Using Qualitative Methods to Distill the Active Ingredients of a Multifaceted Intervention

Abstract

Mental health studies frequently involve multifaceted psychosocial interventions. It may be difficult to isolate the active ingredients that make these interventions successful. This study examined the use of qualitative methods to better understand the content of one of these interventions and to help elucidate the links between the care process and health outcomes. A series of five focus groups were convened at a site remote from a model primary care clinic for veterans. Transcripts of the focus groups were analyzed to identify themes and categorize results for patients with serious mental disorders. Three themes emerged from the groups: the difficulty patients had previously faced in obtaining medical care, the flexibility and availability of resources that defined the clinic culture, and organizational restructuring that allowed enhanced communication. Qualitative methods can be a useful means of "unpacking" multifaceted mental health services interventions. These methods may make it possible to refine and disseminate these models more widely.

Since their introduction after World War II, randomized controlled trials have helped guide the development of science (1). In cases of discrete procedures, such as surgery, it is relatively easy to assess the link between the intervention and patient outcomes. However, mental health services research frequently involves multifaceted interventions that can be challenging to replicate and disseminate (2). A key step is to isolate the active ingredients that contributed to patient improvements. These factors may include not only the typical variables that are easily measured but also complex interactions among patients, providers, and systems of care.

Qualitative research is useful for generating hypotheses (3) and for enriching study findings by providing information about participants' perceptions and opinions that cannot be obtained through other methods (4). One qualitative method—the focus group—uses open-ended questions in an environment that fosters the sharing of ideas in an ongoing discussion format (5). This method provides one potential strategy for understanding the content of care in a complex clinical program.

In this study we used focus groups to evaluate the process of care in an integrated primary care clinic for veterans with major psychiatric disorders. The model clinic was designed in the tradition of the collaborative stepped-care clinic (6), with the goal of optimizing medical treatment of patients with serious mental illness. The clinic comprises a group of integrated services, including on-site primary medical care, medical case management, and active collaboration and communication between primary medical care and mental health providers.

In the initial study, which took place between September 1997 and November 2000, patients were randomly assigned to receive either care as usual in the regular medical clinic or care in an integrated primary care clinic, and outcomes were compared between the two groups (7). Patients in the integrated care clinic had significantly greater improvement in health status than those in the general medical clinic, as measured by changes in the physical component summary score (8) of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) over time. In addition, the patients treated in the integrated primary care clinic had better quality of care than those treated in the general medical clinic, on the basis of adherence to primary care treatment guidelines.

The goal of this study was to use qualitative methods to identify features of the multifaceted intervention that might have played a role in positive outcomes.

Methods

In the initial study, all mental health providers were asked to refer any patient who did not have a primary care provider for assignment to a medical treater. Patients were selected from mental health clinics that treated mood and psychotic disorders, substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety disorders.

For the study reported here, focus group participants were chosen by using purposeful sampling to obtain a diverse mix of participants. This sampling strategy involved deliberately selecting participants who reflected the range of characteristics of the patients and providers in the clinic. There were five focus groups—two for clinicians and three for patients, each comprising persons involved with the integrated primary care clinic. All patients who participated in the initial integrated clinic component of the study and were still enrolled in the clinic at the time of recruitment were eligible for inclusion in a focus group. Potential participants who had been selected were first contacted by telephone or letter. If they agreed to participate they received a written invitation. Patients were given the incentive of monetary compensation, and both patients and providers were provided with refreshments. The local VA and university institutional review boards approved recruitment and study procedures.

Focus groups were conducted by using a method described by Krueger (4). Under this method, each group meets for a predetermined amount of time. To ensure accuracy, the group is audiotaped (with the participants' permission) while an assistant moderator takes notes. Using an interview guide that is thoroughly reviewed by the study's primary investigators, the moderator asks open-ended questions. This approach gives participants an opportunity to express important ideas that may not be included in the initial inquiry.

The focus groups met for one hour in a conference room at the Department of Veterans Affairs hospital. To maximize sharing of information, the groups were composed of homogeneous members in terms of diagnosis (in the case of the patient groups) and clinician type (in the case of the provider groups) (4). One provider group was composed of medical clinicians from the integrated primary care clinic, and the other group included mental health providers from all psychiatric treatment teams. Each of the focus groups met once for a period of one hour between August and December 2000.

The questions were sequenced to maximize group participation and to encourage insightful thinking about group members' experiences. We started with questions that introduced the topic and allowed participants to warm up and share opinions before answering key questions. The questions were designed to enable understanding of care delivered in the clinic as well as aspects of care that seemed to be associated with improved outcomes.

Participants in the patient groups were asked what made the clinic different from other medical clinics, how clinic experiences helped contribute to changes in physical health status, and the nature of patient-provider interactions, such as goal setting. In keeping with common focus group methods (5), group members were encouraged to interact and to allow their views to change after they had listened to the insights of other group members. Participants in the provider groups were asked questions to solicit information such as how the clinic compared with other places they had worked, how their experience with patients differed according to diagnosis, whether the approach and philosophy of the clinic could be duplicated, characteristics of the patients referred to the clinic, and features of the clinic they found the most helpful.

Strategies suggested by experts in qualitative research were used to ensure that the analysis was systematic and verifiable (9). The use of both a moderator and a second observer enhanced the accuracy of data recording. Key points made by group participants were restated at the end of each session to ensure correct interpretation. The moderator and the assistant moderator met immediately after each group session to capture first impressions and highlights.

The tapes were transcribed verbatim, and transcript data were analyzed by using axial coding to categorize responses and identify themes. Each unique idea in the text was assigned a label or code (9), and the text was then rearranged to form themes. In an iterative process, data were compared within and across groups to identify patterns, make comparisons, and contrast new and old data. Using the final version of the code structure, members of the research team came together to achieve consensus and assign codes to observations by group process. Categories of data were combined into broader recurrent themes, which formed the basis of the conceptual model (10). After the data were analyzed, preliminary reports were shared among stakeholders, including researchers and clinicians, for comment. These systematic verification steps were used to avoid moderator bias.

Results

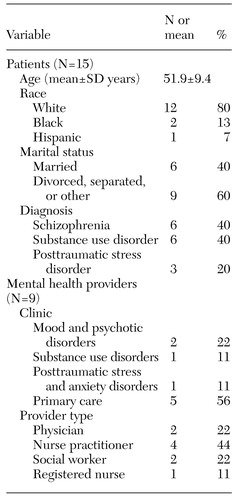

A total of 58 potential participants were identified and contacted for the patient focus groups. Of these, 15 participated in the groups, for a response rate of 26 percent. The two provider focus groups had a total of nine members. Providers of all types participated in the primary care and mental health provider groups, and all three mental health clinics and the integrated primary care clinic were represented. Characteristics of group participants are summarized in Table 1.

When asked what types of features of the clinic contributed to its success in improving health outcomes for people with severe mental illness, patients and providers expressed ideas that were categorized into eight distinct concepts: patient characteristics (for example, willingness to seek care), provider characteristics (predisposition toward treating persons with severe mental illness), clinic culture (an ideology of doing whatever was necessary to deliver care to patients), clinic resources (the ability of providers to spend enough time with patients to address a wide range of health-related needs), patient-provider trust (the relationship that developed between patients and clinical staff), provider coordination (collaboration between mental health and medical providers), care coordination (concrete tasks that link patients with care—for example, case managers' escorting patients to specialty appointments and diagnostic testing as needed), and clinic environment (a calm atmosphere in which patients could wait).

These concepts were mapped to three themes by the same methods of comparison and group consensus that were used in the initial categorization of data from transcripts to conceptual models (5,10). The three themes that emerged when participants were asked to describe unique features of the integrated primary care clinic were obstacles to medical care, flexibility and the availability of resources, and organizational restructuring, including the interdisciplinary nature of the team and effective communication between primary care and psychiatry providers.

Obstacles to medical care

Patients with PTSD, substance use problems, and schizophrenia reported that before their enrollment in the clinic, they had been turned away from medical clinics at some time. They felt a general lack of respect and reported that their medical problems were often thought to be psychiatric in origin and were often dismissed. Over time, these kinds of frustrating experiences affected their willingness to seek medical care.

Flexibility and resources

The intervention required a commitment of physical space and staff resources. Clinicians in the integrated clinic had reduced the size of the patient panel to enable them to spend more time per visit and to improve scheduling flexibility.

Patients stated that having a nurse- case manager to help them navigate the health care system was important for maintaining continuity of care. They expressed their frustration with the overstimulation of medical clinics they had visited in the past. Clinicians felt that their patients had difficulty dealing with large crowded waiting rooms and that the patients might leave before receiving needed medical care. Having a smaller clinic with a relaxed waiting room and shorter waiting times was helpful for ensuring that the patients attended their medical appointments.

Organizational restructuring

Patients and staff noted that the interdisciplinary nature of the team and the additional staff resources improved the ability to assess and treat medical problems in the context of psychiatric illness. By considering patients' needs as well as providers' agendas, clinic staff built trusting partnerships with patients so that common treatment goals could be established. Some staff expressed the goal of establishing a "family environment" in the clinic.

Several patients were made aware that they had chronic medical conditions, such as high cholesterol or blood pressure. With this knowledge, they made health behavior changes that were supported by clinic staff. Some patients reported that this was the first time they had spoken about such matters with a primary care provider.

Both medical and mental health clinicians said they felt they benefited from regular contact with each other. The patients were aware of communication among their clinicians, and they responded positively. The clinic staff felt that communication between psychiatry and primary care patients was especially helpful in dealing with somatizing patients.

The sequence and phrasing of the focus group questions elicited additional information about clinic culture, obstacles to medical treatment for persons with serious mental illness, and the importance of provider flexibility and of the care environment that was useful for the qualitative analysis.

Discussion and conclusions

The use of a qualitative approach in this intervention revealed some of the difficulties that patients with severe mental illness face when they try to obtain primary medical care and identified clinic features that may have led to improved patient outcomes. Two broad categories of active ingredients for the integrated primary care clinic were also suggested. First, the clinic provided greater flexibility and more time for appointments than do general medical clinics. Second, the integrated approach facilitated communication between patients and providers and between medical and mental health providers.

The insights gained from this study can be used to set up and evaluate systems of medical care for patients with mental disorders. The results helped to guide the development of a medical case management program that will incorporate the hypothesized active ingredients and test whether they are linked to improved health outcomes and receipt of appropriate medical care for patients with mental disorders. Specific survey instruments will measure these constructs and their impact on outcomes.

The focus group and other qualitative methods are subject to limitations. They cannot be used for hypothesis testing, and the results obtained are less reproducible than those derived from the systematic inquiry that characterizes most standardized questionnaires. However, use of focus groups can add valuable information to studies on quality and outcomes by helping to clarify the elements that contribute to treatment success.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robert A. Rosenheck, M.D., Elizabeth H. Bradley, Ph.D., Madeleine Pellerin, A.P.R.N., and Marilyn Ollayos, R.N.

Ms. Levinson Miller and Dr. Rohrbaugh are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Yale University, 950 Campbell Avenue/182, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Druss is affiliated with the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients and providers in focus groups about an integrated primary care clinic for persons with serious mental illness

1. Fuchs FD, Klag MJ, Whelton PK: The classics: a tribute to the fiftieth anniversary of the randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 53:335-342, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Katon W, Robinson P, von Korff M, et al: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:924-932, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Crabtree B, Miller W: Doing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1999Google Scholar

4. Krueger RA: Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1994Google Scholar

5. Krueger RA: Analyzing and Reporting Focus Group Results. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1997Google Scholar

6. Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, et al: Collaborative management of chronic illness. Annals of Internal Medicine 127:1097-1102, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, et al: Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:861-868, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, et al: Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Medical Care 33:AS264-AS279, 1995Google Scholar

9. Miles M, Huberman AM: Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1994Google Scholar

10. Glaser B, Strauss A: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York, Aldine de Gruyter, 1967Google Scholar