Blood-Borne Infections and Persons With Mental Illness: Gender Differences in Hepatitis C Infection and Risks Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The authors assessed gender differences in hepatitis C infection and associated risk behaviors among persons with severe mental illness. METHODS: The sample consisted of 777 patients (251 women and 526 men) from four sites. RESULTS: Across sites, the rate of hepatitis C infection among men was nearly twice that among women. Clear differences were noted in hepatitis C risk behaviors. Men had higher rates of lifetime drug-related risk behaviors: needle use (23.1 percent compared with 12.5 percent), needle sharing (17.6 percent compared with 7.7 percent), and crack cocaine use (45.2 percent compared with 30.8 percent). Women had significantly higher rates of lifetime sexual risk behaviors: unprotected sex in exchange for drugs (17.8 percent compared with 11.2 percent), unprotected sex in exchange for money or gifts (30.6 percent compared with 17 percent), unprotected vaginal sex (94 percent compared with 89.7 percent), and anal sex (33.7 percent compared with 22.6 percent). Gender appeared to modify some sex risks. Unprotected sex in exchange for drugs increased the risk of hepatitis C seropositivity for both men and women. In the multivariate model, gender was not significantly associated with hepatitis C seropositivity after adjustment for other risk factors. CONCLUSIONS: Gender differences in the lifetime rates of drug risks explain the higher rates of hepatitis C infection among men with severe mental illness.

In the United States, the rates of hepatitis C infection differ by gender: 2.5 percent for men compared with 1.2 percent for women (1). Among persons with severe mental illness, hepatitis C rates are higher and also differ by gender: 19.6 percent for men and 9.8 percent for women (2). The gender differences in infection rates among persons with severe mental illness may reflect differences in patterns of risk behaviors or in the risk associated with a given behavior. However, few studies have examined gender differences in risk behaviors for hepatitis C infection, and none have examined these issues among persons with severe mental illness.

Understanding gender differences in risks and rates of hepatitis C infection among persons with severe mental illness may help clarify the role of sexual transmission. A study of HIV risks among persons with severe mental illness found female gender to be predictive of high-risk sexual behaviors (3). The literature suggests that the hepatitis C virus may be spread sexually but less efficiently than HIV or hepatitis B. Although reports are mixed, estimates of sexual transmission of hepatitis C range from zero in some cohorts to 23 percent in high-risk cohorts (4,5,6,7). In one study, the rate of hepatitis C transmission from infected persons to their spouses (non-injection drug users) was 6 percent (8). Another study reported evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among women with or at risk of HIV infection (9). A third study did not find evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C (5).

In a large multisite study of infectious diseases among persons with severe mental illness, we investigated gender differences in the constellation of risk behaviors associated with hepatitis C infection and sought to answer three questions. First, does the prevalence of hepatitis C risk behaviors differ by gender? Second, does gender influence the risk of hepatitis C associated with a given behavior? Finally, do gender differences in hepatitis C risk behaviors account for the differences in hepatitis C infection rates between men and women?

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of data from a large multisite investigation of risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women and men with severe mental illness, described in the other articles in this special section of this issue of Psychiatric Services (10). We recruited 969 participants from five sites between June 1997 and December 1998. We excluded 192 participants at one site (Duke) who did not test positive for hepatitis C, which left a sample of 777. A detailed description of the sampling and data collection methods is provided elsewhere (2).

We used the AIDS Risk Inventory (ARI) (11) to assess risk behaviors that may be associated with hepatitis C infection. We assessed comorbid substance use disorders with the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI), a sensitive and reliable measure for substance use disorders among persons with severe mental illness (12). We tested for serum antibodies to hepatitis C with the Abbott enzyme immunoassay kit (2).

The primary outcome variable was hepatitis C serostatus. The primary independent variable was gender. The other key variables were lifetime risk behaviors, including drug risks, such as injection drug use and needle sharing, and sex risks, such as unprotected sex in exchange for money or drugs.

We stratified analyses by site because of the variability in demographic characteristics, recruitment, and sampling strategies. We assessed associations between gender and demographic variables with the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney, and Cochran-Armitage trend tests, depending on the distribution of the demographic variable. We assessed the bivariate relationships between risk and hepatitis C serostatus, risk and gender, and risk and hepatitis C serostatus for each gender. Common odds ratios (ORs) for each specified bivariate association were tested for homogeneity by the Zelen test for homogeneity of odds ratio (13). If the test for homogeneous ratio was not rejected, a common OR was calculated by the exact inference method using StatXact software (14). If the test for homogeneous odds ratio was rejected, an OR for each site was calculated and tested for significance within each site. Analyses used the SAS version 6.12 and the StatXact packages.

After assessing bivariate relationships, we performed a multiple logistic regression analysis, adjusting for site. Variables in the model were selected on the basis of their relative importance in the domains of drug- and sex-related risk behaviors and their relevance to research questions. We used casewise deletion to handle missing data in all statistical tests.

Results

Patient characteristics

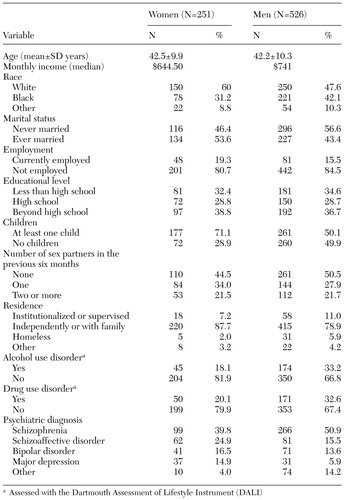

Characteristics of the 251 women and 526 men who participated in the study, stratified by gender (not adjusted for site), are summarized in Table 1. Compared with the men, the women had higher rates of ever being married and of having at least one child. The men had higher rates of institutionalization, residence in supervised settings, and homelessness than the women. Approximately two-thirds of the participants had schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. A higher percentage of women had schizoaffective disorder or mood disorders, and a higher percentage of men had a comorbid substance use disorder. Gender differences were noted in education and number of sexual partners in the previous six months—women tended to have more education and more sexual partners. These gender differences in demographic characteristics were statistically significant after we controlled for site (p<.05).

Prevalence of hepatitis C and risk behaviors

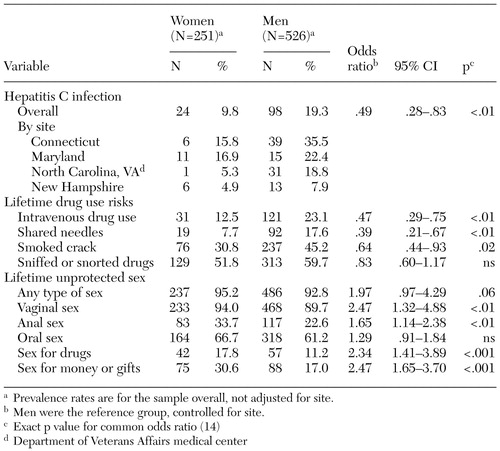

The nonadjusted prevalence of hepatitis C and selected hepatitis C risks stratified by gender and the common ORs for gender and these risks are shown in Table 2, with men as the reference group. At each of the five sites, the rate of hepatitis C infection was higher for men, ranging from 7.9 percent to 35.5 percent, compared with 4.9 percent to 16.9 percent for women. Men had significantly higher rates of lifetime drug risks than did women: needle use, needle sharing, or crack cocaine use. Women were significantly less likely than men to have ever used injection drugs, shared needles, or smoked crack.

Women had significantly higher rates of lifetime sex-related risk behaviors than did men: unprotected vaginal sex, anal sex, unprotected sex in exchange for drugs, and unprotected sex in exchange for money or gifts. More than 90 percent of both men and women had unprotected sex during their life, and 44 percent had unprotected sex within the previous six months. Women were significantly more likely than men to have lifetime unprotected vaginal and anal sex. Women were also more likely than men to have had sex in exchange for drugs or for money or gifts during their lifetime. Similar gender-based trends in sex-related risk for the six months before the risk interview were also noted.

Gender as a modifier of risks

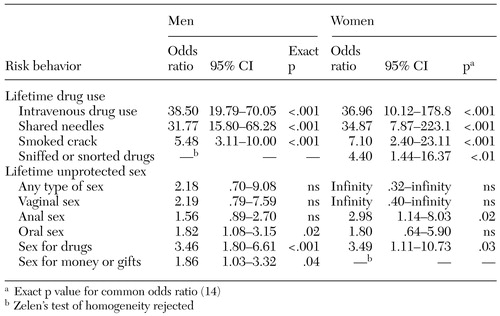

Table 3 presents the lifetime risks and common ORs for hepatitis C seropositivity, controlled for site and stratified by gender. The drug-related risk behaviors, including lifetime injection drug use, sharing needles, and smoking crack, were associated with hepatitis C seropositivity for both men and women. Among the unprotected lifetime sex-related risks, anal sex for women (but not men) and oral sex for men (but not women) were associated with a significant increase in the odds of hepatitis C seropositivity. Unprotected sex in exchange for drugs was associated with a higher risk of hepatitis C seropositivity for both men and women.

To further understand hepatitis C risks, we reviewed specific risks among the study participants who were infected with the hepatitis C virus (98 men and 24 women). Of this group, 31 participants (25 percent) did not report any lifetime needle use: 22 (71 percent) were men, and nine (29 percent) were women. Among the hepatitis C-positive men, 17 reported other drug risks that could explain the hepatitis C infection, and four reported three or more high-risk sex behaviors. Among the hepatitis C-positive women, seven reported other drug-related risks, and four reported three or more high-risk sex behaviors.

Multivariate analysis

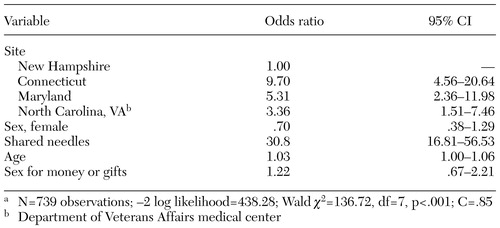

The results of our multiple logistic regression analysis of risk factors related to hepatitis C are presented in Table 4. After we adjusted for other important factors, gender was not significantly associated with hepatitis C seropositivity, although the OR was higher for men than for women. Site, age, and needle sharing were all significantly related to hepatitis C infection. The OR for site ranged from 3.36 for the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) site in North Carolina to 9.70 for the Connecticut site. (New Hampshire was treated as the reference group.) This analysis showed that both needle use and older age were associated with an increased odds of hepatitis C infection and is discussed more extensively in the article by Osher and colleagues (15) in this issue of Psychiatric Services.

Discussion and conclusions

This is the first study to examine gender differences in behavioral risks and the relationship of these differences to the very high rates of hepatitis C reported for men and women with severe mental illness (2). In addition to the twofold rates of hepatitis C among men compared with women, we also found significant gender differences in patterns of hepatitis C risk behavior. Women had significantly more sexual risk behaviors than did men, whereas men had significantly more drug-related risk behaviors than did women. Overall, our data show striking gender differences in patterns and types of risk behaviors. Our data suggest that gender may modify some of the sexual risks, but the high risk of hepatitis C associated with drug use behaviors appear similar for men and women.

Male gender did not contribute independently to the risk of hepatitis C infection, whereas site, age, and needle sharing were significantly related to hepatitis C serostatus. The higher rates of hepatitis C among men can be explained primarily by lifetime exposure to injection drug use—specifically, needle sharing. The gender differences in drug risks that we observed have been reported for other populations. The findings of higher lifetime rates of illicit drug use and substance use disorders among men than among women are consistent across studies (16,17,18,19,20,21). Our analysis confirms the importance of drug-related risks, particularly needle sharing, as a component of risk for hepatitis C for both genders. Osher and colleagues (15) provide a focused analysis of the importance and complexity of drug risks in hepatitis C transmission. The site-specific effect we observed differs from that observed by Osher and colleagues in part because of differences in the inclusion criteria.

We also observed significant gender differences in sexual risk behaviors. Compared with men, women had significantly more lifetime unprotected sex risks, including vaginal sex, anal sex, sex in exchange for drugs, and sex in exchange for money or gifts. These sexual risks do not appear to play a major role in hepatitis C transmission. However, given that there were only 24 hepatitis C-positive women in the sample, we were unable to model risks separately by gender. When we examined the specific risks in hepatitis C-positive participants who did not use needles, the suggestion of a cumulative role for multiple sexual risk factors emerged. Our results are consistent with other reports of gender differences in the rates of HIV sexual risks (3). For example, one study of injection drug users noted that women had higher sexual risks than did men and that they engaged in behaviors that protected their partners more often than themselves (22).

Because of the high baseline rates of sex-related risk behaviors and gender differences in patterns of risk, we were able to evaluate the relationship of sex risks to hepatitis C serostatus and compare these risks between men and women. In the bivariate analysis, several sexual risks were significantly associated with hepatitis C serostatus. These associations suggest that gender may modify several of these sexual risks. However, in the logistic regression model, sexual risk behaviors did not contribute independently to the risk of hepatitis C infection. Our results are consistent with those of a study that evaluated patients at a sexually transmitted diseases clinic (5). The authors of that study concluded that sexual risks do not play a major role in hepatitis C transmission, although that sample was primarily male.

The results of other studies support a more prominent role of sexual transmission of hepatitis C among women (9,23,24,25,26,27). One study found evidence for sexual transmission of hepatitis C among HIV-infected or at-risk women in Chicago (9). In that study, injection drug use was the strongest predictor of hepatitis C infection among women, as it was in ours, but sexual risks—history of gonorrhea or sex with an injection-drug-using partner—were also independently associated with hepatitis C infection. Another study of injection drug use among men found that 10 percent of the men's women partners (non-injection-drug users) were infected with the hepatitis C virus, suggesting that sexual transmission of hepatitis C from infected men to their female partners may occur and that women partners of men who inject drugs are at risk (24).

Blood-to-blood contact is important for hepatitis C transmission, and there appears to be convergent evidence for sexual transmission. It has been theorized that menstruation, anal sex, and concurrent sexually transmitted diseases are all hepatitis C risk factors for women (25,26). This theory is especially salient for women with severe mental illness, who have high rates of sexual risk behaviors. Although sex was not the prominent mode of hepatitis C transmission in our study sample, the high rates of sexual risks that we observed among women with severe mental illness are of concern. Gender appears to modify the risk conveyed by some sexual risk behaviors. For example, for women but not men, lifetime unprotected anal sex did convey a risk of hepatitis C transmission in the stratified bivariate analysis. This gender difference may be related to which partner is receptive during anal sex. However, we did not query to obtain this information. Sexual risk behaviors are also associated with a high risk of HIV, hepatitis B, and other sexually transmitted diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines on hepatitis C risk reduction recommend condom use to persons at risk of sexually transmitted diseases (27).

Our study had several limitations. Whereas injection drug use was the single most important risk factor predicting hepatitis C seropositivity, the actual role of high-risk sex behaviors could not be ascertained in our cross-sectional study. Furthermore, there were sampling differences across sites, although we controlled for these differences in our analysis. Given the cross-sectional study design, we were able to draw correlational inferences only. Respondents may resist disclosing socially stigmatized high-risk behaviors in a personal interview. To address this possibility, our research group is currently assessing the validity of computer-assisted risk interviews among persons with severe mental illness.

Our study raises several important clinical issues for mental health care providers. First, men and women with severe mental illness have a high risk of hepatitis C. Because significant gender differences in hepatitis C risk behaviors exist, different assessment and education strategies for men and women that target the highest domains of risk may be warranted. Thus provider interventions can be informed by knowledge of hepatitis C risks and gender differences in patterns of risk.

Hepatitis C issues for women and their partners have been reviewed elsewhere (28), and several points are especially relevant to women with severe mental illness. Our risk data suggest that spending more time educating women about sexual risk reduction may be indicated—for example, role-playing to minimize sexual risks. Other clinical issues for women with severe mental illness who are infected with the hepatitis C virus include the risks of vertical transmission (4 percent to 18 percent) and breastfeeding (probably low risk) (29,30). The rate of depression is twice as high among women and is a relative contraindication to hepatitis C treatment with alpha interferon. Although there have been case reports of treating hepatitis C-infected persons with a history of depression, more treatment studies need to be done (31).

Adequate clinical time is warranted for assessing drug and alcohol risks among men with severe mental illness. Given the compelling data on risk of lifetime injection drug use and the high rates of this risk behavior among men with severe mental illness, it is also important that mental health clinicians understand and assess these risks. Further, alcohol dependence—also common among men with severe mental illness—is known to promote the progression of hepatitis C-related liver disease. Although both depression and alcohol abuse are relative contraindications to hepatitis C retroviral treatment with alpha interferon, the research in this area is minimal. A final point is that many men and women with severe mental illness take multiple medications, some of which are hepatically metabolized. The clinical implications of this for hepatitis C-infected persons—liver function and progression of liver disease—need to be evaluated.

Dr. Butterfield, Dr. Bosworth, Dr. Meador, Ms. Stechuchak, Dr. Bastian, and Dr. Horner are affiliated with the Health Services Research and Development Service (152), Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, 508 Fulton Street, Durham, North Carolina 27705 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Essock is with the department of psychiatry of Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City and the Bronx VA Medical Center. Dr. Osher is with the department of psychiatry of the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. Dr. Goodman is with the department of counseling, developmental, and educational psychology at Boston College. Dr. Swanson is with the department of psychiatry of Duke University Medical Center in Durham. This article is part of a special section on blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of persons with severe mental illness who participated in a study of gender differences in hepatitis C infection

|

Table 2. Hepatitis C infection and risk behaviors among persons with severe mental illness in a study of gender differences in hepatitis C infection

|

Table 3. Odds of hepatitis C infection by risk behaviors, stratified by gender, among persons with severe mental illness, controlling for site

|

Table 4. Multiple logistic regression model for hepatitis C infection among persons with severe mental illnessa

a N=739 observations; -2 log likelihood=438.28; Wald χ2=136.72, df=7, p<.001; C=.85

1. Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, et al: The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. New England Journal of Medicine 341:556-562, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al: Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 91:31-37, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Otto-Salaj LL, Heckman TG, Stevenson LY, et al: Patterns, predictors, and gender differences in HIV risk among severely mentally ill men and women. Community Mental Health Journal 34:175-190, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Everhart JE, Di Bisceglie AM, Murray LM, et al: Risk for non-A, non-B (type C) hepatitis through sexual or household contact with chronic carriers. Annals of Internal Medicine 112:544-545, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fiscus SA, Kelly WF, Battigelli DA, et al: Hepatitis C virus seroprevalence in clients of sexually transmitted disease clinics in North Carolina. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 21:155-160, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Fairley CK, Leslie DE, Nicholson S, et al: Epidemiology and hepatitis C virus in Victoria. Medical Journal of Australia 153:271-273, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hess G, Massing A, Rossol S, et al: Hepatitis C virus and sexual transmission. Lancet 2:987, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Pachucki CT, Lentino JR, Schaaff D, et al: Low prevalence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus in sex partners of seropositive intravenous drug users. Journal of Infectious Diseases 164:820-821, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hershow RC, Kalish LA, Sha B, et al: Hepatitis C virus infection in Chicago women with or at risk for HIV infection. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 25:527-532, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rosenberg SD, Swanson JW, Wolford GL, et al: The Five-Site Health and Risk Study of blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:827-835, 2003Link, Google Scholar

11. Chawarski MC, Pakes J, Schottenfeld RS: Assessment of HIV risk. Journal of Addictive Diseases 17:49-59, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Rosenberg SD, Drake RE, Wolford GL, et al: The Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI): a substance use disorder screen for people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:232-238, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Agresti A: Categorical Data Analysis. New York, Wiley, 1990Google Scholar

14. StatXact 3 for Windows User Manual, 4th ed. Cambridge, Mass, Cytel Software Corporation, 1996Google Scholar

15. Osher FW, Goldberg RW, McNary SW, et al: Substance abuse and the transmission of hepatitis C among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:842-847, 2003Link, Google Scholar

16. Packer LE, Davis TR, Kroutil LA, et al: Summary of findings from the 1998 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. NHSDA publication series H-10. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1999Google Scholar

17. Brady KT, Randall CL: Gender differences in substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 22:241-251, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Bucholz KK: Nosology and epidemiology of addictive disorders and their comorbidity. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 22:221-240, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, et al: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:313-321, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Rosenberg SD, et al: Substance use disorder in hospitalized severely mentally ill psychiatric patients: prevalence, correlates, and subgroups. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:179-192, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Gollub EL, Rey D, Obadia Y, et al: Gender differences in risk behaviors among HIV+ persons with an injection drug use history: the link between partner characteristics and women's higher drug-sex risks: the Manif 2000 Study Group. Sexually Transmitted Infections 25:483-488, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Ward H, Pallecaros A, Green A, et al: Health issues associated with increasing use of "crack" cocaine among female sex workers in London. Sexually Transmitted Infections 76:292-293, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Cilla G, Perez-Trallero E, Iturriza M, et al: Possibility of heterosexual transmission of hepatitis C virus. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 10:533-534, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Sladden TJ, Hickey AR, Dunn TM, et al: Hepatitis C transmission on the north coast of New South Wales: explaining the unexplained. Medical Journal of Australia 166:290-293, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Salvaggio A, Conti M, Albano A, et al: Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus and HIV-1 infection in female intravenous drug users. European Journal of Epidemiology 9:279-284, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 47(RR-19):1-39, 1998Google Scholar

28. Mazza D: Hepatitis C: issues for women and their partners. Australian Family Physician 27:795-798, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

29. Hunt CM, Carson KL, Shararra AI: Hepatitis C in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology 89:883-890, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Salleras L, Bruguera M, Vidal J, et al: Importance of sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus in seropositive pregnant women: a case-control study. Journal of Medical Virology 52:164-167, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Gleason OC, Yates WR: Five cases of interferon alpha induced depression treated with antidepressant therapy. Psychosomatics 40:510-512, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar