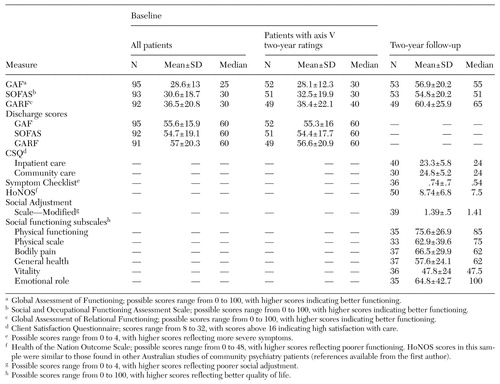

Scores on measures of adaptive functioning and illness severity at admission, discharge, and two-year follow-up are shown in Table 1. Although scores on the CSQ were high, they did not correlate with concurrent ratings from the HoNOS, the SCL-53, the SAS-M, or any SF-36 subscale or axis V measure. Participants who had had regular (average minimum twice weekly) family contact since the index admission had significantly higher ratings on the GARF (Z=-3.64, p<.001), but no significant differences were noted in SOFAS, GAF, or HoNOS ratings.

At follow-up, all three axis V measures correlated with some scores on the SAS-M (all rs>−.39, p<.02), the SCL-53 (all rs>−.43, p<.02), and SF-36 subscales (with SOFAS all had rs>.40, p<.04; with GAF all but one subscale had rs>.37, p<.03) and the HoNOS (all rs>−.68, p<.001) ratings. The SOFAS correlated with all, reaching significance on all but two subscales of the SF-36—namely, body pain (rs=.4, p=.02) and emotional role (rs=.36, p=.04.)

Both the index admission GAF scores (rs=−.23, p<.01) and SOFAS scores (rs=−.40, p<.001) but not GARF scores (rs=−.17, p<.05) showed a significant negative correlation with length of inpatient stay. After data were normalized by using the method of Blom (10), a stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed. The SOFAS score explained 12.3 percent of variance and was the better predictor of length of stay (F=5.03, df=1, 89, p=.003).

Only the SOFAS scores on discharge from the index admission were significantly correlated at follow-up with SOFAS scores (rs=.38, p<.01, N=51), GAF scores (rs=39, p<.01, N=51), and HoNOS scores (rs=−.43, p<.01, N=48).

Discussion and conclusions

Our results should be interpreted cautiously given that the study had notable limitations. Unlike the follow-up assessments, the baseline assessments were not conducted with structured and reliable instruments, and axis V follow-up data were available for only 53 of the 97 patients initially identified. This follow-up rate likely reflected the mobility of many of the participants, because those who were discharged to a boarding house, to another state, or to another psychiatric unit were less likely to have data at follow-up.

At follow-up, most of the study participants reported that their general health was at least good, and their reported ratings of the care they received were high. However, these care ratings were not predictive of outcome. This result may partly reflect distortion of patients' responses due to an inclination to say what they thought the researcher wanted to hear as well as retrospective reporting.

As in earlier studies, the DSM-IV SOFAS and GAF scores on admission were found to be significantly and negatively correlated with duration of hospital admission, and the SOFAS ratings on discharge were negatively and significantly correlated with psychiatric outcome (higher HoNOS scores indicate poorer functioning) at two years. The SOFAS appeared to have better predictive validity and concurrent validity than the GAF or the GARF. Thus the SOFAS may be a more clinically useful measure of adaptive functioning. However, the relationship between SOFAS scores and length of stay was not strong; this relationship accounted for only 12.3 percent of variance. For cases in which clinicians or researchers are specifically interested in relational functioning, the GARF may be useful.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided by the JH & JD Gunn Medical Research Foundation. The authors thank Jacqui Parsons, M.P.H., for providing the computer scoring program for the SF-36 and Robert Barrett, Ph.D., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., cocreator of the department of psychiatry's clinical database.

Dr. Hay and Dr. Katsikitis are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Royal Adelaide Hospital, North Terrace, South Australia 5001, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Begg is a consulting psychiatrist in Adelaide. Dr. Da Costa is a resident medical officer at the Repatriation General Hospital in Daw Park, South Australia, and a former student of the University of Adelaide. Ms. Blumenfeld is a postgraduate student in psychology at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, and a former student of the University of Adelaide.

|

Table 1. Scores on DSM-IV and other measures of adaptive functioning and illness severity at admission, discharge, and two-year follow-up among adult psychiatric inpatients

1. Goldman HH, Skodal AE, Lave TR: Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1148–1156, 1992Link, Google Scholar

2. Roy-Byrne P, Dagadakis C, Unützer J, et al: Evidence for limited validity of the revised Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. Psychiatric Services 47:864–866, 1996Link, Google Scholar

3. Hilsenroth MJ, Ackerman SJ, Blagys MD, et al: Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1858–1863, 2000Link, Google Scholar

4. Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, et al: The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM III-R (SCID) II: multisite test-retest reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:630–636, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Orrell M, Yard P, Handysides J, et al: Validity and reliability of the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales in psychiatric patients in the community. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:409–412, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Larsen DL, Atkinson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197–207, 1972Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Cooper P, Osborn M, Gath D, et al: Evaluation of a modified self-report measure of social adjustment. British Journal of Psychiatry 141:68–75, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McCallum J: The new SF-36 health status measure: Australian validity tests. Canberra, Australia, National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University, 1994Google Scholar

9. Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N: The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine 13:595–605, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Blom G: Statistical Estimates and Transformed Beta Variables. New York, Wiley, 1958Google Scholar