Alcohol & Drug Abuse: Principles of Money Management as a Therapy for Addiction

Money is a well-recognized cue for drug use (1). Several studies have reported evidence of an increase in substance abuse and in its adverse effects around the beginning of the month, when income checks are typically received (2). In response to this observed connection between receipt of funds and substance use, nonspecific money management interventions are often provided. A payee may be administratively mandated for beneficiaries of Social Security Disability Insurance, Supplemental Security Income, and veterans benefits. Voluntary clinical interventions, such as intensive case management, often include money management as one of several components in a broad service delivery package.

Despite the frequent use of payeeship and money management components of case management, neither approach has been developed as a fully articulated intervention. One reason for the lack of well-defined money management-based therapies is that money management is often thought of as an involuntary restriction of liberty, more akin to criminal probation than to recovery-oriented rehabilitation. Money management is frequently perceived as being coercive and adversarial and is thought to undermine patients' autonomy (3). It is thus often seen as the direct antithesis of a recovery-oriented approach to rehabilitation.

A conceptualization of money management is needed that goes beyond the simple interruption of impulsive spending to also emphasize the affirming, positive goals of money management. A bank account can represent control over one's life and choices. Clients can use saved funds to reward themselves when goals are achieved or can continue to save funds to achieve material representation of their clinical progress.

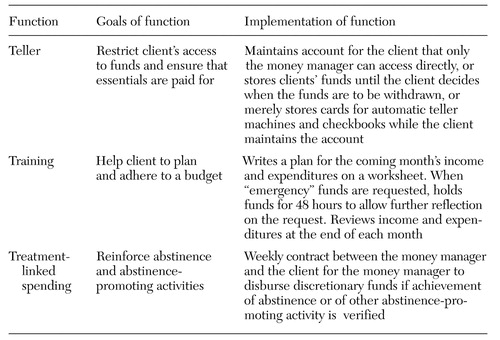

We propose a conceptualization of money management as a specific therapy that targets drug addiction and involves three functions. The first is an administrative—or "teller"—function, whereby mismanagement of funds is curtailed by controlling access to the client's bank account. The second function involves training the client to make a budget and plan expenditures. The third function incorporates behavioral principles by using discretionary spending to reinforce constructive activities and sobriety. These three functions, listed in Table 1, can be remembered as the "three T's"—teller, training, and treatment-linked spending.

The three T's

Teller function

The teller function serves two basic purposes: to restrict the client's access to funds and thus prevent misspending, and to ensure that essentials—shelter, utilities, and food—are paid for. A money manager may mediate or restrict the client's access to funds through three basic arrangements.

The first arrangement, and the one that most tightly restricts the client's access to funds, is the establishment of a bank account to which the money manager has exclusive access—for example, when a representative payee maintains a bank account for a client.

Under the second type of arrangement, the client voluntarily agrees that his or her funds will be deposited into another person's or institution's account. Some residential facilities adopt such an approach in that they receive clients' checks, arrange for immediate payment of rent, and store the remainder of the funds in a pooled account for payment of future expenses. The money manager tracks the client's balances in this pooled account and accesses the account when directed to do so by the client.

Under the third arrangement, the client voluntarily gives the money manager a checkbook or a card for an automatic teller machine, thus partially limiting the client's ability to access the account. The account remains in the client's name, and the client writes all the checks. Clients are encouraged to establish a direct-deposit account and to bring any other income to meetings with the money manager so that the income can be mailed to the bank for deposit. This arrangement is less restrictive than the first two, because the client retains access to his or her funds and can simply go to the bank and make a withdrawal.

Training function

The training function provides collaborative guidance on money management both under routine budgeting circumstances and under "emergency" or "high-pressure" circumstances. Under routine, "low-pressure" circumstances, clients are taught to budget their funds and to plan their expenditures through a series of worksheets that involve detailing anticipated sources of income and expenses for the upcoming month. At the end of the month, the clinician and the client return to this worksheet to review actual expenditures for the month and how they were paid—for example, by check or by cash. The information from this review is used to plan the budget for the next month. The budget is signed by the client and the money manager to indicate their agreement with the plan.

Under emergency or high-pressure circumstances, the client comes to the case manager at an unscheduled time with an urgent need for funds. The original contract between the client and the money manager anticipates this situation by including an agreement that the client will allow the money manager to put a two-day hold on access to discretionary funds if two conditions are met: the client suddenly wants funds that have not been previously budgeted for, and the case manager thinks the expenditures may not represent a positive use of funds. The hold is based on the presumption that the impulse to spend needs further consideration to determine whether the proposed expenditure would undermine the achievement of broader goals. The hold gives the client time to reconsider whether his or her request for funds might be a result of drug craving or an ill-considered impulse. If the client persists in this request, the hold will be relinquished and the client will be given access to the money.

Treatment-linked spending

The third function—treatment-linked spending—is used to reinforce abstinence and abstinence-promoting activities by building on procedures used in contingency management interventions—that is, those in which clients receive prizes or vouchers contingent on the achievement of certain conditions set by the therapist (4). The client agrees to reward him- or herself from saved discretionary funds if predetermined treatment goals are met.

Three important principles underlie treatment-linked spending. First, agreements or contracts between the client and the money manager are an explicit part of the therapy at the time of enrollment. Second, contracting involves not only withholding funds but also disbursing funds for client-directed purchases when goals are achieved. Third, the treatment goals that are linked to spending are negotiated between the client and the money manager. Treatment-linked spending is similar to therapeutic contracting (5) in that the client negotiates the terms of the contracts. Thus it differs from classical contingency management.

Treatment-linked spending may involve contracting directly around toxicology-verified abstinence or around broader treatment goals, most of which have at least an indirect connection to abstinence. A comprehensive list of tasks is available in an article by Petry and colleagues 2001 (6). At least one activity should be a task that is likely to be easily accomplished. Money managers should select easier tasks if clients fail at the initial task to ensure that clients experience positive reinforcement (7). For example, a client who identifies a goal of making friends who abstain from drugs might be reinforced for going to a meal with one such friend (and showing the money manager the receipt for the meal). Failing that, the client might be given reinforcement for making a list of potential friends who do not use drugs. In our experience with implementing this principle, clients often prefer to designate these funds for a purpose that requires many weeks of saving. For some clients, simply tracking the growth of savings toward a broadly defined goal—for example, retirement—is itself reinforcing.

Conclusions

Money management need not be seen as a restrictive, adversarial intervention but can be designed as a recovery-oriented, skill-building endeavor. The three money management functions—teller, training, and treatment-linked spending—involve fundamentally rehabilitative rather than restrictive activities. There is now a pressing need to determine the efficacy of money management as a therapy, whether it be implemented as part of payeeship (8) or voluntarily. On the basis of the principles outlined, we have ourselves developed an intervention that we refer to as ATM—advisor-teller-money manager—that has been successfully implemented and is currently being tested in a clinical trial.

Clients are harmed when funds that could be used to improve their quality of life are used to buy drugs. Furthermore, the fact that some disability income is spent to purchase drugs undermines public support for vital programs that provide subsistence incomes to disabled persons. One intuitive solution to this problem—simply restricting clients' access to funds—may be of little use and may merely serve to make clients feel coerced and devalued. Thus there is an urgent need for therapeutic approaches that can help clients manage their funds. Money management holds the promise of replacing spending for self-destructive drugs with spending that helps clients achieve their chosen goals.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants R01-DA12952 and P50-DA09241 from the National Institutes of Health, by the Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Integrated Service Network 1 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Care Center, and by a grant from VA Health Services Research and Development.

Dr. Rosen is staff psychiatrist at the Department of Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, and associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven. Ms. Bailey is director of co-occurring disorders programming at Connecticut Mental Health Center and clinical instructor in psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Rosenheck is professor of psychiatry and public health and director of the division of mental health services and treatment outcomes research in the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine. Send correspondence to Dr. Rosen at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Department of Psychiatry, 116A, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). Sally L. Satel, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. The three functions of a money manager

1. O'Brien CP, Childress AR, McClellan T, et al: Integrating systemic cue exposure with standard treatment in recovering drug-dependent patients. Addictive Behavior 15:355-365, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Shaner A, Eckman TA, Roberts LJ, et al: Disability income, cocaine use, and repeated hospitalization among schizophrenic cocaine abusers: a government sponsored revolving door? New England Journal of Medicine 333:777-783, 1995Google Scholar

3. Brotman AW, Muller JJ: The therapist as representative payee. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:167-171, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, et al: Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:568-576, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Berglas S, Levendusky PG: Therapeutic contract program: an individual-oriented psychological treatment community. Psychotherapy 22:36-45, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Petry NM, Tedford J, Martin B: Reinforcing compliance with non-drug-related activities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 20:33-44, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Iguchi MY, Belding MA, Morral AR, et al: Reinforcing operants other than abstinence in drug abuse treatment: an effective alternative for reducing drug use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:421-428, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ries RK, Dyck DG: Representative payee practices of community mental health centers in Washington State. Psychiatric Services 48:811-814, 1997Link, Google Scholar